Epiphyllum spp.

Orchid cacti, or epiphyllums, are forest cacti with long, flat, succulent stems that produce incredible blooms. These long-lived plants are easy to care for, fun to propagate, and stand up well to neglect!

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

The world of epiphyllums is a fascinating one – but it can also be somewhat confusing. In this article we’ll disentangle those head-scratching snarls, and provide guidance for every step of growing these extraordinary cacti.

I’m going to focus primarily on growing epiphyllums as houseplants here, though I’ll offer care tips for outdoor orchid cacti specimens as well.

Here’s what we’ll cover:

What You’ll Learn

What Are Epiphyllums?

Epiphyllums are primarily epiphytes, but some may also be lithophytes, that hail from tropical or semi-tropical forests.

While epiphytes derive moisture and nutrients from precipitation and the air, and typically live on host plants in the wild, lithophytes grow on rocks.

Known as “orchid cacti” these plants are recognizable by their long, succulent, flattened stems which are typically at least a couple of inches wide.

The foliage of these plants can grow to impressive lengths, depending on the species or cultivar, reaching two feet to upwards of ten feet.

The stems generally have an arching, weeping growth habit, making them well-suited to growing in hanging baskets.

The leafless stems of epiphyllums are smooth and tend to be flat, though some exhibit three-sided growth. These stems have notched margins, and can produce aerial roots.

The big attraction for fanatics of these spineless cacti, though, is their flowers.

Most blooms are four to eight inches across, though the blooms of some orchid cactus cultivars can reach a staggering 14 inches wide. They are, to put it mildly, rather showy.

Some of these jungle cacti bloom only at night and are pollinated by bats or long-tongued moths, while others are day bloomers, attracting diurnal pollinators.

Flowers are produced from the notches in orchid cactus stems, at areolas, and these blooms tend to be short-lived. When pollinated, they produce edible fruits similar to pitayas, which are sometimes referred to as “pods.”

You can learn more about epiphyllum seed pods in our article. (coming soon!)

In addition to producing flowers, areolas produce secondary stems, which may appear to be leaves – but aren’t!

However, when new stems first appear, they are often rounded and bristly, only flattening and losing their bristles as they mature.

Remember when I mentioned that some confusion exists involving epiphyllums? Now that you have an idea of what they look like, it’s time to do some untangling.

When asked the question, “What are epiphyllums?” an honest answer would be, “Well, that depends.”

The term “epiphyllum” refers to three types of cacti. Or four, if you dig deep.

One use of this term refers to the members of the Epiphyllum genus. Let’s call these plants Epiphyllum with a capital E. The members of this genus include species such as E. oxypetalum, also known as “queen of the night,” and several others. I’ll refer to these as “species plants.”

Here’s where the confusion starts to come in. The term “epiphyllum” also refers to certain hybrid plants whose lineage might include members of the Epiphyllum genus – but might not. I’ll refer to these as hybrids or cultivars.

Some of the cacti used to create these knock-out hybrids – members of the Disocactus genus as well as the Selenicereus genus – used to be considered part of the Epiphyllum genus but have since been reclassified for taxonomic purposes.

These former members are also frequently referred to as “epiphyllums.”

The good news is, whichever type you have, the care they require is similar.

There’s a fourth use of the term “epiphyllum” which isn’t quite as widespread. This term was formerly used as a genus name for yet another group of cacti, which is now known as Schlumbergera, and which includes the plants known as Christmas cacti or holiday cacti.

We won’t be covering the Schlumbergera plants in this article – you can learn more about them in our complete guide to growing Christmas cactus.

So, just to recap – Epiphyllum with a capital E is a genus used for botanical naming purposes, epiphyllums with a lower-case e may be members of that genus, former members of that genus, or hybrids that have very similar genetic ancestry and care needs.

Whew!

Now that this epic ball of confusion has been untangled, let’s learn a bit more about where orchid cacti come from so we can understand how to best care for them.

Cultivation and History

Plants in the Epiphyllum genus are native to Central and South America. Members of this genus have also naturalized in places like Florida, the Caribbean, and parts of Asia – a fact which attests to the ease with which they grow.

In the wild, epiphyllums grow in tropical or semi-tropical forests in dappled light and warm, humid conditions.

Epiphyllums are related to the much more well-known holiday plant, the Christmas cactus (Schlumbergera spp.), but also to other houseplants such as rat tail cactus (Aporocactus flagelliformis) and the landscaping cactus par excellence, prickly pear.

Epiphyllums share a similar native range to species in the Disocactus and Selenicereus genera, members of which have been used to create hybrid epiphyllums.

In fact, the reason that epiphyllums cross so easily with species of Disocactus and Selenicereus is because the three genera are part of the same tribe, the Hylocereeae, within the cactus family.

Although, I’m also willing to hazard a guess that humans care a lot more about drawing lines between taxonomic categories than plants do!

Epiphyllums are commonly called “phyllocacti,” “climbing cacti,” “leaf cacti,” and sometimes “epicacti.” And though they are not related to orchids, they are often called “orchid cacti” because of their stunning blooms.

They are also lovingly referred to as “epis” or “epies” by their fans.

Orchid cacti were first bred to create hybrid cultivars in the 1800s. There are now thousands of different hybrid cultivars with seemingly endless bloom variations.

And while epis make great houseplants, they can also grow outdoors year round in USDA Hardiness Zones 10b to 12a when provided with the right soil and water conditions.

Propagation

While it’s possible to grow orchid cacti from seed, that method requires sourcing the seed, which in itself is not an easy task – you’ll likely have to grow your own.

So, for the purpose of this article, we’re going to stick to a much easier method : propagating epiphyllums from cuttings.

From Cuttings

Here’s what you’ll need for this project: a cutting that is six to nine inches long, growing medium, and a four-inch nursery pot. Rooting hormone can also be used but this is optional.

If you’re taking a cutting from a mature specimen, use a sterilized pair of scissors to cut the stem cleanly at its base.

Next, you’ll want to allow the cutting to cure. If you’re using rooting hormone, such as Olivia’s Cloning Gel, go ahead and apply it to the cut end of the stem first.

Need your own jar of Olivia’s Cloning Gel? You’ll find it in a selection of sizes from Arbico Organics.

Allow the cutting to cure for a week to 10 days in a cool, dark place. You’ll know it’s cured when a callus has formed on the cut end of the stem.

Next, fill the nursery pot with potting medium, leaving an inch of space between the soil surface and the rim. You’ll find potting medium recommendations a little later in the article.

Insert the cutting two to four inches deep in the potting medium, so there are two to four areoles beneath the soil.

Here’s the hard part – don’t water the soil right away. Wait one to two weeks before watering, and in the meantime, mist the cutting daily (or more often during hot weather) to help keep it hydrated.

You’ll find step by step instructions on propagating queen of the night from cuttings in our guide. (coming soon!)

How to Grow

Epiphyllums are easy to grow. In fact, they are even quite tolerant of neglectful plant parents.

However, for the happiest houseplants, it’s best to start off on the right foot by learning which growing conditions will allow them to thrive – even when subjected to a bit of neglect.

Here’s everything you need to know:

Sun

Epiphyllums grow best in 50 to 75 percent shade.

Indoors, this means they should be grown primarily in bright, indirect light.

For those growing orchid cacti outdoors, they should be hung under trees in dappled shade, or grown under laths or shade fabric.

Indoors or out, expose epiphyllums to a few hours of direct sun in the morning, which will help promote flowering.

However, avoid direct sun during the middle of the day. Midday sun can burn foliage quickly, and sunscalding can be apparent right away or it may show up later.

When temperatures are particularly hot, err on the side of providing more shade to help the plant resist heat stress.

If you’re not sure whether your specimen is getting the right amount of light, watch out for leaves that are wilted and yellow, or sunburned. These symptoms are signs that the epiphyllum is getting too much sun.

Instead, your orchid cacti’s foliage should be light to dark green, while new foliage is often tinged with red.

Soil

It’s helpful to know what conditions a wild plant would have grown in when choosing soil for our houseplants.

As for epiphyllums, they are epiphytes or lithophytes that grow in shallow deposits of organic matter.

That means they don’t need a large amount of soil for their roots, but they do need good root aeration, good drainage, and a medium that can retain moisture.

Despite these preferences, orchid cacti are rather flexible about their growing medium, so you have options, as long as the medium contains organic matter and is chunky and loose.

Some growers like to include some leaf compost in their growing medium – not a bad idea, since these species would grow in decomposing leaf litter in their natural habitats.

Other gardeners like to use cactus soil with added orchid bark.

And enthusiasts at the Epiphyllum Society of America recommend potting orchid cacti in a medium that is made up of one-third coarse material.

My premixed growing medium of choice for epiphyllums is De La Tank’s Houseplant Mix. It contains chunky coconut husks, pumice, compost, and fertilizer.

You’ll find De La Tank’s houseplant mix for purchase in a one-, eight-, or 16-quart bag via Arbico Organics.

In most locations, gardeners growing epiphyllums outdoors year-round will find it easier to keep them healthy when planted in pots filled with an appropriate growing medium as opposed to growing them directly in the ground, since heavy rainfalls and insufficient drainage can cause disease problems.

Water

Epiphyllums are cacti, but these cacti come from forests, not deserts. While they do have succulent foliage, they prefer growing conditions that are more moist than their relatives from arid regions do.

So, try to keep the epiphyllum’s growing medium moist, but not soggy, and avoid letting the potting medium dry out completely between waterings.

A good rule of thumb is to water when the top third of the soil is dry. You can insert a finger into the growing medium to check this.

Or, instead of using a finger to test for dryness, try using a moisture meter to check the specimen’s growing medium. You’ll learn more about using moisture meters in our article.

If in doubt, err on the side of underwatering rather than overwatering, since too much water can cause plants to rot.

How frequently you will need to water will depend on the conditions in your home – or outdoors, if you are growing your epis outside.

Like many houseplants, epiphyllums have changing water needs throughout the year.

From spring to summer, water regularly when the top third of the soil dries out. This may mean once a week, or more frequently during hotter weather.

If the orchid cactus is outdoors and getting rainwater, do make sure it’s not getting too much – in their natural habitats epiphyllums would not be out in the open, and therefore would not be exposed to torrential downpours.

In late summer to early fall, start to reduce the frequency of waterings as hot temperatures taper off.

Finally, in late winter, withhold water for a month to provide a period of rest that will encourage blooming in spring or summer.

Temperature

Epiphyllums, like many houseplants, are most comfortable in the same temperature ranges where their human caretakers are also comfortable – for these plants that’s within a range of about 40 to 80°F.

Specimens sometimes survive freezing temperatures, but it’s best not to push your luck.

They can also tolerate hotter temperatures above 80°F, but with hotter weather it’s best to provide additional water.

During winter, move these plants to cooler locations, where temperatures between 52 and 57°F will help to encourage flowering come spring or summer.

While seeking out the location that will keep your epiphyllum in the right temperature range, avoid hot spots such as radiators or heat vents, and cold air from sources such as exterior doors and drafty windows.

Humidity

In their natural habitats, ambient humidity would fulfill a portion of their moisture needs, so water vapor is an important element of the environment for these cacti.

Epiphyllums will be happiest in conditions with at least 50 percent humidity.

If you aren’t sure what the humidity level is in your home, you can check it with a humidity gauge. I prefer to use an analog humidity gauge that doubles as a thermometer, such as this gauge which requires no batteries or electricity.

Small Thermometer and Humidity Gauge

This small, green gauge is available from Tentop via Amazon.

If you determine that your indoor moisture is below the ideal range, there are a few different ways you can increase relative humidity.

Misting the epiphyllum’s foliage with water from a spray bottle is an easy, low budget way to start.

I like to keep a few clear glass spray bottles scattered around my home to mist my moisture-loving houseplants.

You can purchase a pack of two sixteen-ounce spray bottles from Sally’s Organics Store via Amazon.

Another means of raising humidity levels is to situate your houseplants in groupings to create a more humid microclimate.

Finally, if you want to step up your efforts a bit, using a humidifier near orchid cacti is an excellent way to help raise relative humidity.

And remember, even those who live in humid climates may experience dry air during the winter when the heat is on, so monitor conditions in the winter as well as the summer.

Growing Tips

- Grow in bright, indirect light with a little direct sun in the morning.

- Use a well-draining, chunky growing medium.

- Keep soil moist but not soggy.

Maintenance

While orchid cacti aren’t difficult to keep as houseplants, there are a few tricks you can keep up your sleeve to enjoy them fully and keep them looking magnificent.

Flowering

If you’re interested in epiphyllums for their blooms, you’ll want to start off by knowing when to expect flowering in the first place.

In general, species plants bloom in the spring, while hybrids bloom in summer or fall.

Also, epiphyllums can take between three and seven years to produce blooms, depending on the species or cultivar and the specimen’s growing conditions.

Now that you know what to expect, there are several steps you can take to encourage blooming.

First, make sure the cactus is in an appropriately sized pot. We’ll go into more details about this in the repotting section of this guide, coming up shortly.

For epiphyllums to set blooms, they also need to have enough light. Exposing plants to some direct sunlight in the morning will encourage blooming.

Also, epiphyllums are stimulated to produce flowers after going through a semi-dormant period in the winter. So, expose orchid cacti to cooler, drier conditions in late winter. Review the temperature section above for specifics.

Finally, like Christmas cacti, long, uninterrupted nights can help epiphyllum bloom production.

One way to satisfy this requirement while providing cooler winter conditions simultaneously would be to situate your epiphyllum in a cool, unused or rarely used room on the north side of your home during the winter months.

Finally, once the big moment arrives and you notice buds on your epi, don’t move it. This can cause buds to drop off the plant.

Fertilizing

Starting about a month after flowering is finished for the year, begin fertilizing your orchid cactus with a gentle, balanced fertilizer to encourage foliage growth.

Young orchid cacti that are not expected to bloom can be fertilized this way starting a bit earlier, in early spring.

Dr. Earth’s Pump and Grow Indoor House Plant Food is a gentle fertilizer with a ratio of 1-1-1 (NPK) that will help nourish the cactus and encourage foliage growth.

Dr. Earth’s Pump and Grow Indoor House Plant Food

You’ll find a 16-ounce pump container of Dr. Earth’s Pump and Grow Indoor House Plant Food available for purchase at Arbico Organics. This liquid fertilizer is made from recycled food scraps.

This or a similar product can be applied every two weeks from spring through autumn.

And to encourage blooming, switch to a low-nitrogen fertilizer in late autumn, then stop fertilizing during winter, during the epiphyllum’s cold, dry “rest” period.

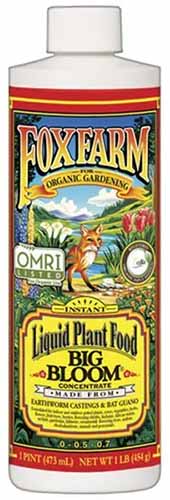

In later winter, resume applying low-nitrogen fertilizer, such as Fox Farm’s Big Bloom Plant Food Concentrate, which has an NPK ratio of 0.01-0.3-0.7.

Fox Farm Big Bloom Plant Food Concentrate

You’ll find Fox Farm’s Big Bloom Plant Food Concentrate available for purchase via Nature Hills Nursery.

Be sure to follow the manufacturer’s instructions for applying each of these fertilizers.

In the wild, orchid cacti grow in deposits of organic matter where they receive low doses of nutrients, so whatever fertilizer you choose, make sure it’s a gentle option that’s suitable for cactus houseplants.

Any fertilizers with NPK ratios higher than 10-10-10 for foliage growth or 02-10-10 for flowering should be diluted.

To learn more about plant nutrients and NPK ratios, be sure to read our article.

Repotting

Epiphyllums need to find a sweet spot in their pots.

They like to be in a somewhat snug pot, otherwise they won’t bloom. But likewise, if they are too root bound, they will stop growing and won’t bloom that way either.

Having said that, you may only need to repot your specimen every five to seven years.

When it’s time to repot, plan this project for the spring or summer during a period of active growth, and wait until the plant has finished flowering.

Choose a new pot that provides the epiphyllum’s roots with just a bit more room – and be sure to choose a pot that will support the weight of the plant.

Place a layer of potting medium in the bottom of the new pot.

Next, remove the specimen from its old pot. Try to minimize your impact on the specimen’s root ball while transplanting; just brush a little soil off the root ball gently.

Now place the specimen in its new pot, situating it so you leave about an inch of room between the top of the root ball and the rim of the pot, to make watering easier.

Fill in around the root ball with potting medium.

Rather than watering right away, wait for a week, then water as usual.

Offering Support

Most epiphyllums have a trailing growth habit that works beautifully in hanging baskets.

But this isn’t your only option – and hanging baskets may not be the best selection for gardeners whose specimens display more upright and less weeping growth.

For a more upright display, orchid cacti can be supported by a trellis or stakes.

Small stakes, encircled with twine or string, can be used to create a “cage” for the plant to grow within.

Head to Amazon to purchase a 25-pack of three-foot, natural bamboo stakes from the GROWIT Store.

Or you might require a large trellis which can help support bigger, more mature plants, such as this obelisk-style, steel trellis.

Powder-Coated Steel Garden Obelisk

Five-, seven-, and eight-foot obelisk-style trellises are available for purchase with either a bronze or an antique copper finish at Plow and Hearth.

Trellising isn’t the only need for support you might encounter with your leaf cactus.

As with hoyas, these plants have a massive amount of foliage compared to the size of their root balls, so the size of their pots will be relatively small, often making them somewhat unbalanced and likely to tip.

Placing an even layer of rocks or pebbles on the surface of the growing medium can help balance out the weight of the foliage and prevent the plant from tipping over.

Deadheading

Spent orchid cactus flowers can be deadheaded as needed.

Be sure to use a pair of sterilized scissors or garden pruners for this job, to avoid spreading disease pathogens.

You can find more tips on deadheading spent flowers in our article.

However, if there’s a chance that the blooms were pollinated and you’d like to try growing fruit or saving seeds from your specimen, leave the flowers on the orchid cactus to allow fruit to develop.

Keeping Specimens Identified

If your encounter with an epiphyllum isn’t a mere flirtation but the start of your own personal collection full of outrageously glorious hybrids, you’ll need to have a way to tell them apart.

After all, when orchid cacti aren’t in bloom, one can look much like another.

Some growers write a specimen’s species or cultivar name directly on a stem with a permanent marker. This is often practiced when sharing cuttings as well. But it’s certainly not the most attractive way to identify your orchid cacti!

Plant tags are a good alternative. And while writing names on plastic plant markers with a pen is an option, even permanent markers sometimes turn out to not be so permanent.

Instead, I like metal tags that are soft enough that you can engrave them with a pencil or pen.

By bearing down onto the metal as you write, it becomes engraved with the name – and there’s no more worry about ink being washed off, because the “engraved” name will still be there.

Pack of 50 Aluminum Plant Tags

Want to try this method of identifying your plants? You’ll find a pack of 50 aluminum plant tags for purchase from the PinCute Store via Amazon.

Species and Varieties to Select

Choosing which type of epiphyllum to grow is lots of fun – there are so many choices! But some plant lovers may feel overwhelmed by the huge number of options.

So, before we look at a selection of recommended varieties and species, let’s talk a little bit more about how various options will present themselves.

Epiphyllums are sold as potted plants, rooted cuttings, or unrooted cuttings.

Some nurseries sell specimens that have been identified by their species or cultivar name, while others may just offer selections labeled as “white,” “yellow,” or “red,” in reference to bloom colors.

When deciding on a bloom color, be aware that straight species epiphyllums – which tend to have white flowers – bloom at night.

On the other hand, colorful cultivars with red, pink, purple, yellow, or orange flowers are more likely to bloom during the day.

Epiphyllums with smaller flowers tend to hold their blooms longer, for two or three days, while the largest blooms tend to be quite short-lived, remaining open for only one night.

Another important distinction is that hybrids tend to be more compact while species plants can produce stems that grow to staggering lengths – up to 20 feet or more.

Now, let’s start looking at a few options!

Ackermannii

Commonly known as “red orchid cactus,” Disocactus ackermannii was formerly classified as an Epiphyllum species but was transferred to the closely related Disocactus genus.

It’s still commonly referred to as E. ackermannii, which is considered a synonym.

This spring-blooming species bears red flowers that reach up to six inches across, remaining on the plant for a few days.

Stems range from seven inches to three feet long and have prominent veins and undulating margins.

D. ackermannii received the Royal Horticultural Society’s Award of Garden Merit in 2012.

D. Ackermannii Red Orchid Cactus in 6” Pot

You’ll find a live, red-flowered D. ackermannii orchid cactus plant available for purchase in a six-inch pot from Hirt’s Gardens Store via Amazon.

Guatemalense

Commonly known as “curly locks orchid cactus,” this naturally occurring subspecies has undulating stems that look like big, wavy locks of hair on older specimens. Stems have a prominent midvein.

Classified as Epiphyllum hookeri ssp. guatemalense but also sometimes as E. guatemalense, this member of the Epiphyllum genus produces white blooms.

This variety is also sometimes called “curly sue” or Epiphyllum guatemalense ‘Monstrose.’

Curly Sue E. Guatemalense in 6” Pot

You’ll find curly locks cacti in six-inch pots available for purchase from the House Plant Shop via Walmart.

You can learn more about growing curly locks orchid cactus in our article. (coming soon!)

Oxypetalum

“Queen of the night” is the common name for the most well-known member of the Epiphyllum genus, E. oxypetalum.

This orchid cactus species, also known as “Dutchman’s pipe cactus,” has funnel-shaped, night-blooming flowers that can reach over seven inches wide.

Queen of the night’s showy, fragrant blooms are white with gold sepals, and are short-lived, lasting one night only.

E. oxypetalum, a forest cactus, like the other Epiphyllum species, has stems that can reach impressive lengths – up to 10 feet or more.

This species is also known as “lady of the night,” and “night-blooming cereus.” It shares those two names, as well as “queen of the night” with a few types of desert cacti that are members of the Cereus genus, such as C. peruvianus.

You’ll want to be sure you choose the right “queen of the night” for your purposes, since these two types of cacti have different care needs.

E. Oxypetalum Queen of the Night Plant in Grower’s Pot

You’ll find a queen of the night epiphyllum in a grower’s pot from the Easy to Grow Store via Amazon.

Want More Options?

This selection of species and varieties is just a light skim of the surface – there are so many other incredible options! You can discover a large selection of these in our guide on 23 of the most fabulous types of epiphyllums.

Managing Pests and Disease

Many gardeners grow epiphyllums without encountering pest or disease problems, but it’s always good to know what to be on the lookout for.

Gastropods

Gardeners growing orchid cacti in the yard year-round or placing houseplants outdoors during the warm months may have to contend with some competition.

While we want to admire the lovely foliage and flowers of these plants, snails and slugs may prefer to express their admiration via their sense of taste.

These mollusks will only be a problem for specimens grown outdoors or in a greenhouse.

You can learn all about protecting your outdoor plants from slugs and snails in our article.

Insects

Snails and slugs aren’t the only leaf connoisseurs you might encounter when growing orchid cacti. Keep reading to learn more.

Mealybugs

If I were giving out awards to houseplant pests – which, sorry bugs, I’m not! – mealybugs would get my vote for “Most Creative Pest Costume.”

These sucking insects look like they have dressed themselves up as bits of fluff, or with a bit of imagination or some bad eyeglasses, teeny-tiny sheep.

Whether you find these puffy white pests kind of cute or downright detestable, you don’t want to find them on your houseplants.

They will suck valuable nutrients from the stems of orchid cacti and can leave sticky trails of honeydew behind, which can foster fungal growth.

If you encounter these pests, I recommend first trying to remove them by spraying them with a strong jet of water to knock them off.

Wait a week or so, and if you find more mealybugs, my next recommendation is to treat your orchid cactus with nontoxic neem oil, which is safe for humans and pets.

Monterey neem oil is available in an assortment of jug sizes at Arbico Organics.

Follow the manufacturer’s instructions for applying this project to the soil as well as the foliage.

Be prepared to reapply until populations of mealybugs have disappeared from your plant’s foliage. It may take a few applications until they are gone.

Learn more about identifying and controlling mealybugs in our article.

Scale

Second place for the imaginary “Most Creative Pest Costume” award goes to scale insects. (Way to go, guys!)

When you have a scale infestation, you may not notice the insects until your plant starts to look sick. On closer inspection you will find some spots that look like bits of dirt or discoloration but are in fact insects that have small domes over them to help them blend in with the plant.

If you aren’t sure whether it’s scale or just a blemish, try scraping one of the spots off with a fingernail – if it scrapes away and produces a liquid, congratulations, you’ve got scale!

Scale insects are related to mealybugs, and like those pests, they will suck nutrients from plant tissues, weakening specimens and potentially killing them.

And as with mealybugs, scale infestations can be treated with neem oil. Apply once a week if needed, continuing treatment until pests are gone.

You’ll find more help on dealing with these pests in our complete article on identifying and controlling scale insects.

Spider Mites

Spider mites are another common houseplant pest, and they can target epiphyllums too.

These pests use the “costume” tactic of being almost unspottable, they are so tiny.

Gardeners may notice sickly-looking plants before they spot the culprit – a tiny arachnid (but not an actual spider) that sucks juices from plant tissue, leaving foliage looking stippled with tiny white or yellow spots.

When infestations are large, webbing will become apparent on foliage as well.

This pest is more likely to be a problem on stressed plants, so be sure to keep plants properly watered, especially during hot weather.

If you notice spider mites on your orchid cactus, first try removing them with a strong jet of water. That may be all that is necessary.

If that proves to be insufficient, neem oil can also be used to kill spider mites.

Whatever pest you’re dealing with, for specimens kept outdoors, be sure to learn the basics of Integrated Pest Management or IPM. Practicing IPM will allow you to employ strategies to eliminate pests while protecting beneficial insects.

Learn more about how to deal with spider mites in our guide.

Disease

You may get lucky with your epi and never have any diseases to worry about, but it’s nonetheless good to keep these illnesses on your radar, just in case.

Cactus Virus X

Cactus Virus X (CVX) is caused by a pathogen that can affect different members of the cactus family.

Signs of this virus include yellowing stems and dead plant tissue, but plants can also be asymptomatic. Some gardeners discover the presence of this disease only during flowering, with the appearance of discolored blooms.

This virus can spread throughout a cactus collection if good hygiene isn’t followed.

To prevent the spread of this (and other) diseases, wash your hands between handling different specimens, and sterilize tools as well.

Infected specimens may not show signs of illness, and if spread is not a concern – perhaps you only have one cactus! – then the specimen can be kept.

Discarding infected specimens may be prudent for gardeners who wish to prevent disease spread.

Root Rot

Root rot is only likely to occur when the plant’s roots stay too wet.

This can happen if the growing medium doesn’t drain well enough, if the specimen is in a pot that is too large, or if watering is just too frequent. Usually, the problem comes from a combination of these causes.

Signs of root rot can include yellowing stems or stems that look like they are drying out since this disease can prevent the plant from getting enough water and cause dehydration.

What’s more, rotting roots can harbor bacteria and fungi which can sicken the plant further.

The best treatment is prevention – make sure to choose a chunky, well-draining potting medium, and a pot of an appropriate size in comparison to the root structure so the growing medium doesn’t stay too wet.

These plants have shallow root systems, and rotten roots can quickly become unsalvageable. For specimens that have lost their roots to rotting, the best recourse is to take cuttings of the stems and propagate new plants.

Spotting

Various issues – both physiological and pathogenic – can cause spotting on epiphyllum stems, and some causes remain unknown.

Some varieties are more prone to this problem than others, so you may wish to avoid cultivars that are known to be more susceptible.

Also, avoid fertilizers high in nitrogen, which can make the symptoms worse.

Root rot can sometimes cause spotting, so inspect the plant’s roots to see if they look healthy or not, and act accordingly.

Some spotting is caused by leaving branches wet in cool temperatures, so it’s preferable to water in the morning, and not on cold days.

Best Uses

As houseplants, epiphyllums fulfill a dual interest – they produce masses of succulent, green foliage, and bear strikingly ornamental flowers.

Orchid cacti are an obvious choice if you are looking for a trailing succulent to display in a hanging basket.

On the other hand, specimens that are staked or trellised rather than being placed in hanging baskets can create dramatic vertical interest.

These cacti are excellent picks if you are looking for a nontoxic houseplant, a feature which will be of special interest for households with curious children or mischievous pets.

And with edible fruits, you can consider growing these as part of your indoor garden and sampling the harvest.

Finally, for gardeners in Zones 10b to 12a, these plants make striking ornamentals (or fruit producers!) when planted in baskets or planters outdoors.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Succulent epiphyte and/or lithophyte | Flower / Foliage Color: | White, yellow, orange, red, pink, purple/green |

| Native to: | Central America, South America | Maintenance | Moderate |

| Hardiness (USDA Zone): | 10b-12a | Soil Type: | Cactus soil with chunky organic matter added |

| Bloom Time: | Spring-fall | Soil pH: | 5.5-6.5 |

| Exposure: | Bright indirect light with some direct morning sun | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Time to Maturity: | 3-7 years to bloom | Attracts: | Bats, moths, other pollinators |

| Planting Depth: | 2- 4 inches (cuttings), level with top of root ball (transplants) | Companion Planting: | Christmas cactus, fern, Norfolk Island pine, orchid, spiderwort |

| Height: | 2-10 feet | Uses: | Indoor potted succulent collection, stand-alone specimen; outdoor xeriscaping ground cover |

| Spread: | 2-10 feet | Order: | Caryophyllales |

| Growth Rate: | Slow to fast, depending on variety | Family: | Cactaceae |

| Water Needs: | Moderate | Subfamily: | Cactoideae |

| Tolerance: | Humidity, neglect | Genus: | Epiphyllum |

| Common Pests and Diseases: | Aphids, fungus gnats, mealybugs, scale, spider mites; cactus virus X, root rot, spotting | Species: | Baueri, cartagense, chrysocardium, grandilobum, hookeri, laui, oxypetalum, phyllanthus, pumilum, thomasianum |

Feel Those Epic ‘Phyllums

Hey plant lover, are you getting all the feels for the epis? I’m right there with you.

And equipped with all of this knowledge, you’ll be filled not only with delight and admiration, but also with the triumph of keeping these plants happy and healthy for many years to come.

If you’re growing orchid cacti and would like to share your experiences and plant photos or ask a question, feel free to reach out via the comments section below. We’d love to keep sharing the epi love with you there.

And if you’d like to keep exploring the wonderful world of cacti and succulents, you’ll find more to dig into right here:

Thank you this is very helpful as I am new to growing these plants.

Sherry, thanks for letting us know you found the article helpful, I’m glad to hear it! Epiphyllums are a lot of fun – I hope you will enjoy the process!

Your article is super informative. I love orchid cacti because my mom had quite a few of them and they are a good memory of her. Recently a bunch of the leaves have been dying. I’ve looked at so many articles online, but I still can’t find out what’s wrong. Hopefully a picture posted here will help me out. Thank you in advance. (I’ve tried attaching photos but I don’t see them. Not sure if it worked or not.)

Hi Jane, I’ve managed to retrieve your pictures, for some reason they uploaded but didn’t attach 🙂

Thank you so much for finding the pix I uploaded. ????

Hi Jane, I’m glad you found this article informative, thanks for saying so! Plants can bring so much joy to our lives, but even more so when we have special connections to them via a loved one. What a lovely way to remember your mom. First of all, if you have more than one plant, and any of them are looking healthy, I would recommend quarantining the unhealthy ones until you get this sorted out to avoid the problem spreading. I’ve looked at the photos you’ve attached, and unfortunately the one with the still living, green stem is a bit… Read more »

Kristina,

Thank you for that very comprehensive reply. I appreciate all the time you took to answer my question. The white spots are not scale insects. They are very hard and don’t rub off. The brown spots feel like sap and can be taken off with my fingernail. Here are some better pix. I picked a little harder on a white spot and it came off. It’s kinda like a scab. Thank you so much for your help. ???? (I think I uploaded four pix. I only see one. I hope these ones came through also.)

Hi Jane, You’re welcome! If the white spot came off with some insistent rubbing, I’m still leaning towards thinking it is probably scale. Please look up “cactus scale” and compare with the photos you find. (These can be very hard to recognize as insects.) You may actually have two problems – scale can make conditions ripe for fungal pathogens to grow (which is more like what the orange-blobs look like to me). I would try to remove all the white spots, then apply neem oil to the whole plant. (I’m only seeing one photo, but if one of our editors… Read more »

Thank you again for the generosity of your time. I’ll look that up. Happy day to you! ????

Happy day to you too, Jane! : )

Good day to you Kristina,

Did the other pix ever show up? If not, I’d like to send them again because I’d really like a definitive answer. I don’t think there’s anything pesty left on my cactus. I just like knowing things. Thank you! ????

Hi Jane,

Yes, please try uploading it again. It would help if you can do a close up that is very crisp on that white bump.

Thanks!

I’m not sure if these are any better. When I zoom in really close with my fingers, it still looks pretty blurry. ????????♀️ (I attached two pix but I don’t see them so I’m not sure if they’re showing up on your end.) Thank you.

I guess I’m convinced that the white thing is cactus scale. What do you think the brown gooey spots are? Thank you very much! Both it and the cactus scale are on the first pic Clare was able to retrieve. In a different post, I showed what the brown spot looked like after I scraped it off.

Hi Jane, here are the pics, retrieved again!

Hi Jane, I’m glad Clare was able to get some more pics retrieved for you. My best guess is that the brown gooey spots are fungal pathogens that are taking advantage of the damage made by the scale insects. If you haven’t done so yet, I still recommend treating the plant with neem oil (follow the directions on the product – they usually need to be diluted). Neem oil is both a natural pesticide and a natural fungicide. Usually the plant will need to be sprayed once a week for a few weeks until the problems clear up. And make… Read more »

Thanks ever so much for your further detailed answers. ???? I really appreciate your care and concern. My neem oil arrived yesterday so I’ll be playing nurse to my beloved orchid cactus. I’m so thankful that I found this site and could finally get a solid answer. There are so many sites out there that I almost hate to look. I waste a lot of time that I don’t have, reading through lots of sites trying to find answers. Sites with photos are the best. A most wonderful day to you, Kristina! ????????????????????????

Thanks for your kind comments, Jane! Best of luck and a wonderful day to you too!

This plant has been in my family for a very long time. It did have white fluff on it over the winter. I have seen recommendations to repot but this cactus is very large and I have no clue how to do it if necessary. I keep tweezers next to this plant because I’m always getting stuck. Any help would be greatly appreciated. I really enjoyed your article. Thank you

Hi Vivian, Thanks for posting your photo here and letting us know you enjoyed the article – it’s great to get reader feedback! It sounds like you have a couple of questions/concerns. First, as far as re-potting, you likely don’t need to. Most pro epiphyllum growers don’t repot very often, and at some point in the plant’s life, they stop repotting because these are more likely to produce flowers when they are root bound – ie, when they’re in a very snug pot. However, if you’d like an opinion for your plant, it would be helpful to see photos of… Read more »

Thank you so much for this article! I have been trying to determine the species of cactus I was recently given and I have gotten caught up in the confusion of orchid cactus and fishbone cactus referring to so many different species! Your picture of the new growth with the bristles looks exactly like what I have. Are you able to confirm what species that is? I have attached pictures of mine as well.

Hi Larissa, Glad to know you appreciate this article! First let me say that there are ALOT of hybrids out there – it’s possible to cross epiphyllums with other jungle cacti, so it can be tricky to know for sure what you have unless the breeder or propagator is very sure of their stock. However, I can tell you this – my epiphyllums that are true species and not luck-of-the-draw hybrids do not have prickles on their new growth. However, my fishbone cactus does!Yours could be a cross of different type of jungle cacti, but if I had to hazard… Read more »

I’ve had this plant for a long time and I love it. I think it might be the type of plant that your article is talking about. It’s not doing well and I’m at a loss as what to do for it. Some of the tips are really limp, while the rest of the limbs are hard. The leaves are turning yellow and part of the long leaves are brown. It hasn’t bloomed in a couple of years. Please help.

Hi Melissa, Thanks for posting the photo of your plant – and yes, that’s an epiphyllum. The first thing I’m noticing is that it looks like it’s in a pot that’s much too big. These plants prefer being fairly snug in their pots, so I would recommend repotting it to a smaller pot. You may need to uproot the plant temporarily to see how big the root ball is – and then pick a new pot. (The roots should just barely fit into the pot.) As a reference for you, I have a couple of large epis that have masses… Read more »

Muy clara la informacion. Gracias

You’re welcome! And thank you for letting us know you liked the article!

I have had my plant for about 15 years and last year it had its first single flower. This year I got 2! It’s now has shoots about 7 feet tall with lots of air roots. Can I trim it back?

Hi Gale – your epi is beautiful, and congratulations on your blooms! Yes, you can trim it back if you like – just be sure to sterilize your scissors or pruners first and take care not to prune back more than 1/3 of the growth. And if you want to try propagating your cuttings, we have a guide to epiphyllum propagation right here.

Hope this helps!

Your information is very useful for all my cacti except the one in the photos. It seems to have a disease but doesn’t look like your descriptions. Can you help please?

Hi Eleanor, Thanks for letting us know you found the article useful. Your plant may be an epiphyllum hybrid. Species of the Epiphyllum genus can cross easily with other species, sometimes producing stems like the ones in the photos you posted. Unfortunately this can make it hard to know exactly what type of plant you have, but it’s nonetheless pretty safe to assume that care is the same as for epis. It’s hard to tell for sure based solely on your photos but I think your plant has scale insects on it. I’d recommend you re-read the section on scale… Read more »

Thanks for your very helpful reply and sorry if I’m repeating myself. My first reply disappeared.

First, I had no idea mine might be a hybrid as it was bought as an orchid cactus.

Second I will order some neem oil as well as doing a thorough search for scale which I had on a plant in another room.

Again, thank you for your detailed response. I feel encouraged to keep trying to get a bloom sometime!

Hi Eleanor,

The terms “orchid cactus” and “epiphyllum” can be used very broadly, including intergeneric hybrids – but the word Epiphyllum also refers to a genus. I explain this in more detail in the intro to my article on different types of epiphyllums, in case you’re interested!

Good luck with the scale and the blooms – let us know how it all goes!

Hi, I’m new to these beautiful plants. My neighbor gave me one and she has no idea what it is. If I send you a picture can you tell me which one I have? Thank you

Hi Janice, Thanks for posting your question and photos here! What a nice neighbor and what gorgeous blooms! It can be hard to know for absolute sure with epiphyllums as there are a huge number of cultivars in circulation and these plants hybridize quite easily. However, I strongly suspect your plant is the one that is known by the common name “German Empress.” The scientific name is Disocactus phyllanthoides. I wrote an article about some of my favorite epiphyllums as well, and included that on the list. You can read more about German Empress and other types of epis here.… Read more »

Here is another view of the same plant as the one below. Thanks again