Along with being cheery companions in our vegetable and flower gardens, bees are integral parts of our food systems, and our very ecosystems! Yet, these pollinators are in danger.

Bees face numerous threats across the world today including diseases and parasites, pesticides, climate change, and habitat loss.

Such challenges have led to a dramatic decline in honeybee (Apis mellifera) populations, and in 2017 the rusty patched bumblebee (Bombus affinis) was added to the endangered species list in the US.

In the UK, bumblebee populations are plummeting. On top of that, 40 percent of bees around the world are vulnerable to extinction.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

While we may feel grief-stricken for this loss of biodiversity, we should also be alarmed for our own sakes. Not only do these flying insects pollinate one third of the food we eat, they also pollinate the majority of all flowering plants.

So helping these pollinators in our gardens isn’t just a charitable action towards wildlife – it’s also a wise step towards self-preservation.

I’m not here to tell you that you can single handedly stop climate change or reverse habitat loss – I wish that were the case. But you do have within your reach something very powerful – the ability to create an oasis for these pollinators.

Whether you live on a large farm, in a tiny apartment, or somewhere in between, you can provide food and habitat for bees, and make positive changes that will benefit them – and as a result, benefit us all.

Feeling motivated? In this article you’ll learn 19 ways you can help bees.

Here’s an overview:

19 Ways to Help Bees

A bit more background knowledge of how these pollinators live their lives and what they need in terms of food and habitat – as well as the immense services they provide for us – will help us get motivated to take action and understand the importance of doing so.

So before we get started on the 19 steps we can all take, first let’s get to know these pollinators a little better!

Types of Bees

Bees are native to every continent except Antarctica, so you have probably encountered many different kinds in your lifetime without even knowing it!

The most well-known types we see in the great outdoors are honey and bumblebees, so we’ll shine a light on those two, as well as providing information to pique your interest in other types as well!

Honeybees

With fuzzy heads and thoraxes, and abdomens that are orange to gold with black stripes, honeybees are about a half an inch long.

They are taxonomical members of Apis, a genus made up of eight species, with A. mellifera being the most commonly domesticated species.

Although referred to as the “European honeybee,” A. mellifera is thought to have originated in Asia or Africa.

While this pollinator seems to be highly recognizable, in the US it is nonetheless easily confused with some native species. One way to recognize this species is that it tends to fly with its legs hanging down.

Despite what you might have heard, these aren’t the only bees that can produce honey, but they are certainly the ones most commonly used for that purpose, with over 200 thousand tons of honey sold in the US in 2021.

The reason these insects make honey is, of course, not to gratify the taste buds of humans, but to have food for themselves during winter. Most other types of bees don’t live in communities that last more than a year, so they don’t need this sweet resource.

Although honeybee queens live only one to two years, and worker bees less than a year, A. mellifera communities are perennial. These social insects live in hives with up to 80,000 members.

In the wild, these honey producers nest in cavities, such as tree hollows, while domesticated colonies are kept in wooden boxes that can be transported.

As far as bees go, hives are an exception rather than a rule. The vast majority of these pollinators don’t have this type of communal lifestyle.

However, for A. mellifera, within the hive lies the future of the colony. So when threatened by other insects, larger animals, or humans, they can become aggressive and sting.

Although honeybees are largely relied upon for pollination of industrial agricultural crops such as almonds in the US, some native species are vastly more efficient.

That’s because A. mellifera harvests nectar primarily, while native species collect more pollen.

Bumblebees

Bumblebees tend to be instantly recognizable because of their furry appearances – their bodies are covered with thick coats of hair.

These flying insects are members of the Bombus genus, which is made up of at least 250 different species, and are native to North and South America, Europe, Asia, and north Africa.

Far less aggressive than their honey producing relatives, female bumbles can sting but rarely do so.

Bumbles live in much smaller colonies than A. mellifera, with only about 50 to 400 individuals per nest.

They can place their nests in a variety of locations – including abandoned rodent holes, compost piles, in long, tangled grass, or unused bird nesting boxes.

These nests are only used for a few months, just long enough for larvae to mature.

In fall new queens born in those nests will look for a place to overwinter, being the only ones from the old nests to survive.

Queens hibernate in holes in rotting logs, under rocks, or in new nests dug into the soil.

Like some other types of bees, bumblebees buzz as they approach flowers to improve pollination. This little dance shakes the flower, allowing them to collect even more pollen.

Other Bees

The honey producers are the star of the show when it comes to bee popularity, and bumblebees are highly charismatic, looking a bit like flying teddy bears.

But there are many, many other types that deserve our interest as well!

In terms of appearance, some have yellow and black stripes, while others are a shiny, metallic green. The largest are over an inch long, while the tiniest are less than one-tenth of an inch in length.

Around the world, there are 178 different genera of bees besides Bombus and Apis, and these other types are mostly solitary – with up to 90 percent of North American species living alone.

Solitary types build their own nests, lay eggs, and collect food for their own offspring.

Sometimes these lone bees build an aggregation of nests in one area, or share the entrance to a nest, but only provide for their own offspring.

Many of these dig small nests in the ground or build nests in crevices in dead trees or logs, or lay their eggs in hollow stems.

Unlike ground-nesting yellowjackets, which are a type of wasp, ground-nesting solitary bees are not aggressive, and some are even stingless.

There are also semi-social types that share a nest and care for offspring communally, but these species are fewer in number.

The Bee Life Cycle

We usually only see these pollinators when they are flying around foraging, but to help them, we need to know that they spend most of their lives in their nests, hidden from view.

The life cycle of bees happens in four phases: egg, larva, pupa, and adult.

The adults are the ones you see flying around your garden, and for most species, this time period only lasts about two to six weeks. Compare that with the 12 months to two years of their total lives!

While there is some variation depending on the species, during their foraging time, females collect pollen and nectar, lay eggs, and these eggs grow from larvae to pupae to adults over the period of about a year.

On the other hand, males don’t collect anything to take back to the hive or nests, they are there simply to mate.

And while these pollinators go about foraging for food to feed themselves and their babies, they happen to supply a much needed service to the members of the plant world – pollination.

How Bees Pollinate

There are over 20,000 species of bees (Anthophila) in the world, and they all contribute to pollination in some way.

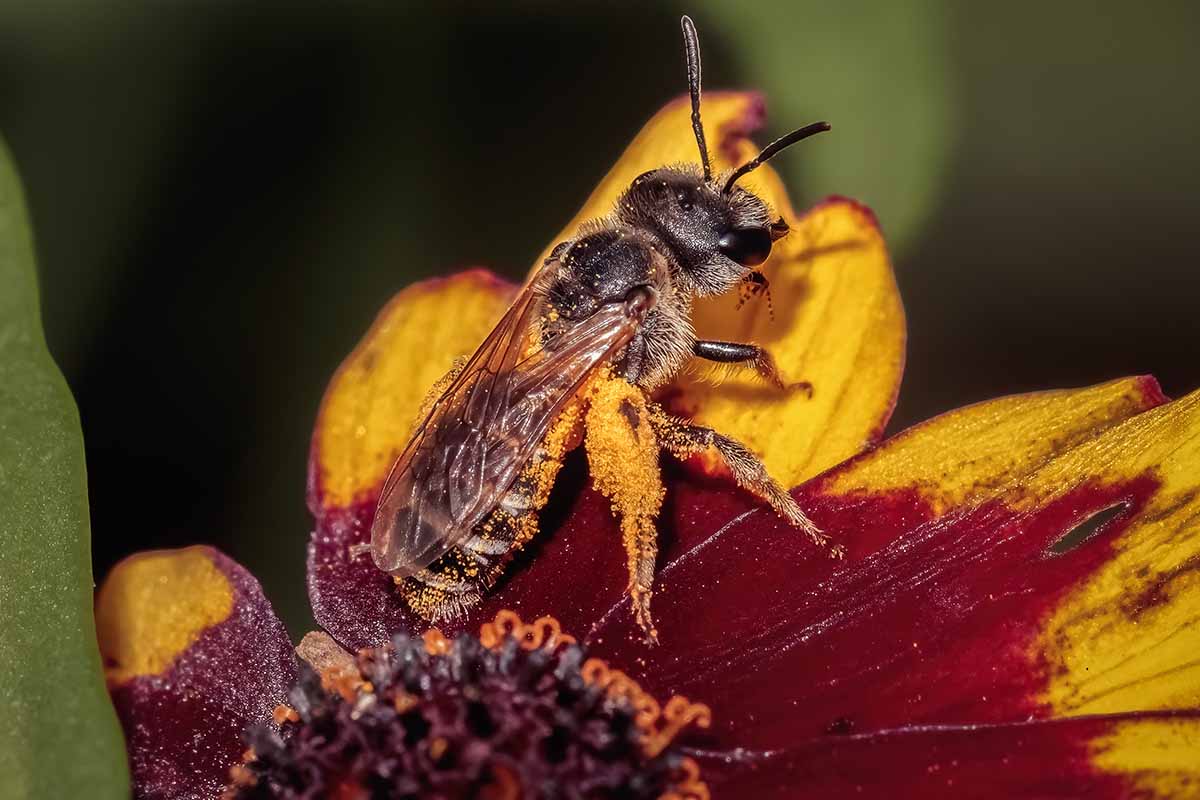

Particular features of their anatomy enable our buzzing friends to pollinate plants. The little pockets and hairs on their legs or abdomen brush against the pollen, which sticks to them as they forage from flowers.

The pollen clings to the furry parts of their bodies, and is then taken to additional flowers as the insect continues gathering food.

During this process pollen is transferred from the male part of one plant, the anther, to the female part, or stigma, of another. The stigma then produces the seeds, fruits, or nuts that we use for food.

Females don’t just transfer pollen from flower to flower – they also collect it to feed their next generation.

There are other animal pollinators including birds, moths, bats, wasps, flies, beetles, and butterflies – and other forms of pollination are utilized in nature as well. Grasses are wind pollinated, and some flowers can even self-pollinate.

But even self-pollinating flowers can benefit from a helping hand from insects – their pollination is more successful when bugs are involved.

Many of the crops you likely enjoy on a regular basis are dependent on bee pollination, including:

- Almonds

- Apples

- Asparagus

- Blueberries

- Carrots

- Cherries

And that’s just scratching the surface!

Now that you know more about how these insects live their lives, let’s get started on the 19 steps you can take to help them:

1. Avoid Pesticides

First things first. None of the following recommendations are going to do a spot of good if you use pesticides in your yard. That’s because pesticides can directly or indirectly kill pollinators, bees included.

Ever heard of colony collapse disorder (CCD)? Honeybees are affected by this disorder, in which worker bees mysteriously abandon their hive and queen.

While certainly this is terrible for these creatures, the phenomenon should make you shudder for your own well-being as well. As we’ve seen, many crops are pollinated by these insects, giving CCD far reaching economic and social implications.

Neonicotinoid type pesticides (also known as “neonics”) have been particularly implicated as being at least part of the cause of colony collapse disorder and have been banned by the European Union.

So in addition to taking an organic, pollinator-friendly approach in your garden, it’s also important to check with the nurseries where you buy your plants and ask if they are neonic-free.

If you are already practicing organic gardening, you may be familiar with organic pesticides such as neem oil.

While this product is nontoxic to humans, cats, and dogs, great care should be taken when applying it outdoors to prevent pollinators from succumbing in addition to the target pests.

Since neem oil is toxic to bees, it should only be used when the plant you want to spray is not blooming, and at night when these pollinators are not active.

Read our article about integrated pest management to learn about alternatives to using pesticides.

2. Plant in Multiples

Now that you know the most important step to protect these pollinators, let’s start considering the way bees forage.

One of the first things to keep in mind when landscaping for these insects is that life is easier for them and better for the plants they pollinate if plants are grouped together in multiples, so that the bees can gather food efficiently.

Luckily, good landscaping design generally involves choosing odd numbers of shrubs, perennials, and annuals. So when you are planning, pick three, five, or seven of one plant and group them together rather than picking just one specimen.

This is not to say you should plant a monoculture of only one type of flower.

But rather than planting one coneflower, one aster, and one milkweed in a row and then repeating the pattern, plant multiples of the same species in groups before alternating other types of plants.

Once the planting is mature, it may not be obvious how many individual specimens there are, instead there will be large swaths of color and texture which will be far more pleasing to the eye – and to these pollinators.

3. Pick Bee-Friendly Flowers

Now that you know how to make foraging more efficient for our flying, pollinating friends, if your landscaping efforts so far consist of mostly ornamental plants, there’s one thing in particular to look for that signals whether flowers are pollinator-friendly – or not.

If you want to maximize nectar and pollen forage, avoid plants that have double blooms, also known as “double flowers” or “double-flowered.”

These are flowers that have a very ruffled appearance and are the results of selective breeding and hybridization – they actually have extra petals compared to single blooms.

For instance, roses with single blooms have just four to eight petals, while some double blooms have up to 100 petals.

The problem with these flowers is that the extra petals can make it harder or even impossible for pollinators to access pollen and nectar.

Although you may enjoy certain types of flowers that are typically found with double blooms, there are single options which are just as beautiful, and much more beneficial.

In addition to roses, other plants that often have double blooms include camellias, carnations, marigolds, and peonies – so choose single types of these rather than doubles where possible.

4. Grow Perennial Flowers

While annuals will provide forage for many pollinators, a better option in the long run is to incorporate flowering perennials into your landscape.

Some annuals such as zinnias and cosmos will provide a temporary food source while perennials become established, but many annuals lack pollen and nectar and do not offer any food to pollinators at all.

Perennials on the other hand will do double duty – creating habitat as well as forage.

Unlike annuals which need to be replaced every year, perennials are grown in a designated area, so the ground isn’t disturbed as much as it is where annuals are grown.

This means that in a perennial bed a small ecosystem can become established. You’ll learn more about the importance of perennials in creating habitat later in the article, so keep reading!

Another bonus of growing perennials is that you don’t have to replace them every year like you do with annual bedding plants.

There are many different places and ways you can incorporate flowering perennials into your landscape.

If you have a farm, perhaps you could dedicate a section of pasture to becoming a meadow.

Or if you are a city dweller with no yard to speak of, you could grow perennials in pots like one native plant gardener in Los Angeles has chosen to do.

On the other hand, if you’re a suburbanite, you probably have multiple options in your yard where perennials could be grown.

Flowering perennials can be incorporated in front of foundational shrubs, at the drip line of trees, or in rain gardens. There are even flowering perennials for the shade!

Want to keep growing annuals too? Why not intersperse them into your vegetable garden where they can help provide the benefits of companion plants as well as providing additional forage?

5. Plant Flowering Trees and Shrubs

A really easy way to provide a lot of forage for pollinators is to include flowering trees and shrubs in your landscape.

Why?

Because compared to the small plants in the “perennials” section at the nursery, trees and shrubs offer a multitude of flowers, all at once – with trees being the obvious winner over shrubs in this regard thanks to their superior size.

Of course you’ll want to choose plants that are well-suited for your growing conditions and climate, but here are some ideas to get you started:

Ideal flowering shrubs for pollinators include:

- Buttonbush (Cephalanthus occidentalis)

- Meadowsweet (Spiraea alba)

- Ninebark (Physocarpus opulifolius)

- Red osier dogwood (Cornus sericea)

- Snowberry (Symporicarpos albus)

- Sumac (Rhus spp.)

- Winterberry holly (Ilex verticillata)

Smallish in stature, understory trees with great pollinator potential include:

- Hawthorns (Cratagaegus spp.)

- Redbuds (Cercis spp.)

- Serviceberries (Amelanchier spp.)

Finally, these tall, canopy trees provide good forage for bees:

- American basswood (Tilia americana)

- Black cherry (Prunus serotina)

- Catalpas (Catalpa spp.)

- Honey locust (Gleditsia triacanthos)

- Maples (Acer spp.)

- Ohio buckeye (Aesculus glabra)

Trees and shrubs that provide winter berries for birds also provide flowers for bees and other pollinators!

6. Choose a Variety of Flower Types

Now that you have a few ideas about how to provide good food sources for these important insects, the next step you can take is to make sure you have a wide variety of flower types – ones with different colors and shapes.

This is because different bees prefer different types of plants. And since these insects come in an assortment of sizes and have anatomical variations, they need a variety of flower types to forage from.

Furthermore, some are generalists while others are specialists. So a wide variety of blooms is required to feed a diverse assortment of these pollinators.

Here are some different bloom shapes and examples to get you started:

- Bell-shaped: lily of the valley, grape hyacinth

- Bowl shaped: poppies

- Cross shaped: members of the brassica family like bok choy and Virginia stock

- Funnel shaped: hibiscus

- Saucer shaped: cosmos

- Star shaped: borage

- Trumpet shaped: Carolina jessamine

- Tubular shaped: members of the mint family

- Urn shaped: blueberries

Also, it’s important to consider the shapes of inflorescences that bear many tiny individual flowers, such as umbels or spikes.

Umbel-shaped flower heads in particular make great landing pads for flying insects.

Plants with umbel-shaped inflorescences include yarrow as well as members of the carrot family like carrots, cilantro, dill, and parsley – so if any of these go to seed in your garden, leave a few for the pollinators!

7. Grow a Succession of Flowers

One way you can provide a wonderful feast for bees is to make sure that there are blooms available for as long as possible to help feed the many successive populations that emerge between spring and fall.

Here are some recommendations for plants whose flowers attract bees:

Starting in spring you can count on these for flowers:

- Beardtongue (Penstemon spp.)

- Bee balm (Monarda spp.)

- Bluebell (Hyacinthoides)

- Blueberry (Vaccinium spp.)

- Brambles

- Clover (Trifolium spp.)

- Coreopsis (Coreopsis spp.)

- Cranberry (Vaccinium)

- Crocus (Crocus spp.)

- Currant (Ribes spp.)

- Dogwood (Cornus spp.)

- Evening primrose (Oenothera spp.)

- Four o’clocks (Mirabilis spp.)

- Oregon grape (Berberis spp.)

- Prickly pear (Opuntia spp.)

- Redbud (Cercis spp.)

- Rose (Rosa spp.)

- Serviceberry (Amelanchier spp.)

- Snowberry (Symphoricarpos spp.)

- Strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa)

- Willow (Salix spp.)

Bearers of summer flowers include:

- Alliums (Allium spp.)

- Arnica (Arnica spp.)

- Black-eyed Susan (Rudbeckia hirta)

- Blanket flower (Gaillardia spp.)

- Blazing star (Liatris spp.)

- Borage (Borago spp.)

- California poppy (Eschscholzia californica)

- Catalpa (Catalpa spp.)

- Cinquefoil (Potentilla spp.)

- Cleome (Cleome spp.)

- Columbine (Aquilegia spp.)

- Coneflower (Echinacea spp.)

- Cosmos (Cosmos spp.)

- Catnip (Nepeta cataria)

- Fleabane (Erigeron spp.)

- Fireweed (Chamaenerion spp.)

- Gumweed (Grindelia spp.)

- Hyssop (Hyssopus officinalis)

- Hibiscus (Hibiscus spp.)

- Larkspur (Consolida and Delphinium spp.)

- Lupine (Lupinus spp.)

- Milkweed (Asclepias spp.)

- Russian sage (Salvia yangii)

- Sage (Salvia officinalis)

- Speedwell (Veronica spp.)

- Sweet pea (Lathryrus odoratus)

- Thyme (Thymus spp.)

Autumn bloomers include:

- Asters (Aster spp.)

- Catmint (Nepeta spp.)

- Cardinal flower (Lobelia cardinalis)

- Goldenrod (Solidago spp.)

- Ironweed (Vernonia spp.)

- Leadwort (Plumbago spp.)

- Nasturtium (Tropaeolum spp.)

- Pincushion flower (Scabiosa spp.)

- Pineapple sage (Salvia elegans)

- Rabbitbrush (Chrysothamnus Ericameria, and Lorandersonia spp.)

- Sneezeweed (Helenium spp.)

- Stonecrop (Sedum spp.)

- Sunflowers (Helianthus spp.)

- Valerian (Valeriana spp.)

- Witch hazel (Hamamelis spp.)

In some places bees are out foraging in winter, even when there is snow on the ground.

Winter bloomers include currants, hazelnut, heath, heather, hellebore, mahonia, manzanita, rosemary, snowdrops, winter honeysuckle, winter iris, and winter jasmine.

Keep in mind that some of these may bloom earlier or later, depending on your region, and some may bloom during more than one season.

8. Grow Native Species

By this point you should have a good idea of what types of blooms will provide food for your local bee populations.

But there’s one more “filter” you should apply when choosing flowering plants: whenever possible, choose species that are native to your region. By growing native species you will have a far more beneficial impact than by growing non-natives.

Want to understand why?

Having evolved together, native bees have developed long standing relationships with native plants.

And some types of bees feed only on the pollen of one plant family or genus, making them specialists. For instance, in the eastern US, approximately 25 percent of these insects are specialists.

If the plants they need aren’t around because of habitat destruction, their very existence will be at risk.

Another reason to choose natives is that non-native plants may not bloom at the right time to provide food for the species that need them.

But since you are taking steps to create a wildlife oasis, you can choose native wildflowers for flower beds or meadows, as well as native trees and shrubs.

And just because native perennials are often called “wildflowers” doesn’t mean they have to look unruly in your beds.

Learn more about growing a native wildflower landscape in our guide.

9. Leave Some Weeds

Many of us have been conditioned into thinking that everything has to be perfectly tidy at all times in our yards – we do not want weeds and wild plants sneaking through the cracks.

But this attitude can contribute to the downfall of pollinators.

Some weeds, such as dandelion, provide an important source of forage for these pollinators in early spring, especially as your wildlife-friendly native landscaping is becoming established.

That’s not to say you shouldn’t remove any weeds from your yard or garden, but before you do so, consider whether they are really problematic or not before you place them on your bad list.

Plus, some weeds are edible – dandelion can be used 15 different ways as a food or medicine, and it can also be used to make fertilizer!

10. Lose the Lawn

If you feel a strong urge to help pollinators, replacing your lawn – or even parts of it – with flowering plants is a great step to take.

Lawns are monocultures, and monocultures are not the havens of biodiversity that we are trying to create.

While many native plant enthusiasts replace their lawns with mini meadows, there are other options – such as increasing the number of flower beds, or adding additional trees and shrubs.

This article has provided you with loads of options for pollinator-friendly flowering plants, so you should have plenty of ideas by now!

11. Leave Bare Patches of Ground

Although food and habitat are tightly entangled, we’re now moving on from the food part of our pollinators’ needs and into habitat.

Let’s start at the ground level, shall we?

Ground nesting bees make up 75 percent of wild bee species – and they need access to bare patches of ground to build their nests!

If you already have bare patches of ground on your property, check them during spring and summer and you might notice mounded up soil near small holes.

Ground nesting bees prefer well-draining soils, especially those that are sandy.

If you have soil like that on your property, make sure to keep some of it bare for these insects, especially in areas close to flowers.

And if you have an area of patchy lawn where grass won’t grow, that’s perfect – just tell your neighbors it’s pollinator habitat!

12. Change the Way You Mulch

To create good habitat for bees, you may need to tweak the way you mulch.

Heavy mulch such as pine bark doesn’t do these insects any good. It’s too heavy for them to crawl under, making ground nesting impossible in those areas.

Leaf litter, on the other hand, is ideal to help encourage ground-nesting species. Bees are able to crawl under lightweight leaf litter, and the leaves will protect their nests as well.

Another change you might need to make is to avoid placing mulch right up to planted areas – instead, leave some gaps where the ground is bare for habitat.

Finally, consider grouping your plantings densely, using flowering ground covers as living mulch for even more pollinator benefits.

13. Provide Stem Stubble

If you’ve seen bee nesting boxes made up of bundled paper straws or bamboo, you might be wondering if they’re a good idea.

Here’s a better one: leave some stem stubble among your perennial plants.

Biologist and pollinator conservationist Heather Holm, author of “Bees: An Identification and Native Plant Forage Guide,” available from Pollination Press via Amazon, recommends this strategy instead of using nesting boxes.

Bees: An Identification and Native Plant Forage Guide

Holm explains that to do this, you should leave dead perennial stalks in place to overwinter, and then in spring, cut them back to about 15 inches tall.

You don’t have to leave all of the stems like this, just a few per plant. This stubble will be hidden once the perennials start growing again.

This works best with stems that are three-eighths of an inch wide or less, and will give stem-nesting bees the perfect opportunity to build their nests starting in spring.

When choosing which perennials to leave as stubble, pick plants that have hollow or pith-filled stems, such as goldenrods, asters, coneflowers, milkweed, and thistles.

Oh, and those nesting boxes?

The trouble with them is that although they are cute, by densely bundling paper straws or bamboo together, they create a buffet for predators which target Anthophila larvae. It’s safer for them if these insects’ nests are more spread out from one another.

Those boxes also require maintenance – sterilizing and switching out straws or bamboo bundles – to prevent parasite infestations.

I don’t know about you, but I don’t need one more thing in my life that needs to be cleaned! I’d rather give nature the opportunity to take care of things on its own.

Perennial stem stubble will eventually biodegrade, lasting the amount of time necessary to serve its purpose – no disinfecting required.

14. Incorporate Dead Trees

Another important nesting area for some of these insects is dead trees.

If you have a tree that needs to be taken down by an arborist, instead of cutting it down to the ground, consider leaving it about 10 feet tall where it will provide a wildlife-friendly feature.

Not crazy about that idea? How about making it horizontal instead, and incorporating a log into a natural area of your landscape?

Some types of bees like to nest in wood, so providing them with a designated stump or log feature can increase habitat and improve biodiversity.

15. Provide a Bee Bath

In addition to nesting sites, these insects also need hydration and providing a bee bath can make sure they have access to water.

However, they need access to shallow water – the water in birdbaths is too deep and they risk falling in and drowning.

You can create an insect watering hole of your own by taking a shallow dish, such as a terra cotta plant saucer, and placing some rocks or pebbles into it, then adding water.

Make sure the pebbles stick out above the water level so that the insects can use them as perching stones.

There are also premade bee baths available for purchase, such as this one from Breck’s:

Buzzie’s Bee Bath is made from resin and measures 11 inches tall by 9.75 inches wide and 9.25 inches deep. You’ll find it from the Breck’s Store via Amazon.

16. Connect Wildlife-Friendly Zones

Look around your property. Perhaps by this stage you have created several different areas that are wildlife friendly.

But are those different areas connected?

Keeping wildlife areas joined together provides more habitat and less risk to the bees when traveling from place to place.

To see if the different wildlife zones on your property are connected, you might want to sketch out a design of your landscape in a gardening journal to get a bird’s eye view.

Color in the pollinator-friendly areas in green. Are there ways you can connect the islands of green so that these insects have a safer time moving around?

Even shrubs in containers or pots full of perennials can be used to bridge the gaps between wildlife-friendly areas.

17. Meet Your Neighbors

Part of helping the bees in your own backyard might be learning to recognize them.

Sometimes it can even be tricky to tell these pollinators apart from wasps or flies, so a guide can be a great help.

Using a guide, such as “The Bees in Your Backyard” by Joseph Wilson, is an ideal way to start learning to identify the different types of bees.

And once you learn who your buzzing neighbors are, this might help inform what types of flowers you decide to add to your landscape.

You can purchase “The Bees in Your Backyard” by Joseph Wilson via Amazon.

18. Practice Citizen Science

Another way to contribute to the welfare of our insect neighbors is to get involved through citizen science.

Online communities like iNaturalist can help you recognize your resident pollinators and appreciate biodiversity.

Also, researchers can’t be everywhere all the time, so sharing your own observations might just help them!

Your observations might be used to help researchers understand if a species’ range is expanding, decreasing, or moving.

And if an important species is found in a certain area, that could provide a justification to protect that area.

Who knows – you could even discover a new species!

Learn about five of the best citizen science apps in our guide.

19. Inspire Others

With your own yard and garden as a shining example, it’s important to share your knowledge of this issue with others, and to voice your concerns.

One of the easiest ways to do this is to let others know your yard is a safe haven for pollinators.

Rustic Metal Pollinator Garden Sign

This rustic metal pollinator garden sign comes in a selection of sizes and is available for purchase from 81 Metal Art via Amazon.

Letting your neighbors know that you are caring for bees in your yard might inspire them to do the same, and at the very least will inspire important conversations!

Bee the Good in the World

You’re now equipped with 19 steps you can take to improve conditions for bees in your own front and backyard. We need our furry, buzzy friends, and they certainly need us.

How many of these steps were you already following? Have you encountered any challenges while implementing any of them?

And do you have tips of your own for creating habitats for bees and other pollinators? Tell us and other readers in the comments section below!

And if you want to keep exploring the subject of living in harmony with wildlife, you’ll love these guides too:

Funny and sad that after several years the obvious errors in this article about bees haven’t been corrected, even after people have pointed them out!

You’re the first to comment on this article. Please provide your glorious wisdom kind sage.