Brassica oleracea var. acephala

There may be no vegetable more closely associated with the American South than collard greens.

Oh, wait, well, except maybe okra.

Regardless of which veggie is the most “Southern,” it’s not without reason that collards are the state vegetable of South Carolina, and cities in Georgia celebrate the collard green with annual festivals! The vegetable is considered a “must-have” dish on many Southern tables.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

Collard greens are well loved in other parts of the world too, with several African nations favoring the vegetable, as well as Brazil, Portugal, and the Kashmir region of Pakistan and India.

Interestingly, though it is known as a Southern favorite with excellent heat tolerance, it can also be grown in northern areas thanks to its frost tolerance.

Let’s discover more about this leafy green!

What You’ll Learn

What Are Collard Greens?

Collards are a member of the same plant genus – Brassica – that includes cabbage, kale, broccoli, cauliflower, Brussels sprouts, and kohlrabi, among others.

Collectively, these plants are often referred to as “cole crops.” You may also hear them called “cruciferous” vegetables or “brassicas.” The word “cruciferous” derives from “Cruciferae,” the former family name for what is now called “Brassicaceae.”

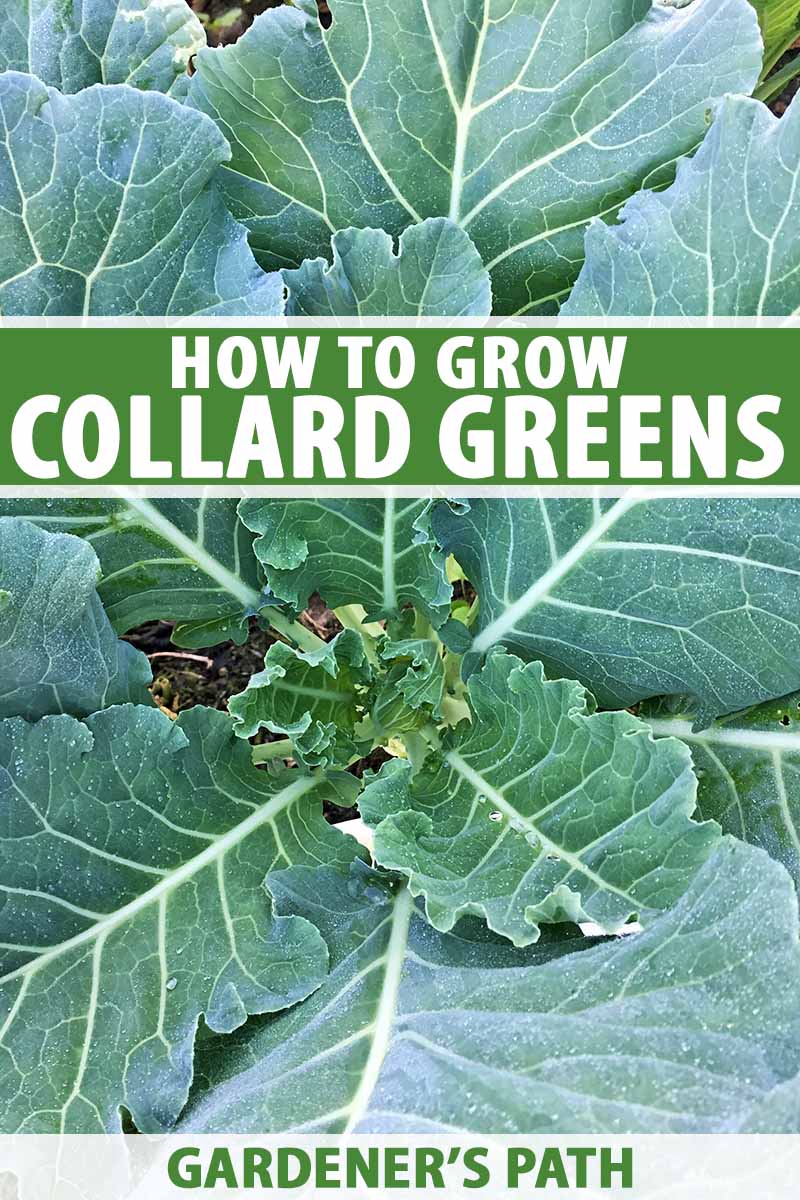

Plants in the Brassica genus come in many forms, with some, such as cabbage and Brussels sprouts, producing tight “heads” of leaves, while others, such as kale and collards, grow in a loose-leaf form. Cauliflower and broccoli produce loose leaves and dense heads of flowers, which are typically what we eat.

The collard’s loose leaf form means it is less susceptible – although not immune – to the fungal diseases that can plague plants in this genus. This is an important consideration for cultivation in the South, where high humidity offers fungal diseases a welcoming environment.

As a group, brassicas are appreciated for their nutritive value. Collards are high in fiber, manganese, folic acid, calcium, and vitamins A, C, and K, though some of their nutritional value can be lost through the cooking process.

In addition to having good heat tolerance (a definite plus in the South), these plants are also known for their preference for a cool growing season.

Collards can reach 20-36 inches in height and 24-36 inches in width. They’re hardy in zones 8-10, which means they’re perennials — which may live several years — in warmer regions. In other zones they may be grown as annuals

Cultivation and History

Likely descendants of ancient wild cabbages in Asia, collards as we know them today originated in the eastern Mediterranean. Ancient Greeks, for example, cultivated several types of collard.

Romans, too, cultivated and ate many leafy greens, including collards. As the Roman Empire spread west throughout Europe, east to what we now call the Middle East, and south to North Africa, they took collards with them.

It is unknown whether the Romans or the Celts – a collection of tribes with origins in Central Europe that predated Roman occupation of this region – brought collards to the British Isles.

From these widespread and various parts of the world, they eventually traveled to the American South. The plant was a staple of African slaves, and thus this leafy green began its history of importance in this region.

Backing up a bit, greens including collards were cultivated and consumed for their nutritive value throughout much of the African continent. Collards were a familiar and much-appreciated food source.

West Africans who were kidnapped and brought to American shores as enslaved people were often forced to forage for food, according to historians, and were likely relieved to find collards growing in winter, when other food was scarce.

Drawing on cultural wisdom passed down from their ancestors, the enslaved people knew that leafy greens were nutritive, a quality that must have been appealing to these people, who history teaches us were often malnourished.

The enslaved people put into practice the greens-cooking methods used by their forebears – they boiled them down until tender, adding available seasonings.

Typical flavorings during this period of American history included leftover, throwaway bits from the plantation’s main kitchen, such as ham hocks or pig’s feet, and those flavoring agents remain important ingredients in traditional collard preparation today.

Economically disadvantaged descendents of other nations who populated the American South also appreciated collards’ nutrition and ease of growth, and became heavy consumers of the leafy green, as well.

Passed down through the generations, cooking and eating collard greens has remained an important part of Southern culture to this day.

Propagation

You can start collard greens from seed indoors or outdoors, or you can purchase seedlings from a garden center and transplant them into your garden.

From Seed

Start seeds indoors four to six weeks before you plan to transplant outdoors. For a spring planting, you’ll want to transplant as soon as the soil has warmed to about 45°F, assuming you have enough time before air temperatures hit 85°F.

For a fall crop, you’ll need to figure out the time between a couple of light frosts and an all-out-killer freeze that will kill the plants, and back out your seed-starting according to the time-to-harvest information on the back of your seed packet.

Plant seeds at a depth of 1/8 inch. The seeds will take four to seven days to sprout.

Alternatively, you can direct sow outdoors using the same timing information detailed above. In general, spring crops are started indoors, whereas as fall crops are directly sown.

Though in some areas where it’s ever-lovin’ hot, even fall crops are started indoors while temps are still smoking and then transplanted when temperatures consistently drop below 85°F.

For direct sowing, seed heavily in rows 30 inches apart, and thin seedlings to 12 to 18 inches apart. You can discard, transplant, or eat the leaves of the seedlings you pull.

From Seedlings/Transplanting

When your seedlings are ready to plant out, or if you purchased some from your local nursery, you’ll want to set the plants in the soil at about the same depth to which they were planted pre-transfer.

Space them 12-18 inches apart, depending on the variety, and water well.

How to Grow

Collards prefer full sun, but will tolerate a few hours of light shade, and they have a few soil requirements:

- Deep

- Well-drained

- Rich in organic material

- Fertile

- Weed-free

As discussed above, collards are perhaps surprisingly one of the most cold-tolerant vegetables, able to withstand temperatures ranging down to the upper teens.

In fact, many aficionados swear collards taste better and sweeter after a frost or two.

Collards need about 80 days to mature from seed to harvest, but this can vary by variety, so check the back of your seed packet or plant pick.

Depending on where you live, you might be able to do a spring planting of collards, though these greens won’t have the benefit of a sweetening frost. Some gardeners can get both spring and fall crops in.

Collard roots can grow two feet deep, so be sure your planting bed has plenty of depth. Keep this in mind if you opt to plant in containers or raised beds.

Before planting, loosen the soil and amend with plenty of organic material, then scatter a 10-10-10 fertilizer over the planting area. Use about one cup of fertilizer for each 10 feet of row. Use a rake to mix the fertilizer into the top few inches of soil.

Another important criterion for growing collards greens is moisture. They need 1.5 to 2 inches of water weekly, so if Mother Nature doesn’t provide, you’ll have to supplement.

As the season progresses, you might need to scatter additional fertilizer next to the plants – about one tablespoon per plant. Lightly mix the fertilizer into the soil and irrigate.

Collards can be grown in containers that are at least a foot deep. Sow several seeds and thin perhaps less aggressively than you would thin ground-planted seedlings, assuming you’re going for that bursting-at-the-seams look.

If you leave spring-planted greens in the ground too long, the plants may bolt and start producing flowers. The flowers are small and attract bees, but the plant’s leaves will take a bitter turn when it bolts.

If you’d like to collect seeds, stop watering after the plant bolts. The seed pods will turn brown and dry out. Crack one open and see if the seeds are black, a sign of harvest readiness. Be sure to pluck the pods before they split, spilling their seeds to the ground, and before the birds beat you to them!

Break open the pods and store the seeds in a paper envelope or bag in a cool, dry place. They should be viable for about four years.

Keep in mind that seeds from most hybrids won’t reproduce true to type. So you can still collect and plant the seeds, but they will not produce a harvest identical to that of the mother plant.

Growing Tips

- Make sure soil is rich in organic material.

- Give your greens plenty of water, at the base of plants, avoiding the leaves.

- Fertilize now and then, especially if you see yellowing leaves.

Cultivars to Select

There are a variety of different cultivars available for planting in your home vegetable garden.

Champion

An heirloom collard variety that seems to do well pretty much everywhere is ‘Champion.’ This is a high-yielding type that is resistant to many diseases and grows to 34 inches tall.

Find seeds for ‘Champion’ at Eden Brothers. You’ll be able to enjoy your harvest about 75 days after planting.

Georgia Southern

‘Georgia Southern’ is another heirloom type often grown in the South. This one is ready to harvest in about 80 days, and is slow to bolt.

Via Amazon, David’s Garden Seeds offers a packet of 200 seeds with an 80% germination rate.

Vates

Grown throughout the United States, ‘Vates’ was developed in Virginia during the Great Depression.

It produces long, wide, dark blue-green leaves in 68 to 75 days. You can get a one-ounce package of these seeds from Eden Brothers.

This type is also slow to bolt and grows to be about 32 inches tall.

Merritt

‘Merritt’ is a fun variety to consider. It is an open-pollinated hybrid of ‘Vates’ and ‘Georgia’ with a little kale DNA mixed in.

It was discovered at Merritt College in Oakland, California, and all subsequent seedlings can be traced to a single mother plant. It can grow to four to six feet tall.

Tiger

And finally, you might want to consider ‘Tiger,’ a hybrid that produces hardy, upright leaves 20-25 inches in height, that are ready to harvest in 55-60 days.

This variety has broad and thick blue-green leaves that regrow easily, with narrow stalks. Known for its exceptional flavor, Burpee rates this cultivar as “Best in Class.”

Find a package of 350 seeds, available from Burpee.

Want more options? Make sure to check out our supplemental guide, “7 of the Best Collard Greens Varieties to Grow at Home.”

Managing Pests and Disease

Unfortunately, collards are appealing not only to humans but also to a number of pests. They are also susceptible to fungal diseases.

Deer

Deer are known to enjoy munching on collard greens, and they’re smart enough to know to wait until after a frost or two, for the sweeter leaves.

If hungry deer are a big problem for you, you might want to read this article about building a deer fence next.

Insects

As members of the Brassica family, which includes cabbage and broccoli, collards are susceptible to the same pests that bother other family members. Many gardeners have luck with row covers to keep the plants from being bugged.

But if your plants have unwelcome snackers such as the following, we have some tips for you:

Aphids

Because, of course. Aphids are hungry, pear-shaped, soft-bodied pests that like to suck the fluids from the leaves of probably 10 billion plant species (alright, this is admittedly an exaggeration since there are about 391,000 plant species in the world, but you know what I’m getting at), and collard leaves are not immune.

Blast them off with water, or use an insecticidal soap to ward against them.

Cabbage Worms

Cabbage worms are any of several moth caterpillars that eat collards and other plants in the Brassica family. Cabbage loopers would fall in this category.

If you prefer these hungry little beasts not annihilate your collard crop, check out this article with plenty of advice and tips for getting rid of the voracious vermin.

Slugs

If you see shiny trails on the leaves of your collard plant, along with evidence of nibbling on the leaves’ outer edges, you may have a slug infestation.

You can learn how to keep vile, slimy slugs off your collards with this guide.

Beetles

A few types of beetles, including flea, blister, and white-fringed, can pester collards. You’ll see multiple little holes in the leaves, particularly in those of young plants.

Use insecticidal soap on these beetles, as well, or sprinkle diatomaceous earth around the growing area and on the plant’s leaves.

Harlequin Bugs

These colorful pests stuck fluids from plant parts, leaving behind little white dots, or stippling. As the plant becomes increasingly ill, it will wilt, turn brown, and die.

Insecticidal soap may be effective on harlequin bug nymphs, but as the insects mature, you may have to turn to spinosad, a natural pesticide that can be found online or at garden centers.

Nymphs are small, rounded, and black with green, red, or orange markings.

You may have luck with neem oil, or, of course, you can also pluck harlequin bugs off by hand. Because how fun does that sound?!

Thrips

Thrips are tiny, slim, winged insects that suck fluids from plant leaves. Yellow specks on leaves may be a symptom of a thrip infestation. You may also see black dots of frass – or thrip poop – on the leaves of your plants.

Use insecticidal soap, neem oil, or spinosad to control thrips.

Find more on identifying and combating thrips here.

Weevils

Weevils are another collard pest. They chew notches around the edges of leaves.

To treat, first sprinkle diatomaceous earth around the vegetable patch and on the leaves of the plants. Then, try insecticidal soap or neem oil; these are particularly effective on the larval form of the pest. You can also hand-pick the bugs.

Disease

Collard greens are susceptible to a number of fungal diseases.

Anthracnose

Anthracnose (Colletotrichum higginsianum), for example, presents as small gray or off-white spots on leaves.

Alternaria

Alternaria (Alternaria spp.) leaf spot produces brown-tan concentric spots with yellow edges on leaves; you may also see brown to black lesions with a black border on the plant’s roots.

Clubroot

Clubroot (Plasmodiophora brassicae) results in slow-growing, stunted plants. Leaves may be yellow and wilt during the day, reviving to a small degree during at night.

Downy mildew

Downy mildew (Peronospora parasitica) may be the problem if you see tan or yellow spots on the upper surface of leaves. This disease also produces fluffy gray or white mold on the underside of leaves. Downy mildew can also cause the leaves to fall off.

Treat these with a commercial fungicide, available online or at garden centers.

Bacterial Soft Rot

Bacterial soft rot can be caused by several types of bacteria, with Erwinia carotovora being among the chief culprits.

Plants affected by these bacteria turn soft and mushy, and you may see a slimy substance oozing from plant parts. You may also detect a foul scent emitting from affected plants, which must be uprooted and discarded.

Harvesting

You can begin harvesting collard leaves whenever they’re the size you want to eat them. Typically this is at around 40 days, but it can be as early as 28, or even younger as we mentioned above regarding thinning.

You can harvest the entire plant, or you can simply cut off outer leaves as needed, allowing the plant to continue growing.

If you’ve done a fall planting, be sure to let them endure a frost or two, for the best flavor.

Read more about harvesting collard greens here.

Preserving

If you’re harvesting in advance, you can store the leaves in a zippered bag in the crisper drawer of your refrigerator for about a week. Do not wash the greens before putting them in the bag, and squeeze out as much air as possible as you seal it.

Wash the greens just before you use them.

You can also freeze your greens. In this case, you do want to wash them very thoroughly before storing.

After washing, remove the tough center stem. To do this, experts recommend folding the leaf in half lengthwise, inward along the stem, grasping the leaf in one hand and and the stem in the other, and ripping up on the stem to tear it away.

You could also cut the stems away with a sharp knife, or kitchen scissors.

Boil the greens in water for 3-5 minutes; do not add seasoning to the pot. Immediately plunge the greens into ice water. Blanching helps to preserve the greens’ flavor, and it destroys the enzymes that cause leaves to lose their color.

Drain the greens thoroughly, blot them dry with paper towels, and then package them in a plastic storage container or zipper bag, removing as much air as possible.

They will store well in the freezer for about a year if prepped this way.

Recipes and Cooking Ideas

Smaller leaves can be eaten raw, added to salads or used as a low-carb wrap alternative.

Collards are a cornerstone of traditional American soul food, and every Southern cook has his or her own secret recipe. The traditional method of cooking these greens involves starting by boiling down ham hocks with salt until the meat is falling off the bone.

The greens are added to the pot and cooked for 45 minutes or more, depending on how tender the leaves are, and then drained, chopped, and salted. Some cooks add “toppings” such as onions, vinegar, small whole tomatoes, or hot pepper sauce.

A tip favored by many Southern cooks is to save the cooking water, which is packed with nutrition and flavor, to use the base for a sauce or soup. Or leave the greens “soupy” and dip cornbread in the broth,

In the South is called pot liquor or sometimes “potlikker.” Some aficionados just drink potlikker as a nutritional beverage.

You might also like to try the recipe for creamed collard greens, from our sister site, Foodal. These flavorful greens are a tasty spin on creamed spinach.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Annual | Water Needs: | 1.5-2 inches per week |

| Native to: | Mediterranean | Maintenance: | Low, keep an eye out for pests |

| Hardiness (USDA Zone): | 8-10, some varieties up to zone 6 | Soil Type: | Fertile |

| Season: | Spring or fall | Soil pH: | 6.0-7.5 |

| Exposure: | Full sun | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Time to Maturity: | 80 days | Companion Planting: | Scented marigolds, mint |

| Spacing: | 12-18 inches | Avoid Planting With: | Rue, strawberries |

| Planting Depth: | 1/8 inch (seeds) | Order: | Brassicales |

| Height: | 2-3 feet | Family: | Brassicaceae |

| Spread: | 12-18 inches | Genus: | Brassica |

| Tolerance: | Frost | Species: | B. oleracea var. acephala |

| Common Pests: | Aphids, beetles (esp. flea, blister, white-fringed), cabbage worms, deer, harlequin bugs, thrips, weevils | Common Disease: | Alternaria leaf spot, anthracnose, bacterial soft rot, clubroot, downy mildew |

This Plant’s Got Soul

Ready to add this nutritious leafy green to your vegetable patch? Even if you don’t live in the South? If you are, be sure to give them fertile soil and a decent amount of water.

Watch for pests, perhaps implementing a row cover to help ward off bugs.

Harvest as needed – maybe cook up at least one mess of greens in the traditional style, and then branch out into other preparations.

Have you grown collards? Are they a part of your cultural heritage? Share your thoughts in the comments section below!

If you’d like to grow a variety of greens, check out these articles:

- How to Grow Kale

- Leafy Greens For Salads And Sautees: How To Grow Spinach

- How To Plant And Grow Swiss Chard

Ask the Experts, LLC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. See our TOS for more details. Product photos courtesy of David’s Garden Seeds, Project Tree Collard, Eden Brothers Nursery, and Burpee. Uncredited photos: Shutterstock. Additional writing and editing by Clare Groom and Allison Sidhu.

African Americans absolutely are due credit for the widespread popularity of collard greens in Southern cuisine! I don’t believe Gretchen’s statements about the history of cultivation of this plant were in any way meant to obscure or deny that fact, and I apologize for any offense this section of the article that you’ve referenced may have caused. Instead, Gretchen’s description at the beginning of the history section of this article was meant to explain earlier origins of the plant, dating back to 500 BC and beyond. The exact origin of collards is unknown, and as far as botanical experts can… Read more »

Excellent article. I don’t/can’t find articles as detailed as this one is about Collard Greens. Much appreciated!

Born in the South and returning each year, I know Collard Greens were common and definitely a staple in my family’s gardens. Generations of Southern, African American culture. This article’s inclusion of history was really great. Finally, after all these years wanting to, I’m beginning gardening. Collard Greens definitely included and the reality feels a bit inspiring with the mindfulness of my family’s history of inclusion.

Thanks so much for getting in touch, Jacqueline! I’m so glad our article helped to inspire you. Wishing you all the best with your new garden. Please reach out if you ever have any questions!