Symphoricarpos albus

Looking for something different for your yard? How about your very own Snow White in the form of a shrub?

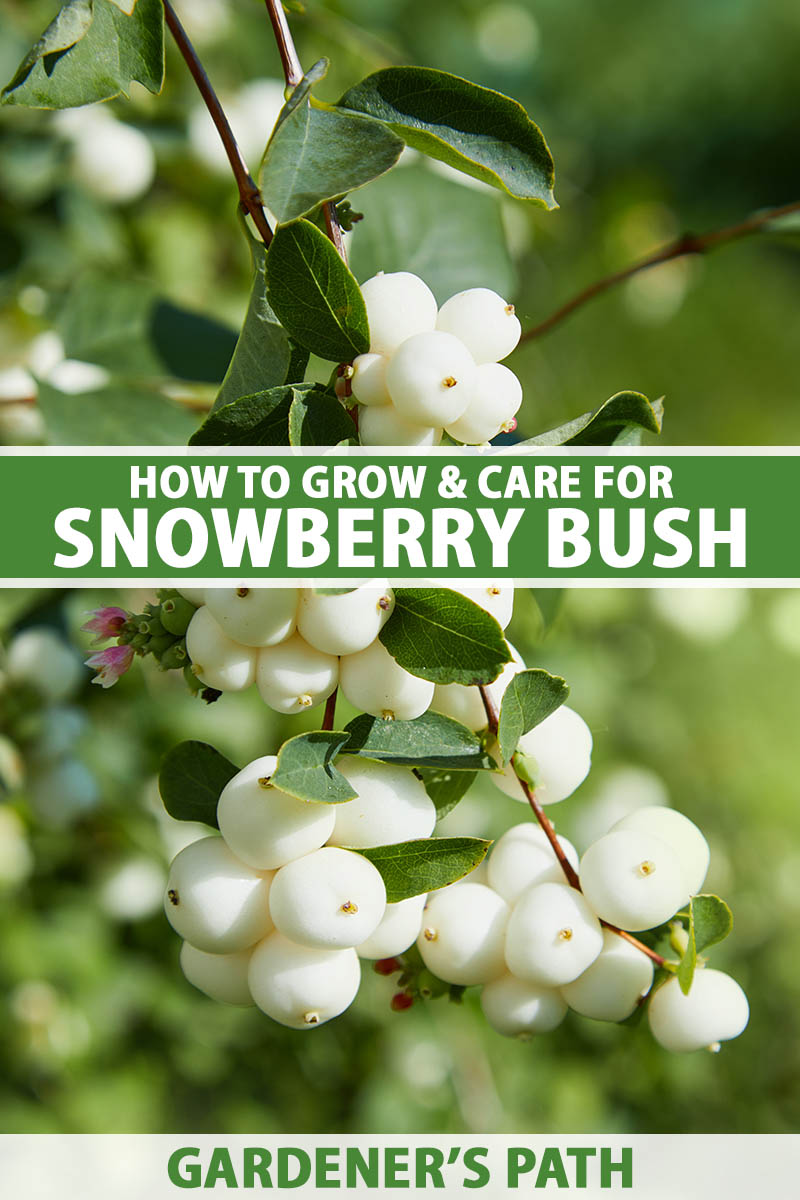

The bright, snow-white berries of snowberry bush will provide both a vision of beauty for the eyes, and a feast for your neighborhood birds!

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

Whatever your reason for growing this adaptable shrub, this article will guide you through the entire process – from propagation to planting to long term maintenance.

We’ll also provide tips on where to purchase snowberry bush specimens of your own, as well as any supplies you might need.

And we’ll offer you some ideas touching on the many different purposes this shrub can serve for landscaping.

Ready to get started? Here’s what we’ll cover:

What You’ll Learn

What Is Snowberry Bush?

Snowberry bush (Symphoricarpos albus) is a multi-stemmed, deciduous, woody shrub named for its striking white berries.

Plants have a bushy, rounded growth habit with dense, arching branches. These shrubs grow to be two to six feet tall and wide, attaining larger dimensions when more water is available.

The foliage of S. albus is bluish green, with leaves held opposite each other on their stems.

Snowberry bush leaves display a lot of variation – they range in size from one to four inches long, are elliptical, oval-shaped, or irregularly lobed, and the leaf margins can be smooth or finely serrated.

The stems of the snowberry bush are light to dark gray, with older bark taking on a purplish appearance.

The plant’s small, bell-shaped flowers are pinkish white, dainty, and fairly inconspicuous, appearing in clusters along stems in late spring or summer.

The berries that give snowberry bush its name are showy and appear in autumn, around the same time that its leaves fall.

These berries often remain on their branches throughout the winter, and are attractive to birds – as well as to gardeners!

These shrubs also produce suckers, which can allow them to form dense thickets.

Cultivation and History

Snowberry bush has a very wide native range throughout North America, occurring primarily in temperate deciduous forests and spreading from Northern Canada and Alaska, throughout the northern US and down to Baja California, Mexico.

In the eastern part of the US, the southernmost end of the plant’s range is North Carolina, while in the western half of the US, it grows as a native shrub in every state except Nevada, Arizona, and Texas.

This species is a member of the honeysuckle family or Caprifoliaceae, a plant family which also includes pincushion flower, valerian, corn salad (also known as mache greens) – as well as Japanese honeysuckle, the vines you might have enjoyed sipping nectar from as a kid!

Did you know there are many different types of honeysuckle to grow in your garden? Learn about 13 different types of honeysuckle in our article!

Classified in the Symphoricarpos genus as S. albus, snowberry bush is also known botanically as S. racemosus and S. rivularis.

In more common terms, it’s also known as “common snowberry,” “upright snowberry,” “white snowberry,” “waxberry,” and “white coralberry.”

These days, this plant is considered toxic, however various parts of the shrub have been used as a medicinal plant by different Native American peoples, such as the Ojibwe, Cree, and Nez Perce.

In addition to its medicinal uses, the berries contain lather-producing saponins, and snowberries have been used as a shampoo and soap.

For landscaping and gardening uses, common snowberry has a moderate to fast growth rate, is a low-maintenance plant, and can be grown in USDA Hardiness Zones 2 through 7.

Snowberry Bush Propagation

Common snowberry can be propagated from seed, cuttings, suckering, or layering – and we’re going to discuss all four methods here, as well as how to transplant specimens.

Let’s start with seed propagation!

Direct Sowing Seed Outdoors

Propagating common snowberry from seed requires that gardeners have a hefty dose of patience because of the seeds’ lengthy stratification requirements.

S. albus seeds germinate best with a warm, moist stratification period of 45 to 90 days, followed by a cold, moist stratification period of five to six months.

If you are direct sowing outdoors, the stratification periods can take place outdoors and are part of the sowing process.

That means seeds need to be sown in summer and kept moist – despite the likelihood that you won’t see any activity from those seeds for several months!

To sow seeds outdoors in your garden or yard, first clear the planting area of any weeds.

The soil does not need to be amended, but working a handful of well-rotted compost into the soil will improve most soil conditions, and will assist with water retention.

Keep in mind that the final spacing of these plants should be two to six feet apart and plan accordingly.

Next, firm up the planting area by patting it gently with your hand.

Now sow seeds one-quarter to half an inch deep, then pat the soil over the sown seed to ensure good contact between seed and soil. Water in gently, and keep the seed bed moist.

Once germination occurs, water seedlings to keep the soil moist in absence of rain until seedlings are well established – that’s to say, until they are several inches tall.

Sowing Seed Indoors

Gardener, your goal will be to have seeds germinate in spring, so start this process during the summer to allow enough time for the two long periods of stratification.

To replicate the natural stratification process indoors, place seeds in a resealable plastic bag filled with moist vermiculite and store at room temperature in a dark location for 45 to 90 days. This is the warm, moist stratification period.

After that period ends, move the bag to the refrigerator for 180 days for a phase of cold, moist stratification.

I highly recommend using a garden planner or online calendar to keep track of these long wait periods! And don’t forget to keep the medium moist during this long wait.

In springtime, once you are ready to plant the snowberry bush seeds, sow them one-quarter to half an inch deep and keep the soil moist until seedlings germinate.

After germination has occurred, water plants in the absence of rain to keep the soil moist. Once plants are established, watering can be reduced.

From Cuttings

Looking for a late winter gardening project? That’s the best time to propagate S. albus from cuttings.

To propagate new plants from cuttings, use a pair of sterilized garden pruners to prune off five- to six-inch-long sections of hardwood stem that are at least pencil-sized in thickness.

Use the pruners to remove any branches, buds, or leaves from the bottom two to three inches of each cutting, as well as any remaining fruit.

And if you’re working with more than one cutting, keep the other ones moist by wrapping them in a wet paper towel while you prepare each cutting.

Pick up a cutting and trim the base of the stem at an angle, then dip the angled end in a rooting hormone, such as Olivia’s Cloning Gel.

A great product to keep on hand for various gardening and propagation projects, you’ll find Olivia’s Cloning Gel in two-, four-, or eight-ounce bottles from Arbico Organics.

After dipping the cuttings in rooting hormone, stick each of them into its own four-inch pot filled with a sterile, 50:50 mix of sand and vermiculite or perlite.

Use a spray bottle to moisten the growing medium and cuttings, then place them in a greenhouse – or cover each cutting and pot with a transparent plastic bag to serve as a mini-greenhouse.

For the first four to six weeks, keep the pots warm at 75 to 85°F, using a heat mat if necessary, such as the Hydrofarm Jump Start Heat Mat.

The Jump Start Heat Mat is available for purchase in several different sizes from the Hydrofarm Store via Amazon.

I like to place my propagation projects on a tray, then place the heat mat under the tray to keep it dry.

Mist these cuttings regularly to keep them and their growing medium moist, and expose them to long days of bright light, such as you would find in a greenhouse.

If you’re undertaking this project in your home rather than a greenhouse, you may need the assistance of a grow light.

You can learn more about using grow lights in our article.

The cuttings should be well rooted within four months. At this point, begin to water them normally.

The rooted cuttings can now be transplanted into gallon-sized nursery pots filled with potting soil, such as Tank’s Pro Potting Mix.

Tank’s Pro Potting Mix 1.5 Cubic Foot Bag

You can purchase a 1.5-cubic-foot bag of Tank’s Pro Potting Mix from Tank’s Green Stuff via Arbico Organics.

Continue growing the plants in greenhouse-like conditions for two more months, then begin to harden them off prior to transplanting.

Just like with annuals started from seed indoors, shrubs and perennials started indoors or in greenhouse conditions need to be hardened off before planting them outdoors.

From Suckers

Snowberry bushes can send up suckers – new stems that emerge from the plant’s rhizomes. Thrifty gardeners can take advantage of this phenomenon to propagate additional plants.

Once suckers are observed, wait until the plant is dormant during the winter months. Dig up the sucker, severing it from the mother plant, and transplant the young shrub into the desired location in your yard or garden.

Not sure if you’ll be able to identify the sucker once its leaves have fallen?

Here’s a tip: tie a brightly colored twisty tie on the sucker while it’s leafed out, so you’ll be able to recognize it again once its leaves have fallen.

From Layering

New specimens of snowberry bush can also be propagated via layering, a project for early spring.

To achieve this, select one of the lower stems and bend it gently to make contact with the ground if it isn’t already touching.

Without severing it from the plant, cover the part of the stem that touches the ground with a few inches of soil, making sure the growing tip at the end of the stem is not covered.

Affix the buried stem to the ground, weighing it down with a brick or rock.

Keep the soil moist where the stem is buried and allow the layered stem to root over the next year.

The following spring, sever the stem from the parent plant with a pair of sterilized garden pruners, but allow the new plant to recover for a few weeks before moving it.

After two or three weeks have elapsed, the new shrub can be transplanted to a different location in your garden or yard.

From Transplants

Whether you grew a snowberry bush yourself or purchased one from a nursery, you’ll eventually want to transplant it into the soil.

No? Want to keep growing your snowberry in a container? Be sure to read our article on growing shrubs in containers first!

Autumn tends to be the best time to transplant shrubs for most gardeners.

However, there are some exceptions, such as for those of us who live in very arid locations that are also very cold in the winter.

In this case, spring may be a better option for transplanting shrubs since it can be hard to keep new additions properly watered during cold, arid winters.

In addition to choosing the appropriate season to do your transplanting, plan this project for an overcast day, or do it after the day has cooled. Plants will suffer less from transplant shock when they don’t have the full brunt of the sun shining on them.

Once you are ready to get planting, dig a hole twice as wide as the plant’s nursery pot and a couple of inches deeper.

If you’re working with a bare root plant, make the hole deep enough to accommodate the plant’s roots, and provide a few inches of leeway in width.

Add a handful or two of well-rotted compost to the hole; the amount doesn’t have to be exact. Then mix in some of the soil you previously removed from the hole.

For bare root specimens, wet down the roots before placing in the hole, then fill with the removed soil.

For specimens in nursery pots, ease the plant out by tilting it upside down and squeezing the sides of the pot if needed. Don’t use the plant’s foliage to pull it out of the pot!

With the plant out of the nursery pot, loosen up the roots if they are pot-bound by rubbing your hand along them.

Feel free to offer words of encouragement to the plant at this point or to sing it a little song – why not? I won’t guarantee it makes any difference to my plants when I do this, but it makes me feel better.

If any growing medium comes out from the root ball during this process, put it into the hole, mixing it with the compost and loose soil.

Situate the unpotted shrub in the hole. For both bare root specimens and those grown in nursery pots, the top of the root ball should be just level with the soil.

Adjust the amount of soil under the shrub so that the root ball is at the right level, then backfill with soil, and gently pat the soil around the plant. (Additional singing and encouragement at this point is fine too!)

Provide the snowberry bush with some water, and let the water and soil settle in.

If the soil level has sunken down considerably, add more so that the root ball is covered and at the right level compared to the ground, taking care not to bury the shrub’s crown with soil.

Finish the project off by watering the shrub one more time.

Keep the newly transplanted shrub’s soil moist as it gets established, irrigating daily if needed over the next couple of weeks.

Taper off the frequency of your waterings gradually thereafter, and adjust for rainfall.

How to Grow Snowberry Bushes

Snowberry bush is adaptable to different light conditions and can grow in full sun, part shade, or even full shade. However, it will produce the most flowers and fruit when situated in full sun.

Reflecting its widespread range, this species also grows in a variety of well-drained soil types within a pH range of 6.1 to 8.4, and tolerates poor soil, limestone, and coarse, rocky soils.

It grows exceedingly well in heavy clay soil, but doesn’t grow well in soils with lots of granite content.

Common snowberry is drought tolerant once established, and in its native range survives in some areas with as little as three and a half inches of water a year!

However, more water will provide more lush growth.

In dry climates, provide irrigation as needed until plants are established. This may mean watering daily during the warm season for the first year after planting, reducing to once a week the following year, and watering once a month in the third year – depending on your climate and rainfall.

Learn more about irrigating with our article!

Growing Tips

- Grow in full sun to maximize flowering and berry production.

- Provide irrigation as needed until established.

- Plant in well-drained, non-granitic soils.

Pruning and Maintenance

Once your snowberry bushes are planted, it’s a good idea to place mulch around the shrubs to help with water conservation.

Place a layer of mulch an inch or two thick on the soil, but leave a couple of mulch-free inches around the shrubs’ trunks. This will help prevent disease spread.

Not sure what type of mulch to use? Read our article to get the dirt on different types of mulches to use for low-maintenance gardening!

When growing native plants in their original range, fertilizer is often deemed unnecessary – the plant has evolved to be tolerant of the soil conditions in that range, after all!

And sometimes, when used with certain native wildflowers, fertilizer can actually cause the flowers to become too leggy.

However, when using snowberry bush in an intentionally designed landscape or garden setting, a balanced fertilizer can be used to encourage good growth. Fertilizer can be applied once a month from April to July.

Since this plant has a wide native range and is used to different conditions, there is not a one size fits all absolute rule when it comes to fertilizing them.

You can use a balanced fertilizer, well-rotted compost, vermicompost, or composted manure, such as this Chicken Manure Compost from Farmer’s Organic that’s available via Amazon in 22-quart bags.

Farmer’s Organic Chicken Manure Compost

To apply fertilizer, follow the instructions on the bag, or add compost by pushing the mulch to the side, mixing a couple of handfuls of compost into the soil, and replacing the mulch.

As for pruning, in a wild habitat, snowberry bushes would be pruned back by the hungry mouths of browsers such as deer.

But in the home landscape or garden, you can fill in for the deer with a pair of garden pruners.

Prune in early spring, trimming back each stem to your desired length, and shaping the shrub as preferred.

Also, every few years, trim one-third of the oldest, thickest stems back to the ground to help rejuvenate the plants.

If a plant sends up suckers and cultivating a hedge or thicket is not what you had in mind, prune the suckers back as needed.

Learn more about pruning shrubs in our article.

Snowberry Species and Cultivars to Select

If you’re looking for the straight species, the one we’ve described so far in this article, you want to ask for “common snowberry” or Symphoricarpos albus.

Species plants are available from Nature Hills Nursery.

You can also find a one- to two-year-old live plant shipped either bare root or in a nursery pot, depending on the season, available via Amazon.

When looking for the straight species locally, you’ll have the most luck finding S. albus at garden nurseries that specialize in native plants while hybrid cultivars tend to be more widely available.

Here are a few options to consider:

Magic Berry

‘Magic Berry’ is a Symphoricarpos hybrid that produces pink-colored berries in midsummer that deepen to burgundy in fall.

2-3 Year Old ‘Magic Berry’ Live Plant

You’ll find ‘Magic Berry’ available to purchase as a two- to three-year-old bare root plant or in a 3.2-gallon nursery pot from Nature Hills.

Sophie

Another Symphoricarpos hybrid, ‘Sophie’ is more compact than the straight species, reaching only three to four feet tall and wide at the most. Berries develop in fall and are dark pink in color.

2-4 Year Old ‘Sophie’ Live Plant

‘Sophie’ can be found for purchase as a live two- to four-year-old plant in a 1.5-gallon nursery pot from Nature Hills.

Variegatus

‘Variegatus’ is a variegated cultivar of S. albus. It’s more slow-growing than the straight species and has beautiful, white-margined leaves.

Can’t get enough multi-colored foliage? Discover a selection of 23 different variegated shrubs in our article!

Managing Pests and Disease

Common snowberry is considered resistant to deer – not that they won’t eat it, but the plants will bounce back well after a bit of browsing.

In fact, this species is considered an important browse for deer, antelope, and bighorn sheep. Just be careful to protect young specimens from deer until they are established.

Want to keep deer out of your yard or garden altogether? Learn how to install deer fencing.

Insect pests don’t tend to be a problem for this species. Various types of sphinx moths and leaf miner moths (Phyllonorycter spp.) can use this species as a larval host, but any damage they cause often goes unnoticed.

And remember, if you are growing this species as part of a native tree and shrub landscape, providing native insects with food and habitat is actually part of the goal. This should be celebrated rather than treated like a problem.

Diseases are not common with S. albus, but when they do appear, the most commonly encountered are leaf spot, rust, powdery mildew, and berry rot.

Best Uses of Snowberry Shrubs

Not sure how to best use snowberry bush in your landscape or garden? There are so many different options!

Let’s talk about practicalities first.

Because of their deep roots, these shrubs are an excellent choice to help stabilize banks along rivers, creeks, or streams. And since snowberry bushes are moderately tolerant of flooding, they can even be used in flood plains.

Likewise, because of their moderate flooding tolerance, snowberry bushes can be incorporated into rain gardens.

These shrubs are also an excellent choice for sites that are in need of restoration or that are prone to fire – they’ll resprout from their rhizomes after a fire occurs.

Planted densely, snowberry bushes can also be mass planted to form a border, privacy screen, or hedge.

If one of the goals of your gardening endeavors is to create habitat and food for wildlife, snowberry is a brilliant choice, and it can be used in butterfly gardens, pollinator gardens, and native plant gardens.

Snowberry bush’s branches provide good habitat for birds and small mammals, and its berries will provide a food supply for birds all winter long.

Of course, the berries also provide fall and winter interest in the home landscape, and they may be what drew you to this plant in the first place!

When companion planting is a goal, look to the species this shrub grows among in its native range.

Good shrub companions for snowberry bush include bearberry (Arctostaphylos uva-ursi), mock orange (Philadelphus spp.), creeping Oregon grape (Berberis repens), ninebark (Physocarpus malvaceus), red osier dogwood (Cornus sericea), and Wood’s rose (Rosa woodsii).

As for trees, consider deciduous trees like Douglas hawthorn (Crataegus douglasii) and thinleaf alder (Alnus icana), as well as evergreens like curl leaf mountain mahogany (Cercocarpus ledifolius), Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii), ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa), subalpine fir (Abies lasiocarpa), and western hemlock (Tsuga heterphylla).

Also, Idaho fescue (Festuca idahoensis) is a type of small bunching grass with a beautiful bluish hue that makes a good companion plant, visually as well as ecologically!

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Deciduous shrub | Flower/Foliage Color: | Pinkish white/bluish green |

| Native to: | North America | Maintenance: | Low |

| Hardiness (USDA Zones): | 2-7 | Tolerance: | Clay soil, deer, drought, dry soil, erosion, fire, flooding, poor soil, pollution |

| Bloom Time: | Late spring or early summer | Soil Type: | All except granitic soils |

| Exposure: | Full sun, part shade, full shade | Soil pH: | 6.1-8.4 |

| Time to Maturity: | 2-3 years | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Spacing: | 2-6 feet | Attracts: | Bees, birds, butterflies, small mammals, songbirds |

| Planting Depth: | 1/4-1/2 inch deep (seeds), root ball level with soil surface (transplants) | Companion Planting: | Bearberry, creeping Oregon grape, curl leaf mountain mahogany, Douglas fir, Douglas hawthorn, Idaho fescue, mock orange, ninebark, ponderosa pine, red osier dogwood, subalpine fir, thinleaf alder, western hemlock, Wood’s rose |

| Height: | 2-6 feet | Uses: | Bank stabilization, butterfly gardens, hedges, mass planting, native plant gardens, pollinator gardens, rain gardens, screening, site restoration, wildlife gardens |

| Spread: | 2-6 feet | Order: | Dipsacales |

| Growth Rate: | Moderate to fast | Family: | Caprifoliaceae |

| Water Needs: | Low | Genus: | Symphoricarpos |

| Common Pests and Disease: | Leafminers, sphinx moths; berry rot, leaf spot, powdery mildew, rust | Species: | Albus |

Snow White Awaits You

Ready to bring this beauty to life in your yard?

You should now know exactly how to get started with growing your snowberry bushes, and you’ll be prepared to keep them happy and healthy. And feel free to whistle while you work!

What’s your motivation for growing these lovely shrubs in your landscaping? Are you exhilarated by their snow white berries?

Is creating wildlife habitat your main motivation? Or do you have some other personal connection with these plants?

Feel free to share your stories in the comments section below – and let us know if you need any help while you’re there!

Need more shrub-related landscaping guidance? We’ve got plenty for you right here:

This is so helpful. Thanks!

Thanks for letting us know you found the article helpful! Happy gardening!