Jasminum nudiflorum

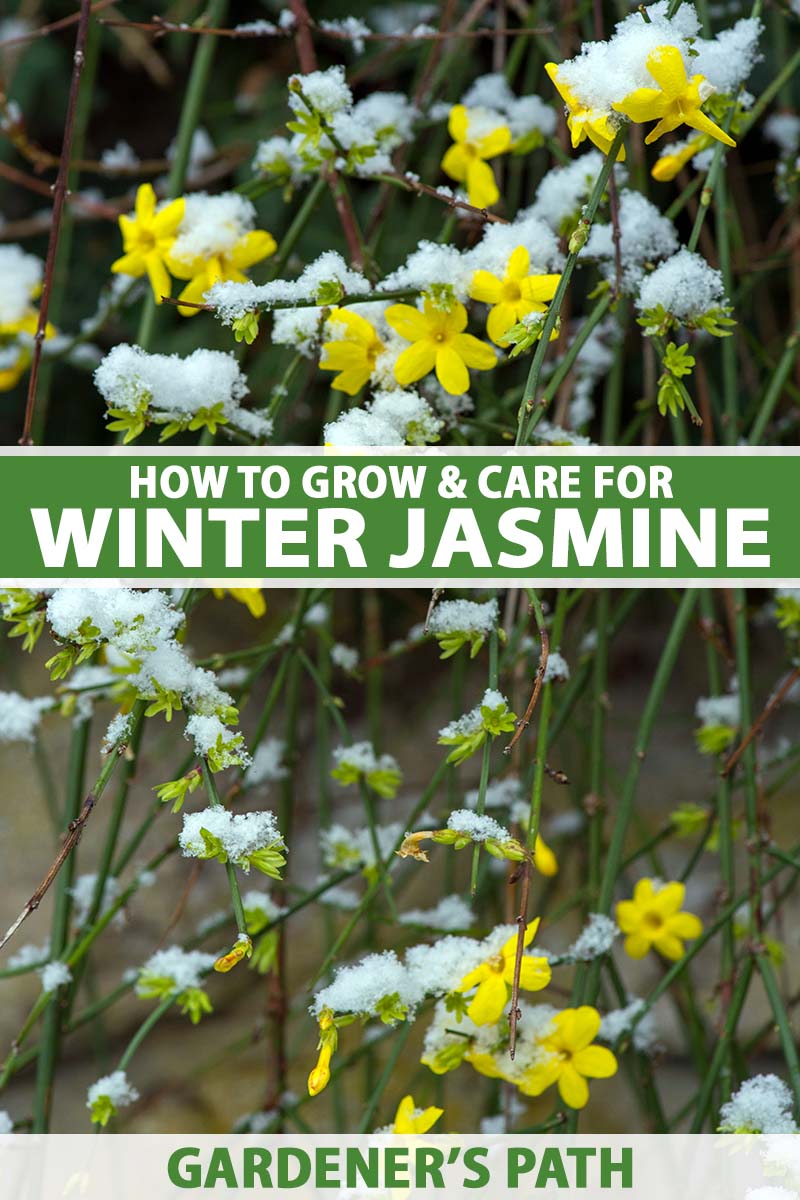

Are you looking for a plant that comes to life when others are withered and dormant, one that offers seasonal color like a camellia, but with less upkeep? Jasminum nudiflorum may be the one for you!

Plants that brighten the sometimes dismal winter months are always popular. Perhaps that’s why winter jasmine has been cultivated for centuries.

Though this species lacks the strong, musky scent that most types of jasmine are known for, it not only adds color to the landscape, it also serves as an important source of forage for pollinators when it blooms in late winter.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

We’ll discuss how to propagate, nurture, and maintain winter jasmine in this article.

Here’s a quick list of everything I’ll cover:

What You’ll Learn

Whether you’re in the market for a low-maintenance plant that can be grown as a cascading vine, a bright ground cover, or a neatly trimmed border planting, this plant checks all of the boxes.

What Is Winter Jasmine?

A member of the Oleaceae or olive family, winter jasmine is related to other blooming plants including lilacs and forsythia. It is one of the over 200 species within the Jasminum genus.

It’s also important to note that winter jasmine should not be confused with pink jasmine, J. polyanthum, which is more fragrant but also blooms in winter. This species is hardy in Zones 8 to 11a, and does not tolerate freezing like J. nudiflorum.

This deciduous shrub is mid-sized, reaching 10 to 15 feet in length at maturity if grown in a vine-like, cascading, weeping shape – like a fountain of bright green canes.

These can be grown with support and trained into a more upright, twining form over time, or they may reach about four feet in height when grown as shrubs with a spread twice as wide.

This plant is a strong candidate for espalier training, and growers may take advantage of its vine-like habit using this method. Branches can be fastened and trimmed to fit along a structure, such as a latticework frame, wire, or string. With frequent pruning, the shape can be maintained for many years.

In mid- to late winter, pinkish-red buds burst open in multiple cycles of small, bright yellow, star-shaped blossoms. These appear individually along the branches, usually before the leaves unfold.

The leaves are glossy and dark green, with an oblong shape. They grow in sets of three in pinnate form, on opposite sides of the branches. While these plants are deciduous, the leaves are susceptible to dying off if they’re exposed to extreme low temperatures below 5°F.

Winter jasmine shrubs look similar to their cousin, the forsythia, but you can tell them apart since forsythias typically grow in an upright shape, like a large, yellow sea urchin, and they reach greater heights if they’re not pruned back. Winter jasmine also tends to look a bit scraggly if it’s not given a trim after it blooms.

In the spring, the bright green, willowy branches can be pruned into a mounded shape that makes a lovely ornamental border. This species is sometimes used as ground cover as well, and it tolerates poor soil and partial shade.

Because this plant needs cool temperatures of 60°F or lower for several weeks to trigger blooming, it’s best suited to USDA Hardiness Zones 6 to 10, where late fall and early winter temperatures don’t regularly dip below 5°F. In cooler temperatures, plants should be protected.

A word of caution is necessary – in some regions where growing conditions are ideal, such as the southern United States, winter jasmine can be somewhat invasive. However, it is not banned because it has a slow, creeping spread and does not tend to choke out native species.

The canes can root if they’re allowed to reach the ground, producing new plants, and it can overtake an area over time without adequate maintenance. The black berries also produce seeds in the summer.

Winter jasmine is excellent for creating a prolific ground cover to prevent erosion or spread over infertile soil, but it can grow out of control if left unchecked. Be sure to keep an eye on this plant to make sure it’s not spreading beyond the area where you intended for it to grow.

Cultivation and History

In 1844, British plant collector Robert Fortune stumbled upon a potted plant in a nursery in Shanghai, China. He was taken with the improbable blooms that brightened the winter bleakness, so he purchased the plant and brought it to Europe.

In the wild in China, winter jasmine grows in thickets along sloping, rocky ravines, which is what makes it such an excellent choice for ground cover and erosion control in the home landscape.

Even though it had been cultivated in China for centuries – where it’s known as “Yingchun,” or the flower that welcomes spring – Fortune is credited with its spread into mainstream popularity among gardeners in the Eastern Hemisphere. In France and parts of the United States, plants have escaped cultivation and naturalized.

Both the genus and species names are Latin, derived from the Persian yasmin or yasamin for jasmine, and nudiflorum, meaning “flowers before leaves” or “naked.”

In the late 19th and early 20th century, winter jasmine was grown free-form along stone walls and fences in the United States and Europe to add color and interest, and planted as a companion with camellias, heliotropes, and lilacs for year-round blossoms.

This plant grows best in full sun or partial shade, and it can not withstand waterlogged soil. However, it does tolerate poor soil that lacks nutrients or that is dense, such as with red clay. To thrive, it needs sandy loam that drains well.

In 1984, winter jasmine won the Royal Horticultural Society’s Award of Garden Merit. Perhaps surprisingly, for a plant with such a long history of cultivation, winter blooming tendencies, and tolerance of neglect, there are only a few cultivars on the market.

Perhaps you could try your hand at producing a new cultivar since there are so few – I’ve always wanted to try! Let’s discuss the best methods for propagating these plants at home next.

Propagation

As I mentioned, propagating winter jasmine is sometimes as easy as allowing the canes to touch the ground, where they often root independently.

If you’d rather manage propagation more closely instead of letting the plant spread at will, you’ll want to keep the canes pruned above ground-level.

Here, we’ll cover propagating winter jasmine from seed, cuttings, and layering, as well as transplanting potted specimens purchased from a nursery.

From Seed

You’ll most likely need to purchase seeds, as cultivated plants only rarely produce berries in the summer.

Soak the seeds overnight in room temperature water to soften them. While they’re soaking, prepare planting cells or individual four-inch pots with loamy soil. You can purchase seed starting mix or make your own using one part coconut coir, one part perlite, and one part sand.

Press the seeds about one eighth of an inch deep in the soil and lightly cover them. Place the tray or pots in a location where they’ll receive eight to 10 hours of direct sunlight per day, and if the temperature isn’t consistently in the 70°F range, consider using a heat mat.

Water or mist the planted seeds until the soil is just damp to the touch, and water or mist as needed to keep the soil slightly moist. You can use a sheet of plastic wrap over the tray or pots, or place them in a clear, lidded plastic storage tote to maintain humidity if you don’t have a greenhouse.

It can take two to four weeks for the seeds to germinate. Once they do, allow them to grow to about four to six inches in height and then you can prepare their permanent planting site. They can be planted outdoors in the ground, or in a container.

Before you move them outdoors, harden them off by placing them outside for a few hours per day in partial shade. Gradually move them into more direct sunlight for longer periods until they’re permanently outdoors.

From Cuttings

Cuttings can be taken in the fall. Choose healthy canes and cut just below a leaf node about six inches from the end.

Strip all of the leaves off of the branches except for a few at the growing end.

Prepare a rooting flat or small pots filled with a mix of one part coconut coir to one part sand. Press it into the flat or pots, and mist until the medium feels damp.

Strip the bark from the bottom half-inch of the canes and dip them in rooting hormone powder.

Stick the cuttings into the soil loosely, spaced about two to three inches apart or one per pot. Place the tray in a clear, lidded plastic storage tote or a greenhouse, if you have access.

If you chose to use individual pots, you can wrap them in a plastic bag instead.

Place the cuttings in an area where they’ll be exposed to indirect sunlight and temperatures at consistent 65 to 75°F. It can take about a month for the cuttings to root, but be sure to mist them regularly to avoid letting them dry out.

Once they show signs of new growth, allow them to become established over the course of two to four weeks before transplanting them as described below. It’s best to move them to larger individual pots and gradually harden them off to the outdoors until you can transplant them to their permanent location.

Layering

As I mentioned, canes of winter jasmine will easily root where they come into contact with the ground. You can use this to your advantage if you’d like to skip some of the waiting involved in sprouting seeds or rooting cuttings.

Choose a healthy cane of an adequate length to be pulled to the ground. Pull it down and mark the location where the cane comes into contact with the soil. This is the part of the branch that you’ll want to prepare.

With a sharp, sanitized garden knife, cut a segment of the bark off of the branch at the point where it will make contact with the ground.

Be sure to leave at least six to 12 inches of length at the growth end. Cut around the perimeter of the top layer of bark, making a circle that goes all the way around the branch.

About one inch further down, cut another circle into the top layer of bark, and then make a slit between the two cuts. Do not cut deeply into the branch.

Remove the cuff of bark you’ve cut away, and scrape off any of the remaining green cambium layer underneath. Dust the exposed inner portion with rooting hormone powder.

Pull the branch to the ground and make sure the cut segment comes into contact with the soil. Place a rock over it, or use wire to hold it in place. Allow two to four weeks for the branch to take root.

Check often to make sure the soil is moist but not wet. Once you observe that a small root system has formed, you can cut the cane free from the parent plant and carefully dig the plant up from the ground to transplant it.

From Transplants

Whether you’ve started seedlings, rooted cuttings, layered canes, or purchased plants, you’ll need to transplant them to their permanent location. It’s best to do this in the spring when daytime temperatures are consistently at least 60°F.

To move them to an in-ground location, choose a sunny site that receives at least eight hours of direct sunlight per day. The soil at the site should be loamy and loose; rake or till the planting area and amend it with compost prior to planting.

Dig a hole about the same depth and twice as wide as the root system of your transplant.

If you purchased a plant from a nursery, be sure to take a close look at the root system and soil in the container to avoid introducing pests or disease pathogens to your garden soil. If the root system doesn’t look healthy, you should address that prior to planting.

Be sure that there are no signs of root damage, such as a slimy texture or blackened roots that are signs of root rot. Check for insect damage as well, such as from grubs or other soil-dwelling insects. Snip off any affected roots and make sure the roots aren’t girdled.

Place the plant in the hole and backfill with soil. Press the soil into place with your hands and water well to settle.

Learn more about propagating jasmine here.

How to Grow Winter Jasmine Shrubs

Winter jasmine spreads readily, rooting wherever it comes into contact with soil. Unless you plan to use it as a ground cover in a large, open space, make sure you place it in a location where it can be pruned easily, or plant it in a container.

Even though winter jasmine is tolerant of neglect and poor soil, these plants will thrive with a little routine maintenance. Loamy soil that is rich in organic matter is best, and compost makes a great choice for adding nutrients that may be lacking.

Plant winter jasmine in full sun to partial shade, but note that in full sun, it may spread more easily. Partial shade can help to keep it in check, slowing growth a bit.

Well-drained soil is a must, as this plant does not tolerate wet feet. Avoid overwatering by providing one inch of water when the soil feels dry on the surface, no more than one to two times per week.

Note that this plant is moderately drought-tolerant once established, and watering should be reduced in the summer, unless you live in a region that experiences very low rainfall through the summer months.

In that case, continue to offer about one inch of water per week.

Be sure to offer support if you’re growing this plant as a twining vine, such as a sturdy trellis or fence. Winter jasmine may need to be tied into place as it grows to train it into position, as it doesn’t climb on its own.

Don’t worry about planting in a location where pets may have access, as this plant is nontoxic and pet safe.

If you plan to grow your winter jasmine in a container, choose a pot or planter that’s about two to three inches wider and deeper than the root system. Use a potting medium of one part coconut coir, one part perlite, and one part sand.

Make sure the container has good drainage; a clay pot is the best choice as it will transpire to allow adequate airflow. Place the pot in a sunny location and provide support to train the plant to climb, or trim it to maintain a mounded shape.

As a ground cover, winter jasmine can quickly fill a large area, so be sure to space plants adequately to avoid dense overcrowding. Leave at least eight feet between plants if you don’t plan to cut them back in the spring.

This shrub makes a good choice for bonsai training as well. See our guide to getting started with bonsai for details.

Growing Tips

- Plant in full sun.

- Ensure that soil is well draining.

- Reduce watering in the summer months, unless your region experiences drought conditions.

Pruning and Maintenance

Prune winter jasmine in the spring after blooming has ended. Blooms are produced on old growth, so pruning will not reduce blooming for the next cycle.

Cut branches back by about a third to rejuvenate it, and shape it so it doesn’t become weedy. New shoots are produced from a central cluster so it can look a little messy if pruning is neglected.

If you’ve planted yours as a ground cover, cut it back to ground level to encourage dense regrowth and prevent invasive, creeping tendencies.

Be sure to cut canes back before they produce berries in the summer, to control unwanted spreading.

Cultivars to Select

There are only a few cultivars available, and they can be a challenge to find.

J. nudiflorum species plants can be purchased in 2.5-quart pots from Home Depot.

Aureum

While ‘Aureum’ produces the same yellow blooms in the winter, and has the same growing habits as the species plant, it has one noticeable difference – the foliage presents in a bright chartreuse color in the spring.

Mystique

Just as with ‘Aureum,’ ‘Mystique’ has the same growth habit and yellow, winter-blooming blossoms, but it also has variegated foliage with silver-white leaf margins that make it a stand-out!

Nanum

While most winter jasmine varieties top out at about 15 feet in length as a vine or four feet in height as a shrub, ‘Nanum’ is a dwarf variety that rarely grows more than three feet tall.

While any of these cultivars can be used, this cultivar in particular makes a fantastic choice for bonsai as it needs less pruning for size.

Managing Pests and Disease

Remember when I said that this plant is super low maintenance? Well, I meant it, and that includes dealing with infestation and disease.

While deer may occasionally browse on the blossoms in winter, they’re not enough of a concern to cause major defoliation. There are only a few other issues to note, so let’s get to it!

Insects

Some insects are almost universally present in the home garden and landscape, and while this plant doesn’t usually suffer major damage from any of them, they can be an annoyance that could also spread to other plants.

Aphids

Do you ever wonder how many aphids there are in the world? It seems like trillions to me, and sometimes, it feels like all of them live in my garden.

As I mentioned, aphids are not usually enough of a nuisance on winter jasmine to cause plants to die, but they can colonize and spread through the garden. They also spread disease with their piercing mouthparts.

Because they’re tiny, they can be very hard to spot, so take a peek at your plant from time to time to make sure you don’t see ants traversing the canes. If they’re present, you may have aphids as well, as the two have a symbiotic relationship.

Check the undersides of leaves for their presence, and watch for other signs, such as yellowing and curling of leaves, or stunting of new shoots.

Insecticidal soap and neem oil are the best options to treat a minor infestation, but there are a number of other ways – we cover them in depth in our guide to dealing with aphid infestations.

Japanese Beetles

Skeletonized leaves are a telltale sign that Japanese beetles are visiting your plants. In spring and summer, you may notice the damage, and if you’re lucky, you can nip it in the bud.

If not, they may go after your roses and other types of flowers, vegetables, or fruit trees next.

The beetles are only about a quarter-inch wide and long, with copper colored wings and metallic green heads. As interesting as they may appear, they’re not native to the United States and can do quite a bit of damage.

They lay eggs in the soil in spring and summer, where they hatch into grubs that grow to about an inch in length.

They’re voracious, devouring plant roots to help them grow until they pupate. The grubs are off-white in color, with four legs at the front of their bodies. They curl into a “C” shape when they’re disturbed.

Because they’re relatively slow, you can gather the adults by hand and drop them into a bucket of soapy water.

If you’d rather not handle them, you can spray plants with neem oil or insecticidal soap to kill them off, but you may need to do so more than once.

Traps can also be an effective means of control if you’ve got a major infestation on your hands.

Spectracide Bag-A-Bug Japanese Beetle Traps

Try Spectracide Bag-A-Bug Japanese Beetle Traps, available at Walmart.

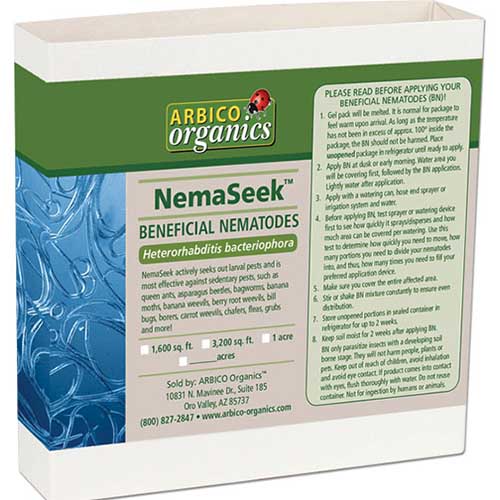

Beneficial nematode species Heterorhabditis bacteriophora can be effective against the eggs and newly hatched larvae.

You can find NemaSeek in quantities from five million to 500 million at Arbico Organics.

Read more about ridding the garden of Japanese beetles here.

Mealybugs

Mealybugs are tiny white insects that colonize on the undersides of leaves, on stems, and in leaf margins. They are related to scale insects, and they feed in the same manner – piercing plants and sucking out fluids.

Because they pierce the surface of the plant, they can easily spread disease, and they tend to breed prolifically once they find a comfortable location with lots of available food.

Learn how to identify and control a mealybug infestation in our guide.

Disease

Just as with pest infestations, winter jasmine typically dodges a lot of the common disease issues. Though rare, here are a few you might come across.

Fusarium Wilt

Fusarium wilt is caused by a type of fungi known as Fusarium solani. These fungi are commonly found in garden soil and affect plants all over the world.

Pathogens can be present in the soil year-round even without host plants, but in warm, wet seasons with temperatures over 75°F, this species will colonize and attack.

Affected plants will show signs of stunting, yellow leaves, and withering, usually starting from the base and working upward, leading to eventual plant death.

Controlling fusarium wilt is difficult, as over-application of fungicides can lead to resistance. It’s best to prune away infected material and discard it in a sealed trash bag, or burn it.

Leaf Blight

Leaf blight is caused by Alternaria jasmini or Cercospora jasminicola fungi. During rainy periods when the ground is wet, pathogens that live in the soil may be splashed onto the leaves and stems of plants.

Once a plant is infected, you’ll notice raised brown spots caused by C. jasminocola, or black or brown spots caused by A. jasmini, developing on the leaves, which later curl and wither.

Young shoots and buds tend to dry up if infected, and there is a significant reduction in blooming.

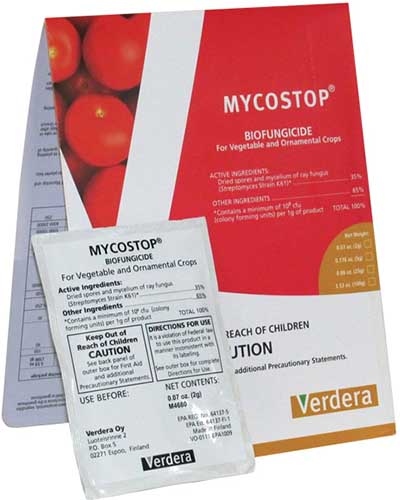

You can treat leaf blight with a fungicide such as Mycostop, but be aware that frequent applications may lead to resistance. This product is available from Arbico Organics in five- and 25-gram packages.

Rust

There are nearly 170 known genera and over 7,000 species of parasitic rust that affect plants all over the world. Most are highly species-specific, attacking only eucalyptus or apples, for example – or in this case, jasmine.

Rust is spread through fungal spores carried by water, wind, or insects. When the spores come into contact with leaves, stems, and fruits, and environmental conditions including moisture, humidity, and warmth are just right, they’ll begin to colonize.

On winter jasmine, you’ll see signs of rust appear as stunting, chlorosis or discoloration of leaves, and the rough brown patches on leaves and stems that characterize this type of fungus. It’s also responsible for some types of gall, cankers, and other deformities, such as blisters on leaves.

While this fungal infection won’t typically kill the plant, it can cause damage to the extent that it needs severe pruning, or it may stunt and deform growth to the point where the only option is to cut it down and remove it.

If your plant is seriously infected, be sure to securely bag up all of the infected material and dispose of it in the trash. Never put infected plant material in your compost or dump pile.

To treat rust, first remove all of the infected plant material that you can see and dispose of it. Dust your plants with sulfur, which will kill any spores that may be present, or spray them with neem oil. You can apply neem oil more than once if necessary, until the outbreak is under control.

Avoid spraying water on the plants, as this may spread the spores. Water at the soil level instead, and try to avoid splashing.

Any time when you prune infected material, be sure to thoroughly sterilize your garden tools before using them again.

Best Uses for Winter Jasmine Plants

This versatile plant may be incorporated into the home garden and landscape in so many ways.

Winter jasmine may be trained to grow on a trellis or structure using the espalier technique. When in bloom, the bright green canes with their striking yellow blossoms make a truly gorgeous presentation.

This species and its cultivars make great candidates for container planting, but be sure to provide protection from extreme cold if you choose to grow it in a pot.

Ground temperatures tend to be two to three times higher in the winter than that of potted soil, so you’ll want to avoid freezing.

When it’s pruned for shape and size, winter jasmine makes a stunning border or low hedge, or it can be grown with support to encourage a taller form.

You can also fill in a large area and keep the plants neatly shaped for added interest in mass plantings, rather than simply planting it as a ground cover and allowing it to spread at random.

For a hedge, space plants about three to five feet apart so they have some room to fill in between.

Using winter jasmine as a ground cover is easy, even on rocky slopes or ground with low fertility. This plant will readily overtake and anchor expanses of soil, rooting in new locations and continuing to creep outward.

Just make sure you prune it back to the ground in the spring to keep its invasive tendencies in check.

When other plants have lost their leaves, this one can act as a perfect privacy screen when planted along a deck or patio where it can cascade like a natural curtain – curtain of blooming gold and green, that is!

If you’re gardening in a region where pollinators remain active for all or part of the winter, this species can serve as an important source of forage.

It can also provide a source of food in early spring, before many other plants have broken dormancy.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Deciduous flowering perennial | Flower/Foliage Color | Yellow/green |

| Native to: | China | Tolerance: | Drought, shade, salt, low nutrients |

| Hardiness (USDA Zone): | 6-10 | Maintenance: | Low |

| Bloom Time: | Late winter-early spring | Soil Type: | Sandy loam |

| Exposure: | Full sun-partial shade | Soil pH: | 5.5-7.0 |

| Growth Rate: | Moderate | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Spacing: | 5-8 feet (shrubs), 8-10 feet (vines) | Companion Planting: | Planting: Basil, camellia, clematis, crocus, hellebore, plumbago, rose, rhododendron, tarragon, winterberry |

| Planting Depth: | 1/8 inch (seed), depth of root ball (transplants) | Attracts: | Bees, butterflies, hummingbirds, wasps |

| Height: | 4 feet (shrub), 15 feet (on trellis) | Uses: | Bonsai, borders, containers, espalier, ground cover, hedge, mass planting, pollinator forage, privacy screen |

| Spread: | 5-7 feet (shrubs), 10-15 feet (vines) | Family: | Oleaceae |

| Water Needs: | Moderate | Genus: | Jasminum |

| Common Pests and Diseases: | Aphids, Japanese beetles, mealybugs; fusarium wilt, leaf blight, rust | Species: | Nudiflorum |

Sunny Color for Your Winter Landscape

Most gardeners don’t mind performing some level of maintenance to keep the plants in their garden or landscape thriving. But it’s nice to come across a plant that is as versatile as this one, and learn that it doesn’t come with a heavy workload.

As long as you’re willing to give your winter jasmine a trim in the springtime to keep it in check, you’ll be good to go! It’ll surely become a plant whose blooms give you something to look forward to every winter.

Do you have a beckoning bare spot in your landscape that this plant would fit into perfectly? Tell us about it in the comments below! If you have any questions, we’re happy to help with those too.

And if you’d like to learn more about growing jasmine in your garden, check out these guides next: