If asked to picture a houseplant, what comes to mind first is likely a specimen potted up in a pretty container filled with soil.

But there is an entirely different category of houseplants available to you that can be grown on driftwood, shells, lava rocks, and pieces of wood.

These plants are called epiphytes, and they grow on other plants in the wild, usually trees.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

You probably don’t have a massive tree growing inside your house, but that’s okay!

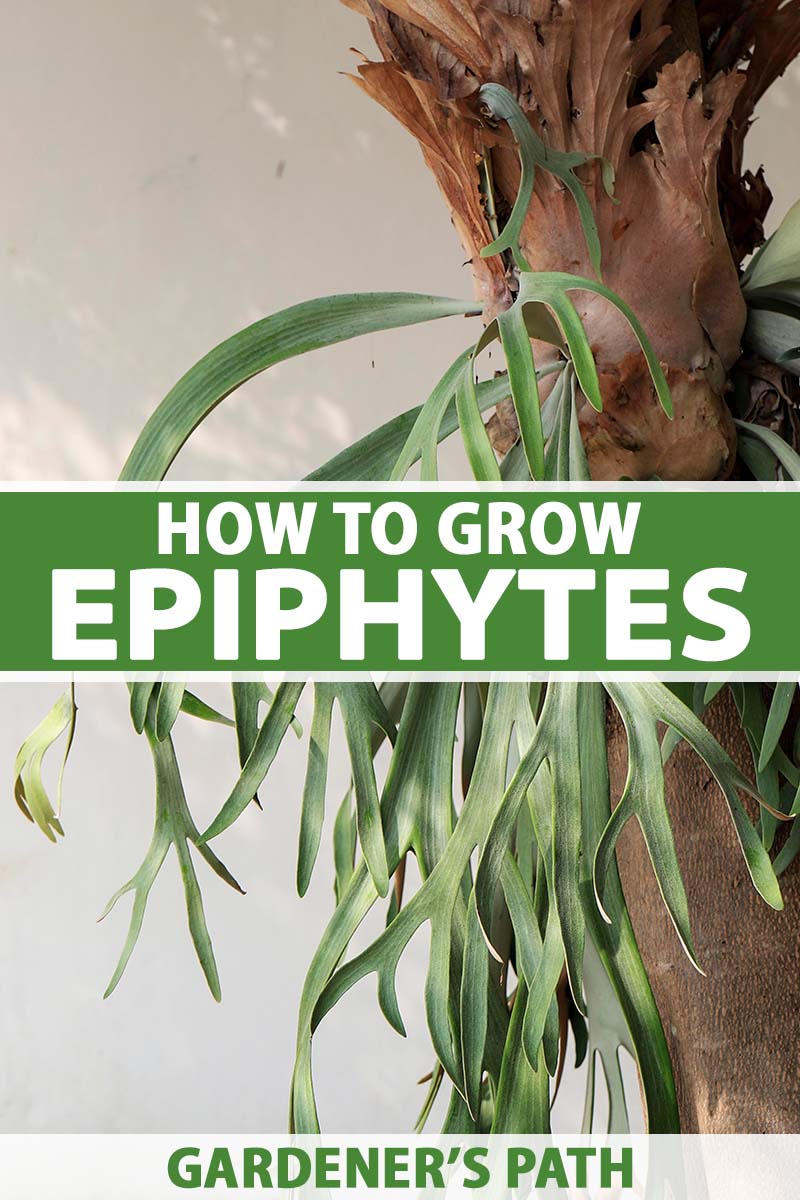

Imagine a staghorn fern mounted on a wood plaque or an orchid growing in the crook of a pretty piece of driftwood that you found on the beach.

In this guide, we’ll introduce you to the wide, wonderful world of epiphytic plants. Here’s a quick rundown of what’s coming up:

What You’ll Learn

Whether you’ve already brought home an epiphyte and want to know how to care for it, or you’re just curious about these fascinating plants, this guide has you covered.

Let’s dip our toes into the water.

What Are Epiphytes?

Epiphytes are defined as plants that grow on other plants, and they make up an astounding array of different species. For instance, Spanish moss is an epiphyte, and so are Swiss cheese plants and fiddle-leaf figs.

Mosses, orchids, bromeliads, and certain types of ferns are some of the most common ones, but epiphytes are found in every major plant family.

Most epiphyte seeds are spread by birds and mammals such as monkeys that eat the seeds of mature plants or the fruit that contains them. They drop the seeds, or the seeds come out in their waste, and often these will land on the branch of a tree.

Most likely to germinate if the seed lands in a crook of a branch where mosses or lichens have gathered, they can make a home anywhere that moss, lichens, or plant waste is found along the branches or trunk of a tree.

Then, the seed germinates and sends roots out to grasp onto the tree and hold the plant in place.

Epiphytes aren’t parasitic, meaning they don’t draw nourishment from the host plant. They are plants that can get everything they need to survive – sun, air, water, and nutrition – on their own. They simply use another plant as a means of support.

If you think about it, growing in the air in a tree has some advantages. You’re close to the animals that spread your seeds, and you’re closer to the sun and rain. You’re also out of reach of grazing species and other earth-bound animals.

Some epiphytes spend their whole lives up in the air, while others send roots down as they age. These roots eventually reach the soil, where the plant continues to grow.

Still others start in the ground and climb up trees or shrubs. The first, entirely airborne group are called holo-epiphytes, while the latter two are called hemi-epiphytes.

By the way, there are epiphytes that grow on other living organisms besides plants as well. These are called epizoic. Algae and barnacles are two examples. They both grow on sea mammals, while algae also grows on sloths.

You might take a look at this list and wonder why so many of these are frequently being grown as potted houseplants if they grow in the branches of trees in the wild.

Hemi-epiphytes are perfectly happy in well-draining, light soil, but even holo-epiphytes can be coaxed into living in a potting medium, for the most part.

Plants are wonderful lifeforms, adapting to a range of conditions to survive. You can also grow many types without soil as houseplants, if you want. It’s a bit more of a challenge, but the results can be pretty exceptional.

If you’re interested in learning to grow these plants without a soil substrate, this guide includes some recommended species to try – so keep reading!

How to Grow Epiphytes

There are numerous ways to grow epiphytes without soil, but every species is different, so you need to be sure to understand the specific requirements of your selected variety before you jump in with both feet.

That said, there are some general guidelines that you can follow for most species.

First, you must choose a supportive base for the plant to replace the tree or other plant that they would normally grow on.

Options include growing in a container filled with bark or lava rock (think hanging baskets or small bowls), securing the plant to deadwood or cork, or anchoring it to a sphagnum moss-covered object.

Most species need a soilless medium such as moss or coconut coir to hold moisture, but there are a few that can grow without it.

Don’t use peat moss unless you’re growing a species that prefers acidic conditions. Instead, you can choose sphagnum moss which has a neutral pH.

Additionally, try to buy your sphagnum moss from a reliable source. Many mosses and lichens are illegally harvested from the wild, which is detrimental to the environment.

It’s worth noting that sphagnum moss and peat moss technically come from the same plant, but the former is the live part that grows on the soil, while the latter is decades – or even centuries – worth of dead sphagnum moss that has compacted into layers.

That’s why peat moss isn’t a very sustainable option, while harvesting sphagnum moss is a bit friendlier to the planet.

Coconut coir is a suitable alternative since it is made out of waste from the coconut growing industry, and it has a more neutral pH than peat.

Make sure to purchase a coconut coir that has been processed to remove salts and chemicals, and is formulated for use as a growing medium. While you can use chips or fiber, compressed chips and pith are easiest to work with.

Prococo Compressed Coconut Husks

You can purchase 10 pounds of compressed chips from Arbico Organics if you’d like to use this medium in your growing endeavors.

Remember that most epiphytes don’t grow on bare wood in nature. The seeds usually land in moss or debris that has gathered in the crooks of tree branches, and that’s where they grow.

Most of the plants on the following list need some sort of medium to grow in.

If you use driftwood, which makes a beautiful base, it requires a little preparation. Also, be sure to check for any local restrictions on gathering driftwood in your area.

Soak the wood for 24 hours to leach out any salts that it may contain or be coated with. Rinse the wood well, and allow it to dry.

Next, you need to be selective about the specific specimen you choose.

When selecting a specimen to mount, find one that has a small crown of foliage, with a large stem, if possible.

You don’t want to choose something that is top-heavy because the roots won’t be able to support the weight, and the plant won’t stay put. You want something that can develop a solid root structure before producing lots of large foliage.

In the wild, epiphytes germinate in the spot where they will ultimately develop and grow. That gives them time to attach to the tree before they send out a big, bushy crown of foliage. But we are working with plants that have already germinated and grown a bit for indoor cultivation, so you will need to provide a little assistance.

Any epiphyte you transplant that shifts around at all, say in a breeze or because it is bumped, won’t be able to develop a secure base.

That’s why we need to mount them using some sort of anchor, to prevent damage to the developing root system. This anchor can be removed once the root base is sturdy.

Suitable anchor materials include jute, twine, fishing line, silicone glue, bonsai wire, or rope.

Before you anchor the plant, you’ll need to either wrap the roots in sphagnum moss (or your chosen material) or attach your substrate material securely to the base. You can use staples, glue, or fishing wire to do this.

Attach the plant by the stem to the base using your chosen material. Don’t attach it using the foliage.

If you want to cover up any obvious twine or wire, use a pH neutral glue to hold a thin layer of moss in place on top of the anchoring material.

I use an acid-free glue made for bookbinding by Lineco, available at Amazon in 16 ounce bottles.

For those grown on a vertical support base, if the plant won’t stay in place even after you’ve attached it with your anchor, remove some leaves or choose a smaller plant. You want to allow the plant to develop a large root system before it develops a large crown.

Most epiphytes can be watered by misting them or saturating the growing base.

Almost all epiphytes grow in warm, tropical areas in the wild, so they need a warm environment. That’s why you usually see them growing indoors. And most need bright, indirect light.

Epiphytes need to be fed using a foliar fertilizer. You can use any liquid houseplant fertilizer for this. Dilute it by half and pour it into a pressure sprayer, then gently mist your plant. Timing and frequency varies depending on the species.

Pressure sprayers are handy for more than just fertilizing. You can also use them to mist the plants to increase humidity. Fill the bottle with water, pump it a few times, and then hold down the trigger to spray.

Delta Plant Care Pressure Sprayer

If you plan to grow epiphytes, it’s a good idea to keep one of these on hand! Arbico Organics carries a 48-ounce sprayer that’s perfect for home use.

Or, if you are looking or something a bit more decorative, Terrain carries gorgeous copper plant misters that provide a gentle spray of water for your plants.

15 Varieties that Shine as Houseplants

If you come across a species at a garden center or online that is an epiphyte, even if it is growing in soil currently, you can transplant it to grow on wood or in a hanging basket if you choose.

Here are 15 varieties that are commonly found in stores, and that will grow well this way.

1. Anthurium

Most, but not all, Anthurium species are epiphytes. The popular A. andraeanum species is epiphytic and can be grown this way in the home.

You will often see these pretty plants around the winter holidays, and the red spathes and deep green foliage of some species complement a holiday color scheme perfectly.

Most species grown as houseplants reach about 18 inches tall.

Those beautiful, glossy spathes have spadices at the center that form reproductive seeds if the tiny flowers that cover them on the outside are pollinated. In the wild, these seeds are eaten by birds and spread from one tree to the next.

To grow one of your own, remove the plant from the soil it came in and wrap the roots in sphagnum moss or shredded coconut coir. Tie everything together with jute, and affix it to your chosen support.

By the way, if you’re interested in grabbing a gorgeous A. andraeanum with bright red spathes, Nature Hills Nursery carries plants in four-inch containers.

Anthuriums can be grown outdoors in USDA Hardiness Zones 10 to 12. Indoors or out, provide them with bright, indirect light.

Read more about how to grow anthurium houseplants in our guide.

2. Begonia

Not all begonias are epiphytic, but many are. B. abdullahpieei, B. ampla, B. blancii, B. conchifolia, B. fusicarpa, B. fulvo-setulosa, B. herbacea, B. lanceolata, B. prismatocarpa, B. rex, B. scutifolia, sect. trachelocarpus, and B. velloziana are a few examples of epiphytic species.

These plants need lots of water, and they must be kept moist. They’re not for the lazy houseplant parent.

That’s why many people choose to grow them in terrariums, and misting is also welcome. They like the surrounding conditions to be extremely humid.

Try to keep these plants somewhere that they won’t be exposed to extreme changes in temperature, breezes, or drafts. You don’t want to place yours near a door or air vent. They like bright, filtered light but not direct sun.

In other words, these species aren’t the best for beginners. But if you can anchor a beautiful begonia, it makes quite a statement.

They can be grown outside on Zones 9 and 10, but extra diligence is required to keep them moist if you don’t live in an area that is naturally humid.

If you’re up for the challenge of starting your begonia from a leaf cutting, you can find fresh B. blancii cuttings available via Amazon.

This is an exceptionally good species to grow as an epiphyte and its mottled leaves look striking in a terrarium.

3. Bird’s-Nest Fern

These popular houseplants (Asplenium nidus) are commonly grown in pots, but in their native habitat, you’ll find them high up in the crooks of trees.

These ferns have long, medium green, spoon-shaped leaves that grow up to two feet long.

To succeed at growing this species without soil, you need to keep it in a humid environment. A daily spritz can do the job, but its odds of thriving are even better if you provide a base of sphagnum moss to hold some moisture.

You can grow them outside in Zones 10 and 11, and indoors otherwise.

Provide your bird’s-nest fern with partial shade and a location out of direct sunlight. Filtered or dappled light is best.

You can find bird’s-nest ferns in four-inch growers pots available from Home Depot.

4. Blue Star Fern

You won’t see these plants (Phlebodium aureum) too often in your average nursery, but they’re worth seeking out. The matte, dusty, blue-green foliage somewhat resembles fingers.

This plant can grow in low light, or bright, indirect light equally well.

Blue star ferns need a moss base to do well, but their lightweight foliage means they can be anchored to a fairly petite base. They are hardy in Zones 9 to 11.

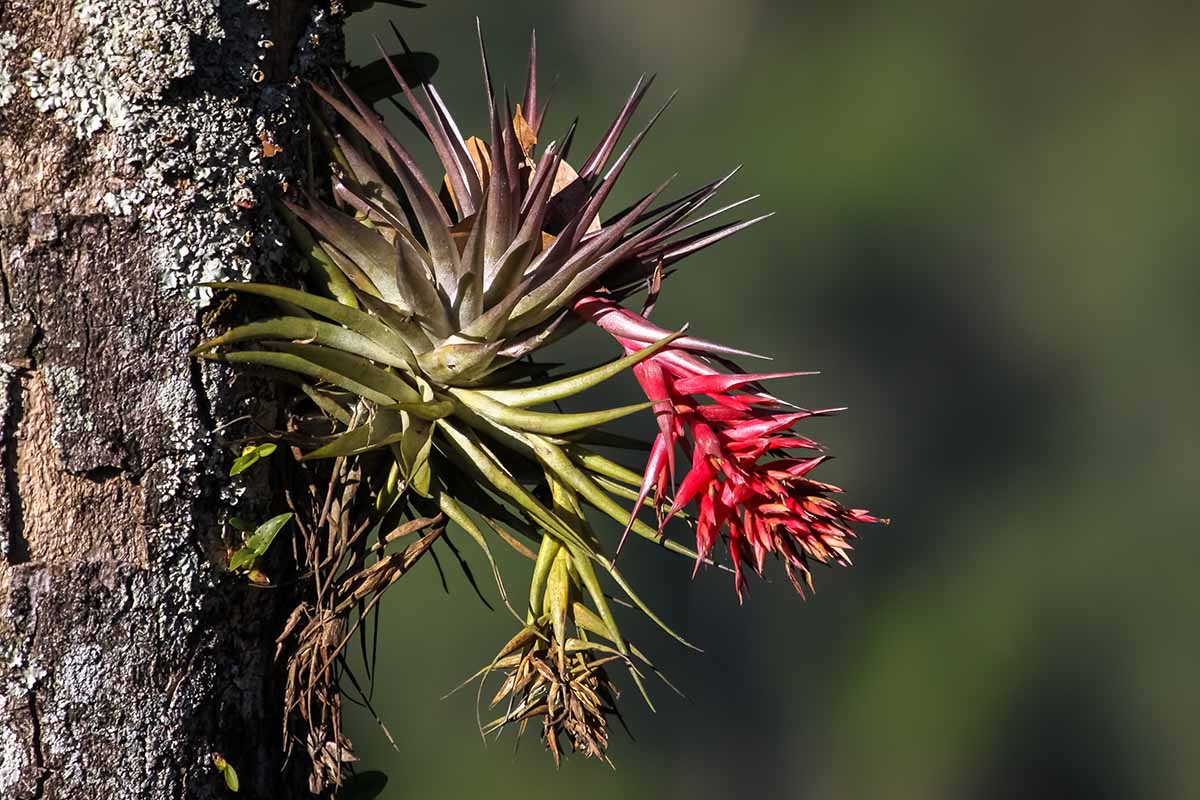

5. Bromeliad

Plants commonly known as bromeliads are members of the Bromeliaceae family, and feature striking leaves and sepals that come in a range of colors, including red, green, purple, yellow, and orange.

They can be solid, or feature stripes or spots. Not all bromeliads are epiphytes, but many are, including species in the Aechmea, Billbergia, Cryptanthus, and Vriesea genera.

They require a substrate to hold onto, whether that’s bark, cork, deadwood, or sphagnum moss. A little humidity will be appreciated, and bromeliads prefer an acidic substrate, so peat moss works well.

Most gardeners grow them indoors, but you can also grow them outdoors in Zones 10 and 11.

These plants will pup and spread along whatever support you put them on, so you might opt to use a long piece of driftwood that your bromeliad can expand across.

Bromeliads have varying light needs, but most epiphytic types prefer shade or filtered partial sunlight.

6. Dischidia

All plants in the Dischidia genus are epiphytes. You’ll most often see million hearts plants (D. ruscifolia), watermelon (D. ovata), and ant plants (D. pectinoides) in stores.

These plants are fairly petite, so they don’t need massive supports. Anchor them on small pieces of wood covered with sphagnum moss and let them trail down. It’s like having a living piece of wall art.

In Zones 10 to 11, you can let them trail off tree branches or decorative wood outdoors.

These need frequent misting and bright, indirect light to stay healthy.

7. Epiphyllum

Epiphyllum is a genus of cacti and these species are popular houseplants. As you may have guessed from the name, they are all epiphytes.

E. anguliger, E. hookerii, E. oxypetalum, E. pumilum, E. x ‘Edna Bellamy’ are some of the common species you’ll find at stores.

Despite being cacti, they need a generous amount of water. You can’t let the roots dry out if you want them to thrive.

For that reason, they do best in a basket or other bowl-like structure filled with peat or sphagnum moss, or coconut coir. Provide bright, indirect light and regular misting. Raised in the right conditions, they’ll treat you to a show of flowers during the winter.

You can grow these outdoors in Zones 10 and 11, and they may form their delicious fruits if you do.

Find more tips on growing Epiphyllum or orchard cacti here.

8. Fern Leaf Cactus

The fern leaf cactus, aka fern leaf orchid cactus (Selenicereus chrysocardium) has dramatic, wing-like “leaves,” which are actually stems.

These are fast-growing and undemanding when it comes to water. The foliage is glossy, medium green, and gracefully weeping. This species is a shy bloomer, so don’t expect to see any of the spider-like yellow and white flowers if you’re growing it indoors.

This plant needs a large base of support since it can grow fairly large and heavy. But it doesn’t need frequent watering or any misting.

You can grow it in rocks, sphagnum or peat moss, or bark, either indoors, or outdoors in Zones 10 and 11. This species also needs bright but filtered light.

9. Fiddle-Leaf Fig

Yep, those Jurassic-looking plants commonly referred to as fiddle-leaf figs (Ficus lyrata) that you see all over the place in homes and hotels are actually epiphytes. Hemi-epiphytes, to be exact.

Birds and mammals eat the seeds of the fig fruits and spread them to other trees. As the plant grows, it sends down roots that wrap around the host tree, earning all plants in the genus the nickname strangler fig.

Eventually, the roots reach and anchor into the soil, and the host plant is smothered to death. At that point, the fiddle-leaf fig grows as a terrestrial plant with those giant aerial roots forming the trunk.

The only reliable options to grow this plant as an epiphyte at home are to purchase a very young seedling and anchor it as described above, or to take a cutting and root it in moss on a large support.

You can grow it either of these ways for a few years, but eventually, you will have to transplant your plant into some soil because it will become too large to be supported by the base you provided.

Remember, in nature, these plants will eventually send down roots into the earth to act as an additional support, but they likely won’t have that opportunity in your home.

You could place a pot filled with soil below the plant for it to send roots down into, if you’d like. Eventually, the aerial roots will anchor into the soil and form a sort of trunk.

Even indoors, these plants will eventually grow too large to stay supported in the air. But in the meantime, they make astounding aerial specimens.

Outdoors, in Zones 9 to 11, you can allow the plant to send down aerial roots to the soil on its own and it will stay supported this way. Those roots are strong enough to essentially act as a trunk for the canopy.

Provide it with bright, indirect light or a few hours of direct morning sun.

Don’t have a fiddle-leaf fig that you can take a cutting from?

You can purchase a two-foot-tall plant from Costa Farms via Amazon. Just be sure to trim off a few leaves before anchoring it to your chosen base so it isn’t too top heavy.

Learn more about growing fiddle leaf figs in our comprehensive guide.

10. Hoya

Hoyas are pretty outstanding houseplants because they are so diverse, but most are extremely easy to care for, needing indirect light and moderate water.

Most species produce lovely blossoms, and most are also epiphytes. You can read more about recommended varieties to grow at home in our roundup.

They do well when grown in bark or moss – either sphagnum or peat, depending on the species – and have hanging or upright growth habits, so you can choose the right one to meet your design goals. You can sometimes find them in stores pre-mounted onto planks of wood covered in sphagnum moss.

Hoyas are hardy outdoors in Zones 9 to 11.

Check out our guide to growing hoyas to learn helpful tips for home cultivation.

11. Lipstick Plant

Aeschynanthus radicans is quite happy in sphagnum moss and grows well under artificial light, so it’s an ideal option for apartment dwellers or offices.

Thanks to their weeping habit, lipstick plants are also suitable for growing in hanging baskets filled with moss. But they need a lot of water, so don’t skimp.

To encourage blooming, reduce watering in the winter and expose them to temperatures in the low 60s. This species may be grown outdoors in Zones 10 and 11.

12. Monstera

Monstera species such as M. adansonii, M. deliciosa, and M. pinnatipartita are hemi-epiphytes. Though rare, they may send aerial roots down into the soil and eventually finish their lives as terrestrial or semi-epiphytic plants.

More often, they can start growing in the soil and climb up other plants, using aerial roots to find that marvelous sunshine, and eventually leaving the soil. Quite adaptable, Monsteras!

You’ve probably noticed that Monsteras can grow to be extremely large. That should tell you that you can’t anchor these plants to something petite like a hanging basket or shell. Look to tillandsia if that’s your dream – we cover these plants in more detail below.

You’ll need a large piece of wood covered in lots of moss, and even then, you’ll probably need to move your Monstera to some soil eventually.

I’ve grown mine on driftwood and deadwood covered in an inch-thick layer of moss and lichen that I gathered from my trees. I anchored the wood vertically in a pot of soil. After about a year, the plants sent roots down into the soil. At that point, I left the wood in place to act as something for the plants to crawl up.

It’s very difficult to grow these as hemi-epiphytes for their entire lives unless you do it outdoors, which is possible in Zones 10 to 12.

Otherwise, treat the hemi-epiphytic species as you would any other Swiss cheese plant. Our guide provides plenty of information for keeping these beauties happy.

Head over to Nature Hills Nursery to add M. deliciosa in a six-inch pot to your collection. That should be just the right size to start growing your new plant aerially.

13. Orchid

A large majority of orchids are epiphytes, with about 70 percent of species growing on other plants. These orchids have a smaller root structure than those that grow in the ground naturally.

Species in the Cattleya, Coelogyne, Dendrophylax, Epidendrum, Ionopsis, Oncidium, Phalaenopsis, and Prosthechea genera are some of the most common epiphytic varieties.

If you pick up an orchid at the store and it is growing in a basket filled with moss or bark, you can be sure that it’s an epiphyte. If your orchid is currently in flower when you buy it – and it likely is – wait until it has finished blooming before you repot or mount it.

Orchids come in a wide range of hardiness levels, sizes, and colors. You can find types that will grow outdoors year-round in Zones 6 to 12.

They must be kept moist and benefit from daily misting. Their light needs vary.

Though most orchid-lovers are in it for the flowers, Home Depot carries Phalaenopsis orchids that aren’t in bloom in five-inch plastic pots, so you can avoid wasting money on the kind that are sold in fancy containers.

These are perfect for our needs, because you want to mount your orchid while it isn’t blooming.

14. Orchid Cactus

Disocactus ackermannii has a beautiful weeping habit with thick, succulent leaves and bright red flowers.

Orchid cacti aren’t demanding about water, which makes them a nice option for those who live in drier areas. They grow well outdoors in Zones 10 and 11, but are just as happy indoors with bright, indirect light.

Because they produce big flowers and heavy foliage, they need a large, sturdy anchor. Acceptable mediums include rocks, bark, and moss. Grow this species in filtered sunlight.

15. Peperomia

Peperomias are beloved houseplants for good reason. They are easy to care for, don’t need much sun or water, and provide year-round textural color.

Many species also happen to be epiphytes, including P. albovittata, P. angulata, P. argyreia, P. caperata, P. emarginela, P. obtusifolia, P. pellucida, P. prostrata, P. rotundifolia, P. serpens, and P. tetragona.

While they like a little bit of misting, they don’t need a ton of water around their roots. A moss base anchored to a small support is all you need, since these plants are fairly lightweight.

Most species can survive outdoors in Zones 10 and 11.

Amazon carries watermelon peperomias in four-inch containers, which is just the right size for starting them as epiphytes.

16. Philodendron

Philodendrons are extremely similar to their relatives Monsteras in appearance. In fact, they are often confused for each other and were once classified together.

These, too, generally start life in the ground and send up aerial roots to climb up host plants. Once they climb up the plant and reach sunshine, the stem in the soil dies and they become completely epiphytic.

Extremely adaptable, philodendrons will slowly climb through the treetops, allowing the shadier bits left behind to die. If the spot they are growing in is too dry, they’ll just send roots down into the ground to find water.

Even more impressive, if part of the plant falls to the ground in a windstorm or other disaster, it can start all over again. Many hemi-epiphytes can’t do this.

If you want to try growing a philodendron without soil, you’ll still need a sturdy base covered in moss that’s anchored in soil for the plant to drop roots into if needed.

They’re similar to fiddle-leaf figs or Monsteras in that way. You can also let them do their thing naturally outdoors in Zones 9 to 11.

If you’d like to try your hand at growing one, Home Depot carries beautiful heartleaf philodendrons in six-inch nursery pots.

Learn more about how to grow philodendrons in our guide.

17. Schlumbergera

Christmas cactus (Schlumbergera x buckleyi), Easter cactus (S. gaertneri), and Thanksgiving cactus (S. truncata) are popular options for adding color to the home during the cooler months when they are in bloom.

When grown without soil, they need a substantial base to cling to, like deadwood or driftwood. They have a weeping growth habit, so they must be anchored for quite a while to allow them to develop a large root system that can support the weight.

If you’re new to the epiphyte world, this is a good genus to start with. These plants don’t require buckets of water to survive (they are commonly referred to as cacti, after all), though they do need some humidity.

Spray them every day with a mister unless you live somewhere humid.

These species may grow outside in Zones 10 to 12. Provide yours with a moderate amount of water and indirect light. They can be grown in moss, bark, and rocks.

Our guide to growing Christmas cactus can help you learn more about how to raise these plants.

18. Staghorn Fern

Staghorn ferns, species in the Platycerium genus, get their common name from their antler-like leaves. Some species are referred to as elkhorn ferns instead because of their thinner leaves, which are technically called fronds.

P. bifurcatum is perhaps the most common species found in stores, and it lends itself exceptionally well to growing as an epiphyte as does P. hillii. P. superbum and P. angolense are striking, but are a bit more difficult to raise, especially without soil.

In Zones 9 and above, you can grow these ferns outside. In cooler areas, you can move them indoors when temperatures drop below 40°F.

They grow well in wire baskets or on pieces of wood covered with sphagnum moss. You can often find these anchored to wooden boards to resemble mounted antlers.

Allow the substrate to dry out completely before adding more water. It’s easy to overwater these, even when they are grown as air plants, and oversaturation may cause rot.

Staghorn ferns don’t have stems that you can use to attach an anchor, so wrap your anchoring material around the basal fronds instead.

Don’t wrap any around the younger, green fronds. These will break or become damaged. Give them a moss base instead.

Staghorn and elkhorn ferns need bright, indirect or filtered light.

Find more tips on caring for staghorn ferns here.

19. Tillandsia

Tillandsia species are often referred to as air plants. This genus is made up of over 600 species of epiphytes that can grow on other plants or rocks. These plants don’t get any nutrition or water from their roots, and they are solely used as anchors.

Tillandsia plants can be xeric or mesic. Xeric types grow in dry, desert climates, and mesic types in humid rainforests. Look for a xeric type if you aren’t especially diligent at watering your plants.

While you can memorize a list of xeric species, it’s actually pretty easy to identify them. They have silver rather than green leaves, and lots of trichomes – the hairy growth that helps the plant capture moisture. The leaves are usually flat, rather than rounded.

You can learn more about the different types of Tillandsia in our guide.

To water, you must spray or soak them. You can’t water whatever material the plant is anchored to if you intend to provide moisture for your plants because the roots don’t absorb water.

Speaking of, the range of objects you can anchor air plants to is astounding. You often see them growing in glass balls with rocks in the base, but I’ve also seen them placed in shells, or held in the air by decorative wire.

You might see them grown on large, porous rocks, on bamboo strips, in trays, and even in macrame. Don’t be afraid to get creative!

You can keep these outdoors in Zones 9 and above. They can handle direct morning light and indirect light for the rest of the day.

Check out our comprehensive guide to growing air plants for all the info you need to succeed.

Take to the Sky with Epiphytes

The world of epiphytes is fascinating, filled with an astounding array of sizes, shapes, foliage colors, flowers, and growth habits.

They’re all beautiful and all fascinating when grown as epiphytes, and outdoors in suitable regions as well.

Which species is calling your name? Have you grown any in soil and you’re thinking of taking them to the sky? Let us know in the comments below.

If you’d like to learn more about these fantastic species, we have some guides that we hope you’ll find useful, including:

Please change “Heart-leaf Philodendron” to “Philodendron Brazil/Basil.”

For the first picture for Monstera, it is actually an epipremnum pinnatum. Monstera deliciosa leaves are usually rounder and have holes in their leaves as they mature and grow larger.

Thank you for the catch! You’re right, that’s not a Monstera deliciosa plant. The image has now been changed.

Thanks for the comprehensive article!