Scale is an umbrella term used to identify nearly 8,000 varieties of wingless, sucking insect species in the order Hemiptera.

One of the more common garden pests, these minute organisms feed on the bark, fruit, and leaves of perennial trees and shrubs using their tiny, straw-like mouthparts.

Different species suck different fluids from the plant, ultimately resulting in the slow depletion of vital plant nutrients.

Infested plants typically appear water stressed, with yellowing leaves and premature leaf drop. Plant parts that remain heavily infested may ultimately die.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

Some species produce sticky, sweet honeydew which can further lead to sooty mold and ant infestations, causing additional harm in the garden.

Not to induce too much fear though – the presence of just a few of these insects will not threaten overall plant health, and even large populations of some species do not damage their plant hosts at all.

For example, African blue basil (Ocimum kilimandscharicum x basilicum ‘Dark Opal’) is quite resilient in the face of a soft scale infestation.

Generally, scale populations are kept in check by beneficial predators and parasites.

However, when the natural order is thrown off balance, perhaps disrupted by ants, dust, or the persistent application of insecticides, additional intervention may be necessary.

Proper identification of the scale family informs appropriate control and potential treatment.

The most common families include armored and soft scales, which can appear on myriad plant species. Others include those found on various cactus, conifer, elm, oak, and sycamore species.

What You’ll Learn

Identification

Though there are thousands of species of scale insects, with about 1,000 occurring in the US, the life cycles and distinction between sexes are fairly consistent across species.

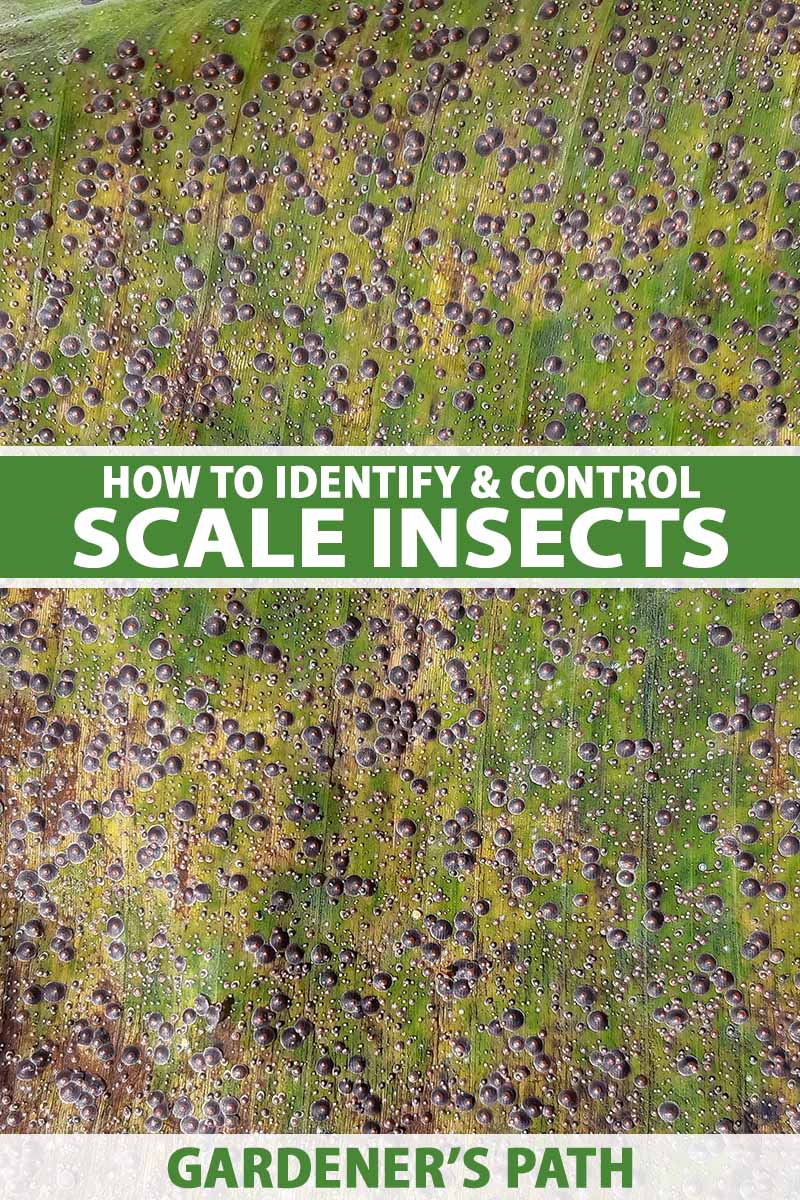

Adult females and immature nymphs of most species appear rounded and wingless, and lack distinct body parts. Dense populations create the appearance of reptilian scales on infested plants, hence the common name.

Adult males typically differ in shape, size, and color to their female counterparts. They are rarely seen but are small, yellow-white insects with one pair of wings and a pair of long antennae.

Some species even lack males completely, in which case, the females reproduce asexually.

Those in the soft scale family (Coccidae), and various species in other families including cottony cushion (Icerya purchasi) and European elm (Eriococcus spurius), suck on the phloem sap of plants, which contains a lot of sugar. These insects consequently excrete a sticky honeydew – highly desirable by ant populations.

In contrast, species in the armored (Diaspididae) and pit (Asterolecaniidae) scale families suck on the parenchyma cells of their host, which do not contain nearly as much fluid, and thus do not secrete the same tasty residue.

Armored

Species in the Diaspididae family, or armored scales, appear almost like tiny barnacles on the exterior of infested plants.

As the nymphs mature, they develop a flattened, protective cover that’s less than 1/8 inch in diameter.

The insect bodies reside underneath this plated armor. If you remove the cover, the insect body will remain alive, though unprotected, on the plant.

Armored scales do not produce honeydew.

Species in this family include cycad (Aulacaspis yasumatsui), euonymus (Unapsis euonymi), oyster shell (Lepidosaphes ulmi), and San Jose (Quadraspidiotus perniciosus) scale.

Soft

Soft scales, species in the family Coccidae, are generally larger and more rounded and humped than armored types. They grow up to 1/4 inch long and have a smooth, cottony, or waxy surface.

Unlike armored types, soft scales do not have a protective covering. If you flip one over, this will remove the insect from the plant entirely.

Soft scales feed on the phloem of plants and excrete sticky honeydew.

This sticky secretion not only drips onto plants and the ground, promoting the growth of black sooty mold, but also attracts ant populations, which feed on the honeydew.

Soft scales include black (Saissetia oleae), brown (Coccus hesperidum), kuno (Eulecanium kunoense), lecanium (Parthenolecanium corni), and tuliptree (Toumeyella liriodendri) scale.

Life Cycle

These insects hatch from eggs throughout spring and summer. They typically mature through two nymphal instars, or growth stages, before reaching adulthood.

Some species change significantly in appearance as they go through these instars, so many types of scales actually appear to develop through more than just two growth stages.

Adult females typically lay eggs that are then hidden underneath their bodies until they hatch, though in some species the eggs hatch inside the female’s body and emerge as live young.

Depending on the species, females can lay anywhere from 50 to 2,000 eggs!

Once the eggs hatch, usually within one to three weeks, tiny yellow-orange crawlers emerge. These are the first instar nymphs.

Crawlers walk across the plant’s surface, or are transported to other plants by wind, people, or birds. One or two days after hatching, crawlers will settle down and begin feeding. Thus begins the second instar nymphal stage.

Settled nymphs may reside in the same spot throughout adulthood, or they may slowly move about.

For example, soft types which feed on deciduous hosts move from the plant’s foliage to the bark in the fall, before the plant’s leaves drop.

Armored

Most species of armored scales have several generations each year.

They overwinter typically as first instar nymphs or adult females, and spend their entire lives in the same feeding spot on the plant.

Soft

Most species of soft scales have one generation per year.

They generally overwinter as second instar nymphs. Most immature soft scales retain their tiny appendages and antennae after settling and are able to move, albeit slowly.

Brown soft scale, however, is an exception. It has multiple generations a year, and both females and nymphs can be present throughout the seasons.

Organic Control Methods

Pest populations are generally kept in check by beneficial predators and parasites.

Regularly monitor the state of the infestation to observe natural population control.

That being said, disruptions to the natural order of things do occur. If this is the case, you can integrate various pest management techniques in order to set your plants up for success.

Cultural

Ensuring optimal plant health is crucial if you want your plants to survive a scale infestation.

When planting and cultivating, make sure your plant receives appropriate sunlight exposure and irrigation.

Small, isolated infestations can easily be controlled with selective pruning. Cut off heavily infested twigs and branches, and remove them from the site for disposal.

In areas with hot summers, pruning to open up canopies can reduce populations of some species through exposure to heat and parasites.

For plants that prove to be exceptional scale targets, you may consider removal and replacement planting.

Physical

For light infestations, mechanical removal may be the best control option. Using a butter knife, gently scrape off each scale insect that you see.

A hard spray-down with the hose is another available control method.

With these techniques, you must be diligent in removing all of the insects from the plant; otherwise, the infestation will persist.

Monitor the plant over the course of the next few weeks, and continue removal until the infestation has been fully controlled.

Biological

Beneficial insects, such as parasitic wasps and certain beetles, lacewings, and mites, are a gardener’s best friend in the face of scale infestations.

Parasitic wasp genera, including Aphytis, Coccophagus, Encarsia, and Metaphycus, are the most common naturally occurring enemies of scale.

These parasitoids lay their eggs underneath the insects. After a wasp egg hatches, the larva that emerges devours the insect and exits through a small puncture hole in the center of the scale’s body.

You can tell when an insect has been parasitized based on the presence of this exit hole. Additionally, the insect will not release any fluid when squished.

Something to note – parasitic wasps typically have a harder time laying their eggs if there is a high population of ants present, protecting the scale.

You can find Aphytis melinus parasitic wasps for release available at Arbico Organics.

Additionally, Arbico Organics also supplies green lacewings, and purple scale predators that are also effective.

If you choose to purchase ladybugs for release into the garden, be sure to look for ones that has been raised in captivity rather than those collected from the wild and shipped elsewhere.

Organic Pesticides

One step beyond mechanical removal, a cotton ball soaked in rubbing alcohol may be all that you need to control a light infestation. The alcohol will dissolve the waxy protective coating, leaving the insect exposed and vulnerable.

Rub a saturated cotton ball over the surface of the infested plant, making sure you come into contact with each individual organism.

Alternatively, to deal with more serious infestations, you can make a solution of one cup isopropyl alcohol mixed with one quart of water and one tablespoon of liquid organic soap, such as Dr. Bronner’s.

Combine in a spray bottle to create a homemade pesticide treatment. Using the flat setting on your hose nozzle, first give the plant a hard spray-down, knocking off as many insects as possible.

Then apply the mixture heavily, making sure to spray the surface as well as the underside of the leaves.

Repeat applications every few days until the infestation is gone.

This practice not only can kill the pests, but also helps to wash off any honeydew present, thus preventing the onset of sooty mold.

Use of insecticides should be your last resort. Many can lead to unintended ecological consequences, so using low toxicity organic pesticides – such as horticultural oil, insecticidal soap, neem oil, and canola oil – is recommended and can prove to be effective.

These applications typically have a low impact on the populations of natural predators and pollinators.

Before applying, give your plant a hard look to see how much of the population is still active, and to evaluate the extent of parasitism. Hold off on spraying if the majority of the pests are already parasitized or inactive.

The optimal time to apply foliar sprays is during the crawler life stage. Because the adult forms are coated in a waxy protective substance, most oils will prove to be ineffective if applied at this phase.

Try to time application when the plant is not in bloom, to avoid negatively impacting pollinator populations.

Make sure to read the label on your selected product to check if the oil is suitable for your species of plant. Some oils should not be sprayed on certain species or mixed with other products.

With contact sprayed oils, insects are suffocated rather than being killed by a toxic material.

Oils are also effective against aphids, whiteflies, and spider mites, yet they are less harmful than other insecticides to beneficial predatory insects.

Horticultural oils are often called narrow-range, superior, or supreme oils, and are specially refined petroleum products.

Oil sprays are best used when the temperature is mild, between 45 and 85°F, at least 24 hours in advance of rain.

Additionally, they should not be applied to plants that are under stress. If drought is a concern, give your plant a healthy drink a few days prior to the application of oil.

Thoroughly spray the affected plant with the application of your choice, making sure to reach the underside of leaves and terminal parts of the plant.

You may need to apply it more than once, depending on the size and spread of the population.

Chemical Pesticide Control

Many forms of chemical control can lead to unintended consequences, such as contaminating water or poisoning beneficial predators and pollinators, and can potentially lead to outbreaks of additional pests.

Careful research of scale species can aid in the selection of chemical controls.

Systemic

Another option for control is to use systemic insecticides. These insecticides are sprayed onto one part of the plant, usually the trunks or roots, and are relocated internally to the leaves and other plant parts.

Systemic insecticides provide an option for control when temperatures limit the use of an oil spray.

The plant absorbs the insecticide into its tissue, which then allows it to enter the plant’s circulatory system and sap. When the insects feed on the sap, they ingest the toxic insecticide and are killed.

The most commonly used systemic insecticides against scale include acephate, dinotefuran, and imidacloprid.

Proper identification of what species you’re dealing with informs appropriate treatment.

For example, some insecticides, such as imidacloprid, may effectively control soft scales and other types, but are not effective in controlling armored or cottony cushion scales. Dinotefuran, however, controls most types.

Careful research into the particulars of the scale infestation will aid in management.

Do not apply systemic insecticides to plants during their flowering season. Systemics can translocate into flowers, negatively impacting the natural enemies and pollinators that are attracted to the plant’s nectar and pollen.

Always read and follow label directions carefully when using any pesticide.

Systems in Check

Not all varieties of scale are seen as garden pests.

For example, cochineal scale, commonly found on prickly pear cactus, is actually sought out by the dye industry for its production of carminic acid, and has recently seen a resurgence in cultivation.

Carmine dye is derived from the insect’s acid secretions and is commonly used as a red colorant for food products, lipstick, and textiles.

There are many available approaches to deal with pests in the garden. In an ideal scenario, pest infestations are kept in check by their natural enemies.

However, organism populations are migrating and evolving at a very quick rate, and infestations may require a gardener’s intervention for plant survival.

A small but vital part in the grander system of ecology, gardeners play an important role in keeping these natural systems in check.

Let us know in the comments section if you have any questions or further advice on dealing with scale!

And for more information on pest management in the garden, be sure to check out these articles next:

why not just brush off the cottony cushion scales with my fingers?

You could try! But they’re usually attached pretty firmly and easier to remove with something a bit tougher, like a fingernail, butter knife, or putty knife. A cotton ball or swab soaked in rubbing alcohol is another effective option for removal.

My infestation resembles the final photo in your article. After reading the article, I am unable to say what type of scale I have. Can you help?

This is brown soft scale, in the final photo.

One of the nice things about managing scale insects is that you don’t typically need to identify the specific species in order to decide how to treat them!

What do you think is the best treatment for heavily infected olive trees? I’ve already treated using systemic pesticides and even heavy oil solutions. These scale are PERSISTANT.

You mean you don’t want to climb up there and swab each branch with rubbing alcohol? 😉 Scale can be tough to target when you’re dealing with a widespread infestation on a large plant. See our guide to growing olive trees for a few tips. I’m not sure what type of pesticides or oil you’ve treated with already or where you’re located. Repeat applications of horticultural oil can work, but you need to reapply as needed and at the best time of year in your growing environment for the best results. Beneficial predatory insects including Aphytis maculicornis and Coccophagoides utilis… Read more »

Thank you so much! I have been struggling with this black stuff and now know what it is and looks like armored scale causing it. I sprayed as a last resort and tomorrow using systemic. I appreciate your help! There’s no one for me to ask. Thank you

Thank you so much! I did not know what i had until your article: it is scale eggs under my some of my bay leaves. I scraped them all off for the other animals to eat. Thank you for encouraging chemical-free, natural solutions.

Thanks for reading, glad the article was helpful!

I have a bug problem recently that is slowly killing my house plants starting with my most sensitive ones. I’ve done everything suggested on every site and used every homemade solution. I also still can’t identify the type of pest that has infected all of my 50 plus plants. Im hoping you may know what these are and how to get them under control. they are incredibly tiny and I am assuming these are the eggs. everywhere I find these the plant starts to die at the tips of leaves.

Hi Austen, do the black spots only appear on the top of the leaves? If so, I would suspect that you’re dealing with thrips and black spots are the fecal remains. If you’ve ever seen bronzing or a silvery color, you can be pretty sure that’s what it is. Visit our guide to thrips to learn more.