Is there anything like a soft, honey-sweet persimmon fresh off the tree? If there is, I haven’t found it yet.

Now, is there anything more heartbreaking than when you wait throughout the year for your anticipated harvest, only to be disappointed by bare branches? It’s devastating.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

I’ve always found persimmons to be tougher and more reliable than some other fruit trees, but that doesn’t mean that they’re without any problems at all.

There are a number of things that can cause your persimmon to fail on you.

Some problems you can control to some degree, like the amount of water they receive, and some you can’t, like the age of the plant.

I won’t keep you in suspense. Here are the nine most common causes, which we will cover in full detail, coming right up:

Why Is My Persimmon Not Fruiting?

Persimmons belong to the Diospyros genus, a name which means “God’s fruit” in Greek. And the fruit of the gods they are.

Persimmons are grouped into Asian (D. kaki) and North American native species (D. virginiana and D. texana).

It’s the Asian types that you’ll find in the grocery store. Only specialty retailers will carry the North American fruits during their short growing season.

Native types tend to fruit irregularly and they’re more astringent until they reach peak ripeness. Once ripe, though delicious, they don’t transport well.

I’ll also note that persimmons generally don’t need fertilization, and unless you’re really overfeeding, available nutrients shouldn’t be the cause of a lack of fruits.

Regardless of which species you are growing, most of the following causes can impact both types. We’ll call it out if that’s not the case. Ready?

1. Age

Sometimes we may forget that trees grow old, and they stop being able to get up from the floor without some seriously creaking knees and the help of a nearby chair.

Wait, that’s what happens to me as I age.

When these plants age, they stop trying to reproduce, and that means no more flowers or fruit.

Asian types remain productive for about 70 years. Native species can keep producing for over 100 years.

On the other end of the spectrum, trees younger than nine years aren’t fully mature and might not be ready to produce fruit. Around this age, the specimen might start blooming and setting fruit, but then some or all of the fruit will fall to the ground before it matures.

Don’t worry, it’s not your fault. It’s just the persimmon figuring everything out.

If your specimen is getting old, the only thing you can do is replace it. For younger plants, just keep waiting. You’ll have fruit soon enough.

2. Bad Genetics

Sometimes trees just have bad genetics. If you purchased a plant from a reputable nursery, then this isn’t likely to be the issue.

But if you propagated a wild cutting or took one from an older orchard, it might just be that the tree isn’t a good producer.

One of the surest signs, assuming the tree is in full sun, is that it will produce just a few blossoms, usually only on one or two branches. It’s like it’s trying to do its job right, but it just can’t seem to manage.

It might do better the next year, producing more blossoms and maybe even some fruit, but the year after that, it’s back to the same paltry performance.

These specimens can either be culled, or you can field graft a more productive performer onto the tree.

If you’re really determined to give it a chance, prune off less productive branches and retain the ones that are doing well. This should be done over several years.

3. Gender

If your tree has produced fruit before, go ahead and skip this section. But if you just planted it or you inherited one on your property, you might never have seen the tree set fruit.

If that’s the case, it’s possible that your particular plant is male.

Most persimmons are monoecious, meaning male and female flowers are produced on different trees. Males pollinate the females, so they flower, but they don’t produce any fruit.

Male trees usually have smaller flowers that are borne in small clusters. Female flowers are single and they’re larger.

There are other differences that are a little bit more challenging to identify, but you’ll be able to pick out a male versus a female tree quickly using these descriptors.

Now things are about to get a little bit more complicated.

These trees may have both male and female parts (known as dioecious), with all of the flowers containing pistils as well as sterile stamens. Or, a female specimen can produce a male branch.

On top of that, a tree can change its sexual expression from year to year. That means a female might not produce one year because it is producing male flowers in the current year.

There’s nothing you can do about a gender conflict. If you have a male tree, you’ll have to plant a female one as well if you want fruit.

4. It’s an “Off” Year

Many trees are prone to what we call alternate bearing, which is when you see a large crop one year and hardly anything the next.

Persimmons, and especially American types, are particularly prone to alternate bearing.

If you had a bumper crop last year and you’re disappointed with what you’re seeing this year, don’t give up hope. Next year might be a banger.

Alternate bearing can be caused by the tree changing its sexual expression (see: gender) or simply because it is the genetic nature of the tree to use all its energy producing persimmons one year and to not have enough energy to do as much the following year.

5. Lack of Pollination

When it comes to pollination, we group American persimmons according to the number of chromosomes they have.

Those with 90 chromosomes don’t need a pal for pollination, but those with 60 chromosomes do.

All Asian types have 90 chromosomes and thus are self-fruitful, as are the American cultivars ‘Deer Magnet,’ ‘Dolly,’ ‘Early Golden,’ ‘Killen,’ and ‘Lehman’s Delight.’

Unless you grow a self-fruitful type, you’ll need a second one to pollinate, and it needs to be an American type – not an Asian type.

You can also graft a male scion onto a female specimen to provide pollination, but be aware that the tree might reject the addition in a process known as self-pruning.

While it’s best to have one male growing for every four or so females, two females can sometimes pollinate each other since they often produce male limbs.

One of the nice things about persimmons is that they flower later in the season, so they avoid the late-season frosts that can destroy blossoms on other fruit trees like peaches, cherries, and plums.

But if you have heavy rains during the flowering period, this might prevent the male pollen from reaching the female flowers. In that case, you’re kind of out of luck that year.

6. Lack of Sun

Persimmons fruit best in full sun, though the American species will usually fruit even in part shade.

Take a look at your tree throughout the day and see how much sun is hitting it. If it is receiving more than six hours of sunlight per day, it should be receiving enough to produce tasty persimmons.

If it isn’t getting that amount of sun, you’ve got a tough decision to make. Either prune any nearby trees that are creating the shade, or you can try transplanting your tree if it’s young.

An older specimen that is in too much shade makes a nice ornamental, but it won’t magically start producing.

7. Leaf Spot

Leaf spot actually causes the fruit to abort rather than causing no fruit to form at all. If you had developing fruits but they started jumping ship, take a look at the foliage of the plant.

If you see black spotting on the leaves, it’s possibly anthracnose, caused by the fungus Colletotrichum horii.

This disease is more common in Asian types of persimmons, and it can be bad news. On the bright side, it’s not very widespread – yet – so the chances of contracting it are slim but not impossible.

If it does infect your trees, the twigs, fruits, and young leaves will show black or dark brown spots. Older leaves and fruit will drop off the tree.

The disease can be treated, but you’ll need to treat the tree repeatedly to truly eliminate it.

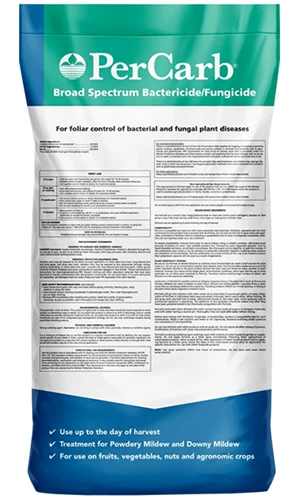

A product that contains the beneficial bacteria Bacillus subtilis is effective on its own, but it will be even more effective if you rotate it with a second fungicide like PerCarb®, which uses hydrogen peroxide and sodium carbonate to kill off the fungus.

To pick up a 50-pound pail of PerCarb, visit Arbico Organics.

While you’re there, you can also grab some CEASE, which contains B. subtilis.

Arbico Organics carries this product in one-gallon or 2.5-gallon containers.

Use one following the manufacturer’s directions and then wait until the appropriate reapplication time to use the other. Keep swapping back and forth for the entire growing season.

The following spring, apply CEASE as a preventative.

8. Over- or Underwatering

Persimmons, particularly American types, are pretty tolerant of drought. But extended periods of drought can also cause stress and a lack of fruiting.

Overwatering can cause root rot, and the stress that results due to this condition can lead to a lack of fruiting as well.

Both of these conditions can also cause forming fruit to abort.

You want to add water when the top few inches of soil dry out, but never water if the soil feels soggy or wet. When in doubt, err on the side of too dry rather than too wet to prevent issues.

9. Pruning Problems

Gardening well is all about learning and gaining experience, and we all make mistakes along the way.

I say this so you won’t judge me when I tell you that when I had my first mini orchard, I pruned all my fruit trees the same way at the same time.

I know, rookie mistake.

Some fruit tree species produce on old wood, and some need new growth.

If you prune off the new growth on a tree that needs new wood to produce, it won’t be able to give you a crop that year.

Persimmons are a bit of a challenge in that they do best when they’re pruned, but you also need to leave new wood in place for fruiting. It’s a delicate balance.

If you opt to avoid pruning altogether, your tree will produce fine, but not as well as it could. That’s because old growth is brittle and tends to break easily, plus a lack of pruning means less new growth.

But if you over-prune, on the other hand, you’re removing the growth necessary for an abundant harvest.

Persimmons fruit on young wood, so if you’re consistently cutting off the new growth, you probably won’t see much, if any, fruit.

Try to be restrained in your pruning and remove only dead, diseased, or deformed branches.

If your specimen starts dwindling in production, you can prune it back to encourage new growth. You might not have a good harvest the year you do this, but the following years should look better.

You’re Going to Need a Big Basket for Your Harvest

Don’t you hate it when someone says that a plant is normally reliable and rarely has such and such a problem? It makes me feel like a failure when my plant struggles.

So let me reassure you that though persimmons are usually good producers, and I consider myself an experienced grower at this point, I’ve run into issues before.

Sometimes it was my fault, and sometimes it wasn’t. That’s the nature of working with nature.

So what kind of problem are you having? Let us know what you’re dealing with and how you plan to tackle it in the comments. And if you need more help, don’t hesitate to ask.

Have you been bitten by the persimmon bug? Want to learn more about them? You might be interested in the following guides: