Pyrus communis

Being able to grow fruit in your own home orchard for a harvest right on your own property is a fascinating concept.

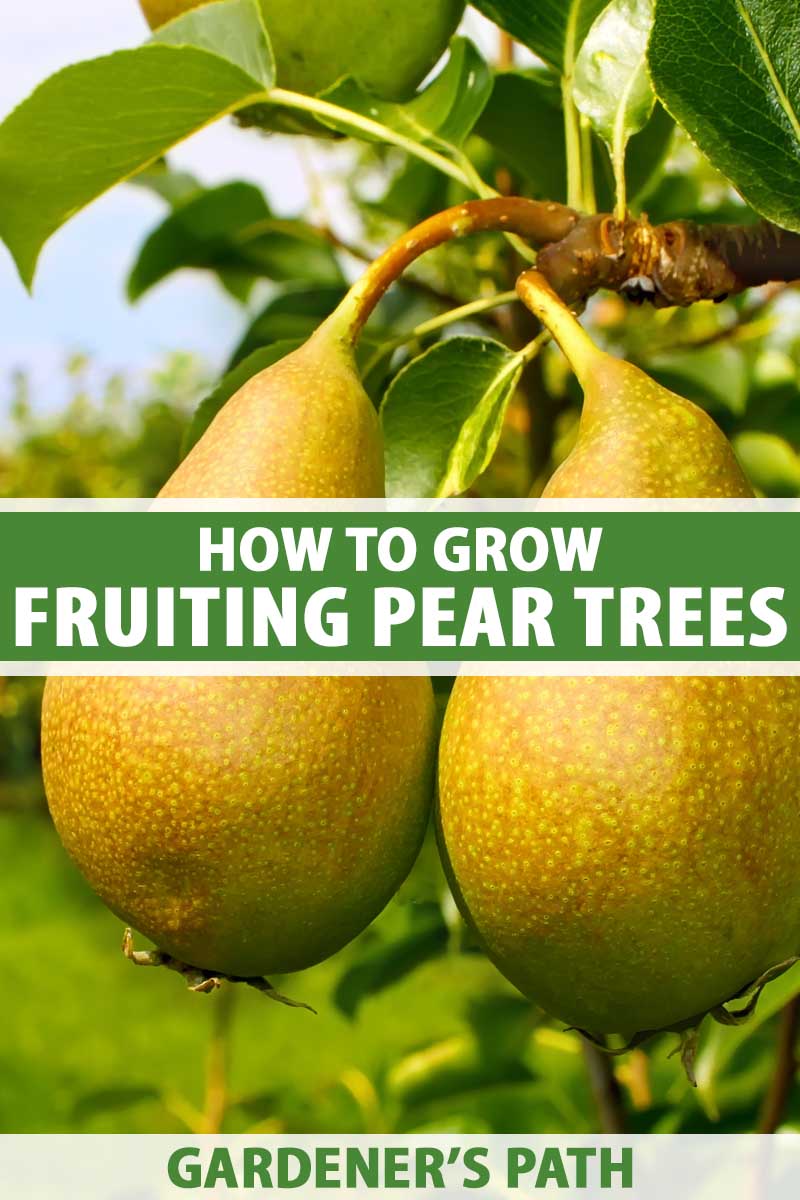

When the fruit trees in question are pears, that adds extra intrigue. For one thing, they are the rare fruit that tastes far better if you don’t allow it to ripen on the tree.

Pears are absolutely luscious picked while they are still firm, and then ripened at room temperature after harvesting.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

I also think it’s pretty amazing that most types require cross-pollination to bear fruit – but not with another tree of the same cultivar.

Instead, you must plant certain varieties a reasonable distance from a complementary cultivar – ‘Orient’ near ‘Bartlett,’ for example.

So, growing this unusual apple relative is a little different than what you might expect or be used to. Want to give it a go?

I’ll give you plenty of helpful information to get you started. Here’s what I’ll share:

What You’ll Learn

Three Types of Pear Trees

To begin, there are three main types of pear trees. They’re all related to apples and part of the rose family.

The first, and the one we’ll be talking about growing here, is the European or “common” pear, Pyrus communis.

The second type, the Asian pear, belongs to the same genus but a different species, P. pyrifolia. Native to Eastern Asia, this type has its own unique attributes and needs, and you can learn more about growing it in our guide.

Last are the ornamental pear trees. They rarely bear fruit, and some green thumbs and homeowners have a problem with the musky scent of the blooms.

One in particular, the callery pear tree, P. calleryana, is native to China and Vietnam and has beautiful white blossoms. But it’s so fast-growing it has been named an invasive species and is being phased out by law in some states.

We won’t talk about growing the ornamentals here, except to say you should be cautious when purchasing, so you don’t end up with a pretty but invasive species if you are on a mission to grow your own food.

Cultivation and History

China, Europe, and the United States are the main producers of common pears. This fruit is the fifth most widely-marketed type in the world.

And these fruits are truly ancient. According to a 2018 study published in the Genome Biology journal, the early plant ancestors of the Pyrus genus probably originated 65 to 55 million years ago, in the mountains of southwestern China.

They’re one of the fruits humans have cultivated the longest, with evidence of their growth in China dating back at least 5,000 years.

European pears have been cultivated on their namesake continent for about 3,000 years. The first specific European cultivars were recorded by name around 300 BC.

They have inspired artistic homage, from a mention in Homer’s “Odyssey,” written around 750 BC to the still lifes Medieval artists were so fond of.

The Greek poet Homer described how “pear upon pear waxes ripe” and calls them one of the “glorious gifts of the gods.”

The species made its way to the Americas with the arrival of Europeans, and at one time large-scale commercial production was common across the US.

But crop blights, particularly fire blight in the humid South, now make it impossible to grow them commercially in many areas of the US.

Six states produce much of the US common pear crop, with the majority grown in California, Oregon, and Washington, and the rest in Michigan, New York, and Pennsylvania.

The cultivars that traveled west in covered wagons in the 1800s were able to thrive in the drier and more clement growing conditions in the Pacific Northwest. Commercial production got another boost from enhanced irrigation methods that were first developed in the early 20th century.

Modern-day production in the US is centered in Washington and California, where varieties such as ‘Bartlett’ and ‘Bosc’ are grown.

Those grown in Oregon are also a big deal, with specialty orchards owned by single families for generations producing many of them.

Want to become part of this bountiful history? Read on for ways to grow these easy-care fruits yourself, even in the areas where commercial production has ceased and fire blight is still an issue.

Picking a Pear Tree to Grow and Cultivars to Select

You know how carpenters say, “measure twice, cut once”? Choosing which type of pear to grow requires the same level of careful planning before you dive right in.

First, you’ll want to make sure you’re not considering an ornamental variety that will only produce flowers, instead of an edible bounty.

Next, as mentioned before, you’ll need to settle either on the rare variety that’s self-fruitful, or plan to plant two varieties that will cross-pollinate within close proximity.

They need to be within 100 feet of each other, so a tree growing in the neighbor’s yard would also work.

Hybrid varieties such as ‘Kieffer’ will self-pollinate, but even they bear more heavily if you plant them in multiples or near another European variety.

And remember, even varieties in the same species need to bloom at the same time to boost fruit yields, so the pollinators can get their work done.

‘Orient’ and ‘Bartlett’ make a good match in this regard. ‘Orient’ trees are available from Nature Hills Nursery.

Once you’ve sorted through which varieties aid each other in pollination and which are self-fruiting, you’ll need to consider USDA Hardiness Zones.

While common pears are generally hardy in Zones 3-9, some are only able to grow in a few of the zones along that continuum.

If you live in a cold area, according to the experts at the University of Maine Cooperative Extension, you should be especially careful when selecting a variety to grow.

Only a few European cultivars are adapted to survive low winter temps like the sort you’ll experience in the winter in Zone 3 or 4. The others will die, or at least suffer damage to their limbs and roots, when exposed to harsh winter weather.

UMCE suggests these cold-hardy European varieties for Zone 4: ‘Golden Spice,’ ‘Harrow Delight,’ ‘Luscious,’ ‘Maxine,’ ‘Patten,’ and ‘Seckel.’

Also, outside the moderate temperatures and dry climes of the Pacific Northwest, fire blight resistance is a crucial element to consider.

‘Kieffer’ is popular with many who aspire to grow their own fruit, because these trees grow quickly, adapt well to both cold climates and hot, humid areas, and are resistant to fire blight.

‘Kieffer’ trees are available from FastGrowingTrees.com.

You will also need to keep in mind that pears require a number of chill hours during the winter months. This can vary from 150 for a cultivar like ‘Baldwin’ to 800 for ‘Anjou.’

For even more choices, and the pros and cons for each, consult our guide to the best fruiting pear tree varieties.

Once you’ve done your due diligence on which varieties grow best in your area, you’ll need to make sure you have a suitable spot for planting.

They need full sun, a minimum of six hours a day but preferably eight.

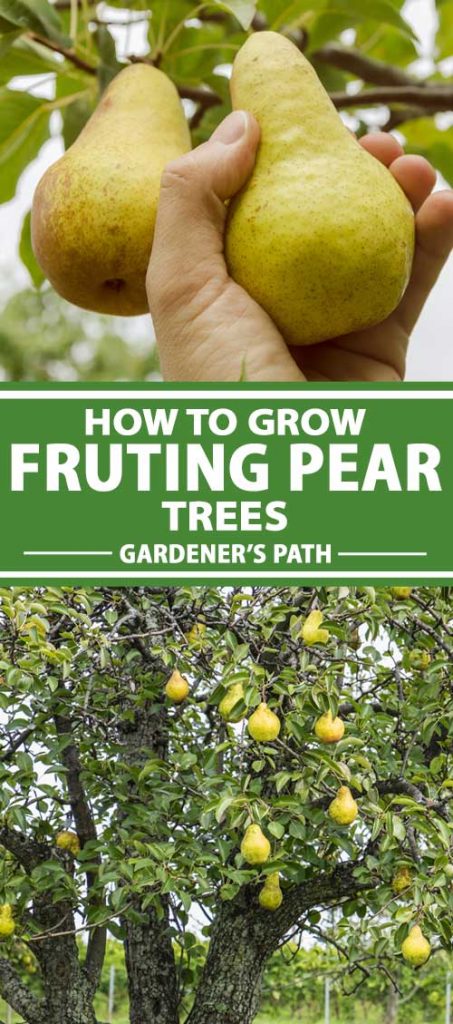

And this sunny spot will need to be spacious, since European pear trees can grow 25 to 30 feet tall and spread up to 20 feet across. Even dwarf types can grow eight to 10 feet in each direction.

One more consideration when choosing what to grow and where to plant it: these trees take anywhere from three to 10 years to begin flowering and start yielding fruit, usually hitting peak production when they’re five to seven years old.

That’s a worthy investment of time, considering the bushels you’ll pick each season after the initial wait, along with the air quality benefits and food and shelter for wildlife they provide.

While these extra tree-planting benefits are inspiring, when you’re choosing a site to plant your tree, you’ll still want to make sure you’re planting somewhere that you or someone else will be around to reap the rewards at the appointed time.

If you’re not sure about that, you may be a candidate for container varieties that can move with you to the next place. Twenty-five-foot trees are not nearly so portable.

Propagation

Saplings that you buy from the plant nursery or garden center are typically propagated by grafting or budding, which produces a clone of the parent tree.

Growing pears from seed is not recommended as it will not produce true to the parent – and will take a long time.

You can also propagate your own pear trees via cuttings, which we cover in our guide.

What Are Grafted Pears?

If you’re a veteran fruit tree grower, you can move right to the next section, because you probably already understand the grafting process.

Newbies should pause here for a few seconds to get acquainted with the concept.

Here’s how it works: Ag experts or nursery workers take a bud chip from a parent tree and physically attach it to the desired rootstock, usually of a variety that is hardier or more productive than the parent.

The two are “grafted” at this juncture, growing together as the cut to the rootstock heals.

What’s the point of grafting? It’s the most consistent way to reproduce a certain variety without losing any of its positive traits, like disease resistance or cold hardiness.

Even though it’s growing on a different type of rootstock, it is “true to name” and will bear the same type of fruit as the parent.

Most nursery-grown pear trees will be grafted, or they are the product of “budding,” where a lone vegetative bud is implanted in the wound of a rootstock and wrapped with tape until the two heal together.

Budding is a second type of asexual reproduction that creates a true to name new plant with all the characteristics of the bud.

Along with being a fascinating bit of science, it’s important to know about grafting when you plant.

You’ll need to find the inside of the curve where the rootstock and parent scion grew together, and position it away from the sun when you put it in the ground.

It’s also important not to bury the knob the graft forms, since that’s where the fruiting branches will begin their growth. They’ll need light, for sure!

If you’re ready to plant, the bit about positioning the graft is just one piece of advice that will streamline the process and increase your odds of success.

In the next section, I’ll share several more, so grab your shovel, and let’s get these pear trees planted!

How to Plant

Trees planted in the fall have several months to become established before their big spring growth spurt. You’ll also avoid the work of pinching back buds at planting time, so the tree will focus on its root system instead.

To learn more about why fall is a great time to plant trees, check out our guide.

You can also wait until late winter or early spring to plant fruiting pear trees. At that time of year, bare root trees can go in the ground as soon as the soil can be worked.

But you want to wait to plant potted trees until after your average last frost in the spring.

It’s a good idea to conduct a soil test to check if it needs any amendments. Pears aren’t super picky, but they do grow best in pH between 5.9 and 7.0.

You may need to raise the pH with agricultural lime, or reduce it with granular sulfur.

Next, you’ll need to measure before you break ground.

Whether you choose to plant in the fall or spring, you must allow 20 to 25 feet between saplings. They also must be that same distance from other trees or large areas of hardscaping.

You can get away with just eight to 10 feet between dwarf-variety saplings, but ideally you should plant them 12 to 15 feet apart.

This extensive spacing may seem a little ridiculous when you’ve got little more than an overgrown twig and a softball-sized root ball in your hands, but it’s necessary to allow for the future growth and spread of your tree.

Once you’ve picked a suitable spot, follow these steps:

- If you’re planting a sapling from a container, firmly grip the trunk and smoothly and gently ease it from the pot.

- Set the root ball on its side on the ground, then use clippers or shears to cut through any roots that have grown in a circle.They’ll need to be freed so they can seek water and nutrients in the soil instead of continuing to circle in on themselves.

- Shovel earth from a hole just a few inches deeper and at least three times wider than the freed root ball.

- If the soil is poor or average, mix it 50-50 with some organic material like well-aged compost or leaf mold. If the soil is sandy or drains too quickly, consider adding some organic compost or peat moss to help your tree retain moisture and draw up essential nutrients.

- Make a small mound of soil in the middle, and set the bare root or seedling on top. You’ll want the top of the root ball to be even with or slightly above the soil line.

- That way, water won’t pool around the trunk. This helps the soil to drain, and also protects the tree from frost or ice damage.

- Using gloved fingers, gently spread the roots out, but don’t force or bend them.

- Gently place the newly amended soil over the root ball and across the width of the hole and cover the top of the root ball with about an inch of the mix.

- Lightly firm the soil with gloved hands and water the new seedlings thoroughly.

That’s it! As the anteaters with the picnic basket said, “And now, we wait.”

How to Grow

Once you’ve planted, these trees won’t need a lot of attention from you, especially once their roots get going and before they start producing fruit.

They will need ample water during dry spells, especially in the first few months after you plant them. This will help them to establish a viable root system.

In some types of soil, they won’t require any added fertilizer.

In general, an eighth of a pound of the ammonium nitrate fruit trees love will do the trick. Apply it in early spring, even if you plant the tree in autumn.

With each passing year, add an extra eighth of a pound to the amount you apply.

You’ll be able to tell your mini-orchard isn’t getting enough fertilizer if the summertime leaves are a pale green (think inchworm-shade) or sort of yellow. If you spot those colors, use more fertilizer the following spring.

You can also apply small amounts at the end of the season to mature trees if the leaves looked yellowed instead of a nice bright or deep green.

If it’s growing too quickly, that’s also a warning sign.

More than 12 inches of growth in a single season indicates the tree has received too much fertilizer and is turning its resources to producing foliage instead of fruit, which is not what you want at all.

And you always want to err on the side of caution with nitrogen fertilizers. They can encourage fire blight, which attacks the young, green shoots that over-fertilized fruit trees produce in abundance.

Growing Tips

- Space full-size varieties 20-25 feet from other trees and dwarf types eight to 10 feet.

- Plant tees in a location that will receive at least six hours of direct sun each day.

- Make sure to water them thoroughly as soon as you plant the seedlings, and keep them well-watered during dry spells.

Maintenance

About the only other thing you need to do to keep these easy-to-grow trees happy is to prune them lightly every year. This will help them grow in a more attractive, fuller shape, and also make them more productive.

To learn how to prune your pear tree, check out our guide.

Rake up any fallen fruit and leaves in autumn to prevent disease and pests. Happily, both types of debris make a fine addition to compost if you haven’t used insecticide.

Also pick up any rotting fruit during the harvest season to keep wasps at bay.

To encourage larger fruit, you can pick some of the early, immature fruits from the branches when they are still small.

Winter is prime time for pear tree damage. Consider placing plastic tree guards in early winter to deter deer and voles from noshing on the bark.

You can learn more about preparing fruit trees for winter here.

Tree wraps can also help prevent sunscald on saplings. The wraps reflect sunlight from the trunk so it won’t heat up in the winter sun and then refreeze and kill tree tissue when the sun goes down.

Managing Pests and Disease

In comparison to apples, pears are quite resistant to most types of pests and diseases. But there are still a few to keep an eye out for.

Pests

There are a handful of insects and other types of pests that may damage pear trees, including aphids, fruit worms (particularly the codling moth), mites, and scale.

Another insect pest, pear psylla (Cacopsylla pyricola) presents a problem because it is able to become resistant to insecticides.

Mature pear psylla are sap sucking insects that look like tiny 2-millimeter-long cicadas.

According to Tianna DuPont, Tree Fruit Extension Specialist at Washington State University, they can also transmit a mycoplasma disease organism to the tree which can cause the tree to decline.

The immature nymphs produce a sugary substance called honeydew and secrete it onto both leaves and fruit, which can cause a fungal growth called sooty mold.

This makes the fruit unattractive at best and inedible at worst, and hampers the tree’s growth and productivity.

Predators and parasites of pear psylla, such as brown lacewings and minute pirate bugs are one way to control these destructive insects.

Some commercial fruit tree sprays can at least minimize an infestation, and so can organic options including insecticidal soaps and treatment with kaolin clay.

You have to be careful, though, because many of the sprays that kill pests will also take out beneficial insects.

If you do opt for a chemical spray, use it right before the tree starts to bloom. Adults begin to lay eggs as pear buds start to swell, so you’ll get maximum benefit from chemical applications by spraying before they start laying.

Repeat this at least once and preferably twice before the pear tree blooms.

You’ll need to be on the lookout for bigger pests, too.

Members of the animal kingdom also occasionally enjoy plundering the sweet crop, or nibbling the bark from the trunks when food is scarce.

Deer love the fruit, rabbits may injure the saplings by eating the bark and young shoots, and voles may girdle the trunks.

Most of this damage can be controlled with tree guards or tree wrap applied in the late fall. If you have voles, make sure any barriers extend six to 10 inches into the soil so they can’t burrow beneath them.

Disease

European pears are celebrated for being easier to grow than apples, but they can still encounter a few diseases. While many are minor, a few are more serious.

Here are a couple to watch out for:

Fire Blight

The worst is fire blight, caused by Erwinia amylovora bacteria. This is the disease that literally makes commercial European pear production impossible in the southern US and other hot, humid regions.

This pathogen only attacks members of the rose family. It is aggressive and does ugly damage. It overwinters in cankers formed on dead wood.

When the weather warms, it starts wreaking havoc when the flowers start to bloom. The first indicator of fire blight is a bit weird: It makes the blossoms appear water-soaked.

Soon, the bacteria makes its way down the branches. Tissues infected with fire blight wither and die so fast you may not even realize what happened to your once-healthy sapling.

Beneath the bark of affected tissue, there’s an icky, dark, moist patch. And those same areas will ooze pale fluid if it’s humid or rainy out.

It then turns reddish-brown, like blood, as it dries. So yes, not too attractive.

The best line of defense against fire blight starts when you choose which variety to grow. Many hybrids are at least moderately resistant to fire blight, with ‘Kieffer’ being the standout, which is why it’s so popular in the South.

You may even want to think about switching from European varieties to more fire blight-resistant Asian pears if you live in an area that’s hot and humid.

You can also initiate a spray regimen with a product that contains Streptomyces lydicus, a beneficial bacteria, starting when flowers appear. Repeat the application every five to seven days until the end of summer.

But if you see that telltale moist patch, dark tissue under the bark, and dried red stuff after a few rainy days, fire blight is the culprit and you’ll need to eliminate any diseased branches.

First, prepare a mix of one-third cup of chlorine bleach (not the colorfast kind) and four cups of water. Keep it at the ready to soak your shears or clippers between cuts and after the chore is complete.

Start each cut about eight inches below the point where you’ve observed diseased tissue. You’ll need to burn the pieces you sever. Or if that’s not possible in your area, you’ll need to dispose of them in a sealed trash bag with the household garbage.

You can tell your tree has another ailment, like a nutrient imbalance or stress from a drought, if the leaves are blackened and dry but the tissue beneath the ugly area of bark is still green or maybe dry brown.

Pear Leaf Spot

Another common threat is pear leaf spot, caused by Fabraea maculate fungi. It creates dark purple spots on the fruit or the leaves, which soon start growing into brown blotches.

Good sanitation is the best way to prevent leaf spot, especially by keeping dead leaves raked up and decaying fruit collected and placed in the compost.

If it’s too late for prevention, a fungicide spray routine is the best solution for leaf spot. Start as the leaves start forming in spring and keep up the regimen through midsummer.

You may need to rotate your fungicides to avoid potential resistance.

Harvesting and Storage

Especially if you’re used to grocery store or farmers market produce presented to you in an ideally-ripened state, it can be tricky to know exactly when to harvest pears.

First of all, you want to pick them before they turn soft. Honest!

And you’ll need to study them often for the first harvest season or two. Note when they are the shape and size of mature pears you’ve purchased in the past, or when they look like the photos in cultivar descriptions – that’s when they’re ready to pick.

They may have begun to be a tad more colorful, yellow or red according to the variety, but they should be firm.

If they are soft on the tree, you can be 100 percent certain that they’re rotten at the core. And if you pick them too soon, they’ll shrivel in storage. Not very forgiving, these pears.

But the mature fruit will leave the branches without a fight, falling readily when you twist the stems. If it’s a struggle to pick, they’re probably not old enough to leave the tree.

Once you’ve picked them, they’ll ripen at room temperature. This usually takes about four or five days, but check them once a day.

It would be sad to let them get overripe, even though you can use any inferior fruit in smoothies.

Some winter pears, including ‘Anjou’ and ‘Bosc,’ need to be stored at 35-40°F for a week or two before coming out to the kitchen counter to ripen at room temperature.

Others can move straight from branch to bushel basket to a space in a room that’s consistently between 65 and 75°F.

I share this advice in a friendly manner, but I urge you to follow it. Don’t test for ripeness by taking a big bite!

Immature pears are hard and granular. I think the unripe peels taste a bit like aluminum-flavored vinyl with a hint of green cantaloupe rind. They don’t taste good.

To check for ripeness, instead of biting into a pear, first press down on the peel near the “neck” at the top. It should give a little.

Then hold the piece of fruit to your nose. If you catch a whiff of that signature sweet pear aroma, get ready to munch!

The ripe fruit will last about a week in the fridge.

You can learn more about how to store pears in our guide.

If this is your first harvest, you may want to experiment with a few pieces before picking the whole kit and kaboodle.

But you’ll quickly get a sense for when your particular variety is ready to pick, and when it has ripened to peak flavor.

Another thing to keep in mind about these fruit trees: they produce all their bounty within a short period of time.

Before they mature, prepare to pick the whole crop. You won’t have a lot of time to get ready to store, share, can, freeze, or dehydrate once they’re ready to pick.

All this fruit (perhaps literally) descending at once as a good thing if you ask me!

As long as you have plenty of containers to pick and store, and all the ingredients you need for jams, chutney, and pie filling at the ready, you can stock up within just a week or two.

For more extensive info on when pears are ripe and how to know when to harvest them, see our guide.

But stay right here for more information on preserving this harvest, along with a few suggested recipes.

Preserving

If canned pears remind you of fruit cocktail from the grade school cafeteria – and that’s not an experience you remember fondly – you can safely expect an upgraded experience when you can your own pears.

The fresh taste is something to savor, and with home canning capturing the modern imagination, there are a lot of fun recipes out there, too. Pickles, anyone?

Experiment with the many canning, jam, conserve, chutney, and sauce possibilities, but don’t try to freeze raw pears. They’re not toxic or anything, but when defrosted they turn to a tasteless mush.

They do freeze just fine inside baked muffins, though!

You can dry part of the harvest for snacks, too. Dehydrated pears that have been reconstituted by soaking in water for a few minutes can also make a tasty, nutritious addition to your favorite granola, cookie, or chutney recipe.

Be sure the ones you dry are ripe but not mushy, and peel what you plan to dehydrate, since the skins get tough during drying.

- Wash, peel, and core pears, then cut into slices or rings, 1/4 to 1/2 inch thick.

- Pretreat the slices with ascorbic acid, or a commercial fruit protector blend like Ball Fruit Fresh, available on Amazon.

- Spread the pieces in a thin layer on a suitable drying tray, whether that’s a cookie sheet, dehydrator tray, or oven-safe plates or pans.

- Dry them in a dehydrator set to 130-135°F or a 140°F oven. They should be moisture-free but still pliable when the process is complete.

- Store them in sealed bags, BPA-free airtight plastic containers, or clean, dry canning jars with new lids or reusable plastic lids.

You can also use overripe pears to make fruit leather. Just don’t use it on its own or the final product won’t have much taste, and it may be coarse or grainy.

Instead, pair the puree with other fruits like strawberries or apricots when you make fruit leather. The pears mellow the stronger-flavored fruits, and the berries or apricots add sweetness, an enticing aroma, and colorful pizzazz to the combination.

Recipes and Cooking Ideas

Fruit desserts may be the ultimate option to cook with this fruit. Consider treating yourself with an indulgent batch of citrus caramel roasted apples and pears, using this recipe from our sister site, Foodal.

They’re also good in pies, tarts, muffins, shortcakes, crisps, crumbles, buckles, clafoutis (am I starting to sound like Bubba Blue from “Forrest Gump”?)

Don’t forget to enjoy these tasty fruits, properly ripened, as an everyday treat as well. They can pump up a salad, for example, like they do in this recipe for baby greens with roquefort and pear, also on Foodal.

You can also use them to rev up the flavor in your favorite homemade applesauce recipe, substituting them for up to half of the apples. Just don’t try a 100 percent swap, or the sauce may be a little too watery or mealy for your liking.

For more recipe inspiration for your pear harvest, head to our sister site, Foodal.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Perennial fruit tree | Maintenance: | Low |

| Native to: | Asia | Tolerance: | Cold or heat, depending on variety |

| Hardiness (USDA Zone): | 3-9, depending on variety | Soil Type: | Fertile, rich in organic matter |

| Season: | Summer | Soil pH: | 5.9-7.0 |

| Exposure: | Full sun | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Time to Maturity: | 3-10 years | Companion Planting: | Basil, garlic, nasturtium, mint, onion, and tansy to deter pests |

| Spacing: | Standard 20-25 feet (12-15 feet dwarf) | Attracts: | Bees, birds, flies, wasps, and other pollinators |

| Planting Depth: | Same as root ball | Order: | Rosales |

| Height: | 30 feet (8-10 dwarf) | Family: | Roseaceae |

| Spread: | 20 feet (8-10 dwarf) | Genus: | Pyrus |

| Water Needs: | Average | Species: | communis |

| Common Pests: | Aphids, codling moth,deer, fruit-eating animals, mites, voles | Common Diseases: | Fire blight, pear leaf spot, pear psylla, powdery mildew |

Prolific Fruit Trees, Partridges Optional

These days, when so many of us are trying to grow more of our own food and create a sustainable haven for wildlife and pollinators, planting fruiting pear trees just seems like a good idea.

What about you? Have you grown these delicious fruits? Tell us about your experience to the comments section below! And if you’ve got a question, we’re here to help.

And for more information about how to grow your own fruit trees, check out these guides next:

- 9 of the Best Asian Pear Varieties for the Home Garden

- How to Grow and Care for Fruiting Cherry Trees

- Give the Gift of Fruit: How to Grow Peach Trees

Photo by Meghan Yager © Ask the Experts, LLC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. See our TOS for more details. Product photos via FastGrowingTrees.com and Nature Hills Nursery. Uncredited photos: Shutterstock.

Found info on Pears by Rose tremendously informative and will surely enhance my tree’s future. Enjoyed, and thanks.

Thanks for the encouragement, J.V.! And wishing you all the best with your pear tree.

There are really nice still life shots here for artists. Thank you!

This was an incredibly informative article. I moved into a house 2 years ago that has (2) 20’+ fruiting pear trees. I have zero idea how to care for them (and by your article, it sounds like they mostly take care of themselves, fortunately) and did not know if they were edible or if they needed to be sprayed with something. Your article answered those questions and I am very much appreciative! Now that I know they are safe to eat, I will harvest them and drop off at our local food bank. Thank you.

Thanks for reading, Jennifer!