Zea mays var. saccharata or Z. mays var. rugosa

The first year I moved to Alaska, I threw some sweet corn seeds down in my flower bed halfway through the summer, gave them some water, and blew them a kiss goodbye.

Okay, not really (the kiss part). The seeds germinated and the seedlings grew a few inches – and then died. Of course.

Because chilly September came when they were still young, and then October hustled in with its first snowfall.

I wised up after that waste of seeds and garden space. Since then, my maize-growing knowledge has expanded and every year I grow tall, fluttery-green stalks in my garden.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

Honestly, the idea of growing sweet corn can be daunting. How tall does it grow? Will it create shade over your entire garden? How is it pollinated? When do you harvest it?

If you’ve never grown sweet corn (Zea mays var. saccharata or Z. mays var. rugosa, or sometimes Zea mays convar. saccharata var. rugosa) before, or if you need help with the maize you’re growing in your garden, I’ve got you covered.

Ready to grow your own crisp, tasty sweet corn?

What You’ll Learn

Before we get growing, I’ll share some surprising secrets about the history and nature of this widely consumed grain.

The sweet variety is mostly eaten as a vegetable, which is fitting; maize is rich in fiber, folate, phosphorus, vitamin C, thiamin, and magnesium.

Cultivation and History

If it weren’t for humans, corn as we know it today would not exist.

While it’s a whole grain from the grass family, Poaceae, Z. mays isn’t found anywhere in the wild. Nine thousand years ago, Mesoamericans created corn out of almost nothing.

And by “nothing” I mean this unassuming little grass, teosinte (Z. mexicana).

With just a few edible kernels in each tiny ear, teosinte isn’t a food crop.

But early Mesoamerican cultivators caught on to a genetic mutation that removed teosinte’s hard outer casing, which made the grain inedible.

They carefully saved and planted the special kernels in order to create the maize we know today.

That was at least 5,000 to 7,000 years ago, as evidenced by the 5,000-year-old cob of maize found in the Guilá Naquitz Cave in Oaxaca, Mexico in the 1950s, and carbon-dated in the early 2000s.

For millennia, indigenous peoples throughout the Americas grew maize.

The exact origins of sweet corn are unclear, but it’s generally understood by scientists that the sweet variety may have been discovered by accident, when a recessive mutation of genes occurred in maize and altered the sugar and starch levels in the plant.

People of the Iroquois Nation cultivated this type of corn into a cultivar they named ‘Papoon.’

During the American Revolutionary War, Lieutenant Richard Bagnal of the Poor’s Brigade stole the cultivar from the Haudenosaunee.

Over the years, settlers and scientists cultivated ‘Papoon’ into what’s widely considered the “original” sweet corn, or sugary-1 (SU).

We can thank John Laughnan, a botany professor and corn geneticist at the University of Illinois, for developing supersweet corn in the 1950s.

Laughnan found that the SH2 gene in sweet corn produced kernels with up to four times more sugar and less starch than other types of corn, and developed supersweet corn from there.

In the 1980s, another University of Illinois professor, Dusty Rhodes, discovered the more tender but less sweet sugary enhanced (SE) corn.

There are four main types of sweet corn grown and consumed today: SU, SE, SH2, and SYN.

Here’s a quick breakdown of the differences between the four:

Standard (SU)

The standard sugary corn, or SU, is well known for its sweet, creamy texture. It should be eaten within a week after harvest for the best taste.

The SU type contains more sugar and less starch than field corn, which is primarily used for grain and harvested when the kernels are dry.

The high levels of sugars in SU and other sweet varieties are the result of a natural genetic mutation that controls the conversion of sugar to starch in the plant, making it sweet during the milk stage prior to the kernel’s full maturation.

Sugary Enhanced (SE)

SE is an enhanced version of SU, with a higher sugar content than standard sweet corn but less sugar than supersweet (SH2).

A gene in the SE type causes an increased amount of sugar in the kernels, which also leads to kernels that are more tender.

SE is popular because it retains its taste and texture much longer than standard SU types after harvest.

Supersweet (SH2)

SH2 is – that’s right, you guessed it – super sweet.

In fact, it has four to 10 times the sugar content of varieties of the SU type. SH2 has a very low starch content when the kernels have fully matured.

Synergistic (SYN)

This fascinating type of sweet corn, abbreviated SYN, is a hybrid of 25 percent SH2 and 75 percent SE, which makes for crunchy yet tender kernels that hold their flavor well in storage.

Sweet Corn Propagation

There are two ways to propagate sweet maize: from seed, or from transplants, which you can find in some local nurseries.

From Seed

Before you plant maize, it’s important to know the right time and place for planting.

Seedlings actually transplant pretty well, so you can start seeds indoors or outdoors and grow them in USDA Hardiness Zones 3 to 11

Outdoor Sowing

First, the weather is an important consideration. Z. mays is not tolerant of cold, so wait until two to three weeks after the last frost date in your area to plant your seeds.

Make sure your average temperatures in early spring aren’t continuously below 60°F if you choose this method, since you’ll find it challenging to successfully establish seeds in cold soil.

The soil temperature should be no lower than 50°F for optimal germination.

To help improve the germination rate of your seeds and to speed germination along, soak them overnight in tepid water before planting.

Pick a planting location that gets at least six to eight hours of sunlight per day. The soil should be rich, so amend your soil with well-rotted manure or compost before planting.

Sowing is easy. To sow seeds, dig a hole about one inch deep and place two to three seeds inside. Cover them lightly with dirt and water thoroughly.

You’ll want to space the holes about seven to 12 inches apart. Arrange your seeds in a block pattern – a four-foot-by-eight-foot square or something similar, depending on the size of your total planting area – instead of in rows.

Each individual cob should be seven to 12 inches apart from the others within the square.

This is because Z. mays is wind-pollinated. Planting your crop in a block makes it more likely that pollen from the tassels will drop on surrounding silks instead of on bare earth (or your carrots, peas, or whatever else you planted next door).

This cereal crop is a heavy feeder and each plant will need some elbow room. When planting a block of rows, space each block about one to two feet apart.

Small gardens can successfully yield 15 to 20 plants in a four-by-six-foot bed with proper spacing.

Keep the soil moist, but not waterlogged, until germination, which can take anywhere from 10 days to three weeks

Once each plant has two sets of leaves, pinch off the smaller one or two seedlings every seven to 12 inches to allow the strongest one to thrive.

Indoor Sowing

To start seeds indoors, do so about two weeks before your average last frost date.

Fill a seed tray with potting soil and make a one-inch-deep hole in each cell. Drop two to three seeds inside, cover lightly with soil, and keep evenly moist.

Once germination occurs, set the tray in a sunny windowsill that receives at least six to eight hours of light a day or more.

If you don’t have much sun, position a grow light an inch away from the seedlings, adjusting it as the plants grow.

Once each plant has two sets of true leaves, pinch off all but one seedling per cell.

From a Transplant

Sometimes, you’ll find seedlings at a local nursery. Or maybe you’ve successfully sown seeds indoors and want to transplant them to the outdoor garden.

Here’s how to do it:

Make sure the area you’re transplanting to receives at least six to eight hours of full sunlight a day. The soil should be organically rich, so amend with well-rotted manure or compost.

Dig holes about seven to 12 inches apart. I wanted to fit more plants in my garden, so mine are more like seven to eight inches apart.

The holes should be the same size as the root ball you’ll be transplanting.

Set the root ball inside the hole and backfill with soil, taking care not to cover the stem. Water thoroughly, add a layer of mulch to keep moisture in and weeds out, and watch your sweet corn thrive!

How to Grow Sweet Corn

Sweet maize prefers organically rich, loose, well-draining soil with a pH of 5.5 to 7.0.

If you want to plant several varieties of sweet corn, maximize the space you have in your yard.

Unless they are the same variety or you’ve staggered out your plantings, each plot should be spaced at least 100 yards apart to avoid any unwanted cross-pollination.

Corn is wind-pollinated; the tassels are the male flowers of the plant, and the silks and ears are female. Wind blows pollen off the tassels and onto the silks.

Each strand of a silk is connected to an individual floret on the ear. Pollen from the tassel travels down the strand and pollinates each floret, giving it the reproductive cells to become a tasty kernel.

If you plant multiple varieties together, various genetic traits of each variety will mix.

This sometimes produces unfavorable results. SH2 kernels, for example, must not be grown near other sweet varieties because the cross-pollination would result in a suppression of the gene that makes it supersweet, essentially turning it into field corn.

Even worse is to plant sweet corn near something like popcorn. I learned this lesson the hard way by literally planting my sweet maize and popcorn side by side.

When I realized that the popcorn tassels would pollinate the sweet corn silks, which would result in starchy, chewy kernels (yes, I’d planted them at the same time – I know, I know!) I had to transplant the popcorn out of the garden.

I caught my mistake when the plants were still young, which made transplanting easy.

I simply used a trowel, carefully dug up the popcorn, and replanted it in a large, deep, square container.

Since I was taking the corn away from the enclosed garden, I sprayed it with Plantskydd to protect it from moose.

The stalks are tall, green, and happy in their container that’s located on the opposite end of my property from the raised bed garden.

Of course, the much easier solution to avoid cross-pollinating is to plant different varieties far from each other to begin with, or to stick with one variety.

As far as fertilizing goes, make sure your sweet corn gets regular doses of nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium with a balanced NPK fertilizer, such as 10-10-10.

Apply it according to package instructions, every two to three weeks.

You could also add blood meal and bone meal, according to the instructions on the packages, for a combination of nitrogen and phosphorus.

If your plants start to turn a light yellow instead of a rich, dark green, then they are telling you something: Feed me! Yellowing of leaves is a sure sign that the plant needs more nitrogen.

And if you don’t give them enough phosphorus, the leaves may start to turn purple at the edges.

This happened to both varieties I’m growing.

I added bone meal to the soil, which is high in phosphorus, by sprinkling it on top and working it in a couple inches deep.

Within a week, new green leaves were emerging.

As for moisture, you’ll want to give each plant about one inch of water every week. Drip irrigation works well. Or, water at the base of each plant.

The final thing to keep in mind is that you may need to “hill” the corn to support the tall stalks.

To do this, simply mound soil about two to three inches high around the base to help keep each stalk straight.

You might want to bring in some rich gardening soil from your local gardening store to give the plants a nice nutrient boost as well.

Repeat this process as necessary, usually every two to three weeks.

As you approach harvest time, your plants will be heavy and susceptible to heavy winds.

Drive a simple wooden stake down into the earth in between two plants, and use twine or stretch tie to secure two stalks to each stake.

This will help them stand tall, and prevent them from toppling over under the weight of the developing ears.

Growing Tips

- Space different varieties at least 100 yards apart to avoid cross-pollination.

- Fertilize with a balanced product, such as 10-10-10 NPK, every two to three weeks.

- Provide plants with one inch of water per week.

- Hill every two to three weeks to provide support.

- Consider hand pollinating for low density stands.

Sweet Corn Cultivars to Select

In this section, I’ll share my favorite SU, SH2, SE, and SYN varieties. For even more options, check out our roundup of the 11 best varieties to plant in your garden.

Bodacious, a Full-Bodied SE

While it takes up to 90 days to mature, ‘Bodacious’ is worth the wait. This SE variety grows eight-inch cobs with 18 rows of sweet, milky kernels.

Their delicious flavor lasts for 10 days post harvest, so if you plant a new block of seeds every two weeks, you’ll have enough corn for all of your late-summer and early fall cookouts.

Get your ‘Bodacious’ seeds in a variety of packet sizes at Eden Brothers.

Early Sunglow Hybrid, A Cool-Weather SU

Suitable for Zones 3 to 11, ‘Early Sunglow Hybrid’ is an excellent choice for cold-weather gardeners. Plus, it matures in as little as 62 days. That’s fast for maize!

With a golden color and a petite, four-foot stature at maturity, this SU cultivar produces six to seven-inch ears for your enjoyment.

Eat within two days after harvest for the sweetest flavor.

Find seeds in a variety of packet sizes available at True Leaf Market.

Honey Select Hybrid, A Delightful SYN

This delicious mix of tender and crunchy delivers eight- to nine-inch cobs about 80 days after germination.

Stalks grow to five or six feet, so while they’re tall, they’re not enormous compared to other varieties.

With indoor sowing, ‘Honey Select Hybrid’ grows well in Zones 4 to 11.

Find seeds in a variety of packet sizes available at True Leaf Market.

Illini Xtra Sweet Hybrid, A Supersweet SH2

This hybrid delivers on sugar content, and cobs stay sweet for days, giving you plenty of time to enjoy them after harvest.

‘Illini Xtra Sweet Hybrid’ grows six feet tall at maturity, and delivers eight-inch ears in 85 days. This cultivar grows best in Zones 4 to 11.

Find packets of 200 or 800 seeds at Burpee.

Managing Pests and Disease

Sweet corn is susceptible to several pests and diseases. By checking on your crop each day, however, you can prevent many problems.

Here are a few prevalent pests and diseases to watch out for.

Insects

Three of the most bothersome bugs for sweet corn are aphids, cutworms, and the European corn borer.

Aphids

Blue-green corn leaf aphids (Rhopalosiphum maidis) and greenish-yellow green peach aphids (Myzus persicae) will stunt plant growth when they suck sap from leaves, and leave a sticky substance called honeydew in their wake, which can then develop sooty mold.

Since aphids also love weeds, keeping your garden well-weeded is important.

To get rid of aphids, use a strong blast of water from the hose to knock them off and then spray neem oil on each plant to discourage re-infestations.

Check out this guide to learn more about managing aphids in your garden.

Cutworms

These gray-brown worms are essentially seedling decapitators, cutting seedlings away from their lifeblood: the root systems of your young plants.

Not only that, but cutworms – most commonly the Agrotis ipsilon, Peridroma saucia, and Feltia ducens species – often proudly curl up next to their fallen prey, like the rascal next to the sad, dead lettuce plant pictured above.

To keep these pests away, make a tinfoil necklace for each plant and place it around the stem.

Check the collar every day to make sure there isn’t any sign of cutworms, as well as to make sure the stem isn’t rotting.

Remove the collar before watering and replace after an hour or so to give the plant time to breathe.

Once the seedlings grow into strong young plants with thick stalks, remove the collars.

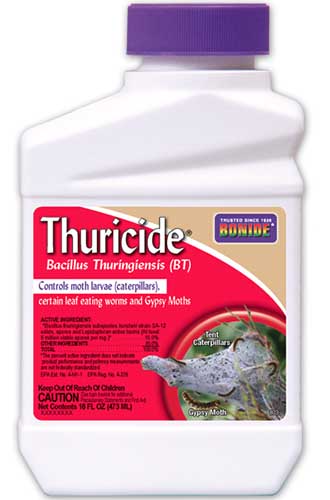

Monterey Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) Spray

Spray existing worms with Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) spray, like this one from Arbico Organics.

You can learn more about Bacillus thuringiensis in this guide or read more about controlling cutworms here.

European Corn Borer

These nasty whitish caterpillars (Ostrinia nubilalis) attack tassels, often snapping them off the stalks.

They also hollow out sweet corn stalks by eating through stems and munching through the cob shafts, causing them to fall off the mother stalk. And they like to nibble on developing kernels as well.

In short, they’re bad news for your garden. They often leave a pile of frass, aka poop, behind when they drill into a stalk, so keep your eye out for any strange masses under the leaves. The frass looks a bit like sawdust.

To control infestations, treat with thuricide according to package instructions.

Try this product from Arbico Organics.

Disease

All sorts of maladies can infect your sweet maize. Here are a few top annoyances.

Anthracnose

Caused by the fungus Colletotrichum graminicola, anthracnose presents as tan, brown, or even necrotic lesions on leaves. Left untreated, stalks can eventually rot, killing the entire plant.

This fungus thrives in hot, humid weather, so maintaining adequate airflow between your stalks is important.

Remembering to water at the base of each plant (instead of hosing them down from above) can also help.

Manage an existing anthracnose infection as early as possible in order to enable your plants to keep growing and producing ears.

Bonide Revitalize Biofungicide

To treat, spray plants with Bonide Revitalize Bacillus amyloliquefaciens Biofungicide, available from Arbico Organics.

Common Rust

Easily identified by its, well, rusty spots on the leaves, common rust is caused by the fungus Puccinia sorghi.

While it can affect all types of corn, it especially adores sweet corn and is sometimes called “common rust of maize.”

A copper fungicide spray, like this one from Arbico Organics, can treat the disease.

Gray Leaf Spot

Caused by the fungus Cercospora zeae-maydis, gray leaf spot appears as tan lesions on the leaves about two weeks before the corn produces tassels.

If untreated, the lesions will turn brown, grow larger, and merge, killing entire leaves.

This eco-friendly spray from Arbico Organics can help control outbreaks.

Harvesting and Preserving Sweet Corn

For tasty-fresh corn, harvest at the milk stage. This occurs 18 to 20 days after tasseling. The silks will be a dried-out brown, and the ear will feel plump and firm when you wrap your hand around it.

To harvest, gently grasp an ear with your hand and bend or twist downward. Wrap ears in damp paper towels to preserve their flavor in storage in the refrigerator, and wait to husk until you’re ready to use them.

Eat SU corn as soon as possible for the best flavor. SE, SH2, and SHY types hold up better in storage, giving you more time to eat them fresh or preserve them.

Kernels may also be blanched and then frozen and stored in the freezer for up to 12 months.

That’s the short version.

For a complete guide to harvesting and preserving sweet maize, check out our guide to harvesting corn.

Recipes and Cooking Ideas

There’s an endless array of delicious dishes you can make with your maize.

My favorite thing to do is grill it, slather it with butter, add a sprinkle of salt, and cut it off the cob to eat.

I don’t like getting it stuck in my teeth, so I eat it like a little kid. And it’s good.

My second-favorite way to eat it is in the form of these divine sweet corn fritters from our sister site, Foodal.

I also love this roasted sweet potato, corn, and black bean salad with spicy miso dressing for a perfectly light and zingy summertime dish. You can find the recipe for this dish on Foodal as well.

Whichever recipe you choose to use or dream up yourself, it’s sure to taste a hundred times better when you make it with your own homegrown sweet corn.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Annual cereal grass | Maintenance: | Moderate |

| Native to: | Mesoamerica/North America | Tolerance: | Mild heat |

| Hardiness (USDA Zone): | 3-11 | Soil Type: | Rich and loose |

| Season: | Summer | Soil pH: | 5.5-7.0 |

| Exposure: | Full sun | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Time to Maturity: | 60-90 days | Companion Planting: | Beans, pumpkins and other types of winter squash, sunflowers |

| Spacing: | 7-12 inches | Avoid Planting With: | Celery, tomatoes |

| Planting Depth: | 1 inch (seeds) | Family: | Poaceae |

| Height: | 4-7 feet | Genus: | Zea |

| Spread: | 6-8 inches | Species: | mays |

| Water Needs: | Moderate | Varieties: | saccharata or rugosa |

| Common Pests: | Aphids, cutworms, European corn borers | Common Diseases: | Anthracnose, common rust, gray leaf spot |

Everything Corny and Wonderful

It’s truly thrilling to watch your tiny seedlings grow tall and strong. There’s nothing like seeing those tassels and silks form and then watching ears develop, knowing you’re in for a tasty treat.

What do you love most about growing sweet maize? Let us know in the comments below!

And for more information about growing corn in your garden, check out these guides next:

I’m growing a freaky variety and playing a trick on a friend, thinking it’s sweet yellow corn when it’s actually a dark multi-colour corn called glass gem… I need to know how long it takes cobs to mature after pollination, and I’m pretty desperate for an answer as he is talking about opening one for a look inside and my trick will be ruined… please help! (lol)

Also, is 13 cobs on 1 plant good or bad? should I pluck a few of them off to get better quality but fewer cobs?

Apologies for the very delayed reply, Dave- I’m not sure how we missed this question when it was posted! Was your friend surprised? Most types of corn require about 18-20 days to mature after the tassel stage, with about 110 days total for ‘Glass Gem’ from planting time. Thirteen cobs does sound like quite a lot for one stalk. Most types will produce 1-4 ears per stalk, and this depends in part on spacing of the plants and pollination rates as well. Since corn is a heavy feeder that also requires a lot of water, reducing the number of cobs… Read more »

Yes

I just started to grow it and I need tips for next year.

My seeds flew of the corn before the ears were there.

Just to be clear, corn and other fruits and seed pods don’t change characteristics from cross pollination. It’s the next generation of plants from those seeds which will have different characteristics. In sum, unless you’re intending on drying and replanting kernels that have been cross pollinated, it doesn’t matter if you’ve grown different varieties next to each other.

Hi Michael! Thank you for your comment. It’s certainly true that in most cases, cross-pollination doesn’t matter unless you’re saving seeds for planting. But with corn, it does because you are eating the seeds (the kernels). If sweet corn kernel ovaries are pollinated by nearby popcorn tassels, you’ll get cross-pollinated kernels on the sweet corn — and they’ll be tough like popcorn kernels. Hope that makes sense!

Awesome article. Seeing my first ever corn plants grow is exciting

I can see tassels now. It’s been 60 days since we planted, about 20 plants in my garden bed.

What next? 🙂

You should start seeing the stalks swell into ears soon, with silks poking out! My sweet corn tasseled about 1.5 weeks before ears appeared this year, but it was so exciting when those ears finally came. Make sure that you get all the ears pollinated — I like to do it by hand by brushing tassels (that I’ve broken off) all over the silks.

Once the corn is ready to harvest, get the water boiling go pick your corn then drop it in the water for 3 minutes. It’s amazing!!

Susan, I could not agree more! Thanks for your comments.