Starting a worm farm is an ideal way to reduce the amount of household food waste and create nutritious, organic compost for your plants and garden. And it’s fun, easy, and economical too!

You don’t need a lot of space either because you can set up a kit to fit on a balcony or in a courtyard space, so it’s beneficial for urbanites as well as rural dwellers.

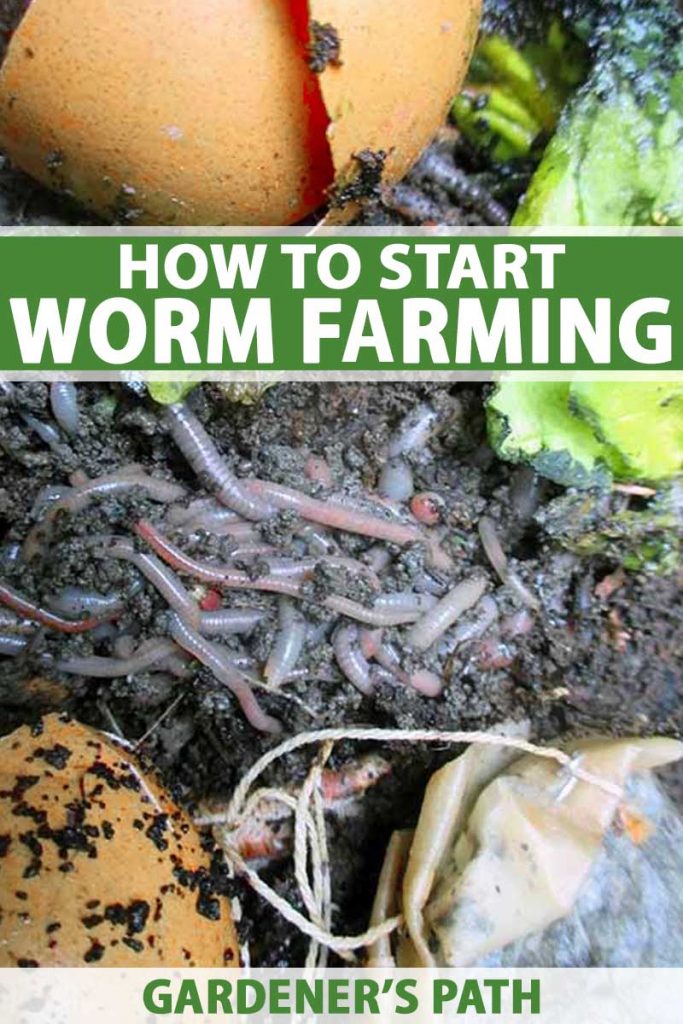

The compost is created by hungry and hardworking worms as they eat their way through food scraps and other natural materials.

The result is a nutrient-dense byproduct known as castings or vermicompost – vermi comes from the Latin word for worms, vermis.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

Setting up your own worm farm is easy, and it requires little maintenance, save for adding food scraps to feed the hungry worms. After working for a few months, the little wrigglers will produce ample amounts of ready-to-use castings.

Plus, they reproduce readily, so they’re constantly providing a new generation of compost builders!

And with just a little bit of maintenance, vermiculture is an odor-free system with no stinky smells to deal with.

So if you’re ready to reap the benefits of turning kitchen trash into dark, nutrient-rich soil, let’s dig into how to start a worm farm for rich vermicompost!

Here’s the outline for what’s ahead:

What You’ll Learn

Benefits of Vermicompost

With a properly designed system, vermicasting successfully processes kitchen waste into fertile compost.

There are numerous benefits to starting your own worm farm:

- Vermicompost is clean with little or no odor.

- The soil doesn’t require turning as the tunneling wrigglers provide aeration.

- Castings are produced within a few weeks without having to maintain internal heat.

- Recycles and repurposes kitchen waste materials .

- Produces nutrient dense, porous compost with good water retention and high microbial activity.

- The castings produced are easy to apply, handle, and store.

- Generates a steady supply of fishing bait.

Vermicompost plays a role in improving the soil’s ability to hold water, which helps to move nutrients to plants, improves soil structure, and neutralizes soil pH.

Compared to garden compost, it provides greater amounts of bioavailable macro- and micronutrients, including the all-important trio of NPK – nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium – plus calcium, magnesium, and other trace elements.

It also contains a rich microbial community that helps to promote plant growth, including the presence of beneficial bacteria that make phosphorus more bioavailable to plants, fix nitrogen in the soil, and produce growth hormones.

Vermicompost is also pathogen-free and helps to protect plants by inhibiting or repelling soilborne pathogens while helping to increase biological resistance against pests and disease.

It also works as a soil conditioner and has excellent moisture retentive properties, with a moisture content of 32 to 66 percent and a neutral pH of 7.0.

Setting Up Your Worm Farm

To set up your own worm farm, bins can be made of a wide variety of clean materials including galvanized iron, plastic, stainless steel, or wood.

The bottom and sides need to be perforated to allow for aeration and drainage, and your system needs a removable top to facilitate feeding that can be closed tight to protect your worms, which are sensitive to daylight.

Don’t worry about the perforations being big enough for your little guys to escape. If you’re doing things right, they won’t want to leave their box!

Bins also need to be deep enough to hold bedding materials, castings, and food scraps.

The size is up to you, but a 10-gallon capacity is a good starting point.

If you plan to build from wood, untreated lumber must be used – you don’t want to poison your worms with toxic preservatives leaching into their beds.

Also, all wooden bins need to have the bottom and sides lined with plastic. Wood absorbs moisture readily, which can lead to unpleasant odors.

In addition to your main worm bin, you’ll need a waterproof tray to catch and collect drainage fluids. The ideal catchment tray should be an inch or two deep and about two inches wider than the dimensions of the bin.

Lids intended for plastic storage bins can be used as catchment trays or an indoor/outdoor shoe and boot tray is a good choice too.

For big buckets or storage bin setups, instead of using a catchment tray, you can stack the perforated bin or bucket into a second unit to catch the drippings.

With the right setup, you can expect to see usable amounts of vermicompost in six to eight weeks.

Prefab Bin Systems

If you’re not interested in crafting your own bin system, there are plenty of prefabricated containers available that are designed specifically for the job.

The Worm Factory 360 Worm Composter is a multi-tier mini factory that’s easy to assemble and manage. It consists of four stackable trays and is 17.95 inches long and wide, and 14.95 inches tall.

Made in the US of durable plastic, it provides odor-free operation and sits on a sturdy catchment base with a spigot for draining liquids.

The Hot Frog Essential Living Composter consists of three trays of BPA-free polyethylene with double wall insulation that gives good interior temperature control. Its dimensions are 15 inches long and wide by 22 inches tall.

Hot Frog Essential Living Composter

A robust drainage base sits on four strong legs and has a spigot to siphon off drainage liquid. The Living Composter can be purchased at Arbico Organics.

Lightweight, and with a compact size of 15 inches square and 14.5 inches high, ideal for the kitchen, the Wow Worm Farm Composter is made of recycled polyethylene.

It consists of two bins and sits on a durable catchment base with a drainage port to remove liquids. Available at Gardeners Supply.

Once your homemade or prefab farm is set up, the next step is to create a welcoming environment for your worms.

Preparation

When you’re ready to house your worms, following a few basic preparation steps will make sure your little guys are comfortable and will help to support them in becoming compost-making machines!

Here’s how to prepare your containers before adding your worms:

1. First, line the bottom of your container about one-third deep with fluffy and slightly moist carbon materials – this is the bedding for the worms.

Use carbon-rich materials like coconut coir, dried leaves, shredded paper or newspaper (but don’t use the glossy inserts), straw, or wood chips.

2. Next, add a layer of nutrient-rich soil.

Depending on the size of your bin, sprinkle two to four cups of garden soil or finished compost over top of the bedding material.

This introduces beneficial bacteria and other important microbes that start to break down the bedding material into a nutrient-rich slurry, providing the worms with a quick meal when they’re first introduced.

Please note that sterile potting soil is devoid of beneficial bacteria and will not achieve the same results.

3. The third step is to spritz the bedding material and soil lightly with water.

The worms need a lightly moist environment, but don’t add too much water. The bedding and soil should be damp, but not wet.

4. About one week after adding the soil, release your stock into their new environment.

Use a soft touch to scoop them by hand onto the top of the material or simply open up their shipping container and gently turn it upside down onto the bedding.

Along with the setup and prep, determining the quantity of worms needed is an important step.

How Many Worms Do You Need?

The number of worms needed for an effective vermifarm depends on a number of factors, including bin size, moisture levels, pH, soil temperature, bedding materials, and the amount of available food.

An exact formula hasn’t yet been determined, but it’s helpful to come up with a guesstimate of how much waste you think you’ll produce in a week.

If you produce a lot of food scraps, a larger work force is needed than for situations with more moderate amounts of waste materials.

A rough guide is to provide one square foot of bin surface for one pound of waste per week. This ratio helps to prevent overfeeding and maintains key factors like air flow – like us, these tunneling invertebrates need oxygen to survive.

As a general rule of thumb, one pound or approximately 1,000 adult wrigglers per square foot is a good starting number.

Keep in mind though, the worms reproduce quickly when they’re happy and well-fed, so it’s better to start out with a more modest number than way too many.

If you’re new to the practice, a conservative number of 500 worms, or half a pound, is a safe starting point.

Worm Species to Select

Before you start digging up the backyard for a supply of wrigglers, you should know that not all species are suitable for producing castings.

There are three different types of earthworms who do their thing at different soil depths.

- Epigeic varieties, also known as leaf litter dwellers, reside on the surface of the soil.

- Endogeic species are called soil dwellers and they live in the top 20 inches of soil.

- Anecic varieties are deep burrowers that can tunnel to a depth of six feet but rise to the soil surface to eat.

Most backyard earthworms are typically soil dwellers, and they don’t consume large amounts of food waste or reproduce well in confined environments.

For the purpose of vermicompost, the preferred types are the surface dwellers, or epigeic species. They’re communal, feed on the surface of the soil, consume large amounts of food scraps, and reproduce abundantly in a confined space like a bin or container.

Among the most popular and easily obtained of epigeic varieties are red wigglers aka tiger worms, Eisenia fetida, and European nightcrawlers, Dendrobaena hortensis.

Redworms, Lumbricus rubellus, are also used for their castings but they reproduce slower than red wigglers and nightcrawlers and are classified as an invasive species in the US and Canada.

Red Wigglers

Red wigglers (Eisenia fetida) are the most popular and considered the best species for breaking down food scraps quickly and efficiently.

Although they’re relatively small, with a mature length of five inches, they’re the most active and can consume their body weight in waste material in a day.

However, they require a warm, humid environment and can’t be left in an unheated outbuilding during cold winters where the temperature drops below 40°F.

Red wigglers also reproduce much faster than other types, so you can start out with a small number and in just a few months, they’ll double in population.

Nature’s Dream Ranch has a live count container of 250 red wigglers available at Walmart.

European Nightcrawlers

European nightcrawlers (Dendrobaena hortensis), or super red worms, are another great option for home worm farms.

This species is larger than red wrigglers, growing up to eight inches long, but they aren’t quite as active and therefore don’t eat as much in proportion to their bodyweight.

They also reproduce more slowly than red wrigglers, but they are still much faster than many other varieties.

Nightcrawlers are able to withstand colder temperatures – down to 30°F – if they have deep bins to burrow into. This makes them ideal for those in cooler regions and who want to keep their farm in a cool outbuilding.

They are also used and sold as fish bait. In USDA Hardiness Zone 7 and above, they can be safely added to your garden and lawn for aeration and to assist in the breakdown of leaf matter and other organic materials.

Nightcrawlers from Speedy Worm in a 100-count container can be found at Walmart.

To purchase a greater volume, Arbico Organics has a 1000-count bag of a three-species combo for composting and gardening.

Location

Whether you set up your farm inside or outdoors, it needs a coolish, dry location that’s protected from the elements and extreme temperatures.

Outdoors, it needs somewhere that stays on the cool side during the heat of summer, such as in the shade from the north wall of a fence, garage, home, or shed.

When winter’s frigid temperatures come around, you can bring the setup inside, preferably somewhere that receives some warmth and natural sunlight during the day.

Or if your climate permits, a farm can be kept outdoors during the winter in a sheltered spot but needs to be switched around to face south, if you had it facing north during the summer.

It should also have a cover for protection from ice, snow, and other wintry precipitation, and receive a good amount of sun during the day.

For extra winter protection and to help retain heat, cozy up your farm by covering it with a black tarp to absorb sunlight.

Indoors, keep your farm away from fans, heaters, or heating vents that could damage your worms or dry out their home.

The ideal temperature range for producing castings is 55 to 80°F, and most farm wrigglers can tolerate temperatures down to 32°F.

However, temperatures above 80°F are too hot for them and below 32°F is too cold.

Use a soil thermometer to check the temperature in your worm farm regularly and aim to maintain conditions between 60 and 80°F for the most activity.

Keep feeding your vermicompost constantly, even throughout the winter – an active pile creates its own heat, which will help keep your worms warm.

Dietary Basics

The important aspect of their ability to produce castings is the dietary needs of your worms.

To produce rich castings, they need to be fed organic scraps that are degradable, edible, and safe for your wrigglers.

Acceptable foods and materials include the following:

- Bread, crackers, and non-dairy baked goods

- Coffee grounds

- Dried leaves

- Eggshells

- Fruit scraps (non-citrus)

- Grass clippings

- Hair (human and pet)

- Nuts and seeds

- Rice and pasta

- Soy products (tofu, tempeh, miso, etc.)

- Tea bags

- Untreated paper scraps

- Vegetable scraps

Also, it’s important to avoid feeding them certain items that can be harmful to the worms or that can become rancid and produce foul odors.

To keep your stock healthy and happy, avoid the following:

- Bones of any kind

- Cat litter

- Charcoal or wood ash

- Citrus fruits

- Cooking oils, animal fat, grease

- Dairy products (yogurt, milk, cheese)

- Diseased plants

- Eggs (eggshells are acceptable)

- Meat of any kind

- Pet feces

- Pickled foods/vinegar

- Plastics or any petrochemical products

- Seedy garden weeds

- Salty foods

- Sand

- Spicy foods such as garlic, hot peppers, onions

Along with a healthy diet, a few maintenance steps will help keep your worms happy and producing ample amounts of castings.

Care and Maintenance

Once your bin is set up and your worms are in their new home, you can add kitchen scraps, yard debris, and other suitable materials as they’re generated.

Simply toss what you’ve collected into your container on top of the lining and cover with a bit of carbon or brown materials such as dried leaves, shredded untreated paper, or untreated wood chips.

Adding a carbon layer on top of fresh food scraps helps to ensure decomposition happens in tandem with casting production, and also helps to keep odors at bay.

Harvesting Vermicompost

Finished vermicompost can be harvested in a few ways.

1. Every three to four months, stop feeding your stock for 10 to 14 days then rake the castings to one side.

Add fresh bedding materials to the raked side, then resume feeding, adding food scraps to the new bedding only.

Your wrigglers will migrate to the new bedding in a few months, after which you can collect the finished castings.

After harvesting, fill the empty side with fresh bedding and add food scraps.

2. Every few months you can dump the bin contents onto several layers of plastic sheeting in a brightly lit room – the light-sensitive invertebrates will dig themselves down to the bottom.

Harvest the top of the pile.

Add fresh bedding to the bin, place the remaining worm-bearing residue on top, then resume adding food scraps.

3. The final method is the easiest. Every few months, simply remove about two-thirds of the bin contents and apply it to the garden, giving some of your stock their freedom!

Add fresh bedding and food scraps and allow the worms to repopulate at their own pace.

Use the first two methods if you want to use the castings for houseplants, as the collected material will be mostly worm-free.

All three methods can be used in garden beds and outdoor containers.

Worm Reproduction Habits

One of the big perks of vermiculture is the ability of worms to reproduce quickly, which keeps populations thriving and healthy for consistent casting production – without the need to restock.

Once the wrigglers are two to three months old, they’re mature enough to start reproducing, which they’ll do on their own without any help from the farmer.

After they’ve mated, they’ll lay eggs and create a small cocoon for incubation. After a few weeks, baby worms emerge and get to work on creating your compost.

Theoretically, this means populations can double every few months!

But you don’t have to be concerned about overpopulation. In a confined farm environment, they tend to self-regulate population growth, balancing the number of inhabitants with the available space.

Amazing Compost

Worm castings make amazing, clean compost loaded with beneficial minerals and organisms that help plants to flourish in your home and garden.

And with relatively little effort, you can build your own vermifarm or use a prefab system to get started quickly.

All you need for a vermi-friendly environment is some bedding material, a sprinkle of soil, food scraps, and the right kind of worms.

And once you get your farm set up, you’ll love how quickly your food scraps and waste are turned into beautiful, dark compost, creating your own organic fertilizer right at home!

If you’d like to know more, check out “The Worm Book: The Complete Guide to Gardening and Composting with Worms,” available via Amazon.

Want to try vermicomposting or are you already making your own vermicompost? Tell us about it in the comments section below.

And for more information on improving the soil in your backyard, check out these guides next:

Wow. Good article for learning. Really worth sharing.

Question: I am trying to convert a sandy location into good soil. All summer I have been putting grass clippings and straw and tilling it in weekly. Would adding worms to the soil work? Would the straw and clippings provide nutrition for the worms? When the leaves start to fall I will be adding them to the soil.

Hi Bart, I’m sorry it has taken us so long to get back to you – somehow your message slipped under our radar. Bart, while I’m guessing you have sorted out your problem by now, for the interest of our other readers I will go ahead and answer your question here. To improve sandy soil, I would advise adding organic matter as you have been doing. Rather than introducing earthworms directly, I would work compost and / or manure into the soil. Once you have increased organic matter in your soil, soil critters like earthworms will find their way to… Read more »

If I want to keep the population about the same could I feed to chickens?

Great question, Bella. Red worms are high in protein, and they can definitely be fed to the chickens!

I’m very interested in becoming a worm farmer and at this point I’m ready to supply myself with whatever I can out of my own resourcefulness. Your information that I just read seems to be a quite a helpful resource and I hope to be learning much more in the coming days and weeks so that I can begin to become a worm farmer. Thank you!

Thank you very helpful,:)

I just started worm composting and I have a problem. I have had my worm bin for about 2 months and last week I checked my worms. I saw very few worms but there were bunches of a larva type thing. The largest was about 1 inch long and they were light and dark gray stripes. I picked as many as I could out and threw them away. Today when I fed them I saw the larva again and they were defiantly more populated in the bin than the worms. What worms were in there were tucked off in a… Read more »

I’ve had this issue before — there is a good article about these (probably maggots) on Gardening Know How.

I heard a similar story on a podcast recently, Dave, and unfortunately that gardener thought it would be a good idea to dump out the entire bin and hand-pick the grubs – in her apartment kitchen. I would advise against attempting this indoors! Unfortunately, soil and other garden materials can sometimes be infested with unwanted bugs that are just waiting to hatch, and there’s not much you can do to eradicate them that won’t also harm the worms. If these are maggots or potworms, they won’t technically harm a vermicompost bin. But finding them can be unpleasant, and worrisome. However,… Read more »

I’ve had a similar problem.

I found that putting a couple of cut summer squash the larvae seem to really like the squash and will cover it in about a day then take it out to the chickens and they will take care of it from there after a couple times you will thin them out pretty well

Thank you so much for the great research & experience you’ve shared! I am so

excited to start “Farming” nature’s true farmers. Giving tips on how to do it yourself and links to purchase is super appreciated!!! Thank you ????????

Are earthworms found in cow dung suitable for vermicomposting? I am on a tight budget so no online buying for me. ????

Hi Melinda, I’m sorry it has taken us so long to get back to you – somehow your message slipped under our radar. I would advise against using earthworms from cow dung for vermicomposting. Cow dung can contain other types of worms or insects that you would probably not want to introduce into your home, including parasitic worms. Also since it would be difficult to correctly identify the types of earthworms in the dung, you may not find the type that are suited to vermicomposting. For free earthworms, I would recommend looking for a local group of gardeners and see… Read more »

Hi I have 2 worm farms, the worm are fine and reproducing. The problem I have is my compost/casting is always very moist. Please help. Thank you.

Hi Linda, It’s great to hear your worms are reproducing successfully! First of all, the contents of your worm bin should be about as moist as a wrung out sponge. I can think of a few reasons why your castings might be more moist than you prefer. The first depends on how much water you’re introducing with your paper. When you get your newspaper wet, I would recommend wringing it out like a sponge before you put it in your worm bins. If that doesn’t seem to be the problem, perhaps your worm bins don’t have enough ventilation. If you… Read more »

Good article! I just started a worm bin, the purchased type with several trays. I keep the bin in my utility room because I live in an area with very hot summers and winters below freezing, and I didn’t think I would be able to move the bin inside and outside by myself. The worms seem happy, but I’m surprised that I often need to add water, and I’ve had no leachate to drain. I’ve read of so many problems with too much moisture. I check the moisture level each time I feed. I just added a second tray. My… Read more »

Hi Thisni, It sounds like you are a top notch worm farmer, congratulations! Thanks for providing so much info in your question – the details you provided may have helped me figure out the cause of your lower moisture situation. Frozen vegetable materials allowed to thaw tend to release a lot of moisture. My guess is that the water released from the veggie scraps is draining away through a colander or something, and so the scraps have less moisture content than fresh veggie scraps would. I could be wrong about this, but that would be my first guess. If that… Read more »