We all know what makes lilacs fabulous – it’s those spring days when you’re walking outside and you suddenly get a whiff of a heavily floral fragrance.

That’s when you look around and, yep, your lilacs are in bloom. Is there anything that smells as delightful as fresh lilacs?

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

Another reason people love lilacs so much is that they are mostly maintenance-free and known for being resistant to pests and diseases.

If you give them a hard refresh prune every so often, they’ll look lovely and bloom fantastically for years.

Unless, that is, one of the seven common lilac diseases comes calling.

While these plants are rarely troubled by problems, when they are, lilacs can have a hard time. Many of the following diseases will kill your shrub outright, and they don’t have a cure.

If you grow your shrub in the right location and provide adequate water and food, as discussed in our guide to growing lilacs, it will go a long way toward keeping your plant healthy.

But even if you do everything right, problems can occur. Here are the seven diseases we’ll discuss:

7 Common Lilac Diseases

Common lilacs (Syringa vulgaris) are generally more susceptible to problems than other species.

But breeders have been working hard to create disease-resistant options, so if you’re feeling down about diseases, look for those. We’ll call out some of these in the following guide.

1. Ascochyta Blight

Caused by the fungus Ascochyta syringae, this blight isn’t the most common disease of lilacs. But when it strikes, it has an outsized impact.

As new shoots and flowers emerge in the spring, they’ll quickly turn brown and wilt. Or, they might be girdled and die off. All that fresh new growth you were so excited about? Suddenly, it’s gone.

Other diseases can cause tip blight, so look for gray fungal bumps that develop all over the dead parts. Older leaves will have tan spots with these fungal bumps on them.

The moment you see the dying branches, prune them off. Then, start treating right away with a fungicide.

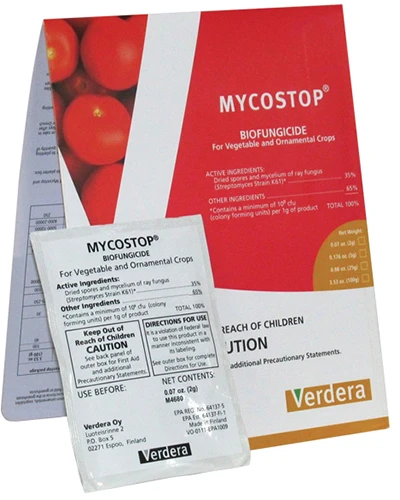

I’m a fan of Mycostop, which uses a beneficial bacterium found in sphagnum peat called Streptomyces strain K61. I can personally attest to its effectiveness against many fungal diseases.

Arbico Organics carries this product in five- or 25-gram quantities, and a little goes a long way.

2. Bacterial Blight

The bacteria Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae is super common and lives in just about every part of the world.

If you want to avoid it, you’ll need to move to Antarctica. In lilacs, the pathogen causes what we call lilac bacterial blight.

All that’s nice to know, but what does it mean for your plant? When it infects the plant, it causes brown, water-soaked lesions to form on the leaves.

The spots start out as teeny little pin-sized spots, but they’ll keep growing until they merge with each other and create large necrotic areas.

As that takes place, the leaves start wrinkling and curling, and they might drop off the bush.

In the spring, when the shrub is sending out new, tender growth, it will turn brown and rot. When the lesions form on the stems and branches, it can cause girdling and death.

New buds will turn brown and drop from the plant.

The bacteria overwinters in fallen debris, within the plant itself, or in nearby weeds. It can live on the most minute piece of material in the soil. What I’m trying to say is that it’s really hard to avoid.

On top of that, it’s spread by water, wind, pests, and garden tools. Given cool, wet weather, it starts to spread like wildfire. But don’t lose hope – it has a weakness.

The pathogen needs to have an opening to get into the plant. It’s easier said than done, but if you avoid damaging your lilacs and you’re able to keep pests away from your plants, it will go a long way toward keeping this disease away.

Minimizing splashing and always cleaning your garden tools with soap and water before and after use adds another layer of preventative protection.

Obviously, you can’t avoid pruning altogether. But if you use clean tools and prune only when the weather is dry and calm, and when it’s expected to stay that way for the next few days, this will limit the chances that the pathogen will infect the wounds.

Keeping your plant healthy with appropriate watering and feeding helps lilacs to withstand infection, and if yours does contract the disease, this can help it survive.

Appropriate spacing and pruning for airflow are also important.

If you’re really concerned about this disease, be aware that white lilacs seem to be more susceptible.

Cultivars including ‘Annabel,’ ‘Burgundy Queen,’ ‘California Rose,’ ‘Charm,’ ‘Edward Gardner,’ ‘Etna,’ ‘Little Boy Blue,’ ‘Monge,’ ‘Olimpiada,’ and ‘Yankee Doodle’ seem to be particularly susceptible.

On the other hand, ‘Cheyenne,’ ‘Edith Cavelle,’ ‘General Sheridan,’ ‘Glory,’ ‘Katherine Havenmayer,’ ‘Montaigne,’ ‘President Grevy,’ ‘Pink Elizabeth,’ ‘Saugeana,’ and the S. josikaea, S. komarowii, S. microphylla, S. pekinensis, and S. reflexa species are resistant to some degree.

3. Fungal Leaf Spot

Fungal leaf spots are caused by fungi in the genus Pseudocercospora. The same fungi will attack all plants in the Syringa genus as well as guava, mulberry, and olive trees.

Japanese tree lilacs (S. reticulata) are particularly susceptible.

During the spring and summer when temperatures are around 75°F, especially with high humidity, affected leaves will develop these dark green or brown patches that stop at the veins, so they have a sort of angular appearance.

These leaves might eventually drop from the plant.

But regardless of whether they fall or not, the plant will be stunted and weakened because it isn’t photosynthesizing as well as it should, especially if a high percentage of the foliage is impacted.

The disease can also cause shoots to die back.

The first step if you note signs of fungal leaf spot is to remove any sick leaves, which might mean removing entire branches.

This is usually enough to control a minor infection, but if your plant is seriously infected, with a majority of the leaves showing symptoms and severely restricted flowering or growth, you’re going to need to pull out the fungicides.

Clean up any debris in the fall, because the fungi can live on plant debris for at least two years.

If you opt to go for a fungicide, use something that won’t upset the delicate environmental balance in your garden. There are some excellent biofungicides out there that provide targeted control with less of an impact.

Streptomyces lydicus is a bacterium that is effective against a broad range of bad fungi and bacteria that lives on foliage.

Something like Actinovate SP, which is available at Arbico Organics in 18-ounce bags, contains this bacterium and can be mixed with water to apply to the foliage.

Spray your shrub and the soil around it once every two weeks while the symptoms are present.

The following year, apply it again two times in the spring, just after the leaves have emerged and opened.

This is a preventative step that will kill off any pathogens that managed to survive through the winter.

4. Powdery Mildew

Powdery mildew is a fungal disease that causes an easy-to-identify, white, powdery growth. You’ll often see this growth on plants or leaves that are in shaded conditions.

The mildew usually starts on the lower part of the plant and works its way up. It can also cause the leaves to discolor.

It usually starts in late spring as the temperatures increase, especially in high humidity.

Don’t panic if your lilacs contract this disease. While it’s not ideal, it won’t kill your plant. It’s just kind of ugly and, in extreme cases, can reduce the vigor of your plant.

Caused by the fungus Erysiphe syringae (syn. Microsphaera syringae), rather than treating it with harsh chemicals, a little bit of gardening hygiene can go a long way.

Regular pruning to open up the plant and improve air circulation, as well as proper spacing when planting, can be helpful. Ensuring your plants are growing in full sun is also a good preventative.

In general, S. vulgaris and all cultivars are susceptible, while other species tend to be more resistant. Of the vulgaris cultivars, ‘Charles Joy,’ ‘Old Glory,’ and ‘Sensation’ are more resistant.

If you’re really worried about your plant and you want to learn more about some powdery mildew control methods, read our guide to this oh-so-common disease.

5. Shoot Blight

Shoot blight is a disease caused by the oomycete Phytophthora cactorum. An oomycete is a microorganism that is often confused for fungi, but it’s more closely related to algae.

One of the worst things about this particular disease is that it appears as just a general malaise, with wilty, browning, curling leaves. Below ground, the young roots are dying off, causing the plant to struggle.

It’s hard to pinpoint the disease based on these early symptoms. Eventually, the young shoots will start to die, at which point, you might start realizing that your lilac is in trouble.

The other challenge is that there isn’t a known cure, and once it’s in your soil, it can live there for up to a decade.

You can support your plant by keeping it well watered and fed, and also pruning off the dead ends. Once the disease progresses and the plant starts dying, you’ll need to just pull it. Don’t plant lilacs there again for 10 years.

Dogwoods and forsythia are also hosts, so don’t plant them either. Instead, substitute ninebark (Physocarpus spp.), spirea (Spiraea spp.), or sumac (Rhus spp.).

6. Witches’ Broom

In some species, witches’ brooms can cause some fun growths that can be used to propagate exciting new plants. But in lilacs, it mostly just makes them ugly.

Witches’ broom causes new branches to die, or it can create abnormal growth like a bunch of tangled, weak shoots, and distorted or yellow leaves. Leaf edges might also turn brown, and new leaves might be small and pale.

Eventually, this growth will spread, and the plant will die. See? It’s no fun at all.

This strange growth is caused by the bacteria-like ash yellows phytoplasma (Candidatus Phytoplasma fraxini). This pathogen can also infect ash trees (Fraxinus spp.).

Once your plant is infected, there’s nothing you can do. It’s going to eventually die. Rather than wait for it, pull your lilac to avoid allowing the pathogen to travel to other plants.

Be sure to toss the diseased material in the garbage, not into your compost. Don’t shred it to use as mulch.

Since the disease is spread by leafhoppers, doing your best to control these pests can help keep it from visiting in the first place.

7. Verticillium Wilt

Many woody ornamentals are susceptible to verticillium wilt, sometimes called vert for short. Lilacs are particularly susceptible to the fungus that causes this disease, V. dahliae.

As with several other diseases on this list, the first symptom is wilting branch tips. Sometimes entire branches will start wilting. How do you tell if it’s vert or another disease?

Peel away the bark on the wilting branch. Do you see streaks of brown or green? You can be certain that’s what you’re dealing with.

However, you shouldn’t assume a lack of streaks means it’s not wilt because lilacs won’t always show this symptom.

Look for small, yellow leaves or a pattern of dead branches on just half of the shrub to help you to be certain.

So, now that you’re sure you’re dealing with vert, what can you do? Not much, unfortunately.

You can prune off the wilted branches and hope for the best, but your plant will eventually die. At that point, rip it out and dispose of it.

Since the fungus is soil-borne, it’s already in your garden, so there isn’t much use in tearing out plants that are only mildly symptomatic.

Don’t Let Lilac Diseases Get You Down

I sincerely hope you’ll never have to deal with any of these issues. But if you do, know that it happens to all of us, and there’s always something new and fun to grow.

That might be a more resistant cultivar or a different species altogether, but that’s the challenge of gardening, right?

What kind of lilac are you growing, and what problem are you dealing with? Are you looking for help? Let us know what’s going on in the comments.

Now that you’ve sorted out your disease woes, there’s more you might want to know about lovely lilacs. Here are a few guides worth checking out if you’re looking for more:

Please help me identify what’s wrong with my lilacs and what I can do to help them 😭😭😭

See images here

I’m sorry you’re having trouble! That looks like fungal leaf spot, which we discuss above. The leaf spots and the curling of the leaves are all common signs. Controlling this with a spray will need to start first thing in the spring. For now, be sure to clean up any fallen leaves and keep the area around the plants clean.

Can you help me identify what I’m dealing with on my giant old lilac?

Hi Steph, unfortunately, this looks like bacterial blight. Prune off the infected areas and do your best to support the health of the plant with appropriate watering and feeding. Next spring, start spraying with copper the second the leaf buds start to swell and spray every two weeks until the plant stops flowering. Be aware the the bacteria that causes this disease, Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae, can infect lots of other plants. Blueberry, cherry, maple, and pear are all susceptible. I could be wrong, so before you decide to pull the plant, you might want to have the disease confirmed… Read more »

Please help me identify what is happening to my 14 year old Japanese Lilac tree. I don’t want to lose it. I have confirmed it is not overwatered and it is not iron deficiency. Thank you.

Hi Nancy, with this kind of interveinal chlorosis (which just means yellowing between the veins), it’s usually some sort of nutrient deficiency. Since it isn’t iron, it could be a lack of manganese, molybdenum, or magnesium, with magnesium being the next most common after iron. Have you done a soil test? If you have and everything checks out, do you have an excess of anything? As odd as it sounds, an excess can cause a deficiency in other nutrients. Also, is there enough water in the soil for the plant to take up nutrients? Is the pH balance of the… Read more »

Can you identify what’s wrong with my lilac bush and recommend a remedy? Thanks!!