Helleborus orientalis

If you’re tired of looking out the window at a dormant winter landscape, have I got a plant for you! It’s Helleborus orientalis, aka Lenten rose, or simply, hellebore.

Helleborus is a genus in the Ranunculaceae, or buttercup family that includes anemones and delphiniums.

While the rest of the garden sleeps and chill winds blow, this pugnacious evergreen perennial raises stalwart stems into the frosty air, often blooming as early as January, and continuing well into spring.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

In this article, I’ll cover all you need to know to cultivate hellebores in your garden.

Here’s what’s to come:

What You’ll Learn

Cultivation and History

Hybrids of the wild Lenten rose are readily available for home gardeners in USDA Hardiness Zones 4-9. You’ll find them under the name Helleborus x hybridus, which we’ll talk about in a little bit.

Lenten roses are acaulescent, which means each stem rises directly from the rhizomatous root system, to form clumps that may reach two feet tall and wide.

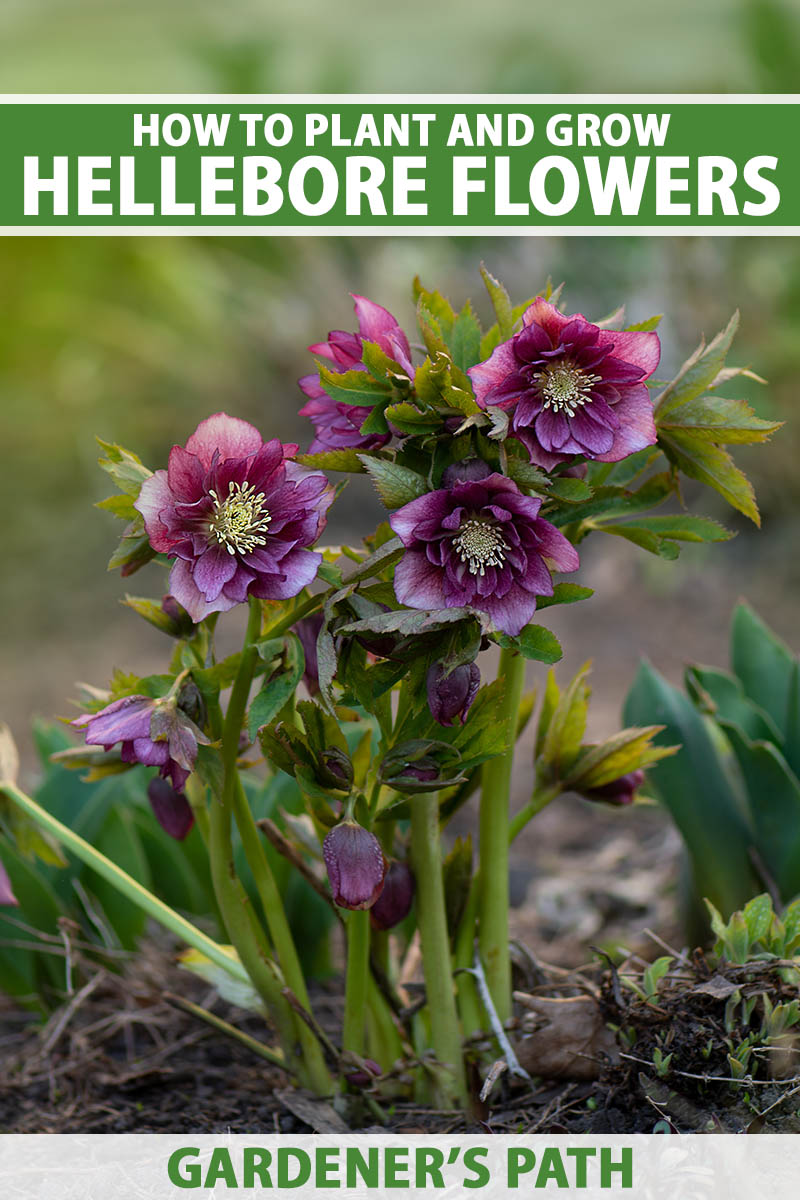

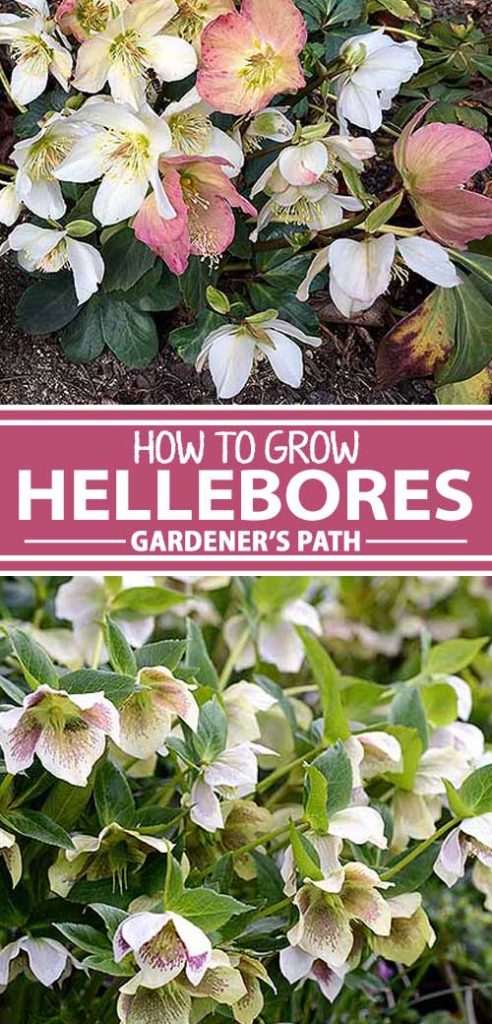

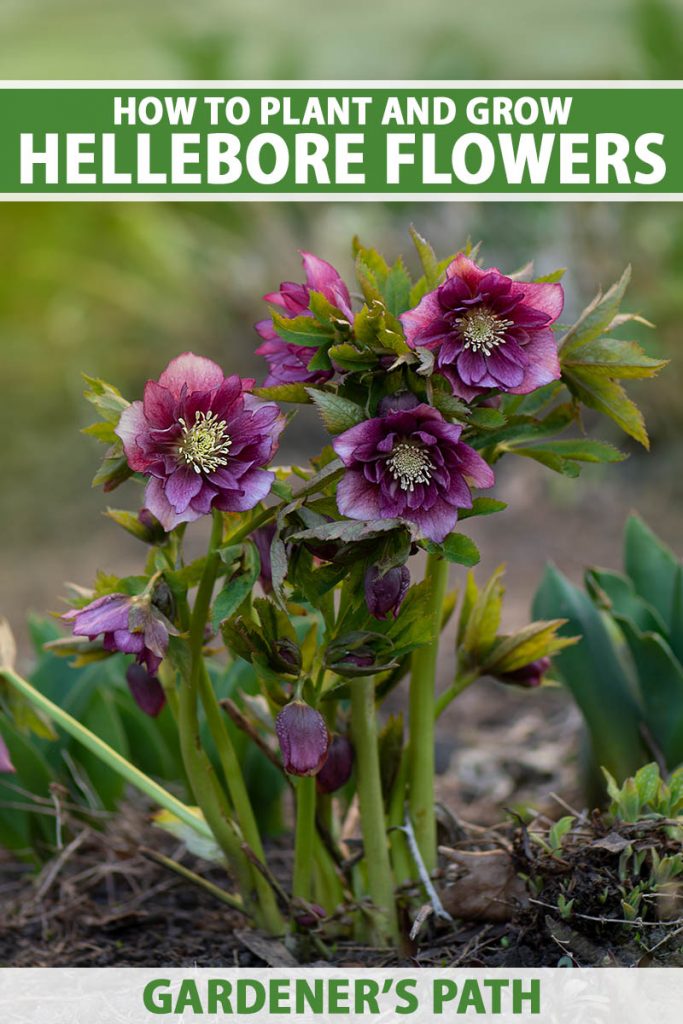

Downward-facing cup-shaped flowers consist of petal-like sepals surrounding an intricately detailed inner flower called a “nectary.”

Sepal hues range from shades of green and yellow to pink and red. Variations such as contrasting spotting, veining, and “picotee” edging, as well as semi-double and double sepals, multiply the possibilities in an already extensive color palette.

Foliage consists of glossy dark green multi-lobed leaves with a serrated edge and leathery texture.

Hellebores require moist, loamy soil that is well-drained. They thrive in exposed locations in the winter, but when summer heat arrives, they are vulnerable.

Plant in the partial to full shade of a deciduous tree (one that drops its leaves), so that they have protection from the summer sun.

I lost a hellebore once to intense summer heat. I had placed it near a spruce tree, thinking that it would provide appropriate shade. No such luck.

A Note of Caution:

It is important to note that like many ornamentals, hellebores are toxic to people and pets. In addition, skin contact may cause irritation, so gardening gloves are a must when you are handling these plants.

There are currently 20 known species in the Helleborus genus, and most of these are native to the limestone-rich regions of the Mediterranean, and in particular the Balkan mountains. One species, H. thibetanus, is native to China.

From the wild, this plant made its way into the gardens of European herbalists, before becoming an ornamental specimen prized by master gardeners, and finally a home garden favorite.

The name is thought to be derived from the Greek words helein, meaning kill, and bora, or food. This is a perfect representation of its dual nature as both a beneficial medicament in appropriate quantities and a deadly toxin when administered in excess.

Hellebore’s history is the stuff of legends, loaded with intrigue and superstition.

In Greek mythology, it is referenced as a cure for madness, and in the First Sacred War – 595 to 585 BC – it is believed to have been used to poison a water supply, crippling the inhabitants of Kirrha with gastrointestinal distress so dire that they could not defend their city.

By the 1500s, its powerful purgative qualities were relied upon regularly to cleanse the minds and bodies of both people and animals.

At one point, people believed that a dusting of powdered hellebore could render them invisible, but perhaps these were the same folks who were being treated for madness…

By the mid-1850s, the hybridization of various species as ornamental specimens was well underway across Europe.

Evidence of the arrival of these plants in America is sparse, with speculation that it was likely introduced for medicinal purposes.

However, by the 1700s, John Bartram, a noted Philadelphia, Pennsylvania botanist, made references to the plant, and by the early 1800s, dried, powdered root was available to purchase for use as both a deworming medicine and an insecticide.

It wasn’t until the 19th Century that hellebores made their way into American gardens, courtesy of Cornell University botanist Liberty Hyde Baily, whose Cyclopedia of American Horticulture described eight species well suited to home gardening.

By the 20th Century, other noteworthy Philadelphia region gardens, including the Scott Arboretum at Swarthmore College, and Winterthur, the DuPont estate, had impressive ornamental collections, and the race to create and collect even more hybrid varieties was on.

Because of their ease of cultivation, early bloom time, and longevity, today’s hellebores are in great demand.

Let’s talk about how to grow your own.

Propagation

Hellebores can be started from seed, by division, and by micropropagation – the latter is beyond the scope of this article.

Alternatively, you can purchase potted plants or bare roots from your local garden center or nursery for transplant.

For an in depth look at how to propagate hellebores, check out our guide.

From Seed

Hellebores are self-sowing, but keep in mind that seeds from hybrid plants generate variable characteristics, and will typically not replicate those of the parent plant.

You may let seeds drop naturally from existing plants and transplant seedlings to desired locations. Seeds that drop into the root crown of the parent plant should always be relocated.

Different colored self-sown seedlings may sprout near one another and give the appearance of one plant with two different color blossoms for added interest.

Alternatively, you can harvest seeds in early summer, after the plants have finished flowering. Some growers fasten small mesh bags around wilted flowers to catch the seeds as pods open. When they are black, sow them immediately.

Learn more about how to harvest hellebore seeds in our guide.

You may also purchase ungerminated seeds and germinated seed plugs to get started, if you have no plants from which to collect them.

We cover all the details about how to grow hellebores from seed in this guide.

By Division

Another way to start a new plant is by digging up an existing plant, and cutting through the rhizome to make one or more separate sections that can be planted elsewhere.

You can divide established plants in late winter or early fall.

Learn how to divide hellebores in our guide.

Transplanting

You can’t go wrong in terms of timing with Lenten rose, because plants are typically available for purchase when the time is right for planting.

If you order from catalogs, delivery is generally timed to suit your growing zone. Mature potted plants, seedlings, and plugs may be put into the ground from March through August.

To prepare the soil for planting, remove grass, weeds, and debris. Work the soil to a friable (crumbly) consistency to a depth of at least six inches. You can amend with some compost or worm castings, but do not apply fertilizer at planting time.

Mound the soil up for each plant to promote drainage and make the nodding flowers a little easier to see.

For a mature potted plant, take note of its depth in the potting medium. You want to plant it at the same depth in your mounded soil. The root crown needs to be a bit above the soil line to prevent rotting.

Remove the plant from its pot. If the roots are tightly bound, gently tease them apart. Brush off the potting medium and place your transplant into the soil, spreading the roots out and nestling the plant in securely. Tamp the soil down, water, and tamp again to remove air pockets.

In addition to transplanting potted plants, you may purchase plugs containing germinated seeds. Be sure to plant the top of the plugs level with the top of the soil in your mounds.

How to Grow

Hellebores require loamy soil that is moist but drains well, with an ideal pH of 7.0-8.0. You may want to conduct a soil test and amend according to the recommendations.

They also do best planted under deciduous trees that provide at least partial shade in summer months. You need to avoid placements that expose plants to strong, drying winds.

Fertilization is not necessary, simply maintain the loamy soil, amending it each spring with rich organic material to provide a fertile growing medium.

New plants should be provided with about an inch of water per week in the absence of rain. You want the soil to maintain even moisture, but not become oversaturated. Once established, additional water is only necessary during dry spells.

Once your plants are in the ground, you’ll need to be patient. Blooming potted plants should bloom again the following winter or spring. Seedlings and seeds need to reach maturity before flowering, and typically won’t bloom for two to three years.

Oh, but it’s worth the wait!

Hellebores are long-lived, and each year they get bigger and produce more flowers. You can expect at least 10 productive years for your investment, given proper soil and moisture, and a hospitable location.

Growing Tips

To summarize, keep the following in mind when planting:

- Choose a location with summer shade.

- Mound the soil and keep the plant crown slightly above ground to promote drainage and prevent rotting.

- Plant in loamy, well-draining soil, with yearly additions of organic matter.

Pruning and Maintenance

As mentioned, H. orientalis may be expected to live for approximately 10 years in the right growing conditions.

Keep the garden weeded to deter pests and inhibit disease. Snip off spent flower stems at their base to promote foliar growth post-bloom.

If you want to divide plants, do so in late winter or early fall. This is not a necessity, unless clumps don’t have room to naturalize. The disruption causes stress that may render plants vulnerable to pests and disease until they become established.

When you divide, plants may wilt temporarily. If you didn’t already do it in the spring, pamper them by adding compost, or other nutrient-rich organic matter to the soil, and maintain even moisture until they perk up.

Late fall is the time to prune the old foliage to the ground to make way for next spring’s new growth.

Some folks leave the foliage in place, because it is evergreen, but in locales with harsh winters, the big old leaves often end up floppy and brown, and spoil the appearance of spring’s new blossoms.

In addition, old foliage may harbor pests and diseases that winter over, so it may be wise to cut the stems back to the ground.

After the growing season draws to a close in late fall, you can apply a layer of mulch for added warmth and retention of winter moisture. Plants that are not bone dry usually fare better in terms of retaining color and resisting wind damage.

Cultivars to Select

Now that you know all about this ornamental perennial, let’s take a quick look at some cultivars for your garden.

We know that the species Lenten rose is H. orientalis. However, the ones we find for sale are usually H. x hybridus.

Hmm… sounds like a word you’d use when you’re not sure what the Latin name is, doesn’t it?

Why is it so… generic?

When we purchase a plant that is native to another country, we are often not purchasing a true species, but rather a hybrid cultivar that has been bred for optimal color and performance in the US.

Hellebores are fascinating because even in their native land, a single species may exhibit a variety of different characteristics. When breeders cross these already variable natives with other true species or hybrids, the result is a dazzling array of options.

You can learn more about the different types of hellebores in our guide.

Pots with plants in bloom are the most expensive. They’ve spent at least three years or so in a nursery, and you’re going to pay for all that attention. However, while they are expensive, this is a sure way to know exactly what the flowers and foliage will look like.

You may also find mature plants that aren’t blooming, in which case you take a gamble on color, but may get a break in price.

Potted seedlings are another option. Again, the less nursery time and the less color certainty, the better the price, in most cases.

Here are a few of my favorite cultivars to get started:

Onyx Odyssey

Double-flowered ‘Onyx Odyssey’ is a standout in the late winter garden. Imagine the contrast between a light coating of white snow and the deep purple-black blooms.

You can plant in a swath with lighter colors for contrast.

Find potted plants available at Burpee.

Painted Bunting

If dark-and-moody isn’t your style, try ‘Painted Bunting,’ with its single blooms featuring creamy white sepals and deep red throats and veining.

Plant together with ‘Onyx Odyssey’ for a dramatic light-and-dark display.

You can find potted plants available at Burpee.

Wedding Party Bridesmaid

‘Wedding Party Bridesmaid’ is a standout cultivar that features double flowers in white with dark pink picotee edges and veining.

Find potted plants available at Burpee.

Managing Pests and Disease

Hellebores are generally healthy, with few issues, especially when they are grown in organically-rich soil and a full to part-shade location.

However, sometimes plants are stressed by placements that are too sunny, causing dehydration which may present as brown leaves and drying roots.

Or, perhaps the garden is full of weeds and there is competition for water, and habitat for insects that carry disease.

One pest that may take advantage of a weak plant is the aphid.

There are numerous species of these sap-sucking insects that leave a sticky trail of shiny “honeydew” as it feeds on and destroys plant tissue.

Address it by using clean pruners to snip off and discard affected foliage – such as misshapen or discolored leaves – discard the plant material in the trash, and sanitize the pruners.

Follow with an application of neem oil or insecticidal soap. Repeated applications may be needed.

Read more about identifying and controlling hellebore pests here.

A common disease you may encounter is leaf spot. This is a fungal infection, caused by Microsphaeropsis hellebori that is easily identified by the brown patches it causes on foliage that eventually fall right out of the plant, leaving holes and weakening stems.

All affected foliage must be pruned off and discarded in the trash with pruners that are cleaned before and after cutting.

Plants may respond to fungicidal treatment.

Another common ailment is downy mildew. Formerly classified as a fungi, it is actually caused by a similar organism called an oomycete, or water mold, Peronospora pulveracea.

It’s characterized by a furry gray to purplish coating, particularly on the undersides of the foliage. Unchecked, leaves develop patches of dead tissue, curl downward, and die.

Use clean pruners to remove affected foliage and discard it in the trash. Plants may respond favorably to fungicidal treatment.

You can learn more about common hellebore diseases in our guide.

And while the aphid itself is treatable, one particular disease it carries is not.

The most serious threat to hellebores is “Black Death.” Its telltale signs are stunted growth and black streaks. Unfortunately, there is no treatment, and the plant must be removed from the garden.

It is speculated that the culprit, the Helleborus net necrosis virus, is transmitted by aphids.

You can read more about hellebore black death in this guide.

I have not experienced these issues with my hellebores. In addition, while I always use the words “deer resistant” with caution, I will say that the visiting deer have not eaten my plants.

Best Uses

To enjoy hellebores at their best, select locations that are sheltered from the summer sun, and give them room to naturalize.

Consider planting sites that can be comfortably viewed through windows, or near entryways, because when the flowers are in bloom, you may not want to go strolling about the frozen grounds to appreciate them.

If you’re a winter-hardy soul, you may like to scatter plants as destinations for invigorating walks, along wooded paths, beneath deciduous trees and shrubbery, and in the shadow of structures like walls and fences, where they can be discovered and celebrated.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Evergreen flowering perennial | Flower / Foliage Color: | Green, pink, purple, red, white, yellow; dark green |

| Native to: | Mediterranean Europe and China | Maintenance: | Low |

| Hardiness (USDA Zone): | 4-9 | Tolerance: | Deer |

| Bloom Time: | Late winter, early spring | Soil Type: | Organically-rich loam |

| Exposure: | Full to part shade | Soil pH: | 7.0-8.0 |

| Time to Maturity: | 2-3 years (from seed) | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Spacing: | 14-18 inches | Best Uses: | Naturalize, beds, borders, shade gardens, woodland settings |

| Planting Depth: | Crown just above soil | Order: | Ranunculales |

| Height: | 1-2 feet | Family: | Ranunculaceae |

| Spread: | 1-2 feet | Genus: | Helleborus |

| Water Needs: | Moderate | Species: | orientalis, x hybridus |

| Common Pests: | Aphids | Common Diseases: | Black death, black spot, downy mildew, leaf spot |

Hooked on Hellebores

My first experience with hellebores was over 20 years ago, when I discovered them in a gardening journal.

They were still very much in the domain of the horticultural elite at that time, and imported native species were showcased as ornamental specimens in elaborate landscape designs.

Once I fell under the spell of manipulating Mother Nature and growing flowers in winter, I wanted to learn more and sought expert guidance.

I found it in “Hellebores: A Comprehensive Guide” by C. Colston Burrell and Judith Knott Tyler, available on Amazon.

Hellebores: A Comprehensive Guide

The authors and photographer Richard Tyler have years of experience harvesting wild species and creating cultivars for home gardeners, which are sold at Pine Knot Farms in Virginia.

Currently, this is the definitive work on the named hellebore species and their various subspecies.

I hope you’re inspired to give this charming winter wonder a place in your garden.

Their nodding heads seem so demure and fragile, but their existence in a frozen landscape is a daring affront to Nature herself.

Cool, huh?

It’s time to take your garden full circle with bold flowers that bloom in the winter-to-spring transition season.

Are you growing hellebores in your garden? Share your experiences with us in the comments section below and feel free to share a picture!

And for more information on growing hellebores in your garden, check out these guides next:

- 11 of the Best Double Hellebore Varieties for the Late Winter Garden

- The Best Hellebore Planting Companions

- Are Hellebores Toxic to Animals or People?

© Ask the Experts, LLC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. See our TOS for more details. Originally published April 22, 2018. Last updated: January 22, 2021. Product photos via Burpee and Timber Press. Uncredited photos: Shutterstock.

This is a wonderful flower, I like the beautiful flowers. Your information is very useful, the article is very good.

Thank you. We are glad you enjoyed it.

Can you plant winter flowering ones and spring flowering ones together so you have flowers for longer?

Thanks

Hi Katrina –

You may plant different species of hellebores together. Bloom times vary.

Thank you for this very interesting article. I live in Wyoming and I have been seeing hellebores for several years, most of them have been planted in very large pots in front of hotels and businesses in Billings, Montana. I’ve looked in several catalogs at their beautiful colors and varieties and I’m very anxious to try a few. Thank you again for the wonderful information.

Hello Treva –

We’re so happy you enjoyed the article. Hellebores are so much fun! We hope you’ll try a few and share photos with us.

The table about Evergreen flowering perennial was so helpful and easy to see thoroughly. Thank you for all the tips, I’m taking that with me in growing plants!

Can they be used in pots? What size pots would be best?

Hi Jackey –

Yes, you can grow a hellebore in a pot. You can start small and work your way up.

The pot should always be one to two inches wider than the plant itself, to allow for easy watering. Be sure it has a good drainage hole.

Use an organically rich potting medium that is both moisture retentive and well-draining.

To accommodate a mature plant, you’ll need a container with a diameter and width between 18 and 24 inches.

How far apart should the plants be spaced?

Hi Gail, ideally you should space them 12 to 14 inches apart to allow for adequate airflow.

My mum’s hellebore I got her last winter is getting smaller in size rather than bigger and I feel it is in an ideal location in her courtyard garden. How can I get it to grow new foliage?

Hello Christinia –

Trimming off the old leaves at the base of the plant should stimulate the growth of new ones.

I ordered mine through the mail from Amazon. They came green but had no blooms. Planted I know at least 2 years ago and still have yet to bloom any flowers! I have no clue what is going on with mine. So disappointed but hope it’s just my impatient nature and they’ll bloom soon. 🙏🏻 🌸🌷

Hi Chancey –

We are sorry to hear your hellebores have failed to bloom.

Please see our article, Why Hellebores Fail to Bloom (and What to do About it). If these nine reasons do not seem applicable, please contact your local hellebore society for further advice.

I lost 10 Ivory Prince plants to aphids last year, can I replace them in the fall if I find any on sale at our local nurseries?

Hi Lisa –

What a shame. Yes, you can replace them in the fall, provided they are in the ground at least five weeks before the first average frost date, so they are established before winter.

You may want to preventatively apply organic horticultural neem oil in the spring to deter aphids form the new plants.