Prunus spp.

I love fruit trees, but some years I stand underneath my apples full of codling moth larvae or my peaches that never fruited because a late frost killed all the buds, and I fantasize about mowing them down with a chainsaw.

Not plums, though. They’re my reliable, easygoing, happy-go-lucky companions.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

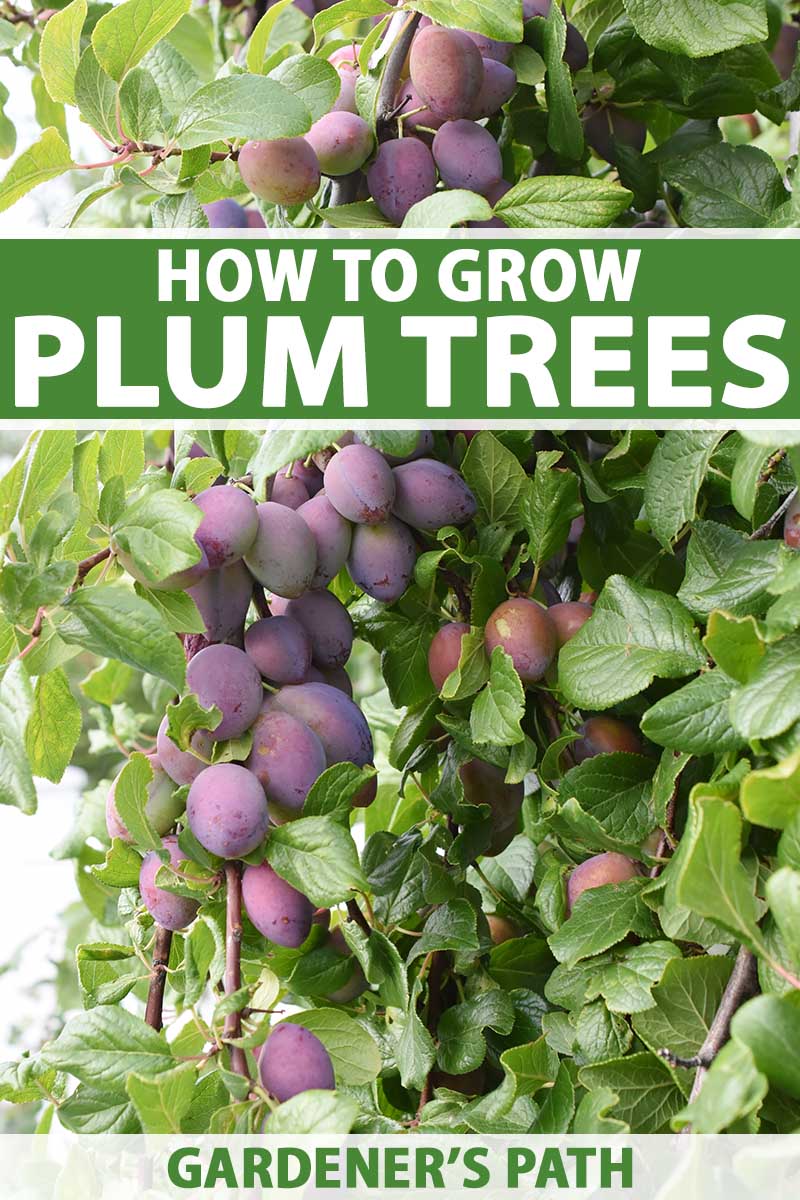

Plum trees come in teeny-tiny dwarf sizes and towering, 40-foot-tall options. Some grow sugary sweet, juicy fruits and others have petite, tangy ones.

In other words, if you want options, you’ve got options.

The showy spring display of pink, white, or purple blossoms is just a bonus. But for ornamental plums, it’s the main focus. That should tell you how pretty the blossoms can be on the fruiting types.

To help you grow bushels and bushels of flavorful fruits, here’s what this guide will cover:

What You’ll Learn

Plums are broadly categorized as either Asian (P. salicina), European (P. domestica and P. cerasifera), or hybrid.

Some people add North American indigenous types, like P. americana, P. nigra, P.angustifolia, and P. maritima, to the mix.

The pruning requirements differ slightly depending on which type you’ve got, but growing each of these is otherwise similar.

Most plums aren’t self-fruitful, and this is where the species is important. A European plum can’t pollinate an Asian one, so if you want fruits, you usually need to grow two cultivars of the same type. Don’t worry, we’ll explain all that in a minute.

The exceptions are the few cultivars like ‘A. U. Amber’ and ‘Methley,’ which are self-fruitful – so don’t give up your plum dreams if you only have room for one tree.

Cultivation and History

P. domestica originated near the Caucasus Mountains and has likely been in cultivation for nearly 2,000 years. Ancient Romans cultivated the trees in their gardens.

Plums were gradually brought by settlers from western Asia to Europe and eventually North America.

Our earliest record of prunes in the region comes from Prince Nursery, which was established in Flushing, New York, in 1737. In their 1771 catalog, they advertised 33 different plums for sale.

Asian or Japanese plums, which originated in China along the Yangtze River Basin, were introduced into Japan and later South Africa, the Philippines, the West Indies, and Australia. They reached North America in the 1800s.

These days, the vast majority of plums grown commercially in the US are found in California, but they can grow in pretty much every state, in USDA Zones 4 through 9.

There are also ornamental plum species that are grown for their extravagant spring display. They will produce small fruits, which are technically edible, but they have large pits and only a little bit of flesh.

We’re going to focus on the edible ones in this guide.

Plum Tree Propagation

You need to plan ahead when planting plums. The soil pH should be around 6.0 to 6.5, and if it isn’t, you’ll want to start adjusting the pH the year before you plant.

Test your soil well ahead of planting.

It’s entirely possible to grow a plum tree from the seed that you’ll find inside the center of the pit. However, this works best with native species rather than European or Japanese types.

That’s because European and Japanese types are less likely to produce fruit, or to produce fruit that is similar to the fruit that you got the pit from.

Most of the fruits you get from the grocery store weren’t grown from seed, they were grown on plants that were grafted. That means there’s a lot of unique DNA in there, and who knows what will pop out on your new specimen.

Planting seed is a fun activity for the family, but it’s not the way to go if you are serious about propagating a productive tree.

From Cuttings

Rooting a cutting is a good way to reproduce a plant that you love. Whereas seed propagation is unpredictable, a cutting will give you an exact clone of the parent.

In the winter when the weather is dry and the tree is dormant, take a cutting from a young branch that’s about the diameter of a pencil. The cutting should be about six to 12 inches long.

Cut the base at a 45-degree angle. This helps to remind you which side is down, makes it easier to slide the cutting into the soil, and increases the surface area.

Dip the end of the branch in rooting hormone. You can skip this step, but it tends to improve rooting.

Rooting hormone powder is pretty cheap, and if you plan to take more cuttings in your gardening journey, it’s worth having around.

Bonide Bontone II Rooting Hormone

Pick up Bontone II Rooting Powder in a 1.25-ounce bottle at Arbico Organics.

Place the cutting in a six-inch pot filled with potting soil so about a third of it is below the soil line.

Water the soil well and place in an area with bright indirect light. Maintain soil moisture as needed.

Once the cutting starts to develop new growth, gradually move it to a sunny spot outdoors, assuming there’s no risk of frost.

Harden it off first over the course of a week, adding an hour of sun exposure each day.

When there are at least four new leaves, you can transplant your rooted cutting into the ground.

Transplanting Bare Roots

Plum trees are often sold as bare root specimens.

If you purchase a bare root specimen, when it arrives at your house, open the package and check to make sure the roots are still moist. If they aren’t, add water.

Keep your bare root in an area where it will stay cool, but not freezing and not hot, out of direct sunlight. Before planting, soak the roots in water for two to four hours.

When you’re ready to transplant, follow the directions for planting a potted tree as described below.

Transplanting Potted Nursery Plants

Place trees about 20 feet apart, depending on the type and its mature size. Prepare the soil by digging three times as wide and about as deep as the container.

Work lots of well-rotted compost into the excavated soil and remove the plant from its container. Gently tease apart and loosen up the roots in the rootball.

Lower the root ball into the hole and fill in around it with the mixed soil. Water well to settle any air pockets, and add more soil if necessary.

Bare roots can be spread over a mound of soil in the hole.

Most modern plums, if they’re not own-root, are grafted onto peach or myrobalan (P. cerasifera) rootstock. The graft should be sitting just above the soil line when you transplant.

Water in your transplants. While older specimens are able to withstand some drought, younger trees can’t. They need regular and consistent water.

How to Grow Plum Trees

Location is extremely important when siting plums.

For instance, if you live in Zone 7 or below, avoid placing your trees against a south-facing concrete or brick wall.

The heat reflected off the wall can encourage the trees to flower early, which leaves them exposed to blossom-killing frosts.

Ideally, you’d plant on the upper area of a gentle slope, but not all of us have such perfect conditions. You should avoid low-lying areas, which tend to be colder and wetter than higher areas.

Most plums do best in full sun, but some can fruit even in partial sun. Plant your trees where they’ll receive at least six hours of sunlight per day.

Young specimens should be kept moist, and the soil shouldn’t be allowed to dry out at all. Older trees are more tolerant of dry conditions because they develop an extensive root system to access water in the ground.

Add water during an extended dry period or when the top three to four inches of soil are totally dry. Don’t wait for the foliage to start wilting before you think to add water.

By that point, the tree is already stressed, and this will make it more susceptible to pests and diseases.

Six months after planting, start your feeding routine. Give them a 10-10-10 NPK granular fertilizer spread evenly inside the dripline. Water the granules in after application.

The following year, feed in early spring and again in late summer. After the tree reaches maturity, you don’t need to fertilize unless you test the soil and find it’s extremely deficient.

However, heaping well-rotted compost around the tree but not touching the trunk is always welcome.

When growing in alkaline soil, Prunus species are prone to chlorosis, making water and regular fertilization essential.

Keep weeds away from inside the drip line. These can harbor pests and disease pathogens and compete with the tree for nutrients, especially when it’s young.

In the event of a late blossom-killing frost, there generally isn’t much you can do to protect your trees.

However, if you have just one or two trees and you have some of the old incandescent Christmas lights, you can wrap them in these and turn them on during cold nights to protect the blossoms.

Fluorescent bulbs won’t work, however, since they don’t generate as much heat.

So long as the blossoms aren’t killed off by frost that year, you should start seeing fruit about three years after transplanting.

Speaking of fruiting, these trees are reliant on pollinators to produce fruit.

Because they bloom for such a short period in the spring, if you have an extremely wet or windy period while they’re in bloom, flying pollinators like bees might not be able to do their job.

If that happens, you might not get any fruit that year or the crop will be much smaller than normal.

As with all stone fruits, plums need a certain number of chill hours to produce a harvest. Chill hours are when the temperature is between 32 and 45°F during the dormant season.

Broadly speaking, European plums need about 400 chill hours while Japanese varieties need over 700.

North American native types usually need fewer chill hours, and some hardly need any at all. Chickasaw plums, for instance, only need about 200 chill hours.

Growing Tips

- Protect trees from blossom-killing frosts by planting them on the upper part of a slope and away from heat-reflecting walls.

- Keep young specimens watered well; older ones can tolerate some drought.

- Feed young trees twice a year with a balanced fertilizer.

Pruning and Maintenance

Plums need special pruning to keep them productive and to avoid disease.

European plums should be pruned into a central leader shape and they don’t need aggressive pruning once they’re older.

Japanese varieties are pruned into a vase shape and require more pruning.

American types don’t need to be shaped, though you should remove about a fifth of the older branches each year to encourage young growth.

Whatever variety you’re growing, always remove any dead, diseased, or deformed branches when you see them.

European and Japanese types should be thinned just after the fruits form. You should leave one fruit spaced every four inches.

For tips on how to prune plums, check out our guide.

Another important and often forgotten part of plum maintenance is removing the fallen fruit. Not only does this fallen material have the potential to harbor pests and pathogens, but it can make a slimy mess that presents a slipping hazard.

Also, bear in mind that rats love fallen fruit. If you don’t clean it up in the fall, you are inviting rodents into your yard (and potentially your home).

Plum Tree Species and Cultivars to Select

European types tend to have a vase shape and produce sweeter fruits.

Almost any European type can be used to pollinate another European type, and these all bloom a week or two after Asian and American types.

Japanese types have a more round, open form, and they produce larger fruits. Pretty much any American or Japanese type can be used as a pollinator for a Japanese species.

American types tend to be more shrub-like and these are the hardiest of the three, able to withstand colder conditions. The fruits are also the smallest.

Most American types available for sale are hybridized with a Japanese tree, though you can find a few non-hybrid cultivars.

Not sure what type to plant? Take a look at these recommended varieties:

American

While they can vary in size, most American plums grow to about 20 feet tall and produce heaps of small, one-inch fruits.

These fruits aren’t as sweet or juicy as those of other species, but they’re delightful nonetheless. If you like making fruit leather or jams, they’re a fantastic option.

Many people simply grow them for their ornamental value. They produce masses of showy blossoms that blanket the tree in the early spring and they smell heavenly.

The reddish-purple fruits are a colorful addition to the yard even if you don’t eat them. And don’t worry – quail, turkeys, and lots of other wildlife will snack on the fruits for you.

These trees will send out suckers and spread, which may be considered a good or a bad thing, depending on how you look at it. As a bonus, native plums are self-fruitful, so you only need one.

But why not plant several? You can find these available as multi-stem shrubs or single-stem trees, depending on your needs.

They make effective windbreaks, and can fill in challenging areas that other trees won’t thrive in.

Look for cultivars such as ‘Pipestone,’ ‘Toka,’ and ‘Underwood,’ which have larger fruits and a more impressive floral display than the species.

Or you can go for the old reliable species plant, which is beautiful, tough, hardy, drought tolerant, and will adapt to most soil conditions in Zones 3 through 9.

Sold? Head to Nature Hills Nursery for a two- to three-foot bare root or a live tree in a #5 container.

Brooks

My grandparents’ home was surrounded by plums, and ‘Brooks’ was always my favorite.

The blue fruit of this Italian plum sport is sweet with a tart snap to the skin when it’s young, though left to mature, it becomes a sugary delight. And the yellow flesh is smooth and flavorful.

No shade on Italian plums, but ‘Brooks’ fruit matures a few weeks before that of the parent type, and it’s just a touch more flavorful.

This tree is hardy in Zones 5 through 9, and grows to a manageable 15 feet tall.

You have to give this one a try! If you agree, visit Nature Hills Nursery to purchase a live plant in a #3 container.

Burgundy

This Japanese cultivar grows bushels of nearly black-skinned plums encasing a juicy, blood-red interior.

The pit is particularly small, meaning there’s more of that sweet flesh for the taking. Plus, it’s pretty cold-hardy for an Asian type, able to grow in Zones 5 through 8.

Harvesting is also easy on this tree because it doesn’t grow much taller than 15 feet.

Fast Growing Trees carries live plants in three- to four- or four- to five-foot heights.

Hollywood

P. cerasifera ‘Hollywood’ is ready for its turn on the stage. Not only is it beautiful, with deep purple foliage, but the rich and sweet fruits are fantastic.

This dwarf type grows to about 15 feet tall and is as useful as an ornamental as it is a fruit tree. The masses of pink blossoms that appear in the spring are well worth having around.

Hardy in Zones 5 to 9, it’s available at Fast Growing Trees in three- to four-, four- to five-, and five- to six-foot heights.

Methley

Lots of people pick 25-foot-tall ‘Methley’ because it’s self-fruitful, so you don’t need to have more than one plum tree to produce a harvest.

But it’s actually one of the most productive plum cultivars out there. And you can pair it with a friend for even more fruit!

This Japanese cultivar is disease-resistant, can tolerate drought, and will fruit even in partial sun. The branches are extremely strong and are able to support heavy fruit production.

These trees need extra spacing because they tend to spread. Don’t worry, they’ll pay you back tenfold with plenty of fruit in exchange for their greedy nature.

Snag a four- to five-foot live specimen in a paper pot at Nature Hills Nursery for growing in Zones 4 through 9.

Managing Pests and Disease

It seems like all stone fruits have a reputation for suffering from a lot of common pests and diseases.

While plums are no exception, they may be a little sturdier than their apple and peach friends. Still, there are many issues to watch out for. These are the most common:

Herbivores

Rabbits, mice, and deer will all eat the bark of these trees.

It’s not usually a problem on older specimens which can withstand a little damage, but with younger trees, a deer could devour an entire plant in a night or two.

Fencing is your best option to protect young trees, whether you place small fences around the individual itself or fence off the entire orchard. You can also set traps to capture mice, though they cause far less damage than larger critters.

When fruit is present, birds, squirrels, and other herbivores won’t hesitate to feed on your fruit buffet.

They won’t typically eat enough to make much of a difference, but it’s something worth being aware of. If you really want to protect your fruits, use netting.

Insects

It shouldn’t come as a surprise that North American native types of plums don’t attract most of these pests as readily as non-native species.

No matter which species of plum you grow, it’s always a good idea to place traps around your orchard or individual fruit trees in order to identify pests before they become a serious problem.

Pheromone traps, sticky traps, and simple observation can all help you to figure out if pests are eyeballing your trees.

Aphids and scale insects will attack plums, but they rarely cause serious problems and can usually just be ignored.

Cultivating a healthy garden environment filled with lots of beneficial insects is the best way to tackle these types of pests.

Avoid using pesticides when the flowers are present unless they’re targeted, because you run the risk of killing pollinators like bees. You should also avoid spraying in the few weeks leading up to harvest.

If your pest problems become too egregious and you should be forced to spray, we have tips here.

The following are the most common pests that you may come across when growing plums:

Apple Maggots

Depending on where you live, apple maggots (Rhagoletis pomonella) are mostly a problem on late-ripening types like ‘President’ or ‘Valor.’

Plums that ripen during the summer won’t be infested by apple maggots because the timing of the life cycle of the pest and the fruit ripening don’t coincide.

But when the timing is right, apple maggots can be the most damaging pest you’ll come across.

Closely related to cherry fruit flies, apple maggots look like tiny house flies with white banding. It’s not the adults that you have to worry about, though – it’s the larvae, which emerge after the adult flies lay eggs under the skin of the fruit.

When the maggots emerge they begin eating their way through the fruit, leaving telltale tunnels behind. These tunnels start to rot, and over time, the entire fruit rots and falls from the tree.

Control involves taking an integrated approach involving organic pesticides and trapping. Read our guide to learn all about integrated pest management.

Plum Curculios

I don’t know why, but the name plum curculio (Conotrachelus nenuphar) sounds like some cute little critter to me.

Maybe it’s because, living west of the Rockies, I’ve never had to deal with this problem in the past. But I will tell you there’s actually nothing cute about plum curculios.

These snout-nosed beetles are absolutely devastating for apples and peaches, and while they’re less of a problem in plums, an infestation is still no walk in the park. The quarter-inch-long beetles are dark brown with mottled gray and white patches.

The adult females lay eggs in the skin of the fruit where the larvae hatch and begin devouring the flesh inside.

The fruit falls to the ground, the maggots dig into the soil to pupate, and the life cycle continues.

Start watching for these pests a few weeks after the blossoms fade on your trees. You can set out sticky traps to capture them.

Pyrethroids can be used to kill the adults and neonicotinoids may be applied to kill the larvae, but these sorts of broad spectrum pesticides can cause more harm than good.

They can kill beneficial insects and upset the harmony in your garden – no judgment though if you’ve gotta do what you gotta do.

Instead, I recommend that gardeners try a multipronged approach. Head out in the early morning and shake your plum trees.

I know it sounds weird, but if you place tarps underneath them, the beetles will drop and you can scoop them up and dispose of them in soapy water.

You should also always clean up any fallen fruit as well, because that’s where the larvae live.

Then, apply a product that contains the beneficial fungus Beauveria bassiana, like BotaniGard ES. It’s available at Arbico Organics in quart or gallon containers.

This product may be used to manage a range of soft-bodied insects. It won’t kill adults, but it will kill the larvae.

Follow the manufacturer’s directions carefully and expect to reapply it several times throughout the season.

Root-Knot Nematodes

There are several species of root-knot nematodes that attack plum trees, including Meloidogyne incognita and M. javanica.

Peach root-knot nematodes (M. floridensis), another species that may infest plums, were first identified in Florida, but they have since been found throughout the United States.

These microscopic worms can infect all members of the Prunus genus, and other hosts beyond that.

They cause bulbous knot-like growths called galls on the roots that reduce the amount of water and nutrients the tree can access, resulting in diminished and stunted growth.

While an older tree can usually survive an infestation, though it will suffer reduced vigor, younger ones are more susceptible and will more than likely die.

While there are things you can do to address the problem, I’m not going to lie, the outlook isn’t great. We have a guide to root-knot nematodes to walk you through what you need to know.

Wood Borers

Tree borers are moths that lay eggs in the bark of Prunus trees. There are three main species that attack plums: the peach tree borer (Synanthedon exitiosa), the lesser peach tree borer (S. pictipes), and the plum borer (Euzophera semifuneralis).

Both types of peach tree borers are busy laying eggs during the summer while the plum borer can lay eggs in the late spring and late summer.

The adult moths look for spots on the tree where the bark has been damaged, and when they find a spot they lay their eggs there.

As the larvae emerge they tunnel through the tree. This can cause girdling, and exposes the tree to other types of pests and diseases.

Peach tree borers look a little bit like wasps. They are black and red with clear wings, while the lesser peach tree borers are black and white with clear wings. Plum borers look more like a traditional moth, with brown, gray, and cream coloring.

This is where using pheromone traps comes in handy. If you place traps near your trees, you can monitor populations and know when it’s time to get to work.

You can also be fairly confident that the pests are present if you see sap oozing out of the bark, and frass, which looks like sawdust.

Denying the moths a place to lay their eggs is the first step in preventing an infestation. You want to do everything you can to avoid damaging your trees, so prune carefully.

Don’t ever nail anything into a tree, and use caution when trimming near the base. You should also try to keep herbivores away from your trees.

Disease

It’s not unheard of for plum trees to be infected with Armillaria or crown rot, but these diseases are not nearly as common as the following:

Black Knot

Black knot is a springtime disease caused by the fungus Dibotyron morbosum (syn. Apiosporina morbosa).

It thrives in rainy, cool weather and it can be extremely problematic on plum trees. Japanese and American species are less susceptible than European varieties.

This disease only occurs when water is present and temperatures are between 55 and 75°F.

As the new shoots emerge in the spring, they’ll exhibit strange swollen areas that are pale green. After a year, these swollen areas will eventually turn into warty, elongated, black-knotted masses.

It’s not just ugly – the masses take over woody areas on the tree and reduce production and vigor.

If you’ve had black knot in your orchard recently, a product that contains chlorothalonil is highly effective at preventing disease spread when applied in the early spring.

It’s also good at controlling black knot, but no fungicide will eliminate the disease entirely.

Try Bonide’s Fung-onil, which is available from Amazon in 16-ounce containers.

Immediately pruning off any infected branches can also help to curb spread.

Or, just choose to plant ‘Obilinaja,’ ‘Early Italian Green,’ ‘Gage,’ ‘Fellenberg,’ or ‘President.’ They’re all so resistant to this fungus, they’re basically immune.

Brown Rot

Brown rot is a common foe for peach growers, but it can visit plums as well. It’s not as problematic in these plants, attacking less frequently and causing less damage.

European plums are more susceptible than other species, and trees growing in wet, warm areas are the most susceptible. When it’s present, the fungus will travel on wind and water.

This disease is caused by the fungus Monilia fruiticola and it just loves mummified fruit.

Don’t leave any rotten, dead fruit on your tree, and it will go a long way toward avoiding this issue. The fungus is also spread by pests, so avoiding infestation also helps.

If a tree is infected, the blossoms will turn brown and soggy, and the tips of the branches will die back. You’ll also see cankers on the tree.

When the fruit develops, it will have brown spotting and will rapidly rot. This can literally happen over the course of a day. The fruit might mummify and remain on the tree or fall to the ground.

The fungus that causes this disease overwinters on this mummified fruit, which is why it’s so important to clean it up in the winter.

Silver Leaf

Silver leaf is an incredibly common and contagious fungal disease caused by Chondrostereum purpureum, the spores of which travel and spread on water.

It impacts pears, cherries, apples, elms, oaks, maples, poplars, and willows. But it’s especially severe on plums.

During rainy or humid periods, it can spread rapidly. As it spreads throughout the tree, it limits the plant’s ability to transport water and reduces vigor.

As the name implies, it causes the leaves of the tree to turn silver. It’s kind of pretty, and looks like someone took a can of spray paint to your trees.

You’ll also see a darkening of the branches from the fungal structures spreading there.

Before you start seeing silvering, the tips of young branches will start to die back, but people often miss or misdiagnose this symptom.

This silver isn’t actually shiny. The pathogen just changes the way that the leaves reflect light.

If only a few branches are infected, prune them off when the weather is dry. If the disease starts to impact more than half of the tree, you’ll need to remove and dispose of it.

Avoiding silver leaf takes some planning, but it can be done. The fungus needs to find a wound or opening to infect the plant.

If you take caution around your tree when you’re trimming weeds, do your best to prevent infestations by wood-eating insects, and never prune during wet weather, chances are good you can avoid it.

Plum Fruit Harvesting

Fruits are mature sometime in the late summer or early fall. It all depends on what specific plum you’re growing and what USDA Hardiness Zone you’re in.

‘Early Golden’ might mature in early July if you’re in a mild climate, while ‘Valor’ won’t be ready until mid-October in areas with short growing seasons.

You’ll usually get around three bushels from American trees, and up to five from European and Japanese types.

In my family, harvesting takes place via child labor. My grandma paid my mom a penny a plum and my mom paid me and my siblings a nickel per fruit.

I don’t know what the going rate is today, but round up the kids and promise them plum kuchen (zwetschgenkuchen) in payment for their efforts. It’s better than cash.

The fruits should come away easily when they’re ready. The easiest way to tell if it’s time is to pick one and take a bite. Does it taste good? Harvest away!

Preserving Plums

Plums won’t last long off the tree. To extend their shelf life, don’t wash them until you’re ready to eat them. Keep them in the refrigerator crisper drawer and they’ll last for up to a week.

To make them last longer, dry them in a dehydrator – hello, prunes! Or you can make fruit leather or jam, or can them in syrup.

You can also freeze plums by chopping them and then freezing the pieces on a baking sheet so they don’t stick together.

Once they’re frozen, you can toss them in a big bag and seal them up. They will stay fresh for about six months.

Recipes and Cooking Ideas

Plums are my absolute favorite fruit for making desserts. They have just enough acidic zing to add a tangy note to contrast with all that sugar.

You absolutely can’t go wrong with a galette. If you don’t already have a favorite recipe, our sister site Foodal has you covered.

If you’re planning to go on a hike with the fam, bring plum hand pies along as a treat. Start with Foodal’s recipe and use your homegrown plums.

Or turn them into a festive cocktail with Foodal’s sugar plum recipe.

If you lack a sweet tooth like I do, plums are also excellent as a topping for chicken or pork.

My favorite way to use them is to chop them up with tomatoes, cilantro, onions, a squeeze of lime, and chilis to make a fruit salsa.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Deciduous fruit tree | Flower/Foliage Color: | Pink, white/green |

| Native to: | China, Caucasus region, North America | Water Needs: | Moderate |

| Hardiness (USDA Zones): | 4-9 | Maintenance: | Moderate |

| Bloom Time/Season: | Spring blossoms, summer/fall fruit | Tolerance: | Some drought |

| Exposure: | Full sun | Soil Type: | Loamy |

| Time to Maturity: | 8 years | Soil pH: | 6.0-6.8 |

| Spacing: | 20 feet, depending on type | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Planting Depth: | Same as growing container (transplants), graft point just above the soil, top of the highest roots just below the soil (bare root) | Attracts: | Pollinators |

| Height: | Up to 40 feet | Order: | Rosales |

| Spread: | Up to 40 feet | Family: | Rosaceae |

| Growth Rate: | Moderate | Genus: | Prunus |

| Common Pests and Diseases: | Apple maggot, root knot nematode, plum curculio, wood borer; brown rot, black knot, silver leaf | Species: | Alleghaniensis, americana, cocomilia, domestica, mexicana, salicina, spinosa |

When the Plum Tree Blooms, the Entire World Blooms

Plums are ideal for the beginner because they’re adaptable and able to tolerate some neglect.

The fresh fruits are better than anything you’ll find in the store and you can grow types that you’d never otherwise come across.

Even if you only have a small spot available in the garden, you can have plums.

Which type are you going to grow? How do you plan to use the fruits? Share with us in the comments.

There are lots more fruit trees to enjoy, and if this guide gave you the information you needed to start with plums, you might find these helpful: