Vaccinium macrocarpon

Have you ever thought about growing your own cranberries, so you can always have a fresh supply for juices, smoothies, pies, and of course, your holiday table?

I love using fresh cranberries in baking. Nothing beats fresh cranberry bread and muffins straight out of the oven.

And dried cranberries are a staple in my homemade breakfast granola mix.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

Instead of buying jars of mass-produced sauce as an accompaniment to a holiday turkey, roasted cranberries are a staple on my Christmas table, but more about that later.

So it’s a shame that many people think cranberries are too difficult to grow at home, or are under the impression that they only grow in bogs.

While it is true that they are commercially grown in natural or manmade bogs, and you may have seen pictures of farmers wearing waders, up to their knees in water, this is not how they are grown – only a commercial method of “wet” harvesting.

It’s actually quite easy to grow cranberry plants in your garden – provided you can meet three very important conditions for their growth:

Acidic soil, adequate moisture, and 1000-2500 chill hours of cool temperatures between 32 and 45°F.

Interested? Let’s get started!

What You’ll Learn

Cultivation and History

Cranberries belong to the subgenus Oxycoccus of the genus Vaccinium and are members of the Ericaceae, or heath family, which includes blueberries.

The species of cranberry native to North America is V. macrocarpon, aka large, true, or American cranberry, while the variety commonly grown in Europe is V. oxycoccus.

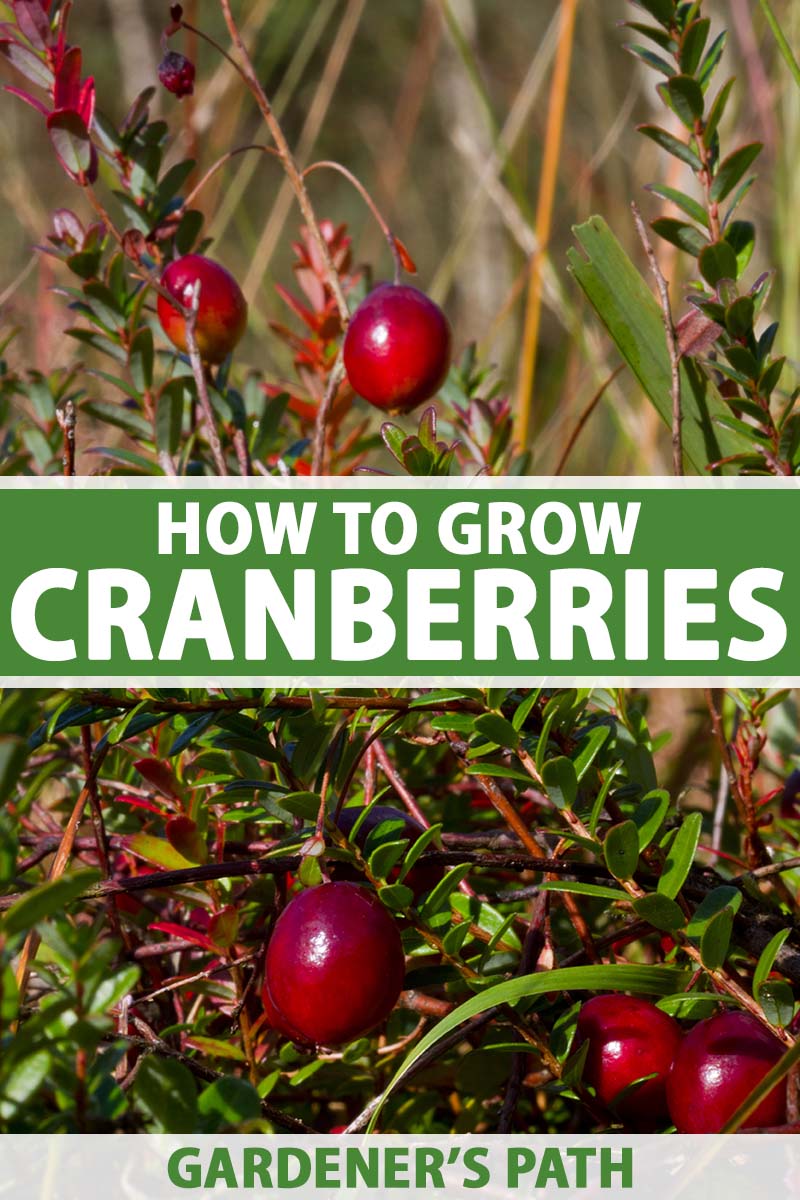

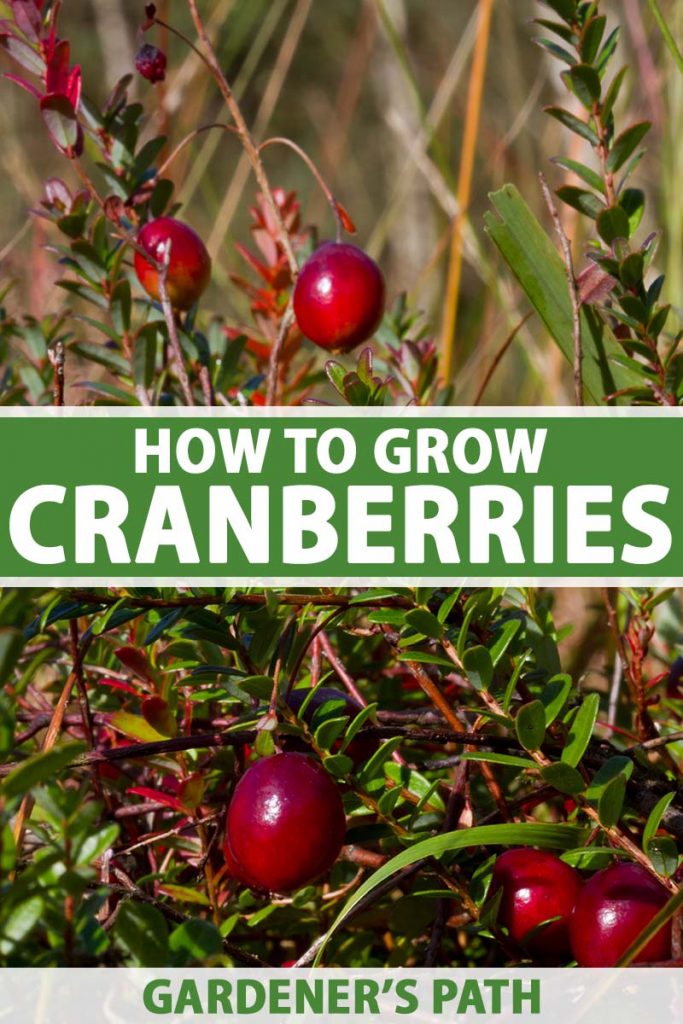

The North American variety is suitable for cultivation in USDA Hardiness Zones 2-7. It’s a woody, low-growing, perennial plant with rhizomatous roots, which grows runners of up to six feet long, and can be planted in beds or pots.

Most of the flowers and fruit are borne on “uprights,” stems with a vertical growth habit up to 18 inches tall, that sprout from buds on the runners.

Of course, cranberries have a rich history in North America, long before settlers decided to cultivate them commercially.

Native peoples, including the Algonquin, Cree, and Chippewa collected wild cranberries to use as food, medicine, and dye. The Algonquin called them sassamanash, which means “sour berries.”

They didn’t just collect the berries, either. The leaves were used to make a refreshing tea, and according to an article by Sarah Whitman-Salkin in the National Geographic Magazine, were even used as a tobacco substitute by the Inuktitut.

Iroquois and Chippewa used the fruit for a variety of medicinal purposes.

The fruit was traditionally used in pemmican, a mixture of dried meat, fat, and berries, made into small cakes. Pemmican was a nutrient-rich food that would last for several months, ideal for times of food shortage or when traveling – a traditional “energy bar,” perhaps.

If you’re wondering when the ever-popular cranberry sauce first appeared, it was way back in 1663 in the Pilgrim Cookbook.

Today, cranberries are popular all over the world, although 98 percent of the world’s commercially grown cranberries come from the US and Canada.

Despite their extremely tart flavor when eaten raw, they’re a firm favorite in juice, pies, relish, and cakes – and are made much more palatable by the addition of sugar. Dehydrated berries are a tasty snack, equally at home in morning oatmeal or sprinkled over a summer salad.

Cranberry juice is an important ingredient in the much-loved (by me, anyway) cocktail, the Cosmopolitan, and is frequently used in an attempt to relieve the symptoms of UTIs (the juice, not the cocktail!).

Propagation

Although cranberries can be grown from seed, you’ll need some patience as it can take three to five years for a seed-grown plant to produce fruit.

Also, bear in mind that any seed you save from existing plants may not grow true to the parent, as there are a number of different hybrids and cultivated varieties in circulation.

However, you can take cuttings from existing plants to root at home, and in some areas you may find rooted cuttings or nursery starts available from your local garden center for transplanting.

I’ll cover the different propagation methods below:

From Seed

Unless they are labelled as “pre-stratified,” seeds will require a period of cold stratification before sowing. You can do this by placing them in the refrigerator for about three months before sowing indoors.

After they have been cold stratified, you’ll need three- to four-inch pots and some acidic, ericaceous potting mix. Place two seeds in each pot, planted about 1/4 inch deep, and cover lightly. Press the soil down gently and mist with water.

Find a warm place to put the pots – the soil needs to maintain a consistent temperature of 70°F for seeds to germinate. You may consider using a heat mat. Seeds will typically sprout in 3-5 weeks, although it could take longer.

Keep the growing medium evenly moist but not waterlogged, and do not let it dry out.

After germination, thin out the smallest seedling from each pot. Place the pots in a warm but not too hot (60-75°F) location, and water them consistently, as these plants don’t tolerate dry conditions.

For the first year after germination, it’s best to keep the seedlings in their pots, maintain even moisture, and plant out in either the spring or fall.

From Stem Cuttings

A more reliable method of propagating cranberries is via stem cuttings, which take root easily.

Prepare one or more small pots with a well-draining, acidic potting mix, or regular potting soil amended with peat moss or ericaceous compost.

In spring or early summer, take a five- to eight-inch cutting. Remove all but the top four or five leaves, and any flower buds, and dip the cut end into powdered rooting hormone (if desired).

Make a hole in the potting medium and place the cutting about three to four inches deep. Your pots can then be transferred to a warm location with indirect sunlight, such as a windowsill or greenhouse. Maintain even moisture in the soil, and remember: don’t ever let it dry out!

After six to eight weeks, the cutting should take root, and can be transplanted into a larger pot or out into the garden.

From Seedlings and Transplanting

If you’ve bought one- to three-year-old plants, or when your own seedlings are old enough, you can transplant them into their permanent beds.

But before you set them out, you’ll need to do some preparation. As mentioned, cranberry plants require acidic soil that drains well. While they do like a lot of moisture, they do not thrive in oversaturated conditions.

Ideally, soil pH should be 4-5.5, which you can check by conducting a soil test or with a pH meter.

Gain Express Soil pH and Moisture Meter

You can find a soil pH and moisture meter available via Amazon.

If the soil isn’t acidic enough, you can add peat moss, an ericaceous compost mix, or a soil acidifier such as sulfur, to the top few inches to increase acidity.

You can find a mix of elemental sulfur and gypsum from Espoma, available via Amazon, that is suitable for organic gardens.

Follow the package instructions and remember to retest your soil pH after amendments.

If your soil is heavy, you can also add sand to improve drainage.

In cooler areas, the best time to set them out is in the spring, after all risk of frost has passed. If you live somewhere milder, where winters are warmer, you can safely plant them in autumn.

You’ll need a sunny spot to place them, though in warmer climates they can tolerate a little afternoon shade.

Remove all weeds and grass from the planting location, as they can choke young cranberry plants.

At this stage you can mix a little bone meal into the soil, according to package instructions.

Dig a hole that is a little larger than the size of the container the transplant was growing in, allowing two feet between each plant to provide enough room for the runners to spread out.

Water the hole before you place the plant in, and then gently backfill with soil and water again.

For planting in pots, you’ll need a 12 to 18-inch wide container, eight inches deep.

Cranberry plants don’t have deep roots, typically only four to six inches, but the runners do need space to spread. If you do choose to grow your plants in containers, you’ll have to be extra vigilant about watering, as pots dry out much quicker than garden soil.

You can learn more about how to grow cranberries in containers in our guide. (coming soon!)

How to Grow

Once your cranberry plants have been transplanted, you’ll find they are easy to maintain.

The main care they require is maintaining adequate, even moisture – one inch of water per week is usually sufficient, depending on weather conditions. Be extra vigilant during dry spells or heatwaves.

When you irrigate your crops, keep in mind that a lot of municipal water is alkaline, and can affect the pH of the soil. Where possible, you should use rain water or filtered water.

You need to keep the growing area weed-free, as grass or other unwanted plants will compete for water and nutrients. Hand weed the area regularly, and take care not to disturb the soil around the shallow roots.

You can apply a layer of mulch around young plants to aid in moisture retention and help to suppress weeds.

As mentioned, your plants need 1000-2500 chill hours in order to fruit and produce a harvest. During the winter months, protect your plants with a layer of organic mulch – pine boughs work well as they also add acid to the soil.

Cranberries need very little fertilizer. If you are concerned that your soil is lacking in nutrients, you can fertilize in spring with a 2-4-2 (NPK) fish emulsion.

In spring, you can remove any dead or damaged stems, and prune the runners lightly, taking a few inches off the ends, to encourage the growth of the flower-bearing uprights and keep the plants from spreading too far.

Growing Tips

- Make sure your soil is acidic.

- Plant in a full sun location, with some afternoon shade in hot areas.

- Protect young plants during winter with mulch.

Cultivars to Select

Over 100 North American cranberry cultivars are available on the market today. Some of these are only available to commercial growers, but there’s still a good selection for the home gardener.

You can learn more about the different cranberry varieties in our guide.

Here are three options for you to consider:

Early Black

‘Early Black’ is a vigorous grower, producing dark red berries that, as the name suggests, ripen early – typically from late August in most locales. The fruit is relatively sweet, when compared to other varieties.

It’s not fussy about soil, exhibits some resistance to false bloom, and is frost-tolerant.

In cold weather, the foliage turns an unusual shade of reddish-bronze.

Pilgrim

‘Pilgrim’ is a popular hybrid cross of ‘McFarlin’ and ‘Prolific.’ Attractive, dark pink flowers give way to an abundance of shiny, plump, dark red berries, which are especially juicy and delicious.

This cultivar is moderately resistant to false blossom.

You can find plants in 3.25-inch containers available via Amazon.

Stevens

‘Stevens’ is a popular hybrid variety producing an abundance of deep red, juicy fruits. A cross between ‘McFarlin’ and ‘Potter,’ plants are moderately resistant to false blossom.

You can find plants available at Fast Growing Trees in two-quart and two-gallon containers.

Managing Pests and Disease

Cranberry plants grown at home don’t typically suffer from many pests and disease issues, but there are a few you should be aware of.

Insects

In addition to the usual garden annoyances such as aphids, whiteflies, and thrips, keep a close eye out for these critters, which can ruin your cranberry vines:

Cranberry Fruitworms

The cranberry fruitworm (Acrobasis vaccinii) is the larvae of a moth belonging to the Pyralidae family.

The adults lay their eggs on unripe fruit and when they hatch, the larvae burrow into berries to feed on the soft pulp. These small caterpillars are green, with brown stripes along their backs. Fully grown, they are up to half an inch long.

Feeding larvae causes the fruit to turn red prematurely, and then to dry up and shrivel. You may notice entry and exit holes on each berry, covered with a fine webbing.

These pests have a voracious appetite and will move from berry to berry, munching their way through your crop.

Cranberry fruitworms can be difficult to manage, because the eggs are so tiny, they can only be seen under a microscope. The adult moths tend to be active overnight, and at dawn and dusk.

Keep the area around your plants free from weeds and plant debris, and consider using pheromone traps to monitor the presence of adult moths.

If you find evidence of the adults, you can treat your plants preventatively with bio-pesticides such as spinosad or neem oil. These will need to be applied before the bloom phase.

Ladybugs are one of the fruitworm’s main predators, so encourage these and other beneficial predators to take up residence in your garden.

You can also purchase ladybugs to release into your garden. Be sure to choose those that have been raised in captivity rather than ladybugs that have been collected from the wild and shipped elsewhere.

Cranberry Weevils

Cranberry weevils, Anthonomus musculus, are tiny beetles that attack a variety of plants, including blueberries.

These insidious beetles lay their eggs in flower buds, and when they hatch the larvae munch away on the developing blossoms, preventing them from producing fruit. The flower bud will often change color and appear orange as a result of the damage.

The adult beetles will eat new leaves, unopened blossoms, and the immature berries.

Evidence of adults feeding can include black spots on the undersides of the leaves and runners, which can often look similar to frost damage.

These pests are a major threat to commercial cranberry operations, particularly in Massachusetts. They are difficult to control and commercial growers use a variety of insecticides not available to home gardeners.

Yellow sticky traps, available at Arbico Organics, placed in and around the planting area can help to reduce adult populations.

You can learn more about common cranberry pests in our guide (coming soon!)

Disease

There are a few diseases that can affect cranberry plants, but these are typically a problem for large-scale growers.

False Blossom

False blossom is caused by a virus-like phytoplasma, spread by the blunt-nosed grasshopper (Limotettix vaccinii) resulting in abnormal growth in flowers followed by a failure to set fruit.

Infected plants may form a “witches broom” appearance, with stems that turn a reddish-brown color.

There is no treatment except to get rid of the diseased vines. Many modern hybrid varieties are resistant to false blossom.

Leaf Spot

There are two types of fungal leaf spot diseases that commonly affect cranberry plants. Typically these are not fatal, and are easy to manage.

Red leaf spot is caused by Exobasidium rostrupii, and shows up as bright red spots on the top surface of the leaves, followed by a white fungal growth on the undersides, not dissimilar in appearance to powdery mildew.

Protoventuria leaf spot is caused by Protoventuria myrtilli, and is sometimes referred to as gibbera leaf spot. Small dark red spots appear on the upper surface of the leaves, the foliage eventually turns chloritic, and tiny black fruiting bodies appear.

Moist, damp conditions favor the outbreak of fungal infections, which is why it is very important that your soil is well draining.

Unless the outbreak is extensive, you can usually treat either of these infections by trimming off affected plant tissue (and dispose of the debris in the trash, not your compost pile), and irrigating in the morning, so the foliage has a chance to dry out over the course of the day, to avoid a build up of humidity.

Rose Bloom

Rose bloom is a fungal infection caused by Exobasidium vaccinii, which attacks new shoot growth, causing the branches to thicken and enlarge, producing light pink leaves that look a bit like small roses.

Sometimes the blossoms and fruits can become infected as well.

You can treat rose blossom with a broad spectrum fungicide.

Apply according to package instructions. You can learn more about the safe application of chemicals in our guide.

You’ll find more information about cranberry diseases in this guide. (coming soon!)

Harvesting

Commercial cranberry growers have two methods of harvest, depending on what the fruit will be used for: wet harvesting and dry harvesting.

Wet harvesting methods are typically used for fruit that are destined to be made into juices, sauces, or as ingredients in processed foods. Dry methods are used for those that are going to be sold fresh, for cooking and baking.

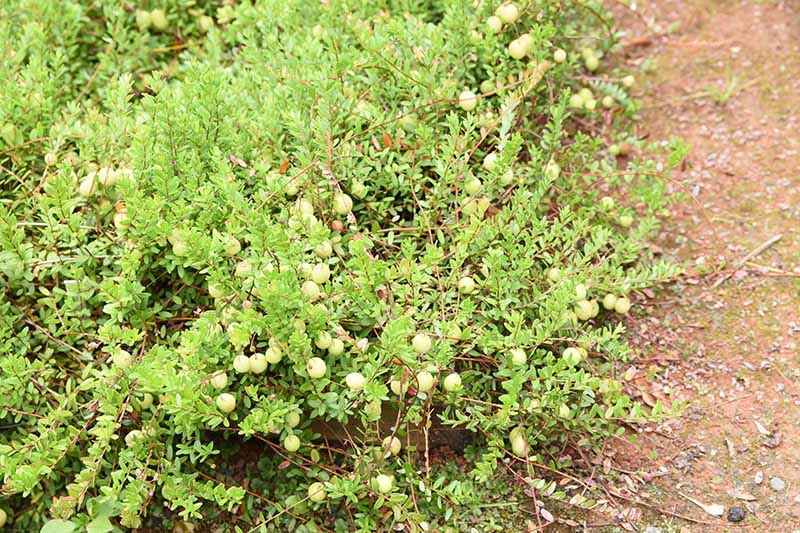

You’ll know your cranberries are ready for harvesting when they’re an even, deep red color, slightly firm to the touch. This is typically between the beginning of September to the end of November, depending on the variety you are growing.

You can also try the bounce test – cranberries have pockets of air in them, which means they are springy. If a cranberry bounces when you drop it, that’s a sign that it’s perfectly ripe. Unripe cranberries will not continue to ripen after they are picked from the plant.

If you can bear to wait, a light frost or two will generally sweeten the berries. Harvesting is a simple process: Pick the berries gently by hand, and throw away any which are damaged, bruised, or very soft.

You can learn more about how to harvest cranberries in our guide. (coming soon!)

Preserving

Preserving your precious harvest means you’ll always have an ample supply at hand to make a delicious sauce or pie.

Always wash cranberries thoroughly before taking any steps to preserve them. The fresh fruits will last three to four weeks in the refrigerator.

You can freeze your crop straight after harvest. They’ll keep for 10-12 months in sealed freezer bags or an airtight plastic box. To do this, spread them out on a baking sheet and place them in the freezer for a few hours, then transfer to zip top bags or your container of choice.

You don’t even need to defrost them before using them in baking or cooking – just take them out of the freezer and add them to your recipe as you would fresh berries.

I prefer using frozen cranberries when baking, as they hold their shape better and the color doesn’t “bleed” into the finished product as much as it does with fresh fruits.

Dried cranberries are one of my favorite additions to morning muesli and winter oatmeal. Drying them is pretty easy, and they’ll keep for a month or two.

Before you throw them in the dehydrator, you can choose to sweeten them. I don’t do this, because I like the slightly tart flavor.

To sweeten them, place them in a pot and pour boiling water over the top, let them sit for a minute, and then drain and wrap them in paper towels to dry off.

Then, make a simple syrup of one part sugar to two parts water, and add this to a bowl along with the blanched fruit. Let it sit for five to ten minutes, or longer if you prefer.

Drain off the simple syrup, pat the fruit dry with a paper towel, and place them in a single layer on a baking sheet in the oven, on its lowest setting, for 8-12 hours, checking regularly.

You can also use a dehydrator. If you don’t have a dehydrator, why not check out this review from our sister site, Foodal, which will also give you top tips for dehydrating a variety of produce.

Recipes and Cooking Ideas

I kid you not, there are so many different ways you can use your homegrown crop.

Remember I mentioned roasted cranberries as an alternative to the store-bought sauce?

This is my favorite accompaniment to a Christmas turkey, but I also enjoy them with a pork roast. Check out the recipe, with step-by-step instructions, on our sister site, Foodal.

Or for an interesting twist on the traditional cranberry sauce, head to Foodal for the recipe.

While we’re on the topic of the holidays, you can also add them to a homemade stollen, a traditional bread from Germany. This recipe is also from Foodal.

And if you need some inspiration for a healthy side dish, have a gander at this butternut squash and cranberry quinoa recipe, over at Foodal.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Woody, perennial berry plant | Water Needs: | Moderate |

| Native to: | North America | Maintenance: | Low |

| Hardiness (USDA Zone): | 2-7 | Tolerance: | Frost, flooding |

| Season: | April - November | Soil Type: | Loose, rich |

| Exposure: | Full sun | Soil pH: | 4.0-4.4 (acidic) |

| Time to Maturity: | 3 years | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Spacing: | 2 square feet per plant | Companion Planting: | Azaleas, blueberries, lingonberries, rhododendrons, and other ericaceous plants |

| Planting Depth: | Same as root ball (transplants), 1/4 inch (seeds) | Family: | Ericaceae |

| Height: | Up to 18 inches | Genus: | Vaccinium |

| Spread: | 1-6 feet | Species: | macrocarpon |

| Common Pests: | Aphids, blackheaded fireworms, caterpillars, cranberry blossomworms, cranberry tipworms, cranberry weevils, leafhoppers, mirids, spotted fireworms | Common Diseases: | Cottonball, false blossom disease, fruit rot, leaf spot, rose bloom, stem gall, twig blight |

Crank up the Cranberry Goodness

There are so many delicious ways to use these healthy, nutritious berries.

And as long as you can fulfill those three conditions to keep them happy – chill hours, acidic soil, and plenty of water – you could soon have your own cranberry plants, with berries ready for harvest in time for next Thanksgiving.

Have you tried growing your own cranberries? If not, why? Let us know in the comments section below.

And for more information about growing fruit in your garden, check out these handy growing guides next:

- The Ultimate Guide To Growing Strawberries at Home

- How to Grow Cantaloupe in the Garden

- How to Grow Raspberries: Enjoy Berries for Years to Come

© Ask the Experts, LLC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. See our TOS for more details. Revised and expanded from an original draft by Alexa Ward. Product photos via Arbico Organics, Bonide, Fast Growing Trees, and Hirt’s Gardens. Uncredited photos: Shutterstock.

wow information coming out of my ears.

thanks for it though