Infusing your garden with some native wildflowers is a wonderful way to make it more sustainable while creating a unique sense of place. But in order to reap these benefits, both planning and planting right are key!

Growing wildflowers involves a bit more than simply opening up a seed packet and throwing the seeds into the grass, with fingers crossed that in a few months you will find a beautiful mix of flowers bobbing in the breeze.

If you follow that whimsical but sadly unrealistic strategy for getting wildflowers into your yard, you’ll likely be met with disappointment. And so will the bees, birds, and butterflies that visit your outdoor space!

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

To keep you and your neighborhood critters from such chagrin, I’ve compiled my top tips for growing a native wildflower landscape. And I’m going to share those tips with you here.

Here’s a sneak peek:

Tips for Growing Native Wildflowers

Understand the Advantages

Before we get started on the planning part of this gardening project, let’s have a quick review of why using native wildflowers in the landscape is a great idea in the first place, shall we?

Fewer Inputs

First of all, when you choose to grow native wildflowers that are well adapted to your region, you’ll be saving yourself some inputs.

That’s to say, soil amendments, irrigation water, fertilizers – and of course, the time and money needed to apply all of those things.

Since local species are adapted to your natural conditions, you won’t have to change those conditions, apart from providing a bit of extra water to help the wildflowers get established. (I’ll explain more on that point later in the article, so keep reading!)

And by the way, in addition to saving time and money, if you have less water, fertilizer, and pesticides to apply, this happens to be a step in the right direction toward making your landscape more sustainable as well.

Ecosystem Care

Another motivator is that with native wildflowers, you’ll provide better care for your local ecosystem than you can with nonnative flowers.

Nonnative flowers may provide food for adult pollinators, but native flowers provide food for adult pollinators and food for pollinator babies (which is a nice way of saying “larvae”).

Indigenous larvae tend to prefer indigenous plants as food, instead of those from far-flung locales.

That’s because the members of our local ecosystems developed together over long periods of time, and are well-adapted to living together, with one of the most famous examples of this being the relationship between monarchs and milkweed.

If the idea of seeing your wildflowers being eaten up by bugs is making you rethink your commitment to native plant gardening, don’t fret.

As Doug Tallamy explains in his book “Bringing Nature Home,” which is available on Amazon, “as much as 10 percent of the foliage in a garden can be damaged by insects before the average gardener even notices.”

If we won’t even notice 10 percent damage to foliage, then we can probably accept even a bit more than that before we start to feel resentful.

And in a well-balanced ecosystem (which is what we’re aiming for, by using natives), each species also has natural predators to keep it in check.

When you get to watch a monarch caterpillar chomping away at your milkweed, this is a reason to celebrate! You put the food out, and the critter came to it.

That was the whole point, and having your native species chewed on a bit here and there is to be expected. A couple of milkweed leaves in exchange for glimpses of graceful orange fluttering later? Seems like a fair deal to me!

A Sense of Place

But there’s one more, often overlooked reason to plant natives.

When you grow them at home, you can create a landscape that is unique to your location, and shows off the fascinating species that have evolved in that particular area.

Instead of designing a cookie cutter garden that feels like an afterthought, you could have a garden that highlights all the beauty of your local landscape.

If you’re on board with these perks, all that remains is learning how to best approach planning and growing such a landscape.

Before I walk you through the planning process, you might want to grab a notebook, or better yet, your gardening journal, either of which will be very handy for taking notes and sketching out landscape ideas.

And just a heads up – this process may lead to some backtracking as you develop your plan. If you feel the need to loop back and start over as you work the details out, well, just consider it part of the process!

Ready? Let’s begin.

Home in on Your Vision

Before you get started with any of the other steps involved here, you might find it useful to think about what kind of vision you have for your landscape.

Think about what style you are going for. Do you want a fiesta of colors and textures that grabs your attention? A mix of bright colors will help to achieve this festive effect.

Or are you leaning towards a more subdued, soothing landscape that can serve as an unobtrusive backdrop? Choose colors such as pale pink, blue, purple, and white to achieve a sense of calm.

Whatever you do, just because you’re going to be growing wildflowers, that doesn’t mean you need to get too fixated on the word “wild.”

Your landscape does not have to look messy or weedy. Defining the edges of the growing area with bricks or a creative garden path can keep it looking more intentional and contained.

Native species can even be used to create a quite formal design if that’s the look you prefer!

Choose Your Planting Area

Before you start choosing your species, you’ll want to decide where you’re going to install this gorgeous landscape of yours. So have a look at your property and see where it is exactly that you want your wildflowers to grow.

If you’re interested in growing native wildflowers in your yard but are still in the brainstorming stage, here are some ideas that might inspire you:

One option is to go all out and replace your entire lawn with native wildflowers.

Instead of a slate of green grass, your front yard could be full of eye-catching textures and colors. This can be a particularly beneficial option for homeowners who live on a steep slope, where maintaining a lawn can be more challenging.

But tearing up your lawn certainly isn’t a requirement. Do you have a raised bed or a curb strip in need of some TLC? Either of these locations could prove to be wonderful venues to show off some local color.

If you live on a farm, you can create a wildflower strip between pastures. Suburbanites can take inspiration from this concept and plant an unmowed wildflower strip within a lawn.

For those with larger properties, you might consider creating a meadow, which can be an excellent place for growing expansive views of native wildflowers.

Be sure to include a walkway or pathway so you can enjoy it close up too!

When choosing your planting area, be sure to look for opportunities to work with your natural environment. Let me explain.

Do you have a low area that frequently gets inundated with rainwater? Using that area to create a rain garden with well-adapted species can be a good solution for an otherwise difficult spot.

Have a rocky location? Why not create a rock garden?

Some native wildflowers are very well adapted to rocky conditions and would fit right in, creating an attractive landscape feature – and saving you the work of moving the rocks.

Whatever the limitations of your “canvas” are, try to turn them into benefits instead!

But if you aren’t intent on creating a native landscape per se, and just want to add some native flowers to benefit your local pollinators, another option would be to interplant the crops in your veggie garden with native annuals.

Note Your Growing Conditions

Once you have chosen your planting area, it’s time to take an inventory of the growing conditions available to you in that location.

Let’s start with sun. What’s the light like in the area you have chosen? Is it full sun, part shade, or full shade?

If you’re not sure, return to the area several times throughout the day before you decide.

Also, be aware that not all areas will have the same sun exposure throughout the year.

A plot that looks like it’s pretty sunny in the winter may be in full shade during the summer when a nearby deciduous tree has fully leafed out.

Likewise, an area on the north side of your home may look quite sunny during the warm months, but when the sun drops in the sky during the cooler months, this location may be plunged into full shade.

To make sure your wildflowers thrive, choose an area that has adequate sun exposure all year long.

Next, make a note of how much water is available. Do you know how many inches of rainwater a year you receive on average?

A quick internet search should give you the answer – this will serve as a good starting point. You might also consider tracking your precipitation with a rain gauge.

But even in a single backyard, the amount of rainwater that is actually available can vary greatly, depending on things like slopes and soil types.

If water runs off quickly, such as on a slope, conditions will likely be drier than the average yearly rainfall would indicate.

On the other hand, if the planting area is at the bottom of a slope where rainwater accumulates after a storm, that area is going to be wetter than the average conditions on the property.

Once you have determined how much rainfall you have in your planting area and whether it is wetter or drier than average, make a note of these conditions in your journal so you can refer to them when choosing your wildflowers.

And if you’re really not sure whether your soil tends to be wet or dry, try using a soil moisture meter to make this determination. Make sure to read our complete guide to using this handy tool for further info.

Next, you’ll want to examine your soil. If you haven’t already done so, it’s a good idea to have your soil tested.

You may also find it helpful to consult our article on understanding the soil in your backyard, which will give you a look at different soil types, textures, and pH factors.

Once you have some educated ideas about what type of soil you are working with, make sure to note this info down as well.

And don’t forget to note your USDA Hardiness Zone. You’ll need that so that you can choose species whose hardiness range matches your zone.

You might also want to make a note of other influences at play in the planting area. Is your area prone to erosion? Are deer frequent visitors? Is the area next to a busy road? Is it likely to get salty in the winter when roads are de-iced?

Think about any challenges your planting area faces throughout the year and make notes of these factors too, so you can choose species that will hold up well to these conditions.

Once you’ve made a note of your growing conditions and potential challenges, go ahead and take measurements of your planting area so you can accurately calculate the square footage you are working with.

This will help you choose the right number of specimens for your landscape. Make a note of these measurements in your garden journal or notebook as well.

Create Your Wildflower Palette

You’ve chosen your location and assessed the conditions there, so now you’re ready for the exciting part – creating your wildflower palette. That’s right, I’m talking about picking out your plants!

To create your palette, you’ll want to make a list of wildflowers that are native to your region, recommended for your hardiness zone, and which are suited to the growing conditions in your planting area in terms of light, water availability, and soil type.

If you have noted any potential challenges in your planting area, you’ll also want to focus on species that are adapted to those conditions: ones that are deer resistant, good for rocky areas, recommended for erosion control, tolerant of salty conditions, or tolerant of pollution, depending on what you need!

Go ahead and make a wide selection of more species than you need to start with. You can narrow these down later in the design process.

But wait. How do you find wildflowers that are native to your region?

To start with, there are many excellent regional native plant books available, some of which are focused not just on identifying these species, but on using them in the garden as well.

I’ll share a few titles that are on my own bookshelves.

For the Intermountain West region of the US, one of the best selections is “Landscaping on the New Frontier: Waterwise Design for the Intermountain West” by Susan E. Meyer, Roger K. Kjelgren, Darrel G. Morrison, and William A. Varga.

The species recommended in this book are arranged by water needs, a feature I find extremely helpful in my arid climate. It’s available for purchase at Amazon.

Landscaping on the New Frontier

For the Southeast region, my top pick is “Native Plants of the Southeast: A Comprehensive Guide to the Best 460 Species for the Garden” by Dr. Larry Mellichamp, also available from Amazon.

The species in this book are organized by plant type.

Native Plants of the Southeast

And if you’re a resident of the Pacific Northwest, one of my top resources for that area is Eileen M. Starck’s “Real Gardens Grow Natives.”

This is an excellent guide to gardening with native species in the Pacific Northwest, with species organized by light requirements. You can find it at Amazon.

In addition to guide books, the website of your local native plant society would be another excellent resource for identifying local species for gardening projects.

Some of these organizations, such as the California Native Plant Society, have extensive searchable plant databases.

And to add to these resources, I’m going to make a few plant suggestions of my own shortly.

Before we get to those recommendations though, a lighthearted word of warning: While choosing plants can be the most thrilling part of the process, this is also the time to exercise some self-control!

If your planting area is in full sun with dry, sandy soil, then you are going to just completely ignore the species that require deep shade and moist soil that’s rich in organic matter. If you can’t do that, and keep fixating on the shade growers, then you probably need to start over and select a shady location.

And it’s ok to rethink your project! Maybe once you get your shade garden out of your system you can come back later and work on your dry, sunny garden next.

Once you have a broad list of wildflowers to work with, you can narrow your selection during the following portions of the design process.

In addition to the books and websites mentioned, here are a few of my favorite native wildflower recommendations for various regions of the US.

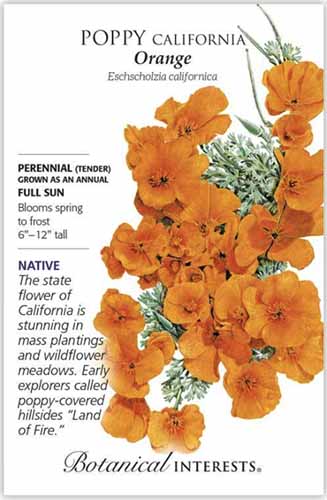

California Poppies

The nodding orange heads of California poppies are a cheery sight to behold.

This species, Eschscholzia californica, is native not just to California, as its name implies, but also to other states in the western US, including Washington, Oregon, Nevada, Arizona, Utah, and New Mexico.

The flowers of this species are bright orange and delicate, fluttering in even the slightest breeze. The plants have silvery green foliage and reach six to 12 inches tall.

This species is lovely when mixed with other wildflowers, but when used en masse to create wide swaths of color, it is truly stunning. Expect these bright blooms to provide a show from spring until your first fall frost.

California poppies are perennial in Zones 8 to 10, but they can be grown in colder zones as annuals, where they will readily self-seed.

Both organic and conventionally grown California poppy seeds are available for purchase in an assortment of package sizes from Botanical Interests.

Find tips on growing California poppies here.

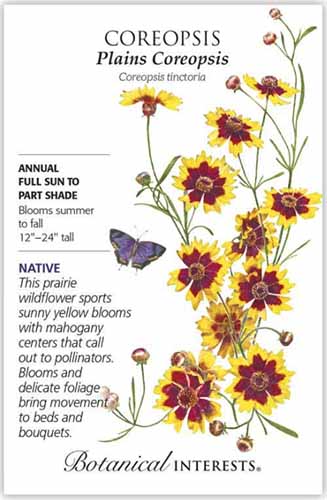

Plains Coreopsis

Native to the central plains of the US, plains coreopsis (Coreopsis tinctoria) makes a bright and cheery addition to any veggie garden, bed, or border.

The flowers are yellow with maroon centers, highly attractive to pollinators, and are held aloft on stems adorned with delicate, wispy foliage that might remind you of cosmos. This species grows to be one to two feet tall.

Plains coreopsis requires full sun to part shade, is adaptable to moist conditions while remaining very drought tolerant, and prefers sandy soil. You can learn more about growing coreopsis in our guide.

This annual can be grown successfully in Zones 2 to 11, and will bloom from midsummer until your first frost.

Plains coreopsis seeds are available in 100-milligram packets from Botanical Interests.

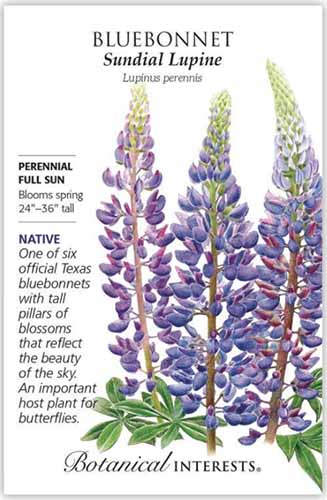

Sundial Lupine

This next selection, sundial lupine, is native to the Midwest and the eastern United States.

Sundial lupine (Lupinus perennis) has palm-shaped leaves and long spikes of purplish-blue flowers, which bloom in the spring. This species grows to be two to three feet tall and 18 inches wide.

Also known as “wild lupine,” this member of the legume family is a nitrogen fixer like its relatives, peas and beans.

Sundial lupine is adaptable to sun or part shade, and to both dry and moist conditions. It is also drought tolerant.

This species grows well in sandy soils but will tolerate other soil types, as long as it has good drainage and a soil pH between 6.8 and 7.2.

Sundial lupine is a host plant for Karner blue butterflies (Plebejus melissa samuelis), a subspecies of Plebejus melissa that is at risk of becoming extinct. In its caterpillar stage, this butterfly feeds only on the leaves of sundial lupine.

Sundial lupine is a perennial that’s hardy in Zones 3 to 8.

Seeds are available in 1.5-gram packs from Botanical Interests.

While some wildflowers have a fairly narrow indigenous range, others have a much larger native distribution, making them good options for a larger group of gardeners.

If you’d like to peruse more options for your landscape, be sure to read our article on 15 of the best native wildflowers for the US and Canada.

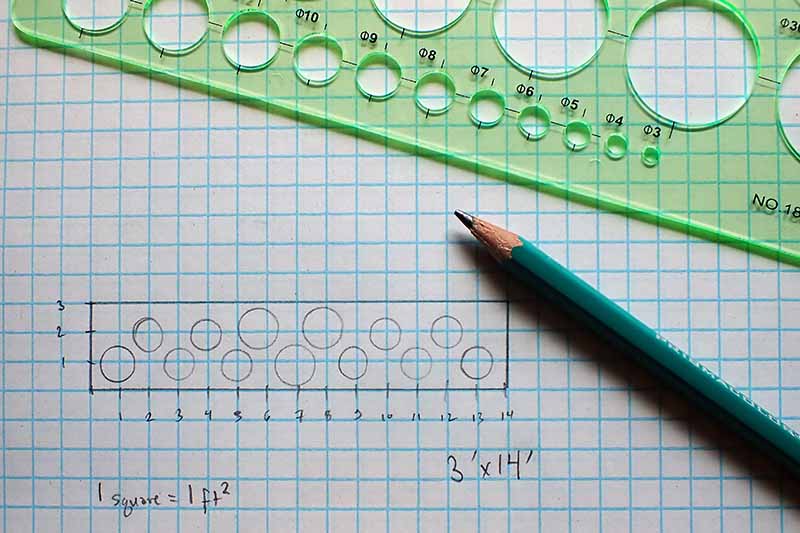

Sketch Your Design

Once you have a selection of species in your plant palette, you can start playing with how to arrange them within your space – something I recommend trying out on paper first!

No worries if you feel you don’t have art skills. A rough sketch drawn from a bird’s eye view will help you fit your selected wildflowers into your garden area nicely, so that they aren’t too crowded or too widely spaced.

But to know how many plants you can fit into your planting area, a drawing made to scale is what you need.

A simple way to make a basic scale drawing is to use graph paper. You can assign each square a specific size, for instance, designating each square in the grid as a square foot.

Remember when you took measurements of your garden area earlier? Now is the time to use those. Draw in the dimensions of your planting area, using the lines of the graph paper as your guide.

Now you can begin to arrange your palette selections on paper. To do this, you’ll need to know the mature width of each plant. Decide how dense you want the landscape to be, and arrange your plants on your grid accordingly.

Sketching out a design is certainly a trial-and-error process, so plan on completing several tries before you come up with your final design.

While sketching your design, there are a few things to consider:

When arranging the wildflowers in your sketch, check the mature height of each plant, and place taller ones towards the back of your landscape, so you will have a clear view of the smaller species in the front.

Another good design consideration is that mass plantings will often give you more bang for your buck. While a single specimen of, say, joe-pye weed, may be just so-so, when grown in a large drift, it becomes spectacular.

Think about the vision you came up with early in the process. What style do you want your landscape to include?

Large irregularly-shaped drifts will create a more natural look.

Want things to look more formal? Lay your wildflowers out in a geometrical or symmetrical pattern.

If your goal is to create a diverse landscape swarming with pollinators, include many different flower colors, but also different types of blooms.

One reason for this is that different types of bees and other pollinators have different tongue lengths, and they will forage from different types of flowers.

Also keep in mind that each wildflower species has its own bloom time. Check to make sure the flowers you are counting on to look good together are actually going to be blooming during the same period.

And to make pollinators happiest, try to have a few different species always in flower throughout the growing season by planning a succession of bloom times.

Finally, remember that wildflowers are only colorful temporarily.

True, some have attractive foliage as well as flowers, but to make your landscape look nice even in the winter months, consider growing your wildflowers amongst native evergreen shrubs or ornamental grasses.

Install and Maintain

Once you have a design, you’ll be ready to get started on installation, beginning with purchasing your live plants or seeds.

If you’re growing from seed, make sure to read each seed packet and follow the directions as to seed depth and sowing time.

Some seeds are best sowed in the fall, so they are cold stratified over the winter. Just like when you pre-seed your veggie garden, you can also pre-seed your wildflower planting.

In the springtime, if you’re trying to get a head start, you can always start your seeds indoors.

Likewise, when working with live plants, make sure you plant them at the appropriate time – usually in the fall or spring rather than midsummer when conditions can be wiltingly hot.

If you are purchasing live plants online, be aware that the most reputable nurseries will ship your order at the appropriate time for planting.

Some native species prefer lean soil, so if that’s the case with your selected species, resist the urge to add amendments. Ideally, you have chosen species that are well-adapted to your natural soil conditions, so those additions won’t be necessary.

Even species that have extremely low water needs will require a bit of supplemental irrigation while the new plants are getting established. This will be particularly important if you are in a dry location or experiencing drought.

Finally, don’t forget that young specimens may not look like what you were imagining when you sketched your design. Depending on the species, it may take some time for the plant to reach its mature size and produce blooms.

While your new wildflowers get established, you can help them out by keeping your plot weeded. Want to make this chore easier? Read our article with tips on how to spend less time weeding.

And don’t forget to mulch! Choose a mulch that is appropriate for your climate, whether you use fallen leaves or some other organic material.

If you’re sowing your wildflowers from seed, wait until the seedlings have germinated and are a few inches tall before mulching.

Once your blooms are spent, you’ll have dead flower heads. In some cases, you might want to deadhead them to prevent self-seeding, and you can save these seeds to plant more flowers elsewhere.

However, removing spent blooms is not always recommended – some dried flower heads and vegetation is quite gorgeous and provides welcome winter interest.

But that’s not the only reason to leave faded vegetation in your landscape.

Many insects use this dead vegetation as shelter for overwintering, such as some solitary bees which may spend the cold months hibernating in hollow stems.

And birds often rely on the dried seed heads of spent flowers for winter food.

Once your perennial wildflowers are established, you may want to occasionally divide spreading specimens – which will give you more material for starting new landscapes!

Ready to Be Best Buds?

Well, fellow flower lover, you’ve done it.

You now have a firm understanding of the advantages of using native wildflowers, you’ve honed your vision for a landscape of your own, chosen a planting area, made notes on your growing conditions, created a plant palette, sketched your design, and learned to plant and maintain your new plants.

Phew! Congratulations! You’ll soon have a new set of wildflower friends – or at least, lots of buds.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this crash course in creating a native wildflower landscape. I’d love to know which species you added to your palette, what type of obstacles you turned into advantages, and how your garden is growing.

Let me know in the comments section below – and yes, sending photos of your own wildflowers is encouraged!

If all this planning has you brimming with excitement for native plants, here are a few more articles to guide and inspire you:

Great article, great advice. How do I prevent some of my natives from growing too tall? I have some that are over 4 & 5 feet. My front lawn looks like a jungle. I’m sure my neighbors are not very pleased.

Hi Anna, I’m so glad you liked the article, thanks for letting us know! It really depends on which plants you’re talking about. Some of them might be able to be pruned – others not. In general, wildflowers grown in garden conditions can sometimes get too leggy because we baby them too much – give them too much water and fertilizer. Cutting back on water and amendments will help some species remain more compact. Another way to keep your yard from looking like a jungle might be to tweak the design just a bit. Sometimes it’s not so much what… Read more »