Lonicera japonica

What is the appeal of the honeysuckle vine? The nose knows.

In some parts of the world, it’s considered the definitive scent of summer. The fragrant blooms beckon to pollinators in the summer months, with the intoxicating, vanilla-like aroma drifting on the warm breeze.

The first experience I had with Japanese honeysuckle was on a warm spring afternoon in Maryland.

I had stumbled upon an abandoned farm while hiking, and observed a vine that had overtaken the entire length of a wooden perimeter fence.

It was heavy with white blooms, and buzzing with life as bees and other insects floated from stamen to stamen.

I recognized the blooms as honeysuckle, but I was unfamiliar with the nonnative type that grew as a vine. After researching a bit, I learned about this species, and how it came to be part of the Maryland landscape.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

This vine, also known as “gold-and-silver honeysuckle,” produces blooms from late spring through fall.

While it’s a cousin of the North American native honeysuckle, L. sempervirens, the Japanese variety was introduced to the continent and has naturalized in many areas, with the exception of the southwestern part of the US.

In many parts of the United States, in fact, the vine is classified as an invasive species. When given the chance, this plant can sprawl as a groundcover or a climbing vine, reaching lengths of more than thirty feet in ideal conditions.

So, where and how can you plant it without risking negative environmental impact? Let’s talk about that – and how to keep the olfactory delight going strong, all summer long!

What You’ll Learn

Cultivation and History

There are approximately one hundred eighty species of honeysuckle, or Lonicera, and several of these are native to North America.

Flowers can range in color from bright white to pink or red. Leaves are waxy and, in areas with mild winter conditions, remain evergreen.

Japanese honeysuckle, however, is native to eastern continental Asia and Japan. In traditional Chinese medicine, parts of the plant have been used for centuries to treat various health conditions, such as fever and dehydration.

Compounds found in the white flowers and red-hued stems have also been found to have antifungal and antiviral benefits, as evidenced in Western medicine.

The blossoms have also been used to make tea for centuries throughout Asia, and more recently, in other places such as the United States.

In the early 1800s, vines of this species were introduced to North America from Asia.

At the time, crews tasked with maintaining public roadways in several states planted the perennial vines with the intention of reinforcing embankments and creating drainage barriers adjacent to developing roadways.

Because it forms a dense groundcover, it was used to prevent weeds and other plants from growing in areas that needed frequent maintenance, such as along roadsides.

It was also planted in state parks and other wilderness areas as a source of winter forage for deer and other wildlife, and summer forage for pollinators.

At the time, some state environmental agencies viewed the plant as a positive introduction to the environment as it served many purposes.

What’s the saying – the worst mistakes are sometimes borne of the best intentions?

That’s unfortunately true in this case as the vines spread quickly beyond control, sending out runners and forming rhizomes, or bulbous roots, in the ground, and sprouting from seed.

In the fall, the fragrant, pollinated blooms develop into deep blue-black berries that resemble blueberries.

Various types of wildlife readily consume the berries, though toxic to humans and pets, and they can transfer the seed miles away from the original forage source through their droppings.

In ideal conditions, the stems of this vine can reach more than thirty feet in length, and it’s known to aggressively climb adjacent structures and plants.

The Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants at the University of Florida classifies this vine, and other plants, as invasive because of their “fast growth rate and ability to displace native species.”

It’s been found in more than half of the states within the continental United States, and Hawaii, and is considered an invasive plant in most states between the east and west coast.

Some states have enacted laws banning it altogether.

An invasive plant impacts the environment by competing against the native species for space, water, and nutrients, and in the case of this vine, it can grow so densely that it smothers out all other plants across quite a large area.

It can even prevent the growth of tree saplings by creating a light-depriving canopy. Saplings growing nearby can be strangled out when the vine causes girdling, or tight wrapping around the trunk.

The vine also produces compounds in the soil that can inhibit the growth of other plants in close proximity.

Flowers of the Japanese honeysuckle, and other honeysuckle vines, are considered something of a summer delicacy – hence the name.

Gardeners, hikers, and others who’ve learned that the nectar of the blooms is sweet and tasty can be found sampling from the white to yellow, trumpet shaped flowers. It’s important to note that only the blossoms and nectar are edible, and all other parts of the plant are mildly toxic.

This deciduous vine grows best in USDA Hardiness Zones 4 to 9, with scattered occurrences even further north and south. It can be found growing in full sun to full shade settings, although it grows fastest when exposed to full sun.

While it’s a lovely addition to the summer landscape, it should be planted with a note of caution.

Once control is lost, the vine will spread vigorously, both above and below ground. If it’s allowed to cross the line into invasiveness, you’ll have quite the fight on your hands to eradicate it.

Rhizomes can be found spread out in the ground much further than the sprouted vines may indicate, and will need to be dug out by hand, as any left in the ground will continue to grow and spread.

Any berries that escape with wildlife or through environmental factors, such as wind and rain water runoff, will find a place to sprout and grow unchecked.

If you’re considering planting Japanese honeysuckle, be prepared to keep a close watch on it so you don’t contribute to potential environmental destruction. You might consider planting a native species instead.

But, if you’re prepared for the commitment of keeping it contained, let’s talk about how propagation can be achieved.

Propagation

It’s exceedingly easy to plant and grow Japanese honeysuckle. So easy, in fact, that you may find yourself dealing with an unplanned overabundance of the vine.

Bear in mind, when planting a potentially invasive species, that neglecting to prevent the spread of the plant can negatively impact the environment in your area, and it is up to gardeners to heed local regulations.

Consider planting in a container rather than in the ground if possible, as this could help to contain unwanted spreading.

This plant is also capable of rooting where vines come into contact with the ground, even when it’s growing in a container, so keep a close eye on those trailing vines as well.

Let’s talk about planting from seed, rooting cuttings, and transplanting rhizomes.

From Seed

In late fall, when berries on existing plants have fully developed their deep blue-black tone, the seeds inside will be mature. It’s at this time that you can collect them.

Press seeds out of the berries and rinse to remove any fleshy material. Prepare a plastic zip-top bag by adding a couple handfuls of dampened peat moss and gently press the seeds in immediately.

Be sure the seeds are covered by the moss and don’t let them dry out, as they may lose viability.

Be sure to wash your hands thoroughly or wear gloves while handling the berries, as they are mildly toxic. Avoid touching your eyes or mouth after breaking them open.

Seal the bag closed and place it in the back of the refrigerator for at least sixty days to stratify, or provide a cold period that signals the onset of dormancy.

Later, when the seed is exposed to warmer temperatures, this will trigger germination.

After sixty days, prepare a flat or individual four-inch pots with a mix of one part peat moss to one part potting soil.

Press the seeds about one-eighth of an inch deep into the soil and lightly cover them. Moisten the soil, and keep it consistently moist.

A combination cell tray and dome works well for starting seeds, such as this 12-cell seed starting set available from True Leaf Market.

Place the tray or pots in a warm location and cover it to keep the soil warm. A plastic storage tote also works well, or you can cover pots with plastic. Be sure the tray or pots are receiving five to seven hours of indirect sunlight per day.

Seedlings should sprout within one to two weeks. After the last frost for your area, begin moving the seedlings outdoors for two to three hours at a time, avoiding exposure to direct sunlight at first.

Increase the amount of time they’re left outside daily, and gradually move them into more direct sunlight. After about a week they’ll be ready to transplant to their permanent location.

Alternatively, you can direct sow seeds in the ground or an outdoor container after the threat of frost has passed and skip the process of moving them outdoors gradually to harden off.

Whether the plants will be grown in the ground or in a container, look for a location that offers at least partial shade, as this can help to curb unbridled growth. The site should have good drainage and a sturdy structure that the vine can climb.

Use the same ratio of potting mix to peat, or add one part compost if you plan to plant in a container. Prepare a hole as deep as the root system and twice as wide, and place the seedling in it.

Press the soil with your hands to compact it a bit, and water deeply. Allow the soil to dry out between watering as this can also help to prevent overgrowth.

From Cuttings

Cuttings can be rooted in late spring through summer. Begin by choosing a few healthy vines and cut the ends with sharp pruning shears at about four-inch lengths. Each cutting should have several leaves.

Place the cuttings in water while you prepare individual four-inch pots or a flat of cells filled with a mix of one part potting soil and one part peat moss. Moisten the soil but do not soak it.

Remove the lower set of leaves from the stem of each cutting and dip the cut end into a powdered rooting hormone, if desired.

Press each cutting into the soil deep enough to cover the first set of leaf nodes, but do not compact the soil around the stems.

If you’re using a single open tray for rooting, be sure to leave several inches of space between cuttings to avoid root tangling as they develop.

Place the pots or tray inside a lidded plastic storage tote, or bag each pot individually in clear plastic zip-top bags to keep the growing environment warm and humid, as this will help to encourage rooting.

Monitor the moisture level to be sure the potting medium feels damp at all times, as cuttings will not root in dry soil.

Move the pots or tray to an area where the temperature is a consistent 65 to 70°F, with six to eight hours of daily exposure to indirect sunlight. Roots should begin to develop within two to four weeks.

Plants will begin to show signs of new growth after roots become established.

When new growth begins to appear, move the plants outdoors in full to partial shade for two to three hours at a time per day, gradually increasing the length of time they’re left outside and the exposure to direct sunlight.

After five to seven days of outdoor exposure, the plants will be ready to transplant to their new home, whether in the ground or in an outdoor container.

Be sure that the planting site has adequate space and a structure to support this climbing vine, unless you plan to plant it as a ground cover instead.

If so, be sure the site has good drainage, and allows for easy access for pruning and maintenance.

Choose a site that doesn’t have strong sun exposure; partial to full shade will prevent this vine from growing so quickly.

Prepare the planting site with a hole of about the same depth and about twice as wide as the root system. If you’re planting in a pot, use a mix of one part peat moss to one part potting soil as the planting medium.

Place the plant into the hole and backfill with soil. Press the soil around the base of the plant to compact the soil, and water well to settle it in.

From Rhizomes

Japanese honeysuckle roots spread through the ground, forming a rhizomatous system.

The bulbous roots can develop quite a distance from the parent plant – sometimes more than ten feet away – and will produce shoots of new growth there. Roots can be found from the soil surface to a depth of 12 inches or more.

If you’ve come upon shoots that you’d like to dig up and relocate to the planting site of your choice, simply bring a plastic zip-top bag with you and add a few wet paper towels to prevent the roots from drying out.

Carefully dig the rhizome out of the soil, being sure to leave as many of the fibrous roots intact as possible. Immediately place it in the bag and seal it on either side of the stem.

You may notice that the plant begins to wilt quickly, so don’t wait to get it back into the ground.

Bring the plant to the new site, and prepare a hole as deep and twice as wide as the root system. If you plan to plant it in a container, use a mix of one part potting soil to one part peat moss.

Place the rhizome in the hole and backfill around it with soil. Press the soil gently to compact and water well to settle it in.

If the plant has shown signs of wilt, be sure to keep the soil very moist, but not soggy, until it perks up. You may also want to provide some shade from harsh sunlight for the first few days to allow it to acclimate to its new site.

How to Grow

Once you’ve got your honeysuckle vine planted, you’ll find caring for it is exceedingly simple, with the exception of containing overgrowth, which we’ll cover in the section on pruning and maintenance below.

When growing in the wild, this species of honeysuckle crops up from disturbed ground in both the forest and field, and will tolerate soil that other plants would wither and die in.

Dry, compacted, salty, prone to flooding, nutrient-deficient – this vine can handle it.

However, loamy soil is preferred, but can also promote overgrowth, so soil that has some available organic nutrients and adequate moisture is best.

The soil should have a neutral pH, and low clay, as heavy clay soils are less nutritive and can negatively impact plant roots.

The planting site you choose should not have strong sun exposure, as partial shade can help to slow growth. It should also be well-drained, as allowing the soil to dry out between watering can keep the vine in check.

Rainwater can provide adequate moisture without the need for additional watering, unless your area is experiencing drought conditions. In this case, plan to offer about one inch of water per week.

Avoid planting this vine near other plants if possible. Studies suggest that this plant is allelopathic, or capable of producing chemicals that spread through the ground to inhibit the growth of other adjacent plants.

Detrimental effects have been observed in some varieties of pine tree in particular, when exposed to these chemicals.

The same needs apply to both a container-grown plant and those growing in-ground: allow the soil to dry out between watering, keep it in a shaded location, and be sure to prune back new growth.

For container-grown plants, a pot that is twice as deep and wide as the root system will allow for comfortable growing conditions.

If you’re using the vine as a ground cover, plant one to two plants per square yard of ground and leave at least eight feet of space between them.

While it’s not entirely necessary to fertilize a honeysuckle vine to improve growth, you may want to feed it to improve blooming.

A granular fertilizer that is formulated for flowering vines, such as Nelson Nutri Star plant food, available from the Nelson Plant Food Store via Amazon, can be sprinkled on top of the soil above the roots of the plant and raked in gently.

Granular fertilizers work well for outdoor plants as they release nutrients slowly over time, and reduce the likelihood of over-fertilizing.

Apply according to the package instructions, with the first application in early spring, and once every thirty days throughout the blooming season. Water well after each application to distribute nutrients and prevent the buildup of salts in the soil.

Liquid or foliar fertilizers can also be used, but be sure to look for fertilizers with a balanced ratio as they will improve both bloom and foliage growth.

If your vine is growing vigorously and blooming well, there is no need to add fertilizer.

Growing Tips

- Provide a shady growing environment and allow the soil to dry out between watering to keep growth in check.

- Plant vines in a container whenever possible to reduce spreading of rhizomes into neighboring ground.

- Keep a close watch on Japanese honeysuckle vines to prevent unwanted spreading.

Pruning and Maintenance

As this is a vine, you’ll want to be sure that you provide adequate space and support for it, unless you are growing it as a ground cover.

Vines can reach as much as thirty feet in length, but they can and should be pruned back as needed.

A strong trellis is suitable; however, be sure that the vine is not growing in close proximity to other plants or structures, like the siding on your house, or plan to prune continuously throughout the growing season.

If it wraps around adjacent plants, or spreads underneath siding, in between trim, or along a fence, it can cause damage.

Woody vines of this nature can also become very heavy after years of continuous growth as the stems thicken. Don’t underestimate the weight of a mature vine as it can easily pull down a structure that is not sturdy.

Pruning can be done at several different times throughout the year. Avoid cutting off blooming stems in the spring, but cut back any errant vines that are reaching outside of the area they belong in.

To prune, use a set of sharp, clean garden shears and remove new growth as needed. Look for stems that have fewer blooms to cut back first. This will allow the plant to divert energy to the support and health of older growth.

In midsummer to early fall, plan to prune again. Remove dead or dying parts of the plant, and if it has gotten very dense, cut a few longer lengths back to open it up, as closely growing foliage can harbor pests and mildew.

Avoid cutting back the primary trunks of the plant unless absolutely necessary.

If you live in an area where winter is harsh and extremely cold, the vine may drop leaves rather than remaining evergreen. You can cut back dormant stems when the leaves have dropped to promote fresh growth in the spring.

As this plant is extremely hardy and grows well in Zones 4 through 9, winter cold protection is not typically necessary.

Pruning should not be neglected, even when this species is chosen as a ground cover. Plan to cut back several inches at a time to control spreading, every few weeks between spring and fall.

In the winter, shear the plants back to ground level to remove dead material from underneath, allowing a fresh start in the spring.

Any shoots that have escaped outside of the area you intended for them to grow in will need to be dug out. Do your best to remove all of the rhizomes from the soil and keep an eye out for more shoots popping up in the surrounding area.

It’s possible to miss some rhizomes or stems, and if this happens, be prepared for vigorous regrowth. Continue to remove new shoots and look for roots if this happens.

Be sure to dispose of any rhizomes, raked or picked up trimmings, dropped berries, and other plant material, to avoid sprouting or rooting in unintended areas. Place them in a tightly sealed trash bag.

Do not dispose of pruned plant material or rhizomes in the compost pile, or with other yard clippings in a dump pile, as they are likely to continue to root and grow in places you didn’t intend for them to be.

To reiterate – it’s strongly advised to plant this vine in a pot or planter where it can be contained, as rhizomes can spread through the ground, releasing it into environments where it can cause damage.

Cultivars to Select

There is only one cultivar of Japanese honeysuckle sold in North America, and that is L. lonicera ‘Halliana,’ aka ‘Hall’s Prolific.’

Plants are available from Nature Hills Nursery.

Managing Pests and Disease

Japanese honeysuckle is rarely troubled by insects or disease. It’s extremely resilient, and even when affected by the snacking of browsing wildlife, it bounces back and continues to grow.

The primary pests are easily treated when signs of infestation are spotted early.

It’s also important to treat infestations, even if they don’t pose a threat to this vine, because pests can readily spread to other garden and landscape plants.

Herbivores

If you’re anything like me, you expect some furry, hungry woodland friends to visit your yard from time to time. But, as previously mentioned, this vine can take a bit of munching without too much of an impact.

Deer

There aren’t many plants that deer won’t nibble in the cooler months of the year when it can become difficult to find forage.

However, if you live in an area where they’re searching for food because temperatures are very low, most likely your honeysuckle will have already gone dormant and dropped its leaves.

Spotting signs of damage caused by deer can be a little annoying, but bear in mind that this vine will bounce back with a vengeance when spring comes around.

If you’re still concerned because you have a large number of deer visiting your property, you can plant your vine in a container and move it out of harm’s way when necessary.

Read more about dealing with deer in the garden here.

Rabbits

I think I’ve added rabbits to almost every list of garden pests I’ve ever compiled. They’re seemingly ever-present in much of the world, and always voraciously seeking their next meal.

Just as with deer, it’s unlikely that they’ll cause enough damage by browsing to have any detrimental effect on your vines. In fact, after some moderate nibbling, your honeysuckle will compensate by boosting new growth.

If rabbits become a major problem, fence off your garden area or move plants to an inaccessible place in your yard.

Insects

Pest insects are a fact of gardening that most of us are woefully familiar with, but the Japanese honeysuckle vine is so hardy and resilient that it’s highly unlikely that most pests will cause enough damage to kill it, or even slow it down.

The real issue with any infestation is that it can potentially spread to other garden or landscape plants, and in those instances, pests can not only devour your plants but they can hinder healthy growth by spreading disease as well.

Plan to take quick action if signs of infestation become visible.

Aphids

These tiny, pear-shaped little nuisances range in color from nearly transparent white to bright flame red. They can show up on garden and landscape plants at almost any time of year, and are found all over the world.

There are more than four thousand species of aphids currently known, and all of them feed on various types of plants by piercing the exterior and sucking the fluids from the inside.

While they’re tiny and probably seem like a mild annoyance, they can consume a lot more than you’d expect, which can cause stunting and eventual plant death.

Look under leaves and along stems for the presence of aphids. If you notice leaves curling, turning yellow, or wilting, do a visual once-over to make sure these guys are not the culprit.

Also note that the presence of ants on blooms and traveling across stems and leaves can signify that there are aphids present, as the two species have a symbiotic relationship.

Treat aphids with an application of neem oil according to package instructions, a blast of water from the garden hose, or by pulling on a pair of gloves and smashing the ones you see.

After treatment, keep an eye out for any hatchlings that may come from eggs that have already been laid.

While aphids can cause significant damage if left untreated, the honeysuckle vine is ready to fight back, producing new shoots and foliage in response as long as it’s otherwise healthy.

Learn more about identifying and treating an aphid infestation in our guide.

Caterpillars

Many plants play host to caterpillars of one species or another every season.

If you live in a place that’s part of a migratory route for certain species of butterfly or moth, like monarchs, you may even plan to include plants in your garden to help support them in their travels.

Honeysuckle is a plant that is known to attract over a dozen different types of Lepidoptera, or the order that butterflies and moths belong to, and all of these species are beneficial to the environment in some way.

Just as with other insects, caterpillars can cause quite a bit of defoliation, munching their way toward the next phase of their lives as they prepare to pupate.

Most are fairly visible both in size and color, and signs of their presence can include discoloring; holes chewed along edges of leaves; and frass, or wet, gooey droppings on leaf surfaces.

As the adults are also important pollinators, it’s best to try to relocate the larvae if they’re causing significant damage.

You can pull on some gloves and move them into a container, then bring them to another area where they can continue to look for forage.

Even after completely stripping the foliage from much of a given honeysuckle vine, it’s likely that the plant will bounce back in full force to compensate for the loss.

Scale

Small, dome-shaped “shells” are characteristic of scale insects. There are many species, and they range in color from a plain tan-brown to shimmering gold.

They’ve been around since the time of the dinosaurs, and are found today in gardens and in the wild, all over the world.

Scale insects include armored, soft-bodied, and mealybug types. Adults of these species are mostly immobile, living their lives attached at the mouth to the underside of leaves, or in leaf margins.

Young scale insects are called “crawlers,” and they can be difficult to spot as they’re small and worm-like. By the time you see them, there are probably hundreds of eggs laid on other parts of the plant, as these insects are prolific breeders.

You’ll see leaves curling, discoloring, and wilting when scale insects are present. Other signs can include downy white, cotton-like nests, black sooty mold on foliage, and leaf and bud drop.

Infestations are not always easily treated. Neem oil or insecticidal soap applied according to package instructions can do the trick, but you may need to treat more than once to fully clear up an infestation.

These products can suffocate both crawlers and adults of the species, but you may need to thoroughly soak the plant to achieve this if you have a large infestation.

As their mouthparts pierce the plant to feed on the internal fluids, any plant disease they come into contact with can be spread easily to other plants.

Fortunately, as with other insects, honeysuckle is quite vigorous, and it takes a large, untreated infestation to cause significant damage.

Vine Weevils

Of all of the insects on this list, vine weevils have the potential to be the most destructive to the Japanese honeysuckle vine.

While they can be eradicated, and the damage they cause mitigated, if they’re present on a young vine, they can cause plant death in a short period of time.

There are a few different types of vine weevil, but the black vine weevil is the most common and widespread.

It’s found throughout most of North America, with the exception of the deep south of the United States and northern Canada.

Adults are shiny, black, and usually less than half an inch long. They feed on a wide range of plants, but ornamental vines and yew trees are most common.

When adults are present, you’ll see half-moon shaped notches with dead, brown borders along leaf margins. They typically feed after sundown and through the night, making them difficult to spot.

While notches are a visible indication of the presence of adults, it’s the larvae that cause the most damage to plants.

Adult vine weevils lay hundreds of eggs in the soil at the base of the plant.

The larvae hatch as tiny, curled, legless worms of a pale white color, with red-brown heads. They’re normally found in the soil at a depth of twelve to sixteen inches.

Larvae pupate closer to the soil surface, living there over winter and emerging as adults in the spring.

While in the larval stage, the worms feed on plant roots and cause girdling of the stems, essentially strangling the plant as nutrients are not able to flow freely through the stems and foliage.

Larvae can be difficult to treat as they can be present in the soil at almost any time of year, if adults manage to successfully live through the winter months.

You’ll notice that your vine begins to wither and die off. Foliage may turn brown or rust, and if your plant is growing in a container, a visual inspection of the roots will show significant destruction.

To rid the soil of a larval infestation, you can drench it well with beneficial nematodes such as the Steinernema carpocapsae or Heterorhabditis heliothidis species, but be sure that the soil temperature is at least 50°F, as neither species can survive in cooler soil.

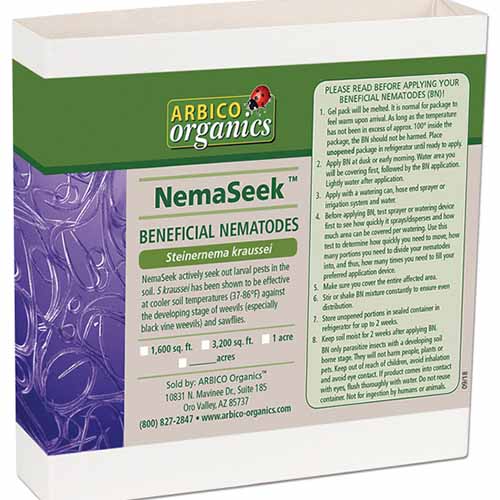

If you need to introduce nematodes in cooler temperatures, consider the Steinernema kraussei species, available as NemaSeek from Arbico Organics.

This species can effectively parasitize pests in temperatures as low as 37°F.

Nematodes attack organisms in the soil, entering their bodies and killing them as they reproduce. They’re effective against a number of soilborne pests.

Pesticides formulated for use on adult weevils can be used to prevent them from laying eggs as well.

Disease

As previously mentioned, it takes a serious infestation or illness to kill a honeysuckle vine.

There are only a few diseases that can become problematic enough to look out for, and a physiological condition not caused by a biological pathogen as well.

Canker

Canker is a disease that’s spread through water, such as standing water left behind after a heavy rain.

It’s caused by a fungus called Insolabadsidium deformans that targets wounded plants, so if your vine has suffered damage or had an infestation of pests, it’s more likely to present with canker as well.

When the fungus is present, you may notice yellow or brown leaves, black or brown spots on the underside of leaves or stems, and a generally unhealthy appearance.

If you can catch signs of this disease early, you have a good chance of stopping the spread by removing affected foliage.

Cut back as much as necessary using clean pruning shears, and be sure to sterilize the shears afterward. Dispose of infected material in a sealed trash bag and away from other plants.

Make sure there is no standing water present on the ground as this could cause recontamination.

Chlorosis

If the leaves of your vine are looking faded or begin to turn yellow, your first step is to make sure it has adequate moisture. If it does, then it may be affected by chlorosis.

Plants that are growing in soil that is nitrogen deficient may present symptoms of this type of physiological condition. Not a disease caused by an infectious pathogen, treating chlorosis begins with adding nitrogen to the soil.

Use a slow-release fertilizer applied according to package instructions, like the previously mentioned Nelson NutriStar granules, to slowly add nitrogen to the soil.

As the plant takes up the additional nitrogen, you should begin to see improvement. Cut away any plant material that is dead or dying to allow the plant to allocate energy to new growth.

Powdery Mildew

Even though it’s best to allow the soil your vine is growing in to dry out a bit between watering, a long period of drought can lead to the formation of powdery mildew.

You may also notice signs of the disease if the plants have been exposed to other affected plants.

This disease is characterized by powdery patches on leaves and stems. It’s caused by a fungus, and spores can be easily spread from one plant to another on the wind or by contact. New growth is more likely to be affected.

You’ll most likely see signs of powdery mildew appear in late spring or early summer in most areas, as the fungus spreads more easily in warm, dry conditions, although it does need some humidity to colonize.

It can quickly overtake the vine, but is unlikely to cause plant death if treated quickly.

Preventative measures include pruning to thin the vines and improve airflow, avoiding contact with other infected plants, moving the vine away from structures such as fences and walls where heat and humidity could worsen the infection, and removing any affected plant material and disposing of it in a sealed trash bag.

Any time when you have to prune off infected plant material, be sure to sterilize your pruning shears to avoid spreading illness to other plants.

Powdery mildew can be treated with a mixture of one tablespoon of potassium bicarbonate and one tablespoon of castile soap in a gallon of water. Spray the mixture over all plant surfaces.

Alternatively, a sulfur-based fungicide can be applied, however, be aware that over-application of fungicides can lead to resistance.

After treating the infection, trim away any affected dead or dying plant material caused by the disease, and be sure to keep the vine pruned back consistently to avoid overgrowth, which can cause reinfection.

Learn more about how to treat powdery mildew in our guide.

Best Uses

Japanese honeysuckle is more than just a pretty face. In fact, it’s fairly versatile, and even has some uses that you may not have heard of before.

Let’s get it out of the way first – if you’ve got honeysuckle growing in your yard or garden, you’ll probably pinch a blossom or two off for the occasional dab of nectar on your tongue.

If you’re like me, and grew up playing outside in those humid summer months, that nip of flavor will bring back many fond memories.

Just be sure to avoid any plants that have been sprayed with chemicals for edible enjoyment.

Coming in at a close second, this vine makes an excellent privacy screen, as it grows vigorously and densely in a short period of time. As long as you manage its growth, you can easily train it along a chain link fence.

If your property is part of a flood plain or is known to have erosion issues, you can create a kind of natural reinforcement, as the roots of this vine spread through the soil and hold it firmly in place, while putting excess water to use.

A patch of land where nothing grows could be the perfect place to create a flowering carpet of vines. As long as water is adequate, you’ll have a wonderful smelling ground cover in a short period of time.

The blossoms of this vine not only smell incredible, and taste sweet, but they can be pinched off in a quantity sufficient for steeping to make a tasty tea.

Pull about three-quarters of a cup of blossoms off of the vine when they begin to turn a deep yellow, and allow them to dry for one to two days.

Add the dried blossoms to two to three cups of hot water and allow them to steep until the water changes to a golden color. A teaspoon of honey can add a little extra sweetness, if desired.

If you’re a beekeeper or would like to offer forage for pollinators to visit while passing through your garden, there is no better vine than this.

Bees, butterflies, beneficial wasps, and hummingbirds are just some of the beneficial pollinators that would love to hop from bloom to bloom on a sunny day.

Plants that have been trained to grow on a trellis can create a shady, beautifully fragrant retreat on a balmy summer afternoon.

They can also be trained to grow over unsightly structures like concrete walls to add some beauty to an otherwise unappealing part of your yard.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Semi-herbaceous flowering perennial vine | Flower / Foliage Color: | White to yellow/green |

| Native to: | Eastern Asia | Tolerance: | Dry conditions, heat, salt, shade |

| Hardiness (USDA Zone): | 4-9 | Maintenance | Moderate |

| Bloom Time: | Spring-summer | Soil Type: | Loamy, low clay |

| Exposure: | Full sun to part shade | Soil pH: | 5.5-8.0 |

| Time to Maturity: | 2-3 years | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Spacing: | 15-30 feet | Attracts: | Bees, butterflies, hummingbirds, moths, wasps |

| Planting Depth: | 1/8 inch (seeds) | Avoid Planting With: | Other plants or trees |

| Height: | 30 feet | Uses: | Erosion control, ground cover, privacy screen, tea |

| Spread: | 3-6 feet | Order: | Dipsacales |

| Growth Rate: | Fast, 9-12 feet per year | Family: | Caprifoliaceae |

| Water Needs: | Moderate | Genus: | Lonicera |

| Common Pests and Disease: | Deer, rabbits; aphids, caterpillars, scale, vine weevils; canker, chlorosis, powdery mildew. | Species: | Japonica |

Bring the Scent of Summer to Your Garden

Are you willing to provide a little extra care to keep Japanese honeysuckle contained in exchange for the warm, heady fragrance of vanilla-scented blooms and the sight of bees, butterflies, and hummingbirds foraging in your garden?

Nothing says lazy summer days like a trellis full of fragrant blossoms providing shade overhead.

This vine may be the perfect solution to hiding that ugly chain link fence, or holding exposed soil in place on a large, barren hill – just be sure to research the laws in your area ahead of time to make sure it’s safe to plant it!

What creative methods have you found for growing this vine at home? Let us know – and share some pictures with us – in the comments below!

And to learn about growing other types of honeysuckle, check out these articles next:

Ridiculous article. Unless you have a hundred unused acres or so, no person in their right mind should plant the invasive Japanese honeysuckle plant. It ALWAYS gets out of control and will smother and kill all of your other trees, shrubs, and flowers which cannot compete with this monstrous plant.

Thanks for your input, Kort! I fully agree that gardeners should proceed with caution, and do their research. This species is considered invasive throughout a large portion of the US, as described in our article. But this is not the case everywhere. It can be managed, maintained – and enjoyed! – in certain climates and growing situations.

It simply can’t be controlled and should therefore not be planted anywhere. Had a bunch in my yard, hosting rats, when I first moved in 15 years ago. Still trying to get rid of the honeysuckle.

Japanese honeysuckle is considered a noxious plant in KS.

Yes, you can read more about the invasive nature of this plant across a significant portion of the US in the Cultivation and History section above. As recommended in our guide, it should only be cultivated thoughtfully and in accordance with local regulations.

My friend lived next door to someone who has it growing on their fence. It smelled SO incredibly wonderful! Being a neighbor, she only had to open her door wall to enjoy the benefits of this wonderful plant. Still enjoy this familiar scent, every time very much!

Hello Becky! Inhaling that scent is absolutely one of life’s simple pleasures. Thanks for this sweet reminder.

Japanese honeysuckle is also called bush honeysuckle and is not a vine . . . . I recommend that you go back to do more research.

Where are you located, George? I believe you are mistaken- Lonicera japonica is in fact a vine, and it’s regarded as invasive throughout a significant portion of the eastern US. There are several varieties of bush honeysuckles with an upright bush-like habit, including Amur (L. maackii), Bell’s (Lonicera x bella), and Tatarian honeysuckle (L. tatarica). These are also nonnative species and widely regarded as invasive in North America.

Do not. That is how you grow japanese honeysuckle. It’s an extremely invasive species that have reshaped a huge part of the biom in the USA. Cut it down when you see it.

This site is not exclusive to the USA. And if you’d actually read it, you would see the first half is basically a giant warning about the potential invasiveness.