Corylus spp.

One of the things I was most eager for when I became a homeowner was finally having the space and time to grow my own fruit and nut trees.

I was especially excited when I learned that hazelnut trees (also known as filberts) only take three to five years until the first harvest comes in.

Hazelnuts are relatively quick and easy to grow, they don’t require as much space as other nut trees, and they produce sweet, delicious nuts each summer.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

Ready to grow your own? I bet you are!

Read on to learn the ins and outs of growing hazelnut trees.

What You’ll Learn

What Are Hazelnut Trees?

There are several different species in the Corylus genus, many of which produce the edible nuts we know as hazelnuts or filberts.

Hazels are typically categorized as members of the birch family, Betulaceae, though some botanists have further split them into a subfamily called Corylaceae.

C. avellana, the European or common hazelnut, C. maxima, often referred to as the giant filbert, and C. americana, the American filbert or hazelnut, are a few of the most commonly grown varieties.

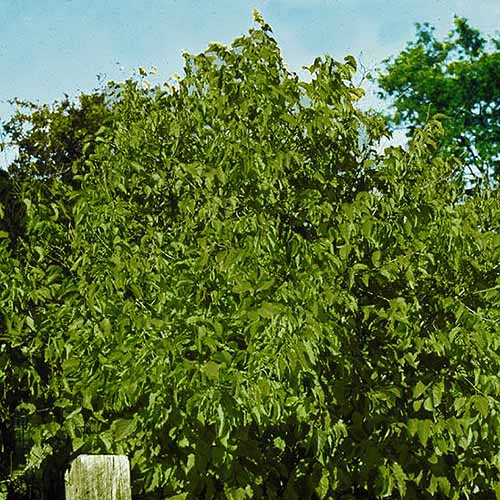

Depending on species, hazelnuts typically range from eight to 20 feet tall with a 15-foot spread, and can be grown as shrubs or small trees in USDA Hardiness Zones 4 to 9.

Since they are fairly compact and can be pruned easily, these are a great choice if you don’t have a ton of space for growing trees.

They have fuzzy, heart-shaped, serrated leaves that are a few inches in length, and produce showy yellow catkins in the early spring, followed by large nuts encased in papery husks in the late summer or fall.

Cultivation and History

Hazels are native to many parts of the Northern Hemisphere, and can be found growing wild in cool deciduous forests.

They have been a symbol of wisdom and inspiration throughout history, with written references to hazels dating back centuries.

They are mentioned in the Bible for their nutritional value and healing ability, as well as in ancient Greek and Roman mythology.

It was said that Hermes, the messenger of the Greek gods, carried a staff made from the wood of a hazel tree to provide wisdom and guide him in his travels.

Grown commercially mostly for their nuts, the wood is also used for making baskets, tool handles, fencing, and lightweight coracle boats.

Oil from the common hazel (C. avellana) is also used in food products and cosmetics.

And of course, hazelnuts are a crucial ingredient in what may be the world’s most popular chocolate spread. They are also used to make praline and chocolate truffles, and are an ingredient in Frangelico liqueur.

Propagation

Filbert trees can be propagated in a number of ways. You can start them from seed, transplant nursery stock, or grow them from runners.

From Seed

If you have lots of time and you’re not in a rush to bring in your first harvest, starting from seed can be a very economical option.

If you can find wild seeds from another hazel tree, it may even be free!

Before sowing your seeds, you can test their viability by submerging them in water. Discard any that float to the top.

Next, score the seeds to aid germination. You can do this by using a file to carefully create a small slash in the outer seed coat.

In the fall, plant the seeds in the garden 15 feet apart and two inches deep, with the slightly pointed side facing downward.

Protect them over the winter with a cold frame or a thick layer of mulch.

You can also start seeds in pots in the fall. Plant one seed an inch or two deep in an eight-inch pot filled with potting soil. Germination takes several months, so be patient!

Keep the pots outside on a covered porch, or somewhere that they won’t become waterlogged.

Once the weather warms in spring, water regularly to maintain consistent moisture, and seedlings should appear after a few weeks.

Alternatively, you can cold stratify seeds indoors by putting them into a zip-top bag filled with one part sand and one part peat moss.

Keep it in the refrigerator over the winter and then move the bag to a warm place in your house for a few days, or until you see signs of germination.

After the seeds have sprouted, plant each seedling in an eight-inch pot filled with potting soil.

Continue to grow the seedlings in the pots over the summer, keeping them in part shade, and transplant into the ground in the fall once seedlings reach eight to 10 inches in height.

From Seedlings or Transplanting

Saplings purchased as nursery stock or started from seed the previous year can be planted in the ground in late fall or winter during dormancy, to prevent heat stress and reduce the need for watering.

Space transplants 15 to 20 feet apart and plant them in holes dug to the depth of the roots and twice as wide

From Runners

You can also propagate filberts from the suckers that appear around the base of an existing shrub, or from underground runners.

During early dormancy in the late fall, dig up a sucker and the attached roots. Replant runners about 15 feet apart a foot below the soil line.

Stooling, or mound layering, is a method that involves piling soil around the base of an established shrub, leaving it in place for a year, and then dividing the new rooted stems that have developed for replanting.

This technique is common in commercial growing, though it can certainly be done in the home garden as well.

How to Grow

Find a spot in full sun, or in part shade if your climate is hot and dry.

As a rule of thumb, filberts need at least four hours of direct sunlight per day for good nut production, and about 15 to 20 feet of space to spread out, so be sure to space your plants appropriately.

Hazelnuts are monoecious, which means they produce both male and female flowers on the same tree, although they may not bloom at the same time.

While American hazelnuts can self-pollinate, European hazelnuts are self-incompatible, meaning that though a single plant has both male and female flowers, they are not able to self pollinate.

Additionally, not all varieties will cross pollinate. When selecting cultivars, it is important to plant more than one variety and pay careful attention to compatibility recommendations for pollination.

Even if planting a self-pollinating species, it is still recommended to plant more than one variety to improve yields.

To plant bare root saplings or potted shrubs purchased from a nursery, wet the roots thoroughly prior to planting, then dig a hole as deep and twice as wide as the root ball and place it in the hole.

Refill the hole, mixing in equal parts compost and sand or peat moss if working with heavy clay soil.

Tamp down as you fill in the hole to remove air pockets. The soil line should be even with the surrounding soil.

Water deeply after planting.

Once hazelnuts get going, they can really grow quickly, averaging 13 to 24 inches per year!

Soil and Climate Needs

Hazels can grow in most soil types, as long as it’s well draining. They don’t do well in boggy, waterlogged areas, and they are best planted in light soils with a pH of 5.5 to 7.5.

Soil that is too rich in nutrients will cause vegetation to flourish at the expense of the fruit.

They are adapted to USDA Hardiness Zones 4 to 9, and some varieties can even be grown in Zone 3, though springtime temperatures that dip below 15°F after the flowers bloom can lead to crop loss.

Watering Needs

While the mature trees are drought tolerant, young shrubs need constant moisture and should never be allowed to fully dry out.

Water each week during the growing season until they are well established, taking special care to water deeply during dry weather.

Aim for about an inch of water every 10 days or so for the first two seasons after planting.

Pruning and Maintenance

One nice thing about hazelnuts is they can be shaped into shrubs or trees, depending on your preference and available space.

If growing as a shrub, they don’t require much pruning, other than removing the suckers that grow out of the base of the plant in the spring.

This helps to focus the plant’s energy on the main stem.

If shaping into a tree, remove the lower and hanging branches, keeping three to five stems at the top of the main “trunk” or leader.

During the winter in the first season of growth when the plant is still dormant, select a few of the strongest, largest, most evenly-spaced branches. Prune off all other branches and cut back any other suckers at the base.

Continue to remove other new branches each year in late winter or spring for the next few seasons until the leader branch has grown to a reasonable height.

Growing Tips

- Choose two or more varieties for pollination.

- Select a location in sun or part shade with at least four hours of direct sunlight a day.

- Prune to remove suckers, or remove lower and hanging branches to shape into a tree.

Cultivars and Species to Select

There are 26 different species in the Corylus genus, as well as a number of hybrids cultivated for nut production, disease resistance, and ornamental value.

Over the years, growers have developed a number of hybrids between the C. avellana, C. maxima, and C. americana species to create varieties that have the best qualities of each, selecting for the large tasty nuts of the European types and the hardy disease resistance of the American varieties.

Corylus Avellana

The European filbert, also called the common hazel, European hazelnut, or cobnut, is a beautiful deciduous shrub often found in the wild growing on forest edges, in wooded slopes, and along stream banks.

It is easy to grow as a shrub and attractive year round, producing showy yellow catkins in early spring and large, sweet nuts in the fall.

There are a number of cultivars available:

Barcelona

This cultivar is very popular for the home gardener as well as for commercial production. It produces huge crops of rich and flavorful nuts and can be easily grown as a shrub or a tree.

‘Barcelona’ matures to 15-18 inches tall and wide, and requires cross pollination by another cultivar.

Contorta

Also known as Harry Lauder’s Walking Stick, ‘Contorta’ is an ornamental variety adored for its unique gnarled and twisting branches.

It has something to offer in all four seasons, with bold yellow catkins in early spring and attractive green leaves that turn a bright yellow in fall.

Two to four-year-old plants are available from Nature Hills Nursery.

Ennis

‘Ennis’ is a high-yielding cultivar of C. avellana that produces very large, attractive nuts with brown striped shells. It requires cross pollination with ‘Halls Giant.’

Unfortunately it is highly susceptible to Eastern filbert blight.

Hall’s Giant

While this cultivar does not produce large crops, it is the main pollinator for ‘Ennis’ as it sheds large quantities of pollen late in the season.

‘Hall’s Giant’ hails from France and is a vigorous grower, with moderate resistance to Eastern filbert blight.

York

This compact cultivar produces average sized nuts with healthy kernels. It produces a large number of catkins and releases large amounts of pollen during its flowering period.

It is resistant to Eastern filbert blight and is a great choice for a pollinator, as it is compatible with many other varieties.

You can find bare roots available at Home Depot.

Corylus Maxima

Known generally as the giant filbert, C. maxima is a closely related species to the European hazelnut.

It is similar in appearance to C. avellana, though it is typically a bit more tree-like.

Corylus Americana

The American hazelnut is a great choice for northern growers. It is tolerant to both heat and cold, and is resistant to Eastern filbert blight, which can plague the European varieties.

This fast-growing easy-care shrub produces nuts in the fall and is also useful as a windbreak.

What’s more, it adds wonderful fall color, ranging from vivid orange, yellow, and gold to deep, rich reds.

You can purchase two- to four-year-old shrubs from Nature Hills Nursery.

Managing Pests and Disease

While growing filberts is relatively easy, there are a few common issues to watch out for. Here are a few of the animals, pests, and diseases that you may encounter.

Herbivores

Hazelnuts are delicious! If you don’t want to share your nuts with forest friends, keep an eye out for critters large and small that may want in on your crop.

Deer and rabbits both enjoy munching on the leaves, branches, and catkins.

And squirrels, of course, love to eat the nuts. While it isn’t easy to keep them off your trees, it is a good idea to be vigilant and try to pick the nuts before the squirrels do!

Wire cages can also be very useful to protect young trees from hungry herbivores.

Insects

There are a number of insects that also enjoy eating hazelnuts. Keep your eye out for these common pests to reduce damage to your crop.

Filbert Worm aka Acorn Moth (Cydia latiferreana)

The adults are small reddish brown moths with a thin brown band running across the wings, and the larvae are about 1/2 inch in length with a dark brown head and a beige to pink body.

The larvae overwinter in the soil, emerging as moths in spring and laying eggs on hazelnut husks.

The young larvae that emerge then enter and feed on the developing nuts, tunneling their way through and completely destroying the kernels.

The nuts may also become infected by secondary bacterial or fungal pathogens.

Predatory insects such as parasitic wasps will eat the larvae happily.

Try incorporating lots of flowering perennials like dill, daisies, and marigolds to encourage the presence of beneficial insects and reduce pests.

Large-scale growers often use mating disruption pheromones to reduce the population of acorn moths in their orchards.

Nut Weevils (Curculio nucum)

This beetle is characterized by its elongated snout and ranges from about 1/4 to 1/2 inch in size.

The adult beetles munch on buds and leaves in the spring, damaging foliage, and lay their eggs in the developing nuts in early summer.

The larvae emerge in late summer to feed on the nuts, creating holes in the shells.

The infected nuts do not drop, and often end up being harvested along with the healthy remainder of the crop, at best creating a nuisance for harvesting, and at worst effectively ruining the crop.

One way to remove weevils naturally is to place tarps under the trees during the late summer after a rainstorm, and shake each tree until the adult weevils fall to the ground.

They will remain still for a few minutes after falling, at which point they can be collected in a bucket of soapy water and disposed of.

You can continue to repeat this method until early fall.

Disease

The diseases that tend to plague filberts are those that thrive in wet soils. You can do a lot to mitigate disease risk by planting your trees in places that are not waterlogged, with well-draining soil.

Eastern Filbert Blight

The fungus Anisogramma anomala causes cankers to form on branches and blossoms, leading to rapid wilting and dieback of foliage and branches.

This is a serious issue for the European species, C. avellana, in particular.

Cankers appear as dark, raised lumps on infected plant tissue. Remove and dispose of branches with cankers.

You can learn more about Eastern filbert blight in our guide here.

Armillaria Root Rot

Armillaria root rot is caused by the fungus Armillaria mellea, aka oak root fungus.

Leaves infected with this fungus will become discolored and drop, followed by branch die-off and the eventual death of the entire plant. Yellow mushrooms may also appear at the base of the plant.

Once this disease takes hold, plants need to be removed and disposed of. The best way to prevent armillaria is to plant resistant rootstock.

Bacterial Blight

This bacterial disease causes damage to young branches, as well as the death of buds and leaves.

Caused by the bacterium Xanthomonas campestris pv. corylina, it spreads from infected nursery stock and can overwinter in lesions on branches or trunks.

This is a particularly problematic disease in the Pacific Northwest. Remove and dispose of diseased branches.

Bacterial Canker

Bacterial canker, caused by Pseudomonas avellanae, is a particular problem in European hazelnuts.

New growth withers, and buds and leaves die, remaining attached to the tree after healthy leaves drop in the fall. Cankers can also be seen, appearing as gray areas on the bark.

Cut out and dispose of infected plant matter to prevent further spread.

Harvesting

It takes four years or so for trees to produce nuts.

When the plant is mature enough for the first harvest, the nuts will drop from the branches as they ripen in the autumn.

All you have to do is rake them into a pile or put a tarp under the tree to collect them.

See our complete guide for harvesting hazelnuts here.

Preserving

Dry the nuts by laying them on trays and putting them in a warm place out of the sun for a few weeks, turning the nuts every couple of days.

Once they are fully dry, scrape off the papery husks. You can shell them or store them in the shells.

In the shell, they will keep at room temperature for several months. Eat shelled nuts within a few weeks or refrigerate them for up to a year.

Recipes and Cooking Ideas

Whether roasted on an open fire, toasted and served atop a salad, or crushed and sprinkled over a decadent chocolate cake, having a stock of homegrown hazelnuts around the kitchen sure opens up some interesting culinary possibilities!

For a hearty hazelnut-infused dinner, try this wholesome pumpkin kamut with pecorino and hazelnuts.

Kamut is a chewy whole grain that is high in protein, and this dish resembles risotto.

Topped with some fresh grated cheese and toasted hazelnuts, this hearty meal is sure to leave you satisfied. Find the recipe on our sister site, Foodal.

If you are in the mood for a decadent treat, look no further than this mouthwatering recipe for dark chocolate hazelnut truffles.

Only four ingredients and 25 minutes are required to create an irresistible dessert that may be just too good to share. Check out the recipe, also on Foodal.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Nut tree | Maintenance: | Low |

| Native to: | Temperate northern hemisphere | Water Needs: | Moderate |

| Hardiness (USDA Zone): | 4-9 | Tolerance: | Drought (when established) |

| Season: | Fall | Soil Type: | Sandy loam |

| Exposure: | Full sun to part shade | Soil pH: | 5.5-7.5 |

| Time to Maturity: | 3-5 years | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Spacing: | 15-20 feet | Companion Planting: | Comfrey, coriander, daisy, dill, marigold, white clover |

| Planting Depth: | 1 inch (seeds), depth of rootball | Family: | Betulaceae |

| Height: | 8-20 feet | Genus: | Corylus |

| Spread: | 5-15 feet | Species: | americana, avellana, maxima |

| Common Pests: | Filbert worm and acorn moth, nut weevil | Common Diseases: | Armillaria root rot, bacterial canker, Eastern filbert blight, powdery mildew |

Go Nuts for Hazelnuts

If you are looking to grow and harvest your own nuts, in my opinion, filberts are the way to go!

Once the shrub is in the ground, you only have to wait a few seasons until you can begin filling your home with the buttery aroma of fresh roasted hazelnuts.

Are you growing hazelnut trees in your yard? Share your tips in the comments below!

And for more information about growing your own nut trees, check out these guides next:

A great article. I only have a small garden and only have room for one tree. Could I incorporate a hazel in my hedge to aid pollination? The only thing is my hedg is in the back garden and the tree will Ben in the front. Will this work and what to varieties would you recommend? Thank you Claire (UK)

Hi Claire, Glad you enjoyed the article and thanks for your question! Are you just looking for a shrub or tree that will aid in bringing pollinators to your garden? Hazels are wind pollinated and they wouldn’t be my first choice if you are mainly looking for a tree to help attract pollinators like bees and butterflies. Additionally, if you are hoping for nuts, you would need to plant two or more varieties for cross pollination. If you are looking for something to plant for attracting pollinators, I might reccomend going with a native flowering fruit tree instead. You can… Read more »

I was in the woods yesterday and couldn’t believe my eyes when I came across a hazelnut tree at least 20 feet tall. It was so healthy amidst the maples and wild cherry . At a distance of about 50 feet saplings were growing all among the hardwoods. Wonderful discovery in my part of Appalachia.

Thank you! What a helpful article. I love that you’re also in Vermont (I’m in Norwich) and are a permaculture fan! I’m looking at trying a hugelkultur thing with the four saplings I just picked up at our farmers’ market. I do want to keep them pretty short and manageable. I wonder if anyone does an espalier with them? I would love them to be a sort of fence in a few years… What do you think?

Hi Lisa,

Glad you enjoyed the article and nice to meet a neighbor! I have never seen this myself, but since hazelnuts are multi stemmed and flexible, I would imagine they could be easily formed or woven into an fence or lattice. If you try this, I would love to hear how it goes!

I planted about 50 hazelnuts as bare root plants about 2.5 years ago. They are in full sun, planted in red clay soil with some amendment. They have been lightly fertilized. about 2/3 have survived, but they have grown very little. What are the most likely causes of their failure to grow significantly?

Thanks, Joe

It is hard to say for certain why your trees are not growing well, but there are various factors that could certainly lead to stunted growth. It could be an issue with the stock you purchased. Are there other signs of distress such as discolored leaves or disease? Did the young trees get adequate water during the first couple of seasons? How compact is your soil? It is also possible that your soil has some nutrient deficiencies. Are other plants growing well there? It might be a good idea to get your soil tested to see if you have some… Read more »

Jobes Organics Fruit and Nut fertilizer will wake them up. I know they say Hazelnuts don’t need fertilizer, but one reason they say that because it causes a lot of leaf growth and hurts the nut production but mine sure liked it. If their too young to produce nuts anyway, I say use it a few times a year until they are old enough to produce nuts. Follow instructions on the bag and water them good too. Good luck Joe!!

I live in Gloucester, UK. I am sitting here watching the squirrel bury hazelnuts all over my lawn and in my plantpots. The magpie watches him and then uncovers them for himself. The squirrel knows what he’s doing and is constantly trying to chase him away. Next spring I’ll be pulling up lots of hazelnut saplings. They sprout everywhere!

Please tell me where I can buy hazelnut trees like the one in the picture in the article that looks to be about 1″-1 1/2″ trunk diameter. I live in central Ohio.

Thanks, Fred Mankins

Hi Fred,

I would start by checking your local nurseries or tree farms to see what they have available. If you can’t find one locally, you can order container or bare root hazelnut trees online from Nature Hills Nursery.

Great article!

i would love to grow hazelnuts but live in zone 9. Are there 2 dwarf varieties, under 10 ft, that will cross pollinate that I can grow in my zone?