Aleyrodidae

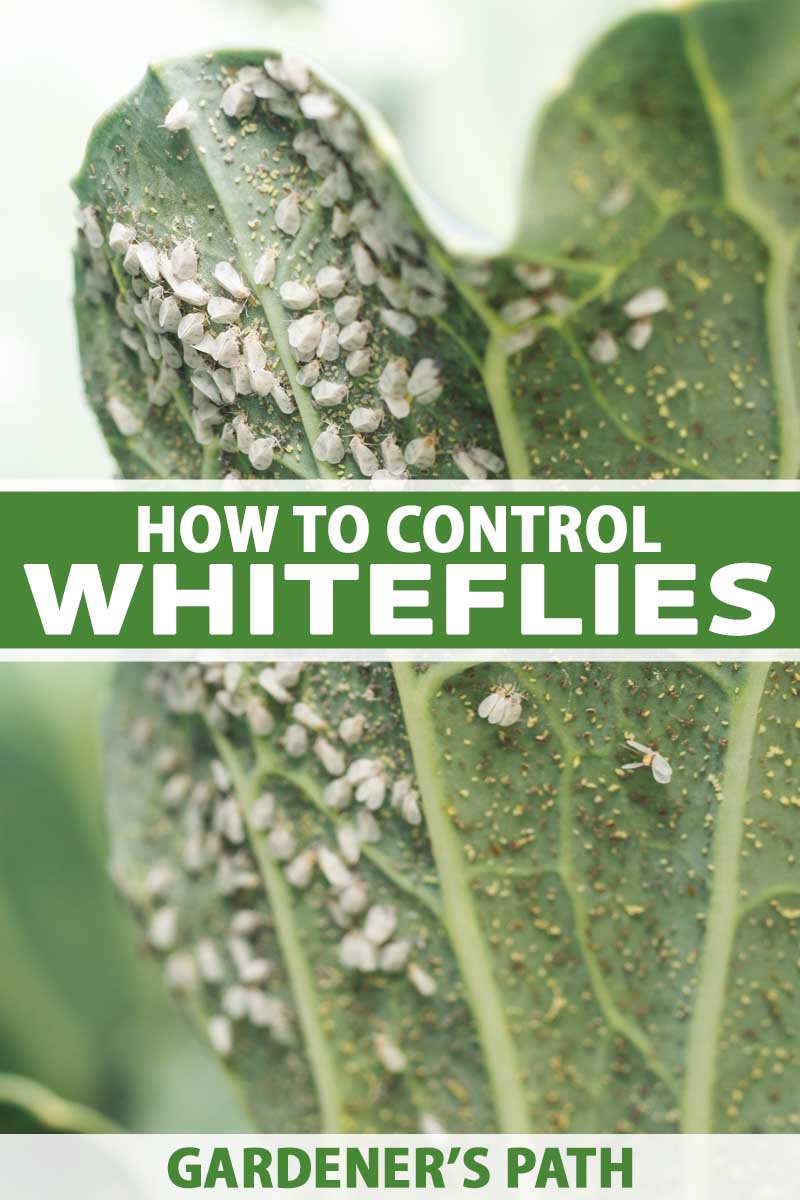

As you walk through your garden, admiring the bright flowers and productive vegetables, a cloud of white insects flutters up from the leaves of a plant as you brush past.

Upon taking a closer look, you notice the leaves are speckled or turning yellow, and the plant looks like it’s shedding some leaves.

That’s why you’re here. You are worried those tiny flies might be affecting your plants, so you searched for “white flies,” and you found this article. Well, you are in the right place. Welcome!

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

Whiteflies are notorious pests, with a taste for a wide variety of plants including common vegetables and ornamentals.

We’ve got everything you need to know about these insects covered below, from identification and biology to the control options that are available to you.

Here’s what we’ll cover:

What You’ll Learn

What Are Whiteflies?

Whiteflies are not true flies. Instead, they are in the Hemiptera order, related to aphids and mealybugs, and make up the Aleyrodidae family. There are 1,500 known species worldwide.

Thanks to the adults’ tendency to flutter up in a white cloud when disturbed, these are some of the more easily noticed and recognized pests out there.

Pests in the immature and adult stages are sap suckers, using their needle-like mouthparts to pierce plant tissue and sip the plants’ food, including the sugary products of photosynthesis, from the phloem.

They prefer to feed and reproduce on the underside of leaves.

Feeding causes speckling, bleached and yellow leaves, and eventually necrosis. This damage reduces plants’ photosynthetic capacity, weakening them and reducing yields.

Certain species can also transmit viruses, which cause a myriad of plant diseases.

Diseases vectored by whiteflies include begomoviruses, which affect a wide variety of important crops worldwide, such as tomatoes, cassava, soybeans, and cotton, and a variety of other virus types. Leaf curl viruses and mosaic viruses are common.

As they feed, these bugs secrete honeydew, which grows ugly sooty mold and attracts ants. The ants interfere with beneficial insects that are trying to prey on or parasitize the whiteflies.

Whiteflies attack vegetables and ornamentals, and tend to be a problem especially when the weather is warm.

Low numbers are not usually damaging, unless they are carrying diseases, but populations can grow rapidly, and high populations are notoriously hard to control.

Outbreaks are often related to disruptions in natural biological controls, whether because of ants or pesticides, warm weather, or dusty conditions.

Capable of causing significant yield losses in crops, these insects are no joke! The adults themselves don’t usually cause a great deal of damage, unless they are transmitting disease.

Rather, it is the nymphs that cause most of the damage.

Identification

Most species are hard to tell apart, even with a hand lens. Often, identifying the species involves taking a close look at the last instar (often called the pupa), or examining the pupal case which is left behind after the adult hatches.

The tiny adults have yellow toned bodies that are one-sixteenth of an inch long, four white wings, and a white, waxy appearance. Sometimes species similar in appearance can be distinguishable by the angle of their wings.

Nymphs can look like scales or mealybugs: flat, round to oval shaped, and waxy.

Eggs are white, oblong, and laid on leaf undersides. Often, the eggs are arranged in a semicircle.

Why? The female doesn’t bother to stop feeding while she lays, and will instead pivot around her feeding site.

Common species found on garden plants have wide host ranges which include both weeds and crops.

The silverleaf whitefly (Bemisia argentifolii) is perhaps the most common, affecting over 500 species of plants including roses, petunias, poinsettias, squash, broccoli, cauliflower, carrots, and more.

On certain crops, it can cause specific symptoms, such as light root of carrots and irregular ripening in tomatoes.

The greenhouse whitefly (Trialeurodes vaporariorum) is also notoriously common and has a broad host range of herbaceous plants, including tomatoes, coleus, and fuchsia, among many others.

These two species have overlapping host ranges and will infest the same crop, sometimes at the same time. To tell the difference between them, use a 10X or 40X hand lens to examine the wing angle.

T. vaporariorum’s wings are flat in relation to the leaf surface, while the wings of B. argentifolii are held at a 45 degree angle to the leaf surface.

The sweet potato, tobacco, or cotton type (B. tabaci) has a large host range as well, and can cause serious losses in certain crops, especially since it is the most prevalent virus vectoring whitefly species in the world.

Other species include the banded-winged whitefly (T. abutilonea), which prefers poinsettias, geraniums, and petunias, and the citrus whitefly (Dialeurodes citri) which attacks citrus trees and some ornamentals like gardenias and lilacs.

Biology and Life Cycle

Females lay eggs in the characteristic half-circle shape described above on the undersides of leaves, often choosing younger leaves to oviposit on.

Each female can live for one and a half months, and lay over 200 eggs. Mating is not necessary, as unmated females can lay haploid eggs, which will all hatch as males.

After hatching, the insect goes through four nymphal stages known as instars.

The first of these is known as a crawler. It has six legs and will move around for several hours after hatching before settling down to feed. Often it will only move a few millimeters from its hatching site.

The next two instars are immobile and this period is spent feeding.

The fourth instar is sometimes called the pupa, even though whiteflies don’t go through a complete metamorphosis.

It takes 10 to 12 days for these pests to go from the crawler to pupa phases at temperatures of 65 to 75°F.

The entire life cycle can take as little as two and a half to three weeks during warm periods, and up to six months during the winter.

Within one population, generations often overlap, and you could find representatives of each stage on one plant!

Monitoring

Unfortunately, you can’t rely on the development of symptoms to give you a heads up that something is sucking on your plants. Infested leaves might not show any signs of damage until they turn yellow and drop off the plant.

It isn’t hard to notice the adults, though, since they fly up in a cloud whenever they are disturbed.

Commercial growers use yellow sticky cards to monitor adult population levels. While this can be useful, it is not always accurate. Populations can hide out right beside a sticky card if their plant isn’t disturbed, giving you a false sense of ease.

The eggs and nymphs are hard to spot, and require close inspection of the undersides of leaves with a hand lens.

To keep on top of populations, scout a few plants in several areas of your garden for eggs, nymphs, and adults.

Monitoring is crucial because once populations become established, it is difficult to achieve control.

Organic Control Methods

Adults are hard to control because they fly up when disturbed, such as when you touch the plant or begin applying products. Plus, eggs and the fourth instars (pupae) are immune to many pesticides.

To top it all off, whiteflies are talented at developing resistance to pesticides. Thus, prevention techniques and using a wide range of strategies in combination with nature’s gift of natural predators are the keys to achieving and maintaining control.

The integrated pest management (IPM) approach combines methods such as prevention, exclusion, and cultural methods for safe control of many insects and can be highly effective. Learn more about IPM and how to design your own program.

Cultural and Physical Control

Thoroughly check all new plants for eggs and nymphs before introducing them to your garden.

While doing monitoring checks, remove leaves with eggs on them and destroy them. Plus, remove and destroy any heavily infested plants if possible.

Use a strong jet of water to wash the plants, which can help dislodge pests in the feeding stages as well as eggs.

Control the ants which protect the whiteflies from predation by applying a sticky substance such as Stiky Stuff Adhesive, available at Arbico Organics, to trees and shrubs near the base of the plants. This will catch them as they try to crawl up to gather honeydew.

Weed control is important, as most whitefly species have several weeds they like to overwinter on and use as alternate hosts.

For example, B. argentifolii has over 30 potential weed hosts including thistles, spurges, and white clover. Controlling these plants around your garden may help to keep pest numbers down.

Drought-stressed plants are more susceptible to attack and damage, so keep your plants well watered and healthy.

But avoid excessive fertilizer applications, especially nitrogen, which increases pest reproduction, improves chances of survival, and stimulates faster development.

Biological Control

Lacewings, predatory insects such as minute pirate bugs (Anthocoridae), big-eyed bugs (Geocoridae), and assassin bugs (Reduviidae), beetles such as Delphastus species, and predatory mites will all target whiteflies.

Attract these good guys into your garden by adding a wide variety of flowering plants, such as yarrow and dill.

Green lacewings can also be purchased and applied. Eggs or larvae are both available at Arbico Organics.

Encarsia formosa is a parasitoid wasp that attacks T. vaporariorum specifically, and will sometimes target B. tabaci, but it doesn’t provide control of other species. Find these wasps available for purchase at Arbico Organics.

Eretmocerus eremicus, a parasitic wasp that targets second instar larvae, is an excellent choice for controlling B. argentifolii and B. tabaci.

It will also provide some control of T. vaporariorum and T. abutilonea. Purchase these from Arbico Organics and use them preventatively.

There are several species of native, predatory Delphastus beetles that control whiteflies, each preferring a certain type, including D. pusillus, D. pallidus, and D. catalinae. D. catalinae adults are available at Arbico Organics.

Amblyseius swirskii, a predatory mite often used to control spider mites and thrips, will also attack these white winged pests. They can eat up to 20 eggs a day! Find these mites at Arbico Organics and either use them preventatively or apply to infested plants.

Products containing Beauveria bassiana, a parasitic fungus, can be applied as biopesticides to control whiteflies, along with a variety of other pests.

Try BioCeres WP or BotaniGard, both of which are available from Arbico Organics.

Intentional biological control is most effective when predators or products are combined. For example, use E. formosa or E. eremicus with applications of B. bassiana and Delphastus species or green lacewing releases.

You can also back up biological control releases with insecticide applications.

Insect growth regulators (IGRs), as described below, can be compatible with beneficials since they only affect immature insects during the molting period.

For example, E. emericus applied on its own may need up to three introductions to achieve control, but this can get expensive. Couple it with an IGR application and only one of each is required for satisfactory results, and the cost is minimized.

Organic Pesticides

Since adults and pupae aren’t susceptible to most pesticides, both organic and chemical pesticides will probably need to be applied weekly for four to five weeks to achieve control, or successfully eliminate all stages.

Some organic pesticides can provide control, but thorough coverage is required.

Azadirachtin is an organic growth disruptor that can be effective against these insects, and you can find products containing this neem tree extract, such as AzaGuard, available at Arbico Organics.

Neem oils, such as this product from Bonide, which you can find at Arbico Organics, can be useful as well.

Or, try horticultural oils such as this product from Monterey, which contains mineral oil. You can find it at Arbico Organics.

Chemical Pesticide Control

Insect growth regulators (IGRs) can be safely used in conjunction with many beneficial predators.

Buprofezin and pyriproxyfen are two examples of IGRs that are considered reduced risk chemicals, meaning they are low-risk to both to humans and wildlife. These products can move translaminarly through the leaves, and affect pests feeding on the undersides.

Carbamates, organophosphates, and pyrethroids will provide a quick knockdown when there are large populations, but as these options are not selective, they will also kill beneficials.

Systemic insecticides, those that are transported throughout the plant, are more effective than contact insecticides. But many of these, including neonicotinoids, can have negative effects on beneficial insects.

Clouds of Trouble Brewing

The last thing you want to see emerging from your beautiful vegetable or flower patch is a cloud of white flying insects.

And the damage they and their children cause is even worse.

Not only do they leave speckled, yellowed, or shed leaves in their wake, they can vector some serious viral diseases as well.

Luckily, now you know how to work with all the good guys from nature and a variety of cultural methods, along with an occasional spritz of organic pesticides in extreme cases, to keep these plant menaces under control.

Tell us about your experiences with whiteflies, which of your plants they seem to prefer, and your strategies in the comments below!

And for more information about pests in the garden, have a look at these guides next: