Prunus persica

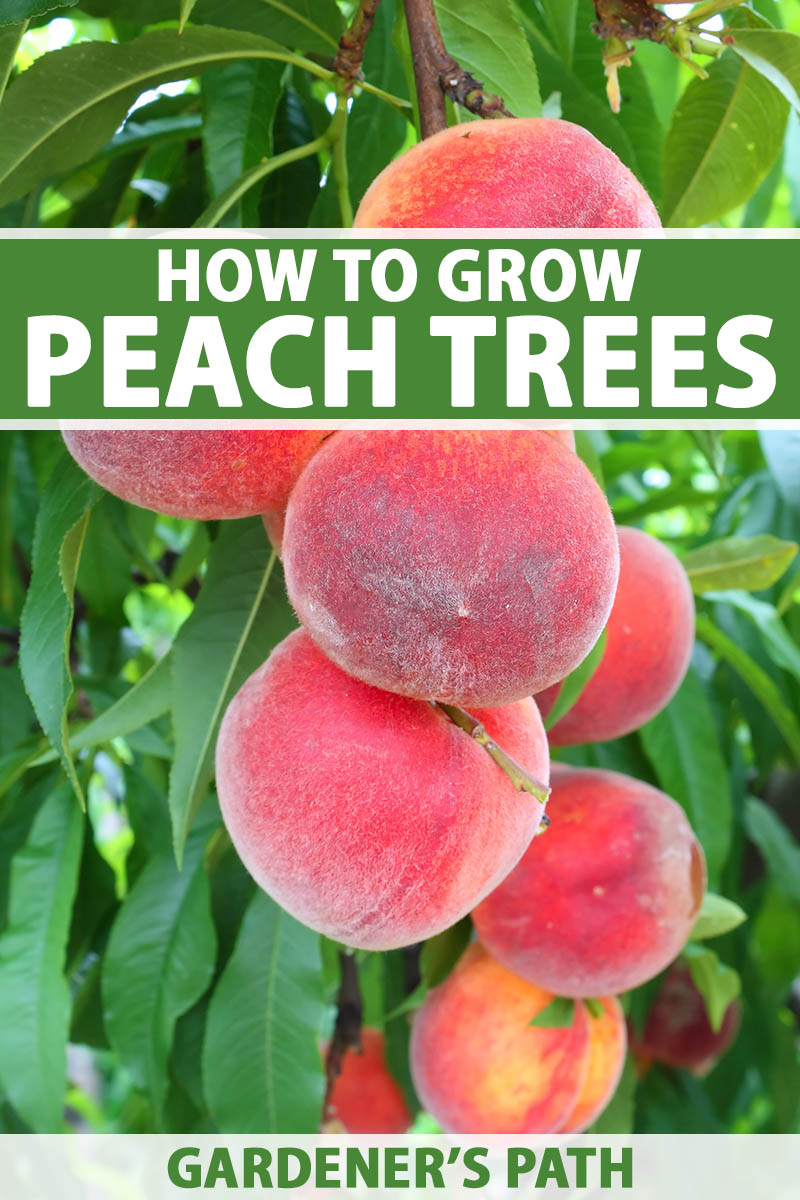

Scooch over apples, because peaches are coming for you. Apple trees are the most popular fruit tree for home growers, with peaches coming in at a close second.

Considering how difficult it is these days to find a tender, richly-flavored, juicy peach in the grocery store or even at the farmers market, I wouldn’t be surprised if more and more people start adding these gorgeous trees to their gardens just so they can get their hands on the incomparable fruits. I know that’s why I grow them.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

As much as I adore an achingly ripe fig or a blood red cherry, I can buy them at the grocery store in a pinch.

But a truly unctuous peach? Impossible to find if you don’t have access to a tree.

I’ll level with you. The rewards don’t come without a cost. Growing peaches isn’t the easiest garden endeavor you’ll ever try your hand at.

These trees are plagued by pests, diseases, hungry herbivores, and late-season frosts.

But with hardier and tougher cultivars available and a little bit of know-how, you can have homegrown peach juice dripping down your wrist in no time.

This guide will help you make it happen. To get there, we’ll discuss the following:

What You’ll Learn

Peaches will grow in Zones 4 to 9, but they do particularly well in Zones 6 and 7. Varietal selection is particularly region-dependent, and we’ll explore this more later in the article.

Peaches are self-pollinating, so while you may want to grow an orchard so all your loved ones can have bushels full, you don’t need more than one to get fruit.

But though they’re self-fruitful, you can always plant multiple cultivars to extend the harvest season. You could have fresh peaches from early spring through late summer!

By the way, if you’re trying to figure out how to grow nectarines and you landed here, most of the information in this guide applies to nectarines as well.

Nectarines are genetically similar except they lack the fuzz on the skin, and they usually have darker coloring, though not always.

Cultivation and History

The peach is a deciduous tree native to northwest China and it has been cultivated in the region for centuries.

Their cultivation has been documented dating at least 4,000 years back and genetic evidence shows that they were being cultivated thousands of years before that.

China continues to produce the majority of peaches and nectarines in the world.

The plants were brought to and cultivated in Japan around 4000 BC and India around 1700 BC.

In the wild, the trees can grow up to 23 feet tall, but cultivated trees rarely reach such heights.

Alexander the Great found peach seeds in Persia around 300 BC, and he and his armies carried them to Greece.

From there, they spread throughout Europe, and Europeans assumed they originated in Persia.

That’s actually where the specific epithet persica comes from, and the fruits were called Persian apples or plums at the time.

Peaches were brought to Florida by Spanish explorers in the 16th century, and the rest, as they say, is history.

The tree’s delicate blossoms are heralded for their beauty. These are similar to those produced by other close relatives, all in the Prunus genus – the fruiting cherries, flowering cherries, plums, nectarines, and almonds.

The half-inch to one-inch in diameter flowers bloom in various shades of orange, red, pink, and violet, and can be quite fragrant. They appear on the branches before the leaves emerge.

The blossoms can be so lovely that there are even peach trees that are grown solely as ornamentals.

And while Georgia fancies itself the peach capital of the universe – the Atlanta area in particular – California actually produces more of the fruit annually.

Peaches are a type of stone fruit (drupe), along with plums and cherries. The name describes the hard, stony covering around the seed, known as the endocarp. The fruits also contain the fleshy interior called the mesocarp, and the skin called the exocarp.

The endocarp is often used to create an almond-flavored persipan, which is a cheaper version of the almond-based marzipan. It shouldn’t come as any surprise that peaches and almonds are closely related.

The seeds inside the endocarp contain hydrocyanic acid, which is poisonous. One seed won’t kill you, but don’t eat lots of them intentionally or you could become extremely sick.

Peaches might taste like candy, but they’re extremely good for you. They contain antioxidants and anti-inflammatories like the phenolic compounds quercetin, catechins, and cyanidin.

You can loosely group the flavor of the fruits by the color of the flesh. Yellow flesh tends to be more acidic, and white flesh tends to be sweeter. The sweeter ones are sometimes called subacid types.

The trees develop their fruiting buds in the late summer, and they remain dormant until the tree experiences a certain number of cool days, which we’ll discuss in a bit.

After the extended chill, the fruit buds start to develop. The fruits must experience temperatures above 68°F to mature.

Propagation

Peaches are best propagated through cuttings or purchased plants.

While you can grow a fruit-bearing tree from a peach pit, it probably won’t be the exact same type of peach that you originally ate to get the pit.

As the product of sexual reproduction via pollen and ovules from potentially different sources, peaches will not necessarily grow true from seed.

Experiments in hybridization and creating new varieties can be fun, though this requires a lot of patience while you wait for the plant to mature.

Most commercially grown peach trees are grafted onto hardy and vigorous rootstock of related species, sometimes of dwarf varieties to contain the size of the new tree.

From Cuttings

Hardwood and semi-hardwood cuttings may be taken as a common method of peach propagation. This methods of asexual reproduction creates clones that are exact replicas of the parent.

Semi-hardwood cuttings tend to root better, but you have to keep the environment humid and they can’t tolerate wet feet. Hardwood cuttings are more forgiving but they take longer to root. It’s a sort of pick-your-poison situation.

Semi-hardwood cuttings should be taken in the early summer, while hardwood cuttings should be taken during the dormant season in late winter.

Hardwood cuttings need to be about a foot long and at least as thick as a pencil. Cut off any lower shoots and leave just two or three leaves attached at the top.

Softwood cuttings should be about eight inches long. They should be soft and newer but not green growth.

Make the cut at a 45-degree angle and place the cutting in water until you’re ready to plant it. Once you’re ready, dip the end in rooting hormone and place it in prepared soil outdoors for hardwood cuttings, or moist sand for softwood cuttings.

For softwood cuttings, the temperature must be between 55 and 77°F for rooting and the location should receive bright, indirect light or a few hours of morning sun.

Tent plastic over the softwood cuttings to hold moisture, or plan on misting several times a day. Keep the sand moist.

The soil for hardwood cuttings should be kept moist as well.

Harden off softwood cuttings in the spring first by removing the covering for a few weeks before transitioning the plants outside after the last predicted frost date. Leave the cutting outside for an hour in a sunny, protected area, then bring it back indoors.

Each following day, add an hour until the plant can be outside for a full eight hours. Then you can plant it as described below.

From Seedlings/Transplanting

Transplanting should be done in early spring when the tree is completely dormant. Any new growth is a sign that it’s too late to plant.

If you find a bargain sapling or a friend gives you one and it has new growth, don’t despair. You can plant it, but the tree will be stressed and probably won’t fruit the following year, assuming it’s old enough that it could produce fruit.

Dig a hole that’s a few inches deeper and wider than the root ball. Gently loosen the root ball and set it on a small mound of soil at the bottom of the hole, centering it in the hole.

Grafted plants should be situated so that the graft union is two inches above the soil level.

Carefully refill the hole with the soil you removed, to the same depth as the container the plant came in. If you bury more of the trunk than what was buried when you bought the tree, the plant could die.

Thoroughly water the newly planted sapling. This closes up any air gaps. Add more soil if necessary to create a smooth soil surface.

Plant about 18 feet apart for standard trees and closer to 10 feet apart for dwarf trees.

How to Grow Peach Trees

One of the biggest factors in finding success with growing peaches is in choosing the right location.

Peaches flower earlier in the spring than apples, plums, and cherries. That means that they’re more susceptible to late-season freezes that can destroy the flowers and, subsequently, your crop.

In areas that are prone to late-season frosts, like Colorado and Utah, grow peaches near a cement or brick wall to reflect some heat back onto the plant.

You can also plant on the upper parts of slopes or hills. Avoid low-lying areas, which typically experience more frost.

Choose a sunny spot that won’t be shaded at any point by other trees or buildings. Some trees can adapt to a little bit of shade, but peaches won’t produce in anything but full sun.

If you have to compromise, make sure the tree gets early morning sunlight because the sun helps to dry the dew. While dew looks pretty, it can lead to fungal disease.

Choose a spot with deep, well-drained soil with a pH around 6.5. Sandy loam is best. If you don’t have perfect soil, work in lots of well-rotted compost. Compost adds nutrients and it can loosen up clay and improve drainage in sand, so it’s the do-it-all soil amendment.

Amend the soil at least two feet deep and six feet in diameter. It’s a lot of digging, but it will pay off.

If your soil drains poorly, don’t plant peaches. There’s no way around it, these trees are too sensitive to excess root moisture, and they will rot.

In the best-case scenario, they will be stunted and perform poorly. Worst case, they’ll die.

If you didn’t add compost, scatter one cup of 10-10-10 NPK fertilizer at least 18 inches away from the trunk of newly planted trees.

Better yet, do a soil test in the fall before planting and amend your soil to alter the pH as needed. In the spring, before planting, add any lacking nutrients well in advance of planting.

A peach tree needs about 36 inches of water annually, or about three inches per month. Water is more vital during the growing season, and the tree needs less water during the dormant season.

What does that look like in real life? If you get frequent summer soakings – every 10 days or so – you may not have to do supplemental waterings once trees are established.

If, on the other hand, you live in Austin, Texas, where it only rains once or twice during the summer, you’ll need to bring out the soaker hose.

Of course, all this doesn’t help you to figure out when to water unless you have a rain gauge. These tools are affordable and extremely useful.

Water is best given infrequently. You want to water deep and less often rather than watering shallowly and frequently.

Young trees will need to be watered more often, and the top few inches of soil shouldn’t be allowed to dry out completely before watering again.

Just don’t overwater. You want the soil to feel like a well-wrung-out sponge, not muddy or soggy.

Fertilizing

Young trees up to five years of age need one pound of granulated 10-10-10 NPK fertilizer in early spring after the last predicted frost date and again in early summer.

As the tree matures, feed it two pounds of 10-10-10 fertilizer twice a year — once in early spring and again in early summer – throughout its lifespan.

I highly recommend you test your soil once a year. It’s not expensive, and it gives you important insight into your soil’s makeup. At the very least, test every few years.

If you find that your soil is deficient in a specific nutrient, add it in addition to the 10-10-10 fertilizer, unless you find the soil contains excessive nutrients. Then, you’ll need to create a custom plan according to the test results.

In some areas, iron deficiency is common. A lack of iron causes leaf chlorosis, with yellowing between the leaf veins, as well as smaller sized fruits. So it’s not something to mess around with!

Sometimes soil can have sufficient iron, but it isn’t available to the tree because of a lack of water. Keep the soil sufficiently moist to ensure the tree can access the iron. Chelated iron can increase iron levels.

Growing Tips

- Plant in full sun, preferably at the top of a sloping area.

- Trees need about three inches of water per month, with more in summer and less in winter.

- Feed twice a year with granulated 10-10-10 NPK fertilizer.

Pruning and Maintenance

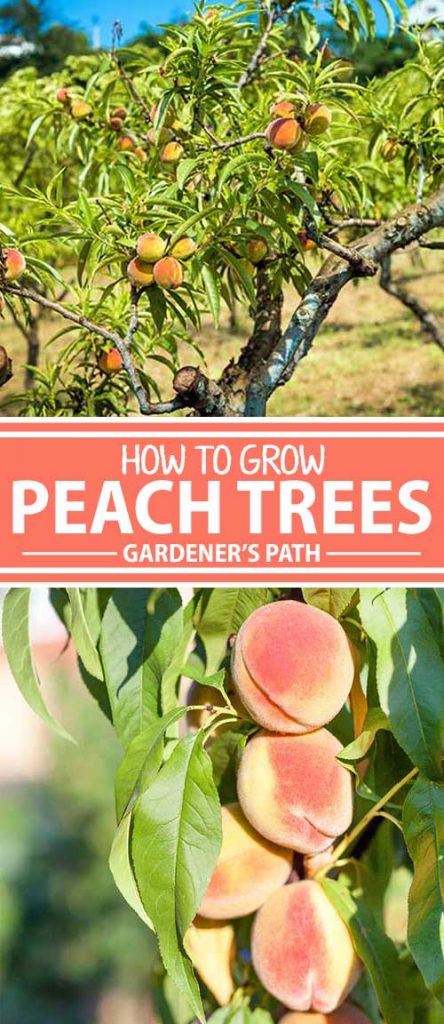

Pruning is super important. Peaches produce best when they have a vase or open center shape.

Most young trees found at nurseries are already pruned to shape, so you just need to plant and maintain the shape.

If you buy a stick-straight sapling with a few branches sticking out here and there, you’ll need to provide some shape at home.

You don’t need to do much other than remove crowded, crossing branches during the first three years of the tree’s life.

Then, in the fourth year, cut the leader (the tallest, central branch) at the nearest lateral branch or bud.

Prune any lower branches off until you have five to seven branches total. For the next two years, remove any smaller branches that try to grow.

After that, remove any water sprouts, and any diseased, broken, or crossing branches, to maintain the shape. This should be done right after your harvest, or in the dormant season in late winter.

Many peach growers trim their trees to about 15 feet or less, producing a wider tree that makes it easier to reach the fruit. If you don’t do that, get yourself a fruit picker.

Actually, get yourself a fruit picker regardless! It makes it easier to access fruits without using a ladder. The less time you spend on a ladder, the less likely you are to be injured.

Eversprout makes a fantastic option, and it’s the one I use.

The basket is padded to prevent bruising, and the basket threads on for a secure attachment that can be swapped out with other tools like compatible window squeegees. It comes in 12- and 18-foot options at Amazon.

With a tall tree, you can always use a ladder to harvest the fruit you can reach, and let the squirrels and birds have the rest.

You’ll be extremely popular with your local wildlife. Just be sure to clean up any fallen fruit at the end of the season to prevent disease and avoid supporting rat populations.

Another important aspect of growing peaches is the need – however difficult it is – to thin the fruit when they are three-quarters to one inch in diameter.

Trees naturally produce more fruit than they can carry, and if you don’t thin the branches they can break, or the peaches will be small and less flavorful.

Pluck off excess fruit so you are left with a fruit every three to five inches or so, depending on the cultivar.

You’re going to feel like you’re removing a lot, and it seem like a shame to do such a thing.

But trust me, you want your tree to devote its energy to growing the best harvest possible, rather than spreading its resources inadequately among far too many little fruits.

Toss them in the compost and just think of it as contributing to the next year’s crop.

Don’t till under the trees since the roots tend to be shallow.

Cultivars to Select

There are hundreds of peach cultivars, which can make selecting one seem overwhelming!

It always pays to chat with the experts at a local nursery or agricultural extension to learn about which ones grow well in your area. Some cultivars will thrive in the humid heat of the south, and others will do best in the cooler conditions of the northern latitudes.

It’s important to select a variety that is known to do well in your area. Peach trees have very specific chilling requirements in order to break dormancy and begin flowering.

What does this mean? Each variety needs a certain number of chilling hours below a particular temperature. For example, ‘Bicentennial’ requires 750 hours under 45°F each winter in order to bloom, whereas ‘Gulfking’ needs only 350 hours under 45°F.

If you choose a cultivar that needs fewer hours of chilling than what commonly occurs in your area, your tree might start blooming during a January or February warm spell.

And then a subsequent cold snap could kill all of your blooms, meaning you’ll have no peaches when harvest season rolls around.

You should also choose winter-hardy types if your region experiences severe freezes in late winter, which can kill the developing buds. Cultivars such as ‘Redhaven’ are known for being hardy enough to survive and produce fruits even after severe late freezes.

Sometimes, even if you have the right cultivar for your area, a late frost kills your blossoms anyway. Your best bet is to consult with your county extension agent to learn which varieties typically do well where you live.

Peaches are divided into freestone or clingstone types. Freestone just means the pit isn’t attached to the flesh and can easily be removed. Clingstones are more popular for canning and freestones are more popular for fresh eating.

Not to confuse the issue, but there are also semi-cling varieties, which are somewhere in between, though most growers don’t worry about those. They just call them clingstones.

Bonfire

‘Bonfire’ is the all-purpose tree that provides handfuls of petite peaches to anyone with just a few square feet of sunny exposure.

It’s not just about the fruit, though. Highly fragrant, double flowers drape this true dwarf in the spring, followed by bonfire red and burgundy foliage in the fall.

If you aren’t clear on the difference between a true dwarf compared to a grafted dwarf, a true dwarf is a plant that was bred (or discovered) to grow small. Grafted dwarfs are full-sized scions grafted onto dwarf rootstock.

These can sometimes revert, which essentially is when the rootstock starts to take over the scion. Suddenly, you’re growing a full-sized tree instead of the dwarf you expected.

If you’ve ever heard someone lament that their expected dwarf tree wasn’t truly a dwarf, this is what they’re talking about.

But I digress. With ‘Bonfire,’ you can enjoy an ornamental and edible peach tree even if all you have available is a small patio.

The tree reaches about six feet tall at most and just a shade more narrow. Come late summer, you’ll be enjoying red-orange peaches with white and red-striated flesh.

Just keep in mind that these aren’t the juicy, honeyed fruits you might picture when you think of peach trees. They’re firm and not as sweet, so they’re best for baking.

This cultivar requires 400 chill hours in Zones 5 to 9 to produce the clingstone fruit. Find trees in one- to two- or two- to three-foot sizes at Fast Growing Trees.

Elberta

One of the most popular peaches for home growers, ‘Elberta’ has sugar-sweet, freestone fruits with yellow and red skin, and golden yellow flesh.

Even if this cultivar weren’t pest- and disease-resistant – and it is! – it would be well worth growing this 15-foot-tall tree for the massive fruits.

‘Elberta’ needs about 800 chill hours and grows best in Zones 5 to 8. If these conditions are met, the fruits are ready starting in late July, with the pinkish-purple flowers popping out in early March.

Pick up a self-fruitful tree in a #3 or #5 container at Nature Hills Nursery and bring the original Georgia peach home.

Golden Jubilee

There’s something to be said about the firmer peaches. They travel well and resist bruising.

But sometimes you want those honey-sweet, juicy, soft peaches that can only be enjoyed straight off the tree.

The petite, freestone fruits on this 25-foot-tall heirloom are perfectly golden with a hint of scarlet blush, and they’re ready in July for your summer barbecue feasts.

‘Golden Jubilee’ needs 850 chill hours and will produce large, juicy fruits even in cooler climates. Disease resistant and quick growing, there’s so much to love about it.

If you live in Zones 5 to 8, pick one up for your garden at Nature Hills Nursery.

Hale Haven

Named for its parent trees, ‘J. H. Hale’ and ‘South Haven,’ ‘Hale Haven’ combines the best of both with a tolerance for frost and a huge harvest of large, freestone fruits.

If you’re sick to death of bruised fruits, the thick, orange-yellow skin if this variety has you covered. It’s resistant to bruising, protecting the tender carmine flesh and making the fruits ideal for canning.

After 900 chill hours in Zones 5 to 8, the fragrant pink flowers will fill your garden with floral joy. The fruits of this self-pollinating, 15-foot tree are ready for harvest in early September.

White Lady

Impatient growers, take note: Fast Growing Trees has live ‘White Lady’ peaches available in five- to six-foot heights, which means you could be eating peaches next spring.

This peach starts producing earlier in its life and earlier in the year than many other types. The pale blush and white-skinned fruits start maturing in June on a 15-foot tree.

These trees are highly productive, pest- and disease-resistant, and produce subacidic peaches with all the sweetness and little of the acidity of other types.

Better yet, you can start munching them while they’re still firm or wait for them to soften up on the tree for a juicy treat.

Managing Pests and Disease

Peaches are so incredibly delicious, and the trees themselves are beautiful. But there is a serious downside to growing peaches.

They have a higher-than-average susceptibility to disease and pests. If you don’t experience a problem, you are in the lucky minority.

Don’t let that turn you away. The bright side is that because pests and disease are so common, we’ve become pretty adept at dealing with these issues.

Some people mistake sunscald for a disease, but this is caused by winter wind and sun damage. It results in cracks, discoloration, or damage on the southwest part of the trunk.

This damage leaves the tree open to pests and diseases. If you experience this issue, wrap your trees in burlap during the winter from the soil line to the lowest branches.

We also need to note that while peaches start producing quickly, they don’t last long.

Commercial growers replace their trees every decade or so, while home garden specimens last about 20 years.

If your tree is reaching its second decade in life and you find it isn’t producing well anymore, it might just be an age issue and not any type of pest or disease.

Let’s talk about the first challenge: herbivores.

Herbivores

Squirrels, rats, and birds will eat both immature and mature peaches.

While rats are usually more of a problem with fallen fruit, they can and will climb the tree and eat or carry off the fruits. The same goes for squirrels. Birds won’t carry off the fruit, but they’ll peck at it, rendering it inedible to humans.

There isn’t much you can do about these critters except plant enough trees to satisfy your needs. Clean up any fallen fruit and use netting if you’re determined to prevent pecking.

Insects

In addition to the insects on this list, you may occasionally encounter tarnished plant bugs, stink bugs, fruit moths, and European red mites. Here are the most common and damaging pests:

Aphids

Aphids are common garden pests, and they’re especially common on peach trees.

There’s even an aphid named for their favorite source of food: the green peach aphid (Myzus persicae). Mealy plum aphids (Hyalopterus pruni) are also common.

When these small sapsuckers feed on trees it causes a host of symptoms, from curled, yellowed leaves to sooty mold thanks to deposits of sticky honeydew, stunted growth, and dropping foliage.

Dormant spray can help suppress populations, and beneficial insects are vital.

Learn more about controlling aphids in our guide.

Earwigs

European earwigs (Forficula auricularia) can’t pass up a peachy meal. They will chomp their way through the leaves of the tree at night.

Once the peaches start to ripen, they’ll start devouring the fruits in addition to the foliage.

When they tunnel into the fruits they leave soft pits behind, plus their excrement. No one wants to eat that peach anymore.

Any insecticide that contains spinosad will kill earwigs. Don’t have some in your gardening arsenal already?

Grab a hose-end quart bottle or a gallon of Monterey Garden Insect Spray at Arbico Organics.

Japanese Beetles

For many gardeners, Japanese beetles (Popillia japonica) are just a part of summer, like barbecuing or sitting poolside.

These beetles eat the leaves of the plant and they’re pretty easy to identify.

If you spot the metallic, half-inch-long insects, you might just opt to ignore them. But that’s not always possible, especially if the infestation is bad.

If you can’t stand it, read our guide to managing Japanese beetle infestations to learn more.

Peach Tree Borers

Peach tree borers (Synanthedon exitiosa and S. pictipes) suck. Like, suck with a capital S-U-C-K.

They’re the most destructive pests of peaches and other stone fruits and they can be a nightmare to control. The adults look like wasps, but it’s the larvae that cause all the trouble.

The larvae eat the wood of the lower part of the tree and the roots during the spring, leaving behind extensive damage.

This damage leaves the tree susceptible to disease and also weakens the tree, sometimes dramatically.

As with many problems, prevention is best.

While I generally avoid using broad-spectrum insecticides, this is one time you may need to break out the big guns.

You need to use a product that contains permethrin, a synthetic pyrethroid insecticide, such as Bayer Permectrin II, which you can find at Amazon in 32-ounce bottles.

Spray the tree in late June or early July and again two weeks later. This will kill any adults before they can lay the eggs that will emerge as larvae the following spring.

Peach Twig Borers

Peach twig borers (Anarsia lineatella) are the larvae of moths that feed on leaves, blossoms, and young shoots. The second generation will feed on the fruits, entering at the stem end.

The half-inch-long worms start out white with a black head and transition to dark brown as they mature.

Apply a product that contains spinosad, such as Monterey Garden Insect Spray, which we discuss above, or a product that contains Bacillus thuringiensis v. kurstaki.

Whichever you choose, timing is crucial.

Spray the tree when the blossoms are present and again when the fruits are just beginning to ripen.

Bonus! If you spray with Btk during bloom time, you can also reduce the likelihood of brown rot.

Learn more about peach twig borers in our guide.

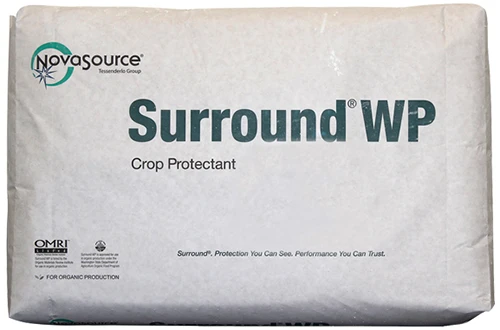

Plum Curculio

Plum curculios (Conotrachelus nenuphar) are ugly brown snout beetles that can be extremely destructive in orchards.

The quarter-inch-long beetle feeds on the young fruits of stone fruit trees, causing catfacing.

The females lay their eggs in the fruit, and the resulting larvae burrow into the flesh. This causes scarring, rotting, and early fruit drop.

To control this pest, spray plants with kaolin clay right after the petals fall and during the shuck-split phase of growth.

This is when the papery covering on the young, developing peaches starts to split open. Spray one more time two weeks later.

Kaolin clay-based Surround WP is available at Arbico Organics in 25-pound bags. As a bonus, it also helps to prevent some fungal diseases.

Scale

White peach scale (Pseudaulacaspis pentagona) and San Jose scale (Quadraspidiotus perniciosus) are common and pernicious pests of peaches.

Both of these small sapsuckers feed on the sap of the trees, and while they might be small, they can do a lot of damage.

Most people don’t realize they’re dealing with scale unless they’ve experienced the problem before.

That’s because the tree will look kind of stunted, wilty, or sad, but when you look close, you don’t see what you think are insects. You see little lumps on the bark that don’t move.

Dormant oil applied in the winter is highly effective at suppressing populations.

Don’t use indiscriminate pesticides because these pests tend to multiply out of control in gardens that lack natural predators.

Bonide All Seasons Horticultural Oil

Pick up a gallon-size Bonide All Seasons Horticultural and Dormant Spray Oil concentrate at Arbico Organics and follow the manufacturer’s directions closely.

Tent Caterpillars

Tent caterpillars look terrifying, with their wiggly masses of webby nests. But beyond some defoliation, they don’t do much damage.

They also tend to disappear for years at a time and then make a brief comeback.

We have a guide explaining why a broom and some patience are your best bets for dealing with these caterpillars.

Disease

Fungal problems are unfortunately common with peaches, and the best treatment is prevention.

Be sure to remove all fruit at the end of the season (if the squirrels don’t do it for you). Clean up fallen fruit, leaves, and other potentially fungus-harboring materials from the ground around the tree.

In addition to the following issues, watch for crown gall and rhizopus rot.

Bacterial Canker

The bacteria Pseudomonas syringae causes oozing cankers to form at injury sites or leaf or flower buds.

These cankers release a honey-like gum and can strangle the branch, causing it to die beyond the canker. Inside, underneath the bark, the tree turns sour-smelling and rotten.

The disease favors high humidity or rainy weather and moderate temperatures of 55 to 75°F, which means spring is its favorite time of year. It also prefers trees that are already weakened, and can spread on garden tools.

Since there’s no known cure, the main method of control is to prune off dead areas and do your best to keep your tree healthy.

To avoid bacterial canker, prune trees to improve air circulation and plant them an appropriate distance apart.

Clean your tools before using them near your trees and clean up any debris around your plants in the fall.

Bacterial Spot

There are several diseases that can cause spots to form on the leaves and fruits, but bacterial spot stands out because it causes angular gray spots on the underside of the leaves.

These appear water-soaked and eventually turn purple before rotting. On fruits, these can ooze a brown gum.

Caused by the bacteria Xanthomonas campestris, it needs moisture to breed and spread, so it’s rare to see bacterial spot during dry summers. Moist springs, however, are its heyday.

Brown Rot

Brown rot is extremely common and damaging. It’s caused by the fungus Monilinia fructicola and results in gray spores that rot the fruit.

Before that happens, the blossoms on the tree might turn mushy and brown, and twigs may develop cankers marked with brown spores.

The affected fruit might become mummified, and those fruits which harbor the fungus enable the disease to spread the following year.

All mummified and fallen fruits should be removed and disposed of.

Any insect that feeds on the fruit, leaves, or wood causes damage that leaves the plant exposed to the fungal pathogens that cause this infection.

Fungal Gummosis

Gummosis is one of those diseases that is hard to mistake for anything else.

When the fungi that cause it (Leucostoma persoonii and L. cincta) are around, the tree will exhibit oozing gummy areas on the wood. These fungi look for wounds or damage through which to enter.

Any sort of injury, from pruning to insect damage, invites this disease in, and treatment is sadly difficult. Gummosis tends to be more prevalent in warmer locations and no cultivar is immune to Leucostoma fungi.

We have a guide to help you learn how to prevent or treat gummosis.

Note that fungal gummosis is caused by a fungal pathogen, but you might hear people refer to gummosis as any sort of gummy-like sap oozing from a tree.

In this case, we simply mean that an injury has allowed the pathogen to enter the tree and caused the oozing symptom.

Leaf Curl

Leaf curl is a fungal disease caused by Taphrina deformans. As the name suggests, it causes the leaves to wrinkle and curl up.

Those leaves might also develop yellow, orange, or red patches, and the wrinkled, puckered areas might also form a white coating.

The affected leaves may turn brown and die or they may fall off the tree.

Copper fungicide should be sprayed on the tree every year just after the leaves have dropped to help prevent the fungus from attacking again in the following year.

Phony Peach Disease

A healthy-looking tree that suddenly stops producing fruit might be infected by the bacteria Xylella fastidiosa subsp. multiplex, which causes phony peach disease (PPD).

Once infected, there is no known cure, but prevention is possible. Learn about this disease in our guide.

Powdery Mildew

Powdery mildew is caused by the pathogens Podosphaera leucotricha and Sphaerotheca pannosa, which are fungi that attack plants in the Rosaceae family.

It causes a white or gray powdery growth on leaf and flower buds, followed by misshapen fruits.

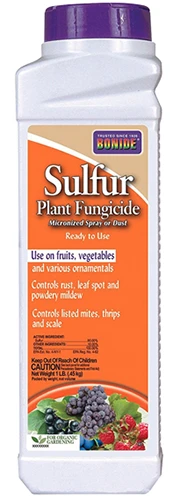

Grab yourself a sulfur fungicide and spray your trees at the first sign that this disease is present.

Sulfur prevents the spores from developing and spreading, but it isn’t highly effective in eliminating existing spores, so the sooner you treat, the better.

Keep some on hand in case the disease rears its ugly head. Arbico Organics carries one-pound and four-pound quantities or sulfur plant fungicide.

Repeat treatment once every three weeks until midsummer.

Scab

Peach scab, caused by the fungus Cladosporium carpophilum, is a common disease in all stone fruits.

Young fruits will start to exhibit green spots, which enlarge and turn brown as the fruit matures.

Sometimes you can just peel and eat the inside of the fruit, but other times the fruit will crack open and rot.

We have a whole guide to scab to help you learn how to identify and address this fungal issue.

Harvesting

It’s picking time! Peaches are ready to harvest when:

- They’re soft

- There’s no more green color on the fruit

- They come off easily with a slight twist

You can’t always go by color unless you’re familiar with the mature color of the cultivar you’re growing. Some peaches are almost white when mature and others need to be deep orange-red.

The fruits at the top and around the outside of the tree usually ripen first.

Be careful as you remove the fruit, as it bruises easily. If you do bruise a fruit, process or eat it right away because it won’t keep.

Pro tip: if you’re picking peaches and you can’t resist taking a bite, just loudly announce that “this one is bruised” and you can’t get in trouble for sampling the goods before the job is done.

You’re doing your part to prevent a bruised fruit from rotting and ruining any nearby fruits, and you deserve to be rewarded with a juicy mouthful.

You also can’t rely on the cultivar-specific recommended timing to tell you when to harvest. Nursery tags will often tell you that a certain cultivar should be ready by mid-August, for instance.

Peaches may be ready any time from late April (such as ‘Flordaking’) to late September (‘Jefferson’), but the timing will differ depending on your region and this year’s weather as well as the cultivar you choose.

When in doubt, take a bite of one.

And don’t worry if the fruit doesn’t fully ripen on the tree. Peaches are climacteric fruits, which means that the fruit itself produces ethylene, which aids in ripening.

This process continues even after you remove the fruit from the tree. So, if you happen to pluck a fruit that is a little underripe, just give it some time. It will soften up.

Of course, that also means the fruit will continue to soften past the point of peak ripeness, and you’ll be left with a soggy mess if you don’t use them in time.

But if you’ve ever eaten your average grocery store peach, which is typically harvested when immature, you know they never achieve the soft, sweetness of fruits allowed to mature on the tree.

Preserving Peach Fruit

Don’t put those fresh peaches in the fridge!

I mean, it’s your life, and you can do what you want, but peaches turn mealy when you subject them to lower temperatures. Instead, store them in a cool, dark area for a few days at most.

You can also wash and slice the fruits and dry them in a dehydrator, or turn them into fruit leather.

Peach jam is a piece of summer that you can eat during the dreary winter days. Whip some up using this recipe from our sister site, Foodal.

Recipes and Cooking Ideas

Everyone knows how incredible peaches are fresh off the tree or baked into pies, cobblers, and cakes. As a topping or ingredient in ice cream, they’re pretty hard to replicate.

But don’t let the peach love end there. These incredible fruits can be used in savory recipes as well. Use them to top meat, fill empanadas, or in a savory salad.

Ever had peach slices on pizza? Make it happen! This spinach and goat cheese pizza with a kefir and spelt crust from Foodal makes my mouth water just thinking about it.

Or make a quick snack with sweet peaches, creamy ricotta, and spicy basil on flatbread, also from Foodal.

To bring peaches to the summer dinner table, check out Foodal’s chipotle peach topping for chicken.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Deciduous stone fruit tree | Flower/Foliage Color: | Orange, pink, red, violet/green |

| Native to: | China | Maintenance: | Moderate |

| Hardiness (USDA Zones): | 4-9 | Tolerance: | Some drought, heat |

| Bloom Time/Season: | Spring, summer, fall | Soil Type: | Loamy to sand |

| Exposure: | Full sun | Soil pH: | 6.5-7.0 |

| Time to Maturity: | 4 years | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Spacing: | 18 feet (standard), 10 feet (dwarf) | Attracts: | Pollinators, birds |

| Planting Depth: | Same as growing container (transplants) | Companion Planting: | Marigold, red clover, strawberry |

| Height: | 25 feet | Avoid Planting With: | Nightshades |

| Spread: | 20 feet | Order: | Rosales |

| Growth Rate: | Fast | Family: | Rosaceae |

| Water Needs: | Moderate | Genus: | Prunus |

| Common Pests and Diseases: | Birds, rats, squirrels; aphids, earwigs, Japanese beetles, peach tree borers, peach twig borer, plum curculios, scale; bacterial canker, bacterial spot, brown rot, gummosis, leaf curl, phony peach disease, scab | Species: | Persica |

Everything’s Just Peachy!

Truly, the trickiest part of growing this plant is choosing the right cultivar.

Get some help from local experts to select the perfect type for your area, and you’ll be well ahead of the game.

From there, it’s all about feeding, watering, and watching for any signs of pests or disease.

What kind of peach is your favorite? Which are you growing? Fill us in on the details in the comments. And if you need additional help, send us your questions!

We hope this guide pointed you down the right path toward success with peaches. If you want to expand your fruit-growing knowledge even more, check out these guides next:

I have always wanted to have a fruit bearing tree and now that we have a big enough space I would love to plant a peach tree! Plus all the dishes you shared sound amazing!

You have written in your article that it is a spring season suitable for planting. But after reading your article I am curious to plant peach trees. Can I not put the grafted tree in this season, or will I have to wait until the spring season?

Hi, I live in Southern NM, we have a semi-dwarf Elberta peach tree. I harvested most all the peaches a few days ago. I noticed the tree still has what looks like a second harvested of small green peaches the size of ping pong balls. Will they continue to grow and ripen?

Thanks for your question, Judy! First, a few questions for you: How old is your tree? Do you thin your peaches near the beginning of the season, and prune your trees to promote good airflow and sun exposure? Are the remaining fruits growing on the same branches as the ones already harvested, or located on a certain part of the tree (i.e. peaches that ripened first were on exterior branches, unripe peaches on the exterior)? Is the remaining fruit falling off the tree, or showing any signs of rot, other types of physical damage, or insect damage? Thinning to provide… Read more »

Thank you for all the great information! As a kid who grew up in Corpus Christi Texas, my mom had 5-7 peach trees in our back yard! Each were wonderfully fruitful! Now I’m living in Leesville LA, and so excited to grow my own and share the experience with my children! Thank you again for all the helpful information!

This year I had flowers in early spring, saw bees on flowers and never had any fruit. Tree is at least 3-4 years old and each previous yr. has had increased fruit. Didn’t see and bugs or mold on leaves. Read all of this site, a word I don’t know is cultivar, can someone tell me what it means please??

Thanks for your message, Susan. A cultivar is a plant variety that has been produced by selective breeding, either a hybrid passed down through the generations or a hybrid of two or more types. Prunus persica is the peach’s botanical name, with the first word being the genus it belongs to, and the second being the species. Words to follow this name, often in single quotes, indicate the cultivar (P. persica ‘Galaxy’ or ‘Honey Blaze,’ for example). Sorry to hear you didn’t have any fruit this year. Many types of peaches are self-fruitful, and seeing bees in the area is… Read more »

What zone is Maryland in?

Hi Johnny, it depends where in Maryland, check out our guide to USDA Hardiness Zones for more information.