Andromeda, Calluna, Daboecia, Erica spp.

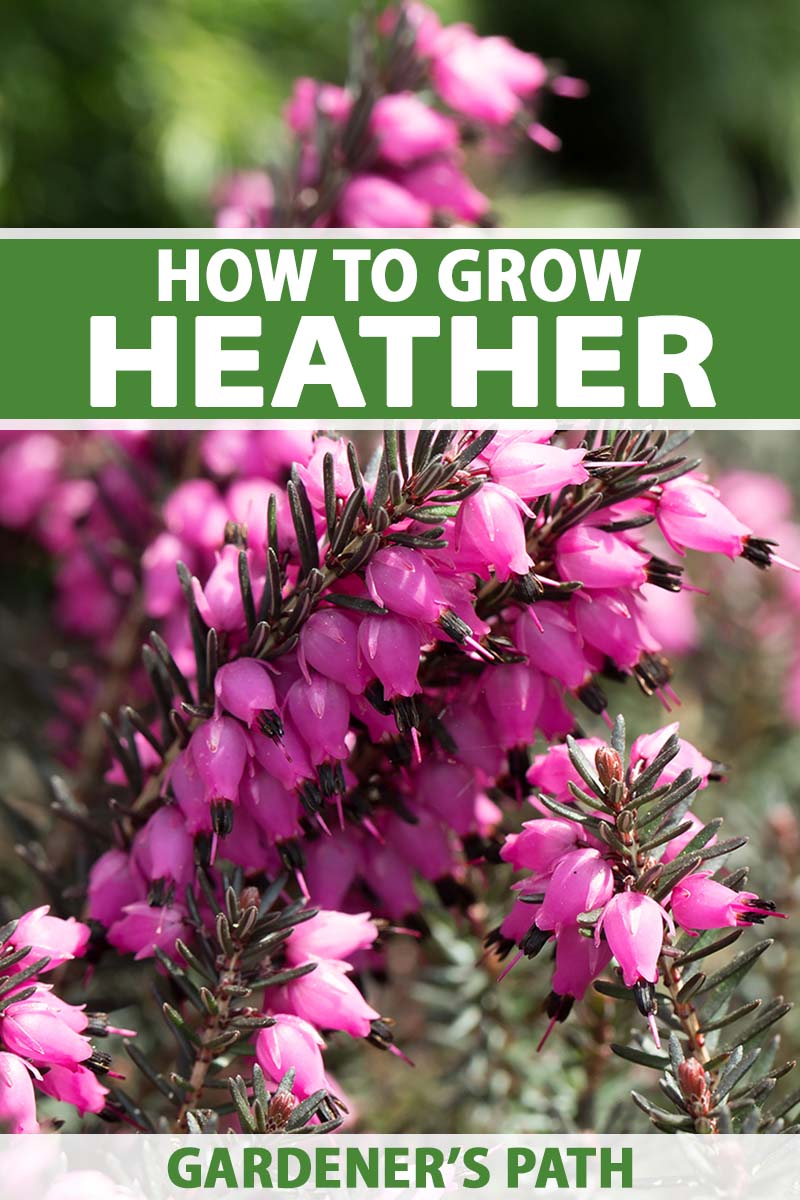

For a tough plant that thwarts hungry deer, marauding rabbits, swarms of aphids, and even most diseases, heather has a delicate beauty all its own.

While it comes from regions that sport some pretty inhospitable environments, heathers have learned to adapt to all kinds of areas.

With flowers that range from white to neon pink, it can add color to the dreariest winter garden, or offer up nearly maintenance-free interest during the hottest summer months.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

I won’t lie, I first fell for heathers because they’re so low-maintenance, but once I discovered the range of colors in both the foliage and the flowers, I was hooked. Maybe you feel the same way?

In this guide, we’ll help you pick the best specimen for your garden, whether you live in the desert or chilly New England, and show you how to make it look its best.

Here’s what you can expect:

What You’ll Learn

Get ready to sit around and just enjoy your heather! No hardcore maintenance required.

What Is Heather?

Heathers all come from the Ericaceae family and belong to either the Calluna, Erica, or Daboecia genus. Andromeda species (bog rosemary) are also included in this grouping.

The so-called “true” heather, or Scotch heather, is C. vulgaris. It’s the only plant in the genus. It’s also called summer heather or ling.

Erica species are called winter heathers, but not all of them bloom in the winter. Daboecia species all bloom in summer.

They are all woody, evergreen perennials that stay fairly short at under 24 inches, and all have tiny scale-like leaves and small but profuse white, purple, red, pink, or mauve flowers.

They’re native to North America, temperate Asia, Africa, the United Kingdom, Ireland, northern Europe, and parts of the Mediterranean.

They generally do well in USDA Hardiness Zones 5 to 8, though some are fine all the way down to Zone 2. And heather can be exceptionally hardy and resilient – to a fault.

In some areas of North America, like North Carolina, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island, Scotch heather is considered invasive.

In other areas like California, Utah, and Nevada, you have to beg it to grow. It has naturalized in parts of Washington, Oregon, Michigan, Maine, Vermont, Massachusetts, New York, and West Virginia.

Don’t confuse these plants with Mexican or false heather, Cuphea hyssopifolia. They look a little similar but this is an entirely different plant from those in the family Lythraceae, which includes pomegranates and crape myrtle.

On the other hand, if you’re wondering what the heck the difference is between heath and heather, the answer is: not much. Heaths are Erica species that have needle-like leaves. Heathers tend to grow a bit taller, but not always.

Don’t get mired in the language. Heathers and heaths are similar and have similar growing requirements.

Some of the most common species and hybrids (and seasons when they flower) include:

- E. carnea (winter)

- E. cinerea (summer)

- E. ciliaris (summer)

- E. x darleyensis (winter)

- E. erigena (winter)

- E. mackaiana (summer)

- E. vagans aka Cornish (summer)

- D. cantabrica aka Irish (summer)

- D. x scotica (summer)

We’ve been breeding heathers for a long time, so you’ll undoubtedly find many other hybrids and a whole bunch of cultivars. Speaking of, let’s discuss the history of this classic plant.

Why don’t we discuss it over a cheeseburger, or some such…?

Cultivation and History

You only have to picture heather’s preferred native environment to understand what will keep it happy in your garden. While rocky soil and salty conditions won’t phase it, it needs acidic, moist soil that is well-draining to really thrive.

It’s also not afraid of cold weather. It can survive long exposure to temperatures down to 4°F.

C. vulgaris grows in Iceland and the Faroe Islands, and it has been found above 8,000 feet on mountains in Switzerland, so that should tell you all you need to know.

Of incredible importance among the people of several different cultures, these plants are far more versatile than many people realize. There are hundreds of native species in South Africa (known as Cape heaths), a dozen in England, and North America has just two.

Heather was used to build huts, roofing, and brooms in Scotland, and the Picts used it to create beer. The plant was also used in Iceland for similar purposes, as well as to make dye.

As with many important plants, people began to cultivate it for both utility and beauty in its respective regions. From there, it began to spread outside of its native range. We don’t have clear records to indicate when this began, but these species have been cultivated and carried around the world for centuries.

The first mention of imported heather in North America dates back to the early 1800s.

Propagation

The easiest option is to head to the nursery and grab a plant or two, but heathers can be propagated in all kinds of different ways.

If you see a plant you love in a neighbor’s yard, ask them if you can take cuttings or do some layering. Otherwise, you can buy or harvest seeds for planting.

From Seed

If you don’t mind whether the plants grow true to the parent or not, you can grow heather from seed. You’ll be spinning the wheel of chance in terms of what the resulting plant will look like, but that can be a good thing.

You might end up with some gorgeous specimen that no one has ever seen before. Or you might end up with a perfectly lovely plant that would fit into a field of wild heathers.

You shouldn’t collect seeds from hybrid plants because these are sterile.

If you want to attempt to create a plant with specific characteristics, you’ll need to hand pollinate the plant by touching a small brush to the inside of the flower on one plant and touching it to the inside of the flower on another plant.

Mark the branch of the pollinated flower and harvest the seeds from that branch to use in your experiments.

At all other times, the plants both need to be covered or isolated indoors in a greenhouse so they won’t be pollinated by insects.

Collect the seeds after the flowers have faded – the seeds will mature a few weeks later. The capsule will feel dry and falls easily from the plant when it’s ready.

Sow the seeds in the early fall spaced an inch apart on the surface of a loamy, slightly acidic seeding medium in a seed tray. Lightly cover with a thin layer of seeding medium.

If you can’t find an ericaceous seeding mix, use a standard mix and work some peat moss in a ratio of about one part peat to four parts soil.

Spray the soil thoroughly with a spray bottle so you don’t disturb the seeds. Place in an area with bright, indirect sunlight.

Keep the soil moist but not soggy at all times. You can place a piece of plastic or glass over the top to help retain moisture, but even still, check several times a day to see if the medium needs to be watered.

You’ll need to be extra patient because the seeds take two or three months to germinate. Once the seedlings emerge, it takes another few weeks for the cotyledons to form and true leaves to emerge.

Once they do and the seedlings are about an inch tall, pinch the tops to encourage branching and bushier growth.

Don’t get too excited, though, you’re not quite there yet.

You still need to wait until spring and after the last projected frost date in your area to transplant the seedlings. Alternately, you can wait until the fall to plant if you want to continue to nurture the seedlings for a bit longer in a controlled environment.

From Cuttings

You can take cuttings and propagate your heather at any time of year. The process takes about six months.

Cuttings can be a little challenging to root, but this method is a surefire way to reproduce a plant that will have the same characteristics as the parent.

Timing and stem selection depends on the species. C. vulgaris and Daboecia cuttings are best taken in the middle of summer after flowering is complete.

Erica cuttings are best taken in the summer as stems are starting to bud. But don’t use flowering branches – choose those that aren’t blooming yet.

To remove a cutting, gently and slowly pull a stem down to peel it off the main stem. The goal is to ensure that you remove a little bit of “heel” along with the stem.

Place the cutting into a four-inch pot (not a compostable one) filled with half sand and half well-rotted compost. Firm around the cutting and soak the medium well with water.

Place a plastic bag over the pot. You can tent the plastic away from the cutting by placing a chopstick or pencil in the pot. Place in a spot with bright, indirect light with temperatures that don’t fluctuate too dramatically.

Check daily to make sure that the soil is moist but not soaking wet. The plastic should also have some condensation on the inside. If not, add water.

Keep an eye on the soil and the cutting for any sign of mold or mildew. If you see any, spray the cutting with copper fungicide every two weeks until the fungus is no longer present.

Don’t have copper fungicide in your gardening toolkit already? Grab Monterey’s Ready-To-Use liquid copper fungicide at Arbico Organics in a 32-ounce spray bottle.

Monterey Liquid Copper Fungicide

After about four or five months, you’ll likely start to see new growth, or if you give the cutting a little tug, it will resist. That means roots are forming. If after six months neither of these things are happening, the cutting failed to root and you should toss it.

Once your cuttings have several new leaves (and assuming the weather is right, with no sight of frost for at least a month), plant out in the garden as you would a transplant.

Before you set it in the ground, harden it off for about a week. This involves placing the cutting outside in a protected area for about an hour and then bringing it back in.

The next day, add an hour before bringing it back on. Continue adding an hour each day until the cutting is able to stay outside for a full eight hours.

From Seedlings or Transplanting

Heathers have long, deep roots, so you need to be careful as you remove them from their container and transplant them into their new home. You also need to dig a sufficiently deep hole.

However tall the longest stem is, dig a hole at least three times as deep and twice as wide. Remove the plant from its container and hold it over the hole so the crown sits at the same height it was in the container.

Fill the hole back in with loosened soil and place the seedling or transplant in the hole. While you are still holding the plant, fill in around it with soil. Water well and add additional soil if needed.

Layering

Layering is my favorite method of propagating heathers because it’s so incredibly simple and requires little effort.

Gently pull down an outer branch or multiple branches on different sides of the plant. Dig a trench where the branch will lay and press the branch into the trench.

Cover with soil and peg it in place using rocks or bent wire. Make sure the tip is out of the soil and pointed up.

Keep the plant watered as you normally would and just let nature take its course. After at least nine months, but probably more, roots will have formed on the buried section.

Remove the anchor and give the cutting a little tug. Does it feel firm? Is there new growth popping up out of the soil? Time to dig it up.

Clip the branch away from the main plant and dig it up, taking care to remove the full root structure by digging at least six inches deep and three inches on either side of the cutting.

Read more about heather propagation here.

How to Grow

If you live in an area that is fairly cool and wet, such as the Pacific Northwest, you are in ideal heather-growing territory.

If you want to grow true scotch heather (Calluna vulgaris), with few exceptions, you need to live somewhere with a similar environment to its native region of Scotland and England.

The soil pH should be below 6.5 and stay reasonably moist but still be well-draining, though some species can handle neutral or even alkaline soil.

For most species and cultivars, full sun is best, though a little shade in the heat of the afternoon in places that experience sweltering summers is a welcome thing. Less than six hours of sun per day, and your plants will be leggy and they won’t bloom well.

If you don’t naturally have acidic soil, you can build a raised bed or grow in containers.

Don’t try to alter the pH of your soil – it ends up being a constant battle and the plants will never be as happy as they would otherwise.

Instead, pick E. carnea, E. erigena, E. x darleyensis, E. x griffithsii, D. cantabrica, or D. x scotica. These are all fine in neutral to alkaline soil with a pH of up to 8.0.

Most species like consistently moist soil, though the top half-inch of soil can dry out without seriously harming the plant.

Once established, they can tolerate occasional drought. If you live somewhere that tends to be dry, choose one of the species listed in the section below.

Heathers for Warm Regions

You probably know that heathers love cooler weather. Anyone who has read a novel based in Scotland has heard about the heather blooming across the rolling hills of the moorlands.

What you don’t hear about are the luscious fields of heather flowering in the harsh California sun.

But news flash! You can grow heather in warm regions. I had a lovely patch in my Utah garden and I’ve seen lots of people succeed in California and Nevada. You need to pick the right spot and you should choose a species that doesn’t mind a little heat.

Tree heathers (E. erigena or E. mediterranea) and Erica x darleyensis and its cultivars such as ‘Darley Dale,’ ‘Furzey,’ ‘George Rendall,’ ‘Silberschmelze,’ and ‘Arthur Johnson’ do well even in the long, dry summers of western regions.

E. herbacea ‘Springwood White,’ C. vulgaris ‘Sister Anne,’ and ‘Californian Midge,’ as well as E. vagans ‘Mrs D.F. Maxwell’ are also happy in warmer, drier weather.

Give them full sun and be sure to keep the soil moist. They may also benefit from some afternoon shade.

Fertilizing

Imagine heather growing on a rocky, windy hillside near the ocean and you can probably see why this plant isn’t demanding when it comes to fertilizer. You probably won’t ever need to fuss with fertilizer, particularly if you offer mulch.

Potted heathers will need feeding. Use one formulated for ericaceous plants.

Down to Earth makes an acid-loving plant mixture that will work perfectly. Pick up a one-, five-, or 15-pound supply at Arbico Organics. Apply once in the spring for summer-blooming types or in fall for winter types.

Alternately, fertilize with well-rotted compost mixed with equal parts peat moss. Normally, I discourage people from using peat since it is a limited resource, but with heather, the two go together like peanut butter and jelly.

Peat is acidic and it helps to keep the soil nice and sour, just like heather wants it to be.

Growing Tips

- Plant in full sun in most areas.

- Keep the soil moist until established.

- Fertilize potted plants once a year.

Pruning and Maintenance

Add mulch every year in the spring for summer types and in the fall for winter types. Mulch with leaf mold, peat moss, or shredded wood such as pine.

Tree heathers should be lightly trimmed, removing about a quarter of the length off of all of the stems, in the fall for the first two or three years. After that, don’t prune them back at all except to remove dead or diseased wood and spent blossoms.

Trim C. vulgaris and Daboecia flower heads off in February or March before new growth and blooming starts. At the same time, cut the stems back by about a third.

Otherwise, they tend to become leggy and woody, and blossoming is reduced. Don’t prune into bare wood, because the stem won’t develop any growth beyond that point and you’ll be left with an ugly bare stem.

Winter-blooming Erica species need the same treatment later in the year, usually around March or April, when they’re done blooming and seeding.

Don’t wait too late in the year because you’ll be cutting into the tissue that will produce next year’s blossoms. Summer-blooming types should be pruned in the same way in the fall after flowering.

E. x watsonii, E. x williamsii, E. x darleyensis, and E. x oldenburgensis can all be pruned back by half or more because they blossom on new wood and do best when severely pruned back to maintain a good shape.

If the leaves begin to turn yellow, test the pH of your soil. Alkaline soil will make the foliage turn yellow.

In regions that experience fluctuations between warm days and extreme cold during some years, like New England and parts of the northern midwest, the wood may become damaged and split. If this happens, trim the plant back to the ground to encourage new growth to emerge.

Species and Cultivars to Select

There are some beautiful heathers out there, and new cultivars and hybrids are popping up all the time.

You’ll usually find the ones that are best suited to your area by heading to a local nursery.

Big chains and home stores tend to carry the types that do well in most regions, but if you want to find those that will really thrive in your particular environment, it’s worth seeking them out from local stores or online.

Also, a quick note on those shockingly vibrant heathers you might see in some nurseries or garden centers: These so-called “painted” heathers are covered in dye and they will eventually grow out into their natural color. If you like the bright color, plan on it only sticking around for a year or two at most.

Below are a few cultivars that we love. They all have stand-out color and are known to be particularly hardy and showy. As the iconic Heather Chandler once said, “I shop, therefore I am,” so let’s start shopping.

Albert’s Gold

E. arborea var. alpina ‘Albert’s Gold’ is a tree heather with golden-green foliage that practically glows in the garden.

Of course, the white flowers are beautiful, but the foliage is so pretty that it alone is enough to recommend it. This variety flowers from February to March in most areas.

Dark Beauty

Royal Horticultural Society’s (RHS) Award of Garden Merit winner C. vulgaris ‘Dark Beauty’ is a standout because of its bold, ruby-red blossoms that emerge in July and stick around through October.

A sport from another exceptional cultivar called ‘Darkness,’ it has deep green foliage and stays extremely compact.

Darley Dale

Erica x darleyensis ‘Darley Dale’ is one of those heathers that doesn’t flinch if you keep it in a sunny, dry, warm area.

It’s also covered in pink and purple flowers from December through April, which means color galore all winter long.

Firefly

‘Firefly’ is a Calluna cultivar that offers year-round color, which is part of the reason that it nabbed the Award Garden of Merit from the RHS.

The red-brown foliage stands out in a garden of green during the spring and summer before turning bright brick red in the fall and winter. Meanwhile, from August to October, tall spikes of purple flowers crown the plant.

Kerstin

The lovely ‘Kerstin,’ a C. vulgaris cultivar, is all dressed up in bright mauve flowers during the summer. The foliage is gray and the new shoots, which emerge in the winter, are pale yellow.

As a result, you can enjoy year-round color when you welcome her to your garden. This is another RHS Award of Garden Merit winner.

Silver Queen

C. vulgaris ‘Silver Queen’ is an RHS Award of Garden Merit winner too, and it’s easy to see why.

The silvery foliage is topped by lavender-mauve flowers during the summer, and the foliage won’t fade or turn green during the winter as it does with some cultivars.

It has a compact growth habit that is as wide as it is tall, which makes it versatile in the garden. Because of all these combined characteristics, it has earned a reputation as one of the best silver foliage types.

Springwood White

E. carnea ‘Springwood White’ is another cultivar that can handle dry, warmer areas without suffering. It has a trailing growth habit and scads of silvery-white, urn-shaped flowers that bloom nonstop from December through May.

Perfect for hanging baskets or winter container color, this is yet another RHS award winner in the Garden of Merit category from 1930, and it has remained a reliable and beloved plant ever since.

There is also a ‘Springwood Pink’ version that was cultivated from a seedling of this plant. It’s similar in all ways except it sports bright pink flowers.

Vivellii

If you prefer an Erica species and want year-round color interest, E. carnea ‘Vivellii’ is a smart choice.

Not only does it bloom from January through March with bright pink and purple blossoms, but the foliage turns a deep bronze at the same time. For the rest of the year, the leaves are medium green.

Wickwar Flame

RHS Award of Garden of Merit winner ‘Wickwar Flame’ is an extraordinary Calluna cultivar that gives you vibrant four-season color.

The foliage is golden yellow and red during the summer before transitioning to bright copper-red in the fall and winter. While the mauve summer flowers are lovely, they’re really secondary to the striking foliage.

Managing Pests and Disease

If you plant your heather in the right spot and provide it with a minimum amount of maintenance, chances are pretty good that you won’t ever have to deal with pests or diseases.

That said, no plant is immune to problems. So, what’s your damage, Heathers? Let’s figure it out.

Insects

I don’t know about you, but when I come across a type of plant that isn’t pestered by aphids, I want to fill my entire yard with them. Can you relate? If so, heather is about to become your new best friend.

However, that doesn’t mean you’re totally out of the woods when it comes to pest problems. Here are a few you might bump up against:

Scale

Oystershell scale (Lepidosaphes ulmi) is an armored scale insect that feeds on hardwood plants. If you hunker down and look at them very closely, their shells resemble an oyster shell, hence the name.

The eggs hatch in late spring and that’s when you start seeing their numbers really increase. Once that happens, they can quickly suck the life out of your plant, one stem at a time.

Insecticides don’t really work, since these pests have a protective outer shell, but they’re easy to remove.

Just head outside with a plate and a rubber scraper and scoop the insects off the wood. Keep at this for a few days and you should have things under control in no time.

Learn more about how to manage scale in our guide.

Spider Mites

Spider mites are tiny little arachnids in the Tetranychidae family. In small numbers, they don’t pose much of a problem, but when the numbers build up, they can cause the shoots and branches to die off.

Look for fine webbing all over the plants rather than looking for the insects themselves. They’re tiny.

To learn how to treat them, read our comprehensive guide.

Disease

In general, you don’t have to stress about diseases taking out your lovely heathers. There are two that you really need to keep an eye out for, and both can be treated fairly easily if you catch them early.

Powdery Mildew

If you garden for long enough, you will encounter powdery mildew. It’s extremely common, especially in warm, dry climates with high humidity.

Rather than looking for the powdery white coating that is evident on many other species, this disease shows up in heather on the young leaf tips.

Initially, the tips emerge red before transitioning to yellow and then brown. After that, they die and fall off the plant.

Despite looking different, you should treat it as you would powdery mildew on any other plant. Our guide has lots more information.

Root Rot

There are three types of pathogens that can cause the roots of your plant to rot.

The first is caused by the fungus Armillaria mellea and the second is caused by oomycete species in the Pythium genus. The third is Phytophthora cinnamomi, another water mold, or oomycete.

The symptoms are the same, causing wilting and stunted growth. Underground, the stems turn black and mushy. Once they die off, the top part of the plant will collapse. Armillaria isn’t common, while Pythium is.

Being careful about how you irrigate can go a long way to preventing this disease since it is spread by water. Don’t overwater your plants and water at the soil level rather than on the foliage.

Once this disease infects your plant, your best chance at saving it is to treat the soil with a fungicide that contains the beneficial bacterial Streptomyces strain K61.

Mix with water according to the manufacturer’s directions and soak the soil. You will need to reapply the fungicide multiple times before you can be sure the disease is gone.

Arbico Organics carries five- or 25-gram packets of Mycostop, which contains this wonder bacterium.

E. persoluta is resistant to root rot, if you’d rather just not worry about this problem in the first place.

Best Uses

Heathers excel in rock gardens, as container plants, or in rugged spots that don’t have the loamy soil that most species seem to love. They’re an excellent option in areas where deer or rabbits are a problem.

Grow winter-bloomers with other plants that offer cold-season color like hellebores. Rhododendrons, azaleas, and other spring- or summer-blooming plants in the Ericaceae family all go well with summer bloomers.

While a single heather can be lovely, a grouping of three or five can make a statement. Most of the time, heathers look best when allowed to grow informally with a natural shape. They don’t do well if you’re trying to give them a formal shape.

Don’t plant under trees or in areas that are extremely dry or particularly soggy.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Perennial woody evergreen | Flower / Foliage Color: | Pink, orange, white, purple/red, bronze, orange, green |

| Native to: | Asia, Africa, North America, Europe | Tolerance: | Drought, hard freezes |

| Hardiness (USDA Zone): | 5-8 | Soil Type: | Rocky, sandy, loamy |

| Bloom Time: | Spring, summer, fall, winter (depends on variety) | Soil pH: | 5.5-8.0 |

| Exposure: | Full sun to partial shade | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Spacing: | 1 inch (seeds); 12 inches, depending on variety (transplants) | Attracts: | Bees, butterflies |

| Planting Depth: | As deep as in original container, lightly cover seeds | Companion Planting: | Azalea, hellebore, rhododendron |

| Height: | Up to 3 feet | Uses: | Rock gardens, container planting, specimen |

| Spread: | Up to 3 feet | Order: | Ericales |

| Water Needs: | Moderate | Family: | Ericaceae |

| Maintenance | Low | Genus: | Andromeda, Calluna, Daboecia, Erica |

| Common Pests and Diseases: | Scale, spider mites; powdery mildew, root rot | Species: | Carnea, cinerea, ciliaris, darleyensis, erigena, mackaiana, vagans, cantabrica, scotica |

Foster Healthy Heathers No Matter Where You Live

There are heathers for a lot more areas than many people realize, so don’t feel like just because you are raising plants in sunny California or frigid Maine that you have to forgo the pleasure of their company.

They’re much more adaptable than we give them credit for.

Beyond that, they’re so deer, pest, and disease-resistant that you don’t have to worry about coddling them just to keep them alive.

What kind of heath or heather are you growing? Let us know in the comments section below!

Love heathers for their ability to bring you color during the dreary winter months? Here are a few other flowering plants that might pique your interest: