Vicia faba

Fava beans are a cool-weather crop that will provide a bountiful harvest of plant-based protein – while also fixing nitrogen in your garden!

As a legume grown long enough that it’s often described as ancient, its extensive track record should give you confidence that it can be cultivated with ease.

In fact, when it comes to the history of agriculture, favas should be considered an elder, deserving of awe and respect – they have been used as a crop nearly as long as humans have been practicing agriculture.

Kind of mind-boggling, isn’t it?

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

Favas have certainly passed the test of time, but this is only one of the reasons why more gardeners should give them a try.

Beyond their ancient and toothsome allure, in my own garden I love the way they expand my roster of spring crop options, as well as their ability to serve as powerful companion plants.

Whether you grow them for their tasty beans, their ability to fix nitrogen, or out of sheer awe, favas will earn their keep in your garden.

We’re going to discuss how to grow these beans and take a look at some cultivars of interest, as well as techniques and ideas for getting them out of the garden and into our bellies.

And on that thought, I bet you’re ready to get started! The sooner we get growing, the sooner we get to chow down. Here’s a quick look at what we’ll cover:

What You’ll Learn

What Are Favas?

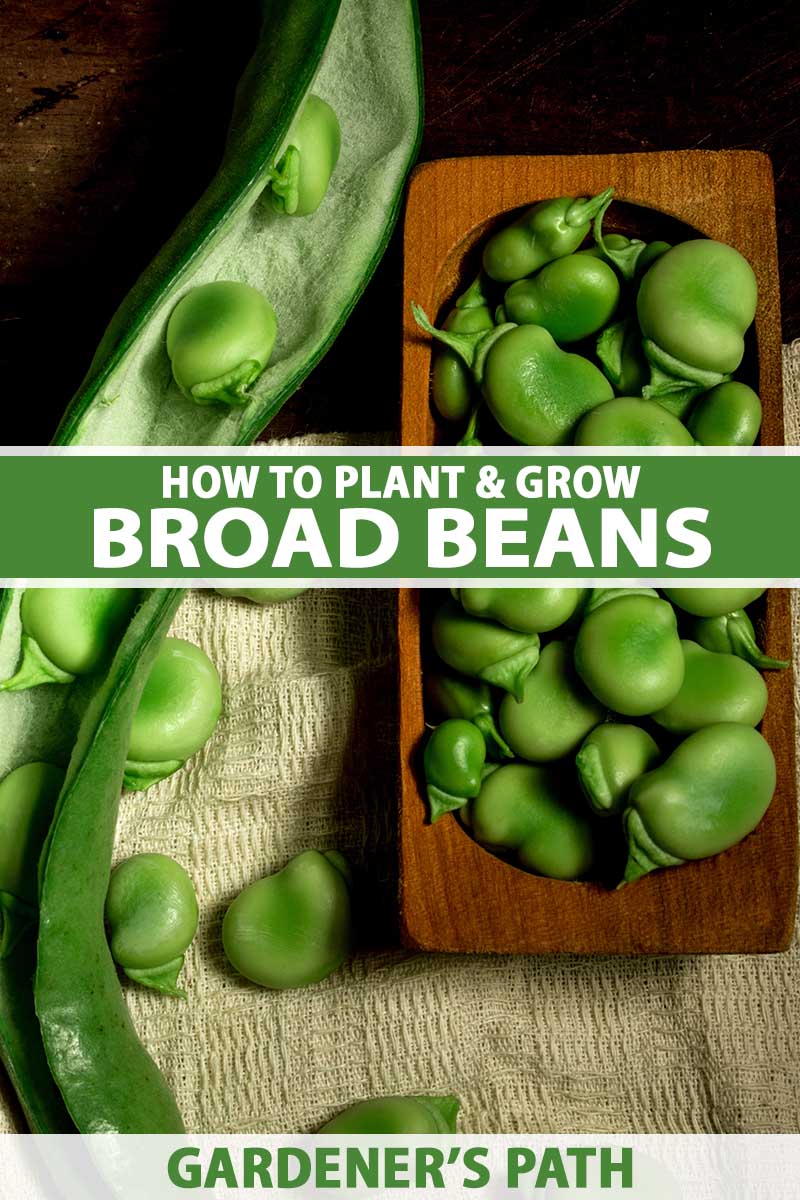

Favas are cool-season legumes known for their large, meaty beans.

Plants have an upright, non-vining growth habit and reach two to six feet tall, depending on the cultivar, with a spread of about 12 inches.

Their grayish-green leaves are large and compound with oval leaflets, while their striking flowers have a look of the orchid to them. They’re usually white with large purplish-black spots and nectar guides.

Some cultivars have brownish blooms, and one is even known for its unusual crimson hue.

Pods are green, and when ripe, they are rounded and plump. The pods of some cultivars grow up to 12 inches long.

And inside the pods are the piece de resistance – the delectable seeds.

Seed size and color vary depending on the type of fava grown, and they are usually described as falling into three main categories:

1. Vicia faba var. major is the one you will most likely be familiar with. Seeds are quite large, flat, and usually about an inch long.

2. V. faba var. minor, also known as tic peas, tick peas, or pigeon beans (not to be confused with pigeon peas). They produce small seeds about the size of lentils.

In addition to their culinary uses, they are also used for livestock forage. They are sometimes classified as V. faba var. minuta.

3. V. faba var. equina, or “horse beans,” have medium-sized seeds. Like tick peas, they are used for livestock forage, particularly for horses – hence their name.

These are also sometimes referred to as “baby favas.”

This article will refer primarily to V. faba var. major, which are the favas also referred to as “broad beans.”

Depending on the cultivar, broad beans can come in several different colors – white, green, tan, dark brown, or purple. They are most often tan or brown when purchased as a dry or canned pantry staple.

Dry seeds have a noticeable “hilum” or seed scar that is usually black.

Fresh broad beans have a pea-like flavor while the dried ones have a more earthy taste.

In addition to its use as a foodstuff, this legume can also be used as a winter cover crop or employed as part of a permaculture fruit tree guild.

Note: Some individuals have a rare, hereditary enzyme deficiency (called “G6PD deficiency”) known as “favism.” Affected individuals can develop serious health problems from eating favas.

Individuals with this genetic predisposition tend to have Mediterranean, South Asian, or Northern African heritage.

For those with the enzyme deficiency, merely breathing the pollen from fava plants can be a risk and all contact with these plants should be avoided.

Cultivation and History

Classified as Vicia faba, this species is a member of the Fabaceae or legume family, with relatives including green beans, lentils, peas, alfalfa, limas, and many other important crops.

The wild ancestor of this species no longer exists in the wild, so its precise native range is unknown.

However, in a paper published in Scientific Reports in November 2016, Dr. Valentina Caracuta and colleagues at Haifa University in Israel announced an important discovery regarding V. faba.

These researchers discovered the remains of a wild fava ancestor dating to 14,000 years ago at a hunter-gatherer archeological site in Israel – indicating that the species is native to that part of the Mediterranean region.

Guess how they knew for sure that the remains were actually favas?

Remember that seed scar I mentioned a few paragraphs ago? It turns out that the fava has a distinctive hilum, and this is what allowed the researchers to identify the ancient bean with certainty.

Collected 14,000 years ago, this bean wasn’t yet being cultivated – that time period predates agriculture.

Meanwhile, our human ancestors transitioned from nomadic hunters and gatherers into sedentary farmers.

And by approximately 10,200 years ago this humble bean had become a crop to be sown and harvested, and its seeds saved for the future, making V. faba one of the oldest species domesticated for agricultural purposes.

Moving forward quite a bit in time, this legume was mentioned by Homer in the 8th century BCE, and by Pythagoras in the 5th century BCE. Perhaps already wise to the dangers of favism, the latter reportedly warned his followers not to eat this delicious bean or to even walk through fields of favas.

Members of the fava genus, Vicia, are known commonly as “vetches,” putting this legume in good company when it comes to fixing nitrogen in the soil. Like its vetch relatives, V. faba is often used as a green manure or as a nitrogen-fixing cover crop.

You can learn more about how to put broad beans to use in this way in our article on cover crop tips, tricks, and techniques.

And from a purely ornamental point of view, this plant can play many different roles, such as being used in a children’s garden or incorporated into an old-fashioned cottage garden.

But surely its most compelling use is in the kitchen!

Also known as “faba” beans, this legume is an important staple not just in Middle Eastern cuisine, but also in the culinary traditions of Southern Europe, Asia, and even Latin America.

We’ll dive more into the appetizing culinary uses of broad beans later in the article. First, let’s dig into how best to grow this staple.

Propagation

The best method for propagating broad beans is to sow these directly into the soil.

These beans require cool growing conditions and can be grown as a winter crop in southern climates, or a spring crop in more northerly locations. Spring crops can be planted as soon as the soil can be worked.

Depending on the cultivar you choose, whether you sow in spring or fall, and at what stage you harvest your crop, favas can take 70 to 220 days to reach maturity, with spring-sown crops growing more quickly than those grown over the winter.

If you’re concerned that you may not have time to bring these to maturity because of a short growing season, rather than starting them indoors and transplanting them, choose a short-season cultivar.

You’ll learn about your options a bit later in this article, so keep reading!

Whether sowing in early spring or in fall, broad bean seeds should be inoculated with Rhizobium leguminosarum to assist in nitrogen fixation before planting them in a particular area for the first time.

Planting areas already inoculated in the past few years won’t need inoculation. If in doubt, go ahead and reapply the inoculant.

Rhizobium Leguminosarum Inoculant

You can find R. leguminosarum inoculant at True Leaf Market in a variety of package sizes.

Learn more about using inoculants with legume crops here.

When you’re ready to sow, work some compost into your soil.

If the weather has been dry, I like to water my beds the day before planting, so the soil is moist but not soggy.

Sow seeds one to two inches deep and four to six inches apart. For square foot gardening, growing one plant per square foot is a good rule of thumb.

I like to use a pencil or my finger to poke holes in the soil and then drop the seeds in one at a time, then close up the holes with soil.

Experts at Oregon State University’s College of Agricultural Sciences recommend withholding additional irrigation until two weeks after sowing seeds to encourage growth and prevent root rot.

Be sure to note your sowing date in your gardening journal so you’ll have an idea of when the really fun part comes – the harvest!

In addition to noting the date you sowed the seeds, you might also want to refer to the “days to maturity” listed on your seed packet and note the estimated harvest date.

How to Grow

Favas aren’t fussy plants but will grow best when offered their ideal conditions, starting with full sun.

As for soil, this crop does best in silty loam but will also produce well in sandy loam. Either way, it requires good drainage, and the soil pH should fall between 6.5 and 9.0.

As for water, broad beans will need approximately one to two inches of water per week, depending on the temperature. Water in the morning instead of at night to reduce the risk of disease spread, and be sure to only apply water at the soil level.

Wondering if your climate is compatible with these nitrogen fixers? Favas are cold hardy, with some varieties able to resist damage to a mild 25°F, and others holding up unscathed at 0°F.

Whether you sow them in early spring or fall, you’ll definitely want to provide them with cool weather.

If you live in a tropical climate that doesn’t have a cool season, consider growing a warmer season legume instead. Check out our guide to growing different types of beans to find the species that will work best in your climate!

Growing Tips

- Grow in full sun.

- Make sure soil drains well.

- Direct sow as a cool-weather crop in early spring or fall.

Maintenance

Favas don’t require much maintenance – in fact, these tasks can be boiled down to two or three garden chores: weeding, mulching, and perhaps, staking.

Especially while young seedlings are getting established, keep weeds down around your crop to reduce competition for resources.

Need tips on how to make weeding easier? We have some for you right here.

Mulching is one way to keep the weeds at bay, and it will also help with water retention and prevent soil erosion.

You have many different options when it comes to mulch – learn about them in our article.

Another way to make maintenance easier is to create a polyculture garden layout, using ground covers as living mulches to help suppress weeds.

Weed management is one of the scientifically backed benefits of companion planting – read our article to learn more about how to use this technique in your garden.

Some broad bean cultivars can grow to be rather tall, and may require staking in some cases.

The style of trellising system used for tomatoes called “the Florida weave” works well for this crop – find instructions for making your own Florida weave in our article.

As for fertilizer, as long as your seeds were inoculated, your favas will be able to supply their own nitrogen thanks to the help of Rhizobium bacteria, and will not typically need any additional amendments.

However, to make sure your soil doesn’t have any deficiencies, consider doing a soil test.

Cultivars to Select

When choosing a cultivar, be sure to select one that works with the length of your growing season as well as any other climatic limitations you are working with.

Since these legumes can be sown in spring or fall, they often have two different estimated time frames to reach maturity – a shorter one for spring-grown crops, and a longer one for those sown in fall. If only one is listed, assume this is for spring-grown crops.

Here are some recommended options:

Aprovecho

‘Aprovecho’ is a cultivar of V. faba var. major that bears nine-inch-long pods, containing tan seeds.

Plants reach three to four feet tall with spring crops reaching maturity in 110 days.

This variety was bred by Ianto Evans of the Aprovecho Research Center.

Vroma

‘Vroma’ is a prolific cultivar of V. faba var. major.

Pods are six and a half to seven inches long, containing four to five light brown seeds each.

Plants require 75 days to maturity for a spring crop, have good resistance to aphids, and are heat tolerant.

Find ‘Vroma’ seeds for purchase from David’s Garden Seeds via Amazon.

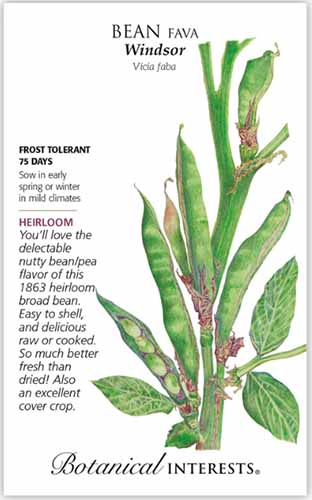

Windsor

‘Windsor’ is an heirloom English cultivar of V. faba var. major dating back at least as far as 1863.

Pods are five to six inches long, bearing three to five one-inch seeds each, which dry to a brown color.

Plants reach two to three feet tall, maturing in 75 to 85 days for a spring harvest, and are cold hardy to 12°F.

You’ll find ‘Windsor’ favas available for purchase in packs of 18 seeds at Botanical Interests.

Want More Options?

Managing Pests and Disease

Many gardeners grow broad beans without any worry from pests or diseases, but it’s always good to prepare for the worst and be pleasantly surprised when all goes off without a hitch.

Here’s what you’ll need to watch out for:

Herbivores

Favas make good livestock forage, and that means they are just as attractive to other hoofed mammals, such as deer. To prevent these ruminants from treating your crop as an all-you-can-eat-buffet, you can try deer fencing.

But fencing isn’t the only strategy you can use – get other tips for deer-proofing your garden in our article.

And since broad beans are a cool-season crop, they may serve as prime eating for those other fans of cool, moist weather: slugs and snails.

There are many natural methods you can use to protect your garden from slugs and snails – learn more in our article.

Insects

When growing these legumes, the presence of small populations of herbivorous insects is nothing to worry about. However, if an infestation breaks out, you may need to take action. Here are some pests you may encounter:

Aphids

If you suddenly notice ants crawling all over your fava plants, take a closer look – you might have aphids.

Since ants have a special relationship with these little pests, tending to them almost as livestock while they collect their honeydew, you might notice ants before you notice any aphids, which may be hiding on the undersides of leaves.

Aphids are tiny insects that pierce plant tissue to suck out nutrients, weakening plants and often spreading disease from plant to plant as well.

While a strong jet of water from the hose is sometimes all that’s needed to say “bye-bye” to aphid guests, sometimes you need other options.

Learn more about managing aphid infestations in our article.

Pea Weevils

One of the most insidious types of pests that attacks this crop is the pea weevil.

These somewhat misnamed pests are not actual weevils (from the superfamily Curculionoidea), but are in fact a type of leaf beetle from the family Chrysomelidae.

Field peas are pea weevils’ favorite food – but their next favorite is favas.

When crops are infested, the larval form of this beetle grows inside a developing seed, using it as food while it grows, usually unnoticed. Gardeners may be surprised to harvest their crops and find holes chewed in the seeds where adults have emerged, ruining the beans.

Prevention is the most effective means to stop an outbreak of pea weevils. You can learn more about preventing and controlling pea weevil infestations in our article.

Root-Knot Nematodes

Related to beneficial nematodes but falling on the side of foe rather than friend, root-knot nematodes are tiny, worm-like organisms that infest the roots of garden plants, feeding on tissue and preventing plants from taking up water and nutrients properly.

Recognizing the signs of a root-knot nematode infestation is tricky.

While galls form on roots underground and out of sight, gardeners may not notice a problem until plants wilt, turn yellow, or exhibit stunted growth – all symptoms which can designate the presence of other pests or diseases as well.

Learn how to control root-knot nematode infestations in our article.

Disease

Disease in the garden is best avoided through prevention. Keep reading for tips on warding off diseases in your fava crop, and learn what to do in case of infection.

Chocolate Spot

Though it may sound as appealing as a tiny cacao treat, chocolate spot is a disease that can affect V. faba. It is caused by Botrytis cinerea and B. fabae, two fungal organisms.

Signs of chocolate spot include small, reddish-brown lesions on plant foliage, but also sometimes on stems and pods.

This disease is most likely to occur during periods of high humidity in overcrowded plantings.

Proper spacing ensures adequate airflow and providing it is an important step in preventing fungal diseases such as chocolate spot.

For those gardening organically, a non-toxic product such as neem oil can be used to treat a fungal infection, though neem oil can kill beneficial insects and should only be used in the garden as a last resort.

Another way to fight these fungal pathogens is to use another type of fungi – Trichoderma.

Learn more about fighting fungal pathogens with Trichoderma in our article.

Downy Mildew

Have you noticed brownish-yellow spots on your fava foliage? If so, downy mildew might be to blame.

Downy mildew is caused by a microorganism called an oomycete or “water mold.”

The type of downy mildew that affects legumes is caused by Peronospora viciae. This plant pathogen can damage broad beans in the same way that P. parasitica, another pathogen that causes downy mildew, can damage turnip crops.

These microorganisms flourish when temperatures are low and humidity is high, so for prevention, allow adequate spacing between plants to encourage airflow around your crop.

While downy mildew isn’t technically caused by a fungus, infections can be treated with fungicidal neem oil, such as Theraneem’s Neem Oil for the Garden. It’s available in 16-ounce bottles of concentrated neem oil from Amazon.

Theraneem Neem Oil for the Garden

Neem oil is often sold as a concentrate and must be mixed with water and a non-toxic dish soap before applying.

Follow the manufacturer’s instructions for mixing and applying this product, and keep in mind that while non-toxic to humans and pets, neem oil can kill beneficial garden insects as mentioned above.

Powdery Mildew

Powdery mildew is a fungal disease that will show up as a white or gray, powdery-looking substance on your plants’ foliage.

Like downy mildew, this disease is more likely to occur when temperatures are mild and humidity is high.

As with the other diseases discussed in this article, one of the most important steps you can take to prevent it is to ensure adequate spacing between plants. This will encourage airflow, reducing the amount of humidity that builds up around plants.

You can learn more about treating powdery mildew with homemade and organic remedies in our article.

Harvesting

Favas mature in 70 to 220 days, depending on whether you sow them in spring or fall, the variety you choose, and the stage at which you pick them – so refer back to your gardening notebook and seed packet to know when your harvest date is approaching.

When it comes to harvesting, you have three options. You can:

- Pick young favas in their edible pods.

- Harvest fat, green pods for shelling fresh seeds.

- Wait until the pods have dried and harvest dry seed.

While young, immature pods are edible, they aren’t really the main attraction when it comes to favas. Broad beans will give you the most bang for your buck when you let the seeds mature.

However, harvesting immature favas can be useful at the end of the growing season if there are still some small pods on your plants and temperatures risk plummeting below your cultivar’s cold hardiness limit.

Use a pair of scissors to snip pods from the stems.

For fresh shellies, let the pods plump up and turn glossy with seeds bulging inside them. To know if your pods are fully grown, you can refer to the mature pod length on the seed packet.

At this point, the pods themselves will be fibrous. It’s best to compost them or feed them to your chickens, while saving the fresh favas for the kitchen.

Your next option is to allow the pods to dry on the plant – which is how you’ll get dry favas for longer term storage, or for sowing next year’s crop.

Watch for pods to turn brittle and black. At this point, they should be dry enough to harvest.

When harvesting dry favas, hold a basket or paper bag below the pod to catch the seeds, since very dry pods can shatter when handled.

Beans aren’t the only edible feature of this plant – they also have edible flowers and foliage! Learn more about using the edible greens of these legumes in our article. (coming soon!)

Shelling and Peeling

Unless you are enjoying your broad beans in their immature form, you’ll need to shell the beans from their fibrous pods before you can eat them.

Fava pods have strings running down their seams – pull one of these and pry the two halves open, then pluck each seed from the pod.

Once the seeds are removed from their pods, you may also want to remove the seeds’ skins.

Favas have a thin outer skin or coat called a “pericarp.” This outer coat gives fresh seeds a waxy appearance and is usually removed before eating.

While young favas in their pods are tender and don’t need to be peeled, mature favas develop a tougher skin. Most cooks tend to remove these skins, though some chefs think the skin imparts a lot of earthy flavor to the bean and prefer to leave it intact.

As for dry favas, tick pea and horse bean types have skins that will become tender during cooking. The coats of larger types remain tough and are usually removed after cooking.

One of the easiest methods of peeling the skins from fresh favas is to freeze them for a half an hour, then return them to room temperature. The skins can then be easily removed.

On the other hand, if you plan to store the beans in the freezer, leave the skins on and remove them just before cooking. The extra skin layer can help protect them from freezer burn.

Another method to peel seeds is to blanch them in boiling water for three to five minutes, then shock them in an icy water bath. The skins will be easy to remove after completing this process.

Once you remove the skins, they will no longer have a waxy appearance.

Remember, this process is intended for fresh, mature seeds. Young favas in their still-edible pods don’t need to be shelled or peeled. And as for dry broad beans, you’ll want to soak them, cook them, and then remove their skins.

Preserving and Storage

Fresh beans will keep for up to two days in the fridge.

For longer term storage, they can be frozen – blanch them first in boiling water for three minutes, then shock them in a cold water bath. Drain well, then place them in an airtight container and freeze. They’ll keep in the freezer for up to three months.

Another means of preserving fresh favas is to pickle them through lactic acid fermentation. If fermentation isn’t yet in your repertory of skills, you’ll find a recipe for lacto-fermented garlic dill pickles at our sister site, Foodal. Just switch out the cukes for favas.

Finally, fresh broad beans can also be canned using a pressure cooker. A water bath canner isn’t best suited to the job though, since this is a non-acidic food.

If you’re new to pressure canning, make sure to read this guide to getting started with canning your own foods at home. You’ll find it at Foodal.

Dry broad beans are by far the easiest and longest-keeping option for storage.

Spread dried seeds in a single layer in a cool, dry place to ensure they have fully dried before storing them. Test seeds for dryness by trying to bend one – if it’s still flexible, it needs more drying time.

Once they are fully dry, store them in well-labeled, airtight containers in a cool, dry location for later use.

Recipes and Cooking Ideas

Fresh pods or shellies only require short cooking times, while dry seeds need to be soaked for several hours and then cooked.

Larger beans need longer soaking and cooking times than smaller ones. Dry beans that require removal of skins should be cooked in two steps – once to remove the skins, and in the final recipe after they’ve been prepped.

Since favas can be enjoyed at different stages – podded, fresh shelled, or dried and rehydrated – there are a multitude of different ways to eat them.

Traditional recipes featuring favas are found in Northern and Southern Europe, the Middle East, Northern Africa, Asia, South America, and Central America. The home chef could spend months, if not years, experimenting with this assortment of different recipes!

However, sometimes a home chef just wants to cook without a recipe, and while I love cookbooks, that is my usual mode of operation.

So, one of the easiest ways to add this legume to your diet is to throw the fresh pods or seeds into a soup with other fresh garden produce – just cook until the beans and other veggies are tender.

For those who prefer a recipe to guide them, why not indulge in some Italian-style inspiration? This recipe for fava bean fettuccine at our sister site, Foodal pairs fresh favas and pasta with poblano peppers, pine nuts, and pecorino cheese.

Finally, I can’t possibly bring up favas in an article without mentioning my personal favorite use for the dried legumes – ful medames, also known as ful or foul mudamas, or foul mudammas.

Ful medames is a popular traditional dish of the Middle East and one of the national dishes of Egypt, where it is often eaten for breakfast.

This preparation combines cooked, dried favas with flavorful ingredients like cumin, garlic, olive oil, and lemon juice.

The earthy flavors of the beans marry beautifully with lush olive oil and bright lemon – and the combination is simple but sublime.

There are many versions of this delicious dish, which is prepared in many different Middle Eastern countries.

In her cookbook “The New Book of Middle Eastern Food,” Claudia Roden provides a classic recipe for ful medames with many ideas for variations.

The New Book of Middle Eastern Food

You’ll find this instructive and mouthwatering cookbook available at Amazon.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Annual legume | Tolerance: | Cold |

| Native to: | Middle East | Maintenance: | Low |

| Hardiness (USDA Zone): | 2-10 | Soil Type: | Silty loam, sandy loam |

| Season: | Spring, fall | Soil pH: | 6.5-9.0 |

| Exposure: | Full sun | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Time to Maturity: | 70-220 days | Companion Planting: | Cabbage, kale, lettuce, potatoes, strawberries, sweet corn, Swiss chard, wheat |

| Spacing: | 4-6 inches | Avoid Planting With: | Other legumes |

| Planting Depth: | 1-2 inches | Family: | Fabaceae |

| Height: | 2-6 feet | Subfamily: | Faboideae |

| Spread: | 12 inches | Genus: | Vicia |

| Water Needs: | Moderate | Species: | Faba |

| Common Pests: | Aphids, leaf miners, Mexican bean beetles, pea weevils, root-knot nematodes, spider mites, thrips | Common Diseases: | Bacterial brown spot, broad bean rust, chocolate spot fungus, downy mildew, fava bean rust, fava bean necrotic yellows virus, Fusarium root rot, leaf blight, powdery mildew, sclerotinia stem rot |

Your Good Old Fava-rites!

Fava beans may be an ancient crop, but with so many different uses, I bet you’ll see them in a new light every time you grow and cook them.

Are you new to growing broad beans or is this one of your trusty old garden favorites? Let us know how you play with this crop in the garden or what you like to do with it in the kitchen – just drop us a note in the comments section below.

Interested in learning how to grow other nitrogen-fixing legumes? You’ll find more reading right here:

Great article, thank you

You’re welcome! Thanks for letting us know you liked the article!