Potting soil and the container it sits in are literally the foundation for your houseplant. Without them, your plant can’t access nutrients, doesn’t have a base of support, and won’t be able to thrive.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

It’s easy to just nab whatever pot and soil your local store has available, but if you really want to foster big, beautiful plants, you should put a little extra consideration into your choices.

You can make selections that benefit both your plant and the environment – not to mention your wallet.

If you’re ready to start with some of the most important basics of plant care, here’s what we’ll go over in this guide:

What You’ll Learn

Don’t be overwhelmed by all the various options out there. Once you have a handle on the basics, the decision isn’t so difficult. Here we go!

What Makes the Perfect Medium?

The perfect medium combines the right amount of water retention with drainage, provides support, and feeds your plant.

Which one should you choose? Every plant is different. A cactus that evolved to survive in arid, sandy soil isn’t going to thrive if you place it in a medium meant for a fern that evolved in humus-rich, moist soil.

For that reason, there is no one “perfect” planting medium.

That said, there are a few elements that most houseplants do well with. Almost every houseplant prefers soil that is loose and airy.

This kind of substrate allows oxygen to reach the roots readily. But most plants also need a medium that retains water well enough that the roots can access the water when they need it.

A good medium also provides some nutrition, which you replenish each time you fertilize, and a base of support.

The Essential Ingredients

At its most basic, potting mediums can be broken down into a few essential ingredients.

It needs to include an ingredient that helps the medium retain water, and one that improves drainage. There should be an ingredient that adds nutrition and one that creates space in the medium to allow air to move throughout.

Then, you need something that will anchor the plant and provide structure.

Often, we use ingredients that serve more than one purpose. For instance, vermiculite improves both drainage and water retention.

The following are the most common components of most commercial potting mixes:

- Coco coir: a waste product that is made out of shredded coconut husks. Provides air, drainage, and water retention.

- Compost: typically a waste product, this is broken down organic matter. Provides nutrients, some support, and water retention.

- Fertilizer: natural or synthetic products that add nutrients to the medium.

- Peat Moss: a type of moss harvested from bogs in northern latitudes. Provides air, drainage, and water retention.

- Perlite: a volcanic mineral that improves drainage.

- Shredded Bark: common in orchid mixes, a waste product from the forestry industry. Provides aeration and some support.

- Sphagnum Moss: the same species as peat moss but comes from the younger upper layer of bogs. Also provides drainage, water retention, and aeration.

- Vermiculite: a mined mineral used to improve drainage.

In addition to these materials, you’ll often see rice hulls, worm castings, sand, topsoil, kenaf fiber, volcanic rock such as akadama, grit, wood charcoal, and pumice, sold separately for creating your own potting soil or used to amend premixed potting soil.

Understanding Labeling

You might see potting soil labeled as organic, natural, or premium, and you’re probably wondering what the difference is between them. To be perfectly frank, who knows.

The issue here is that the US Department of Agriculture doesn’t regulate the labeling of garden products. So the term “organic” has nothing to do with what organic certification entails when referring to food or its production.

It could simply mean the ingredients are not inorganic – that they are carbon-based, in other words – or it could mean nothing at all. The same goes for “natural” or “premium.”

Certainly, the labeling of fertilizers in potting soil must be regulated, right? Nope.

Fertilizers might be synthetic or natural and can be composed of whatever the manufacturer decides, so they can be labeled as organic and all that means is that the components are made of organic matter.

Okay, but what about the ingredients themselves? Someone must be regulating what something like compost is composed of. Sorry, nope again. In fact, if you’re a bit squeamish, you might want to skip the next part.

Josh Harkinson at Mother Jones wrote an expose on compost, revealing that it might contain broken down sewage sludge. Do you know what is in sewage sludge besides human feces?

Motor oil, flushed medications, flame retardants, and endocrine disruptors like triclosan, to name a few. Yuck.

Since the USDA isn’t regulating things, some third-party organizations have stepped up to fill the gap.

One of the largest is the Organic Materials Review Institute. They’re a non-profit that reviews and analyzes gardening products like potting soil.

You can either visit their website or look for the “OMRI Listed” seal on packages. Then, go to their website to confirm the results of the testing if you want to avoid stuff like motor oil in your potting soil.

Being OMRI Listed means the product adheres to USDA organic farming standards, which excludes compost made of sewage, but they do allow for exceptions. That’s why you should check their website for all of the pertinent info.

Some states have their own review boards, as well. For instance, in my neck of the woods, California has the CFDA, Oregon has the ODA, and Washington state has the WSDA.

Each has its own process for certifying good practices among producers and manufacturers.

The next thing to worry about is whether something is sustainably produced, if that’s important to you. For instance, some mosses that you can find at craft and garden stores are poached out of wilderness areas like those in my home state of Oregon. This has a devastating impact on the environment.

Peat moss takes centuries to form and it is being harvested faster than it can be replaced. On top of that, peat bogs are important in the battle against climate change because they store an outsized amount of carbon dioxide.

Coconut coir is a nice alternative to peat, but it typically travels long distances before it arrives in your home, since most of it is produced in southeast Asia and some in Central America.

Lots of products contain vermiculite, but I have more bad news for you.

Beyond being a limited resource, a majority of the vermiculite mined in the US throughout most of the 20th century was contaminated with amphibole asbestos, leaving just a few uncontaminated mines in the eastern US to supply the needs of gardeners.

It’s also possible that older products sitting on gardening store shelves could include vermiculite that is contaminated with toxic asbestos.

None of this takes into account the additional concern about using products that are mined, with the cost to the environment and laborers.

If you do decide to use vermiculite, be sure that you check to see if it was sourced in the US. Testing for asbestos outside of the US isn’t always as rigorous as it is in the States.

Perlite is mined in open pits, which isn’t very good for the environment, either.

Unfortunately, if you want to know if a product is sustainably produced, you’ll have to do a lot more digging. None of the above resources analyze sustainability.

The best route is to choose suppliers that have been reviewed by third parties and to choose products with ingredients that are more sustainable.

Sustainable Options

If you’re looking for sustainable options, there are lots of new products on the market that are offering replacements for things like vermiculite and peat moss.

For instance, rice hulls, particularly if they’re produced near where you live, are a sustainable alternative to peat moss, vermiculite, and perlite.

Shredded bark offers a nice way to improve aeration, especially if you can find it sourced locally.

Many nurseries or waste management facilities sell compost that is made on-site. You can hardly get more sustainable than that – unless you decide to make a compost pile in your yard.

Compost works well as a replacement for peat on its own or in addition to other peat-replacement products.

Rotted sawdust can be used in place of vermiculite, and sand mixed with rotted leaves can replace perlite.

You can also source products from companies that are turning industrial waste products into potting soil alternatives. For instance, Organix makes a product called RePeet, which is made from waste from the cattle industry.

Fox Farm has earned a reputation for manufacturing products that contain earth-friendly ingredients, though some might have a large carbon footprint due to the amount of travel required to bring products in from across the globe.

If I could only recommend one variety of premixed potting soil, without question, it would be their Ocean Forest mix.

It is OMRI listed and contains all the perfect ingredients to make plants happy, plus they’re more sustainable than a lot of other potting mix ingredients out there.

If you’d like to try it out for yourself, pick up a 12-quart bag at Amazon.

For sustainable fertilizer, you can combine blood meal (to supply nitrogen), bone meal (for phosphorus), and kelp meal (to add potassium).

Don’t feel frustrated with trying to find the perfect sustainable, organic potting mix. Life is about compromises, so just pick the best one you can.

Choosing a Potting Mix

Before we jump into choosing a commercial potting mix, I want to point out that premixed potting mediums are a relatively recent development.

People have been creating their own mediums for centuries and you should feel empowered to do the same if it suits your situation.

That said, there’s nothing wrong with picking up a potting mix online or from the store. Many of them are carefully formulated to make your plants absolutely thrive.

The potting mix you choose will need to be selected based on the plant it will be supporting. Remember, there is no one-size-fits-all potting mix. However, there are lots of excellent options out there that will suit a wide variety of plants.

Also, don’t be afraid to think of a commercial potting mix as a starting point. Use it as a base and then amend heavily it to make it perfect for your plant. Here are the most common types that you’ll see:

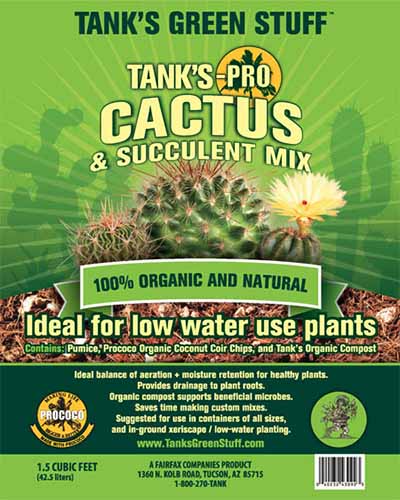

Cactus Mix

Cactus mix is made to be extremely well-draining and not very water-retentive.

It won’t have much, if any, organic matter. Ingredients usually include sand, lava rock, perlite, pumice, grit, and gravel. It’s best for plants that need little water and have shallow roots.

Cactus potting soils are ideal for succulents, cacti, and even Mediterranean herbs like oregano, sage, and thyme. It’s also an excellent choice for starting most seeds.

If you work in some compost and peat (or a peat alternative), it’s also good for many epiphytes like hoyas and peperomias.

Tank’s-Pro Cactus & Succulent Mix

Grab a 1.5 cubic foot bag of Tank’s Pro Cactus & Succulent mix at Arbico Organics.

Orchid Mix

Orchid mixes are made to allow tons of air to circulate around the roots of your plant.

They usually include lots of chunky materials such as bark, moss, and coco coir. In addition to using it to pot orchids, it’s an excellent medium for growing most types of epiphytes.

Miracle-Gro Orchid Potting Mix

Walmart carries eight-quart bags of Miracle-Gro Orchid Potting Mix.

Standard Mix

Standard potting mixes are made to accommodate most houseplants. They usually combine compost, perlite, vermiculite, and moss.

These mixes work for just about any type of plant except cacti and succulents. However, I almost always amend mine a little to suit the specific plant that I’m working with.

Every species has unique needs, so you’ll need to do some research to determine exactly what will suit yours the best.

But broadly, I like to mix in lots of bark and rice hulls, along with some worm castings, for any variety of epiphyte except orchids.

That means pothos, hoyas, monsteras, ficus species, and philodendrons. Typically, I mix two parts bark, two parts potting soil, and one part rice hulls with just a dash of worm castings.

For ferns, calatheas, and alocasias, I add two parts compost to two parts potting soil, a dash of worm castings, and one part moss. I just use the stuff that’s growing on the trees in my yard to keep it ultra-sustainable, but you can buy non-peat moss as well.

The Right Container Material

I wish there was just one perfect container material out there and we could all just use that for our houseplants and not have to worry about anything else, but that’s not the case.

Rather, the opposite is true. All container materials have their uses, and selecting the best one is largely a matter of preference.

The typical materials that you’ll see are concrete, plastic, terra cotta, ceramic, metal, wood, and fiberglass. The following provides an overview of each of these.

Terra Cotta and Ceramic

Terra cotta and ceramic are related in that they’re both made of fired clay. Terra cotta is rarely glazed, while ceramic pots often are.

Both can be extremely heavy when they are large, and both break easily if you drop or mishandle them. Terra cotta also tends to dry out faster than glazed clay or plastic.

On the plus side, they’re usually more affordable than other types of pots, come in a range of colors and sizes, and can last an extremely long time.

Plastic

Plastic pots run the gamut from the cheap, flimsy pots growers use to start plants in, to higher quality, more substantial options.

They are generally worse for the environment than other types, unless you source pots made with recycled plastic.

Remember, plastic takes a long time to break down in the environment. Plus, lower-quality pots tend to crack after just a few years, especially if they’re displayed in bright sun.

There’s also a chance that some plastics can leach chemicals into the soil, which is bad if you plan to eat your plant.

The positive of using plastic is that it’s generally quite affordable, containers are lightweight, and they come in a massive range of colors and sizes.

Concrete

Concrete pots are more popular for outdoor plants, but they work well indoors, too – especially if you have a large tree, since they provide an anchor so your plant won’t be knocked over by the overly-enthusiastic dogs that are playing keep away in your house. Or is that just me?

The downside to concrete is that it’s heavy! Definitely a set it and forget it situation, if you use one of these. The upside is that they’re durable and long-lasting.

Fiberglass

Fiberglass containers are the chameleons of the pot world. They can be made to resemble concrete, terra cotta, plastic, or ceramic.

While they can break down in direct sunlight, and they can be pricey, they’re lightweight, durable, and stylish.

Metal

Metal can be painted, sealed, or left natural. You can buy new metal containers or repurpose old buckets or bowls.

These tend to allow for a greater fluctuation in temperature than other types. They break down over time, but they’re usually lightweight and affordable.

Wood

I wish wood containers got more love. They combine the insulating properties of terra cotta with the longevity of concrete (when cared for properly).

With a weight somewhere between that of concrete and plastic, the cost is generally moderate.

You can also make your own or buy ones made out of recycled wood, which is great for the environment. The downside is that you need to maintain them. Use a liner or seal them regularly to extend their lives.

Size Options

I regularly encounter people who are shocked to learn that some plants do better if they’re a bit root bound.

Monsteras, hoyas, philodendrons, pothos, fiddle-leaf figs, and orchids (any epiphyte, really) are all much happier if the container that they are in isn’t much larger than the root ball itself.

Why? Because it’s easier to water the root ball without providing too much excess moisture.

What happens when you have a ton of soil around a root ball is that you have to add a lot of water to moisten everything.

Then, that excess moisture that isn’t being used sits there and restricts the amount of oxygen reaching the roots. If there isn’t too much soil, on the other hand, it’s easy to provide moisture just to the soil near the roots.

That’s why you need to research the individual species that you’re working with when choosing a pot size. You can often just use a similar size to whatever the plant came in to start, but knowing what it prefers is going to make all the difference.

Many plants that like constantly wet soil, such as most ferns, are fine in larger containers.

You should also consider the shape of the root ball. A plant with a shallow and wide root system does better in a shallow pot than one with a long taproot.

For instance, you can grow an arrowhead plant in a dish garden, but a lithos needs something deep and narrow.

In general, aim for a pot that is a few inches larger in diameter than the root ball and about the same shape. There’s no point in feeding and watering a bunch of soil that your plant’s root system isn’t going to be able to use.

Drainage

There are two types of pots out there: those with drainage, and the wrong ones.

All joking aside, don’t ever, ever, ever use a decorative pot without drainage holes to grow your houseplants. I know it’s super tempting since these cachepots are often the most decorative options you’ll see.

You can use these pots if you keep the plant inside in a separate pot with drainage holes. Then, every time you water, remove the plant and dump the excess water after about 20 minutes.

With pots that have drainage holes, be sure to empty the catchment container after about 20 minutes, as well.

Now that I’ve completely scared you away from using pots without drainage holes, I’m going to level with you. Experienced growers can use these types of containers.

Once you have a feel for when and how to water a plant, you can use pots without drainage holes for many species of houseplants. It requires extra diligence and extreme care, but it’s possible.

If you feel confident enough to go this route, consider placing a layer of activated charcoal in the base of the container.

Charcoal absorbs excess water, so if you happen to overwater (and we all do it) the charcoal will help mitigate the damage.

Give Your Plants the Right Base

They don’t call it a foundation for nothing. The right container and potting substrate provides the literal base of support for your plant, as well as giving it the right elements to grow big and healthy.

Do you have a premixed potting soil that you’re a big fan of, or a homemade mix that you like to use? If so, share it with us in the comments!

Now that you have your foundation in place, you might be interested in learning how to grow a few houseplants. Here are some excellent options to start with: