Most home gardeners learn quickly that there are some crops that need protection and rescue from a variety of common pests.

Hornworms are going to munch on your tomatoes; slugs are going to chew your lettuce down to a nub; and aphids – well, aphids may make an appearance on absolutely anything.

And indeed, cabbage is one of the plants you’ll want to take extra care to supervise, as there is a long list of potential pests, some of which can be devastating if left to do their worst.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

There are numerous varieties of cabbage, and all of which belong to the Brassica genus which includes broccoli, cauliflower, brussels sprouts, and kale.

Pests that enjoy eating your cabbage also present a danger to your other brassica crops, so be wary – if they’re munching on one crop, they may be munching on all of them!

What are the warning signs, and how are you going to deal with the pests present on your cabbage plants? Let’s make a plan!

What You’ll Learn

Planning Ahead

Humans have been cultivating agricultural crops for centuries, and in that time, they’ve developed creative, experientially-driven methods to deal with garden pests and crop damage from hungry wildlife.

Even though it’s a pain to see your crops being decimated after all of your hard work, take comfort in the fact that you have the advantage of all of those years of scientific research and testing, coupled with trial and error, to help you reverse course on pest and animal crop damage.

It’ll just take a little education and some extra time to put those methods into play.

Preventative measures are often the easiest to achieve to protect your crops from damage by infestation. Planning ahead saves you some of that time and effort later on.

While you’re planning your garden prior to the beginning of the gardening season, consider adding some additional plants of each variety to your list.

More plants are likely to produce a higher crop yield even when there is some damage from pests. Just be sure to keep the number manageable for your skill level and your available time and space.

Speaking of which, be sure to provide adequate plant spacing, as a little extra room between leaves can be beneficial in preventing the spread of both infestation and disease – which can occur hand in hand.

Make a note of the types of pests you’ve observed in the garden in prior seasons and where infestations occurred.

Learn what material in your garden was harboring those insects and remove what you can, such as debris, leaves, or other hiding places. A garden journal can be an indispensable record-keeping tool.

Your garden plan should allow for crop rotation – avoid planting the same crop in the same part of the garden year after year.

This can help to reduce or remove access from insects that may have been present on last year’s plants or that have remained in the soil.

If you’re able to fence your garden or plant some crops in containers, and out of reach of pests and herbivorous animals, that could save you from some grief later on.

Covering crops with row covers or mesh can also create a barrier, but be aware that covers may not prevent access for soil-borne insects.

If you’re gardening in a place that allows for winter planting, this is the perfect time to grow brassicas, as they’re typically very cold hardy and some varieties are bred specifically to withstand colder temperatures.

Winter planting, especially in cold frames, can prevent infestation and crop loss to hungry animals.

Finally, if you’ve had some previous pest issues in the garden and you want to bolster your defenses against reinfestation, encourage or introduce beneficial insects such as ladybugs, praying mantises, or green lacewing flies at the beginning of the gardening season.

They’ll make short work of numerous types of problematic pests in your cabbage patch.

Common Cabbage Pests

In our guide to growing cabbage, we cover how to plant and care for this cool weather crop. However, even with the best planning and adequate supervision, pests can still appear in your garden.

Once they are present, do your best to act before they have the opportunity to cause significant damage.

And again – take note of areas in the garden where infestation has occurred to help you plan for next season’s planting as well, as some pests can come back year after year.

Any time when pests invade, give careful consideration to all methods of treatment, as application of pesticides can sometimes cause more harm than good.

Many pesticides affect not only the pest insect, but beneficial insects as well.

They can become part of the environment, and can often harm animals that consume affected insects, rodents, and other wildlife. Other mechanical or environmental control methods are almost always the better choice.

Grab a cup of coffee and settle in – we’ve got a lot to talk about.

Hopefully, you’re looking for information ahead of planting season rather than in response to finding damaged crops in your garden.

Either way, the list of cabbage pests is long. But fortunately, so is the list of potential solutions to an infestation.

Aphids

What pest-focused article would be complete without a mention of the aphid?

They’re known the world over for being the least picky garden pests, while also being capable of some serious damage if left to breed at will.

There are thousands of species of aphid, and they range in color from nearly translucent white to bright scarlet red.

You’ll most commonly see gray-green cabbage aphids (Brevicoryne brassicae), on your cabbage and other brassicas.

These pests are tiny – about one-eighth of an inch long – with a dusty-looking white coating on their bodies that can appear ash-like. This coating can be left on the surface of leaves as well.

They can live through the winter in protected structures, and produce eggs without mating, so if you find one, you may have hundreds soon.

Because this species targets brassicas, they can sometimes be active in temperatures as low as 50°F.

If you’ve decided to plant in fall or winter to attempt to avoid infestation, you may still find you’re dealing with aphids until temperatures dip below 50°F.

When aphids are present, you’ll notice yellowing and curling leaves, and stunted growth. This is because the insects feed by piercing plants with their mouthparts and sucking out the fluids from inside.

A large enough infestation can be deadly for crops, so it’s important to look for these insects frequently, and watch for signs that they’re in the garden.

Pay extra attention to any ants that you may see traversing leaves of the plants in your garden, as they may be visiting a colony of aphids – the two have a symbiotic relationship.

Aphids can be dealt with by smashing them with gloved fingers, applying neem oil or insecticidal soap, releasing and encouraging beneficial predatory insects, and in several other ways.

Neem oil concentrate is available from Arbico Organics.

See our guide to dealing with aphids for more information.

Cabbage Maggots

Sometimes referred to as cabbage root maggots, these are the larvae of a small species of fly by the same name, or Delia radicum. These flies are between five and seven millimeters long, with gray to brown hunched backs.

Adult flies lay eggs on the stems of brassicas, such as cabbage and broccoli, near the surface of the soil.

Cool temperatures and moist soil incubate the eggs until they hatch, which can occur any time when conditions are favorable, and laying cycles may occur three to four times per year.

You’ll most typically see cabbage maggots attacking crops in early to late spring or early fall, when temperatures are still cool or are beginning to drop, as temperatures over about 95°F can kill eggs and larvae.

The maggots are only a few centimeters long, and white to pale yellow in color.

Those that attack brassicas will do so in great numbers, munching away at the roots of the plant under the soil, where you may not notice them until they’ve successfully decimated the entire root system.

Signs of the presence of these pests include yellow or purple leaf discoloration or plant dieback, wilting that leads to entire plants collapsing or being easily pulled from the soil, and tunnels appearing in the stems near the soil level.

When the maggots are ready to pupate, they’ll do so in the soil, overwintering near plant stems and emerging as adults in the spring.

Learn more about how to manage cabbage maggots in our guide.

Caterpillars

There are a number of different types of caterpillars that will feast upon your cabbage, and often, other brassicas that are planted in your garden as well.

Caterpillars are the larvae of butterflies and moths. A small number of any of these can cause some annoying damage, and a large number can absolutely decimate your crops.

Dealing with infestation of any of these can be a challenge with some of these species because several can lay eggs in more than one cycle throughout their active breeding seasons.

All of these species can be impeded from causing crop damage by introducing or attracting beneficial predatory insects into the garden.

You can introduce them in early spring when temperatures are suitable, and again in summer or early fall.

Traps are helpful in reducing the number of adult moths, as well as beetles and flies, that may be dwelling in your garden.

Arbico Organics carries pheromone traps and sticky traps for a variety of garden pests, designed to be outfitted with pheromone lures for moths.

Mechanical removal is helpful in dealing with infestation most of the time with caterpillars, as some can be seen easily after the first few days post-emergence.

These can be plucked off of plants and dropped into a bucket of soapy water, or removed or trapped and left out in a shallow container for the birds.

Don’t underestimate how much birds can assist in pest control either – if your plants are left in the open, as opposed to being under row covers or behind mesh barriers, and they have easy access, they can make short work and a hearty meal of the bugs that are bugging you.

Removing debris and rotting material from the garden is another important way to combat infestation, as you’ll notice that several species pupate in debris, and reducing hiding places can aid in reducing their numbers as well.

While pesticides are available for eradicating some of these nuisance insects, use caution in applying them to your garden, as they can not only become part of the plants that you’ll later be consuming, but part of the soil as well, where they can build up and cause harm to other species of insects and animals.

Bacillus thurengiensis v. kurstaki (Btk) is an effective biological control against caterpillars. This is a soil-borne bacterium that when ingested by the caterpillar, will release a toxin that will paralyze the digestive system.

It is best applied as soon as possible after hatching, and repeat applications may be required.

You can find Btk available from Arbico Organics as Bonide Thuricide.

Some of these pests can bear a strong resemblance to one another, and they can generally be treated in the same way, but there are some differences amongst them.

Let’s take a closer look.

Armyworms

As the name suggests, armyworms can appear on your cabbage, and many other plants in your garden, in a “small army.” In spite of their common name, they are not true worms, but caterpillars.

They feast upon the plants until they’re ready to pupate in the ground, emerging as adult armyworm moths after one to two weeks, who then go on to lay more eggs on your plants.

There are several species of armyworm moths, most belonging to the genus Spodoptera in the family Noctuidae. The adult moths are gray to brown in color, with white or cream-colored underwings.

Fall armyworm (S. frugiperda) moths typically appear in the garden in late summer through fall, while true armyworm moths (Mythimna unipuncta) generally appear through spring and summer.

The larvae of these species can range in color from brown to gray, with two distinctive stripes on either side of their bodies that can be yellow, orange, or white.

The larvae hatch from eggs laid on the undersides of leaves, and after eating their fill, they drop off to pupate in the soil.

Eggs can be laid throughout the spring and summer, so it can be a seemingly never-ending battle to deal with these pests.

Signs of armyworms include “skeletonizing,” or chewing of plant leaves between ribs and veins, and sometimes holes in forming cabbage heads.

Cabbage Loopers

It can be difficult to tell the difference between the cabbage looper and the cabbage worm described below. Cabbage loopers are greener in color, rather than yellow-tinged as with cabbage worms.

Cabbage loopers are caterpillars that have no legs in the center of their bodies.

They walk by “inching,” or pulling the rear section of their bodies forward. They range in size from less than a quarter-inch at hatching time to well over an inch long in final length prior to pupating.

These are cabbage looper moths, Trichoplusia ni, in their larval stage, and they can be extremely destructive.

Just as with armyworms, eggs are laid on the undersides of leaves, but also sometimes on the upper surfaces, and from the moment the larvae hatch, they will consume as much as possible.

Eggs are laid and hatch in the spring and summer, and can be laid in more than one cycle per year, so you may observe varying sizes of caterpillars on your plants. The adult moths are generally active in the evening and at night.

You can observe cabbage loopers resting in leaf margins and along the ribs of brassicas where their plump, green bodies often blend in well and may go unnoticed.

After they’ve had their fill, they pupate in white cocoons on dying plants and debris, and overwinter to emerge as adults in the spring.

Signs of the presence of cabbage loopers may include adult moths landing on plants; chewed holes in leaves and along leaf margins; frass, or droppings, on leaf surfaces; and die-off of outer cabbage leaves.

Be sure to check all brassicas planted in the garden when they are found.

Learn more about how to deal with cabbage loopers in our guide.

Cabbage Webworms

Webworms may bear a resemblance to armyworms at some stages, or instars, throughout the larval period.

They tend to be about the same size, between one-quarter and one inch long, and have a somewhat similar striped pattern.

The main visual difference is that the webworm has four brown stripes instead of two, and a black head.

Cabbage webworms are the larvae of Hellula rogitalis, or the cabbage webworm moth.

This brown moth with patterned upper wings and gray to light brown underwings prefers to lay eggs in conditions that are also favorable to several other pests, including aphids and diamondback moths – a tag team which can worsen defoliation and crop damage.

Throughout gardens in much of the southern and coastal United States, the moths can be found fluttering in short spurts along the ground in search of cruciferous crops.

In the late summer and fall, they’ll lay eggs on outer leaves that will hatch within two days to a week, depending on the temperature, and the feast will begin.

You can find cabbage webworm larvae on parts of cabbage and other brassica plants where they have caused obvious damage, such as chewed holes, discoloring, and skeletonizing. Stunted growth is also common in young plants.

You’ll notice some brown, dry-looking portions along leaf margins, or along the midribs, and it’s here that you’ll find the larvae tucked inside woven, web-like “pockets.”

This species will also chew through plant buds and stems, and can cause leaves to break and collapse. They sometimes pull leaves in on themselves, wrapping up safely inside a cocoon-like structure of webbing inside the leaf fold.

Larvae will drop off onto debris on the ground when they reach the pupa stage, burrowing into the soil where they’ll cocoon for one to three weeks. They then emerge to begin the adult phase of their life cycle.

Cutworms

A lot of gardeners refer to many different types of caterpillars collectively as “cutworms,” but these are actually several separate species.

If you notice signs of caterpillar damage, such as holes in leaves or cocoons in leaf margins, your “cutworms” are likely representatives of one of the species that I’ve already described in this section.

True cutworms are the larvae of several types of moth, all of which are in the owlet or Noctuidae family, such as the black cutworm (Agrotis ipsilon).

Like armyworms, these are not truly worms at all, but are simply a type of primarily soil-dwelling caterpillar known to target the bases and stems of plants such as cabbage.

The moths lay eggs in early spring. The tiny larvae that emerge can range in color from pink to black, and they begin to feed immediately, especially on tender young seedlings.

Look for them near the base of plants, particularly in the hours after dusk, where they can chew through enough of the stems of plants to sever them entirely.

Between feeding, and when disturbed, cutworms curl into a “c” shape in the soil where they may be confused with various types of grubs.

When they’re ready to pupate, they’ll remain in the soil over the winter, emerging as adults in early spring.

Learn more about how to deal with cutworms in our guide.

Diamondback Moth Caterpillars

The diamondback moth caterpillar is the larva of the diamondback moth, Plutella xylostella. The larvae are yellow-green, bearing a strong resemblance to young cabbage loopers.

They can be differentiated by the presence of a forked “tail” at the end of the body of the diamondback moth caterpillar, and in adult moths, the two species can be easily distinguished.

The diamondback moth is slender, gray, and less than half an inch long, with its wings folded close to the body and a pattern of three diamond shapes on its back.

The adults lay eggs on cabbage and other brassica crops throughout the spring, and the larvae quickly hatch and begin to devour the leaves of the plants.

They particularly relish the tender leaves around buds and blooms that are produced when cabbage bolts, and will gorge until they pupate.

These caterpillars produce white, silk-like threads and can even use the threads to dangle from plant leaves if disturbed.

You’ll notice the silky threads on plant leaves, appearing near “shot holes” or sections where they’ve chewed a lacy pattern into the softer parts of the plant.

In the pupa stage, they wrap themselves in a cocoon of silk threads and attach it to leaves or stems. While they’re fairly small, they can be highly destructive and often blend in easily with plant coloration.

Imported Cabbage Worms

Another green-yellow type of caterpillar to be wary of is the imported cabbage worm. This species is also commonly known as the cabbage white caterpillar, and these are the larvae of the cabbage white butterfly (Pieris rapae).

Butterflies of this species are white, sometimes with a pale green or yellow tinge, and have distinctive dots at the pointed area of their upper wings.

The larvae are velvety, with bodies that taper at the head and the rear, and a clear yellow stripe down the center of the back.

This species is one that many gardeners across most of North America have had to battle for centuries since it was first introduced to the continent from Eurasia.

It’s a pest that practically every experienced gardener has found noshing on our cole crops in spring, summer, and fall, with great disdain.

The adult cabbage white butterfly is capable of laying as many as five clutches of eggs per growing season, which spans from mid-spring to late fall.

The larvae are capable of doing the most damage in early to late fall, when cabbage heads have formed and cooler temperatures are approaching.

Be extra vigilant in the hunt for this species as the larvae have been known to chew plants down to a skeleton, leaving nothing worth saving behind.

Buds, blooms, and young heads are their favorite parts of the plant, but they’ll eat all of it if given the chance.

After they’ve eaten their fill, they’ll suspend themselves from a thread at the underside of a plant leaf, and form a pale green chrysalis, emerging to carry on their life cycle as adults.

Learn more about how to eradicate cabbage worms in our guide.

Flea Beetles

Named after the flea because of its ability to catapult itself a long distance in a single jump, the flea beetle is another pest that will not only damage cabbage crops, but many other leafy garden plants as well.

Two species – the striped flea beetle, Phyllotreta striolata, and the cabbage stem flea beetle, Psylliodes chrysosephala – are known to destroy crops by chewing irregularly sized and shaped “shot holes” in leaves.

A small infestation of these beetles can easily render your entire crop unusable.

The adults are tiny, less than three-eighths of an inch in length. The coloration of adult beetles can range from shiny black to iridescent blue-green, red, or red and black, sometimes with spots or stripes.

They can exhibit quite lovely patterns despite their destructiveness.

Female beetles can dwell in the soil or in garden debris between growing seasons, awaiting temperatures of about 50°F or higher in the spring to begin laying eggs.

Eggs are laid at the base of young plants near the soil, where the maggots that emerge can have easy access to the stems.

They’ll often bore into these and cause breakage and rotting as they gnaw their way through the tender interior. The maggots are yellow-white with darker colored heads.

If they’re not dealt with early on, they will continue to breed, increasing exponentially in number.

Another concern with flea beetle larvae is that, much like with other pests, their habit of chewing on plant parts can lead to the introduction and spread of disease.

Mosaic viruses, blight, and various types of wilt are all commonly spread by these beetles.

Combating flea beetles is a challenge because of their small size and soil-dwelling tendencies.

One of the easiest preventative measures is tilling – turn the soil in the fall, after temperatures have fallen to freezing or below, to expose buried insects. Fall tilling will also make spring planting easier.

You can delay spring planting for a couple of weeks when adults are emerging and looking for places to feed and lay eggs, and immediately use row covers that completely seal young transplants in, barring access that would allow them to take up residence.

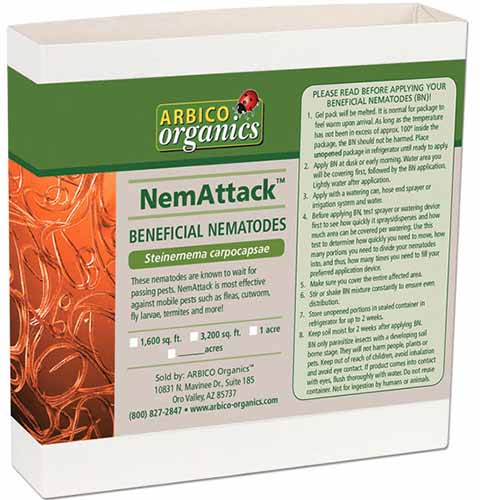

Soil-dwelling beneficial nematodes are a good choice for dealing with flea beetle eggs and larvae as the tiny roundworms will parasitize both and end their life cycle before they emerge as adults.

The nematode species Steinernema carpocapseae is effective against these pests.

NemAttack Sc Beneficial Nematodes

This species of nematode is available from Arbico Organics in quantities ranging from five to 500 million.

Other types of predatory insects are helpful in dealing with the maggots as well.

You can also place sticky traps every few feet between plant rows where jumping beetles may land and be trapped. Catnip and basil can be planted as companions throughout the garden to repel these beetles as well.

Insecticides such as permethrin can be used – but avoid them if possible, and go with the less harmful options except in cases of dire need.

Learn more about flea beetles and how to control them in our guide.

Slugs and Snails

I personally find slugs and snails to be extremely interesting, and enjoy learning about them, but not to the extent that I’m willing to sacrifice my cabbage or other crops to them.

We can be friends as long as they find somewhere else to dine.

These weird, slimy, land-based mollusks can do some serious damage in the garden, particularly on low-lying, soft-leaved plants like cabbage and lettuce. They’ll chew them down to a stubby, wet stump if given the opportunity.

They prefer the cooler temperatures and dewy ground of the evening and night, so you’ll see them at dusk and later, making their way toward the next victim.

A slime trail is typically left in their wake, so if you’re serious about preventing their access to your cabbage, you can bring a flashlight outside and follow those trails to find them and pick them off.

Both snails and slugs lay their eggs in soil, and both are self-fertile, or able to produce viable eggs without mating.

The eggs are typically laid several times per year in numbers close to one hundred at a time, generally in spring and summer.

Avoid leaving debris or yard waste, such as branches and grass clippings, in or near the garden, as both snails and slugs are attracted to the shady, humid environments they create. Cinderblock and wood piles can also harbor them.

There are a number of ways to deal with an infestation, including beer traps, copper flashing and rings, diatomaceous earth, and eggshells.

Read our guide to keeping slugs and snails out of the garden to learn more about the many recommended methods

Spider Mites

Spider mites are about one millimeter in length as adults, making them nearly impossible to see. You’ll note their presence when crops begin to show signs of damage.

When these arachnids are present, plants may show signs of wilt or begin to discolor. You’ll note silvery or white downy webbing, black spots, or sooty mold on the surface of leaves.

Chances are, once you spot these signs of infestation, they’ll already be well-established on your crops.

Just as with aphids, beetles, and other insects that pierce plant parts to feed on sap, mites can also spread disease and kill young plants.

They may infest crops at any time between spring and fall, but will be most active during periods of warm, dry weather.

Avoid planting cabbage near tomatoes, as tomato plants can harbor mites. Weeds should also be removed from your cabbage beds as they can serve as hosts.

Planting marigolds, garlic, or lemongrass near your cabbage patch can help to prevent mites from becoming established.

While providing supplementary irrigation can aid in preventing conditions that are favorable for mites, be aware that wet soil can play host to fungal and bacterial pathogens, or other pests that can easily spread to low-lying cabbage plants.

Neem oil or insecticidal soap can be applied at intervals, according to package instructions, when mites are a concern.

Find Bonide Insecticidal Soap available from Arbico Organics in ready-to-spray bottles.

You can learn more about how to deal with spider mites in our guide.

Stink Bugs

Insects such as the harlequin bug (Murgantia histrionica), a type of stink bug, can be a nuisance despite their interesting patterns.

They may look like the sports cars of the insect kingdom, but they have the same goals as any mundane insect – to eat and to breed.

This type of insect will feast on your cabbage, along with others from the same family, Pentatomidae, that range in color from yellow and black to red and blue.

Other common names for stink bugs include the calico bug, the fire bug, and the harlequin cabbage bug.

Other types of stink bugs that may appear on cabbage crops and other brassicas include the green stink bug (Chinavia hilaris), brown stink bug (Halyomorpha halys), and the southern green stink bug (Nezara viridula).

Much like other pest insects, stink bugs pierce plants with their mouthparts and suck the sap out. This not only potentially leads to the spread of disease, but to wilting, discoloration, and eventual die-off of crops as well.

In the south, eggs can be laid at any time of year, and they’re just as striking as the insects themselves. Their striped or brightly colored, barrel-shaped appearance will stand out against flat surfaces of plants, and you may find them on more than just your cabbage.

The eggs can take a few days to a few weeks to hatch depending on the temperature.

The newly hatched insects are known as nymphs, and they have a simplified pattern and less intense color than the adults. They’re also smaller, but still easy to see against plants in the garden.

The adults are a little over half an inch in length and width, brightly colored and distinctly patterned, and capable of producing strong chemicals with a sulfur-like odor as a defense mechanism against predators, which is derived from their diet of mainly cruciferous vegetables.

These chemicals can cause skin reactions in some people, so it’s important to wear gloves when interacting with them.

Rather than resorting to chemicals and other types of pesticides to deal with these insects, the easiest and least harmful method is to comb over the garden and pull them off the plants when you find them.

You can also shake them off into a bucket of soapy water, if you prefer. Eggs can be dispatched by removing the entire leaf they’re laid on, or scraping them off into a bucket of soapy water.

Other methods of control include regular weeding and removal of garden debris to reduce the number of available hiding places; using row covers to prevent access to plants; and treating plants with neem oil.

Any plants with a large number of insects present may need to be removed, bagged, and thrown away.

Learn more about stink bugs and how to control them in our guide.

Whiteflies

There are many different species of whitefly, but the one most commonly found on cabbage and other brassicas is Aleyrodes proletella.

This species, like many other garden pests, lurks on the underside of leaves, comfortably out of sight.

They’re not able to survive the colder seasonal temperatures in regions north of Zone 7, so you’ll find them mainly in the south, where the warmer climate allows them to remain active in the garden almost year-round.

In cooler climates, you may see them in commercial greenhouses where imported plants have brought annoying guests with them.

You may notice them when you brush against the outer leaves of your cabbage, as they tend to rise in a fluttering white cloud, with a moth-like flight pattern, until they settle back into place.

Whiteflies are – you guessed it – white. They’re also tiny, only about one-twelfth of an inch long.

While they’re definite nuisances because of the piercing mouthparts possessed by both the adults and the nymphs, it takes a major infestation to cause real damage.

Unfortunately, they’ll colonize the external wrapper leaves where they can cause discoloration or moderate leaf die-off, and continue to breed out of control.

The danger with these – just as with other sap-feeding insects – is the chance that they’ll spread disease.

You may notice signs of fungal disease, such as sooty mold on top of leaves where the insects leave behind honeydew, or droppings.

The nymphs are tiny, immobile, waxy little lumps, with an appearance similar to that of scale insects. You’ll find nymphs hatching from eggs in the spring and summer.

One adult female can lay over one hundred eggs, in more than one cycle per season.

The eggs can hatch in about a month, but that period shortens to about two weeks in the hottest part of the summer. They are pale yellow when laid, but change to a brown tone just before they hatch.

If you purchase plants from a nursery or garden center, be sure to check for whiteflies before planting them in your garden, because they’ll easily spread once those plants are installed.

They can also spread to and from indoor plants, so don’t bring any infested material into your home if you’ve got houseplants.

To check for whiteflies, simply brush your hand along the cabbage wrapper leaves and observe whether any adults take flight.

You can also direct a jet from the hose at more mature cabbage heads and disperse some of the flies and eggs with the stream of water.

Whether you see them or not, you can treat your plants with insecticidal soap to prevent infestation, which can be effective against more than just whiteflies.

Apply insecticidal soap according to package instructions in the spring time when insects are beginning to breed in most regions, or throughout the year in regions where winter temperatures are mild.

Be sure to allow garden access to predatory insects and birds, as they can be indispensable assets in combating an infestation.

In addition to ladybugs, praying mantises, and other well-known garden friends, dragonflies also particularly relish whiteflies – and mosquitoes too, so be thankful if you see them hovering around your cabbage patch.

Read more about whiteflies and how to control them in our guide.

Wireworms

The Agriotes genus is comprised of several different species, and the adults are sometimes referred to as “click beetles.”

This name refers to the sound that the insects can make when they’re flipped over and trying to turn back onto their feet.

Different types can be found throughout North America and Europe, and some exist in other parts of the world as well.

As adults, they can be seen crawling rather haphazardly across the soil, and are most often noticed when plant material or soil has been disturbed, as they tend to stay under the soil surface or covered by garden debris most of the time.

When they do appear, it can be startling because they can be quite large – sometimes nearly two inches long.

Adult Agriotes, such as A. obscurus and A. lineatus, have long, sleek bodies.

They can range in color from almost blue-black to dark brown, and some have small, round markings on the back of their heads, or a linear pattern on their bodies.

Their bodies have two segments, with a smaller head and larger thorax.

While adults pose no threat to crops, and they can actually aid in pollination somewhat, discovering them may indicate that larvae are also present.

The larvae are known as “wireworms,” and they are the primary cause of crop damage by these pests.

Wireworms hatch from eggs laid in the spring, and they can live in the soil in larval form for anywhere from two to six years. In that time, they’ll consume organic material, which includes plant roots, and pupate to become adults.

The larvae are light brown to brown, slender, and worm-like, with semi-hard bodies.

They bear a resemblance in body type and coloration to mealworms, and have limited mobility above the soil surface due to the short length of their legs.

They rarely make an appearance at the surface level unless it’s between about 50 and 80°F outside, or if the soil they’re living in has been disturbed.

Typically, when temperatures are higher or lower than this, they’ll bury themselves between six and 24 inches underground.

Some types of wireworms primarily consume only certain crops, such as corn or wheat, while others are less discriminate.

Cabbages, as well as potatoes and other root vegetables, are particularly relished by these larvae, and they can cause quite a bit of damage over more than one garden season.

You’ll notice stunted growth, plant stems that are rotten and weak, and sometimes, tunnel-like holes bored through plants.

Because they can live in the soil for such a long time, and at such significant depths, it can be a challenge to rid the garden of them.

Begin treating for these insects by deeply tilling the soil. Tilling will bring the larvae to the surface where birds and other animals can find them.

You can also introduce predatory nematodes, Steinernema carpocapseae, to the soil that will target immature larvae and eggs, which can lessen the number of larvae that make it to the pupa stage.

Either of these steps can be taken prior to planting or in between planting seasons.

Traps can be helpful in luring wireworms in for removal. You can place a few halved potatoes in holes in the soil dug four to eight inches deep, spread at three- to four-foot intervals around the garden.

Leave them in the holes for three to five days, and then dig them up and check for the worms.

The worms will find the potatoes and bore holes as they voraciously consume them. If they’re present, offer them to the birds, or to chickens or other avian livestock, if you have them.

You can also bag the potatoes up in sealed trash bags and dispose of them. Replace them with fresh potatoes and start again.

A small pile of hay sprayed with diluted molasses can also be an effective trap.

Both larvae and adults will be attracted to it, and they can then be collected along with the hay, and removed from the garden. If you’d rather dispose of the pests, you can simply drop them into a bucket of soapy water.

Unfortunately, there are no effective pesticides available for use on these insects, so they can pose an ongoing battle if the population is allowed to grow beyond your control. It’s best to keep an eye out and catch them early on!

Mammals

Beyond the realm of insects and smaller garden pests, let’s talk briefly about the larger, mammalian species that may join you, uninvited, for dinner.

Deer

Many of us love to see a majestic deer grazing peacefully on our lawns, don’t we? That is, until they find their way into the garden, where a couple of hungry deer can pack away quite a bit of your fruits and vegetables.

Cabbage is, unfortunately, on the list of crops that deer will munch on while foraging, especially in cooler seasons. It can also be very challenging to prevent access to browsing deer without turning the garden into Fort Knox.

A tall fence or sturdy row covers are your best bet to reduce access to your plants. Learn more about preventing crop damage from deer in our guide.

Groundhogs

It’s surprising what – and how much – groundhogs will eat. I’ve lost quite a few crops to them over the years, and many times, I didn’t see it coming.

They particularly love brassicas such as cabbage, as the heads are growing at ground level, allowing for easy access.

These critters are stronger than you might imagine, and they can also chew through many materials or simply burrow beneath fences and barriers.

Groundhogs typically look for grassy areas where hiding is easy, such as roadside ditches or areas around outbuildings, but they often have a separate burrow located in a forested area for their winter slumber.

Filling in the burrow may seem like a viable solution, but those seemingly shallow tunnels can be as much as four to six feet deep. And even if you do fill one in, they will easily dig another.

One pair of groundhogs can produce offspring every year, so you could have multiple generations living in close proximity on your property.

Some gardeners have moderate success with buried wire fencing.

You can dig a trench one foot to eighteen inches deep around the garden and install chicken wire or wire mesh with less than one inch openings to create a barrier that they can’t easily burrow beneath.

Just remember that they have thick teeth and strong jaws – so wire is not always a permanent solution.

Be sure to check for burrows before planting, particularly if your garden is located near fields or grassy spaces.

You can trap them and have them removed if necessary, as it’s difficult to control their access once they’ve decided that your cabbage looks like dinner.

Rabbits

While rabbits can sometimes munch on your cabbage, they are less likely to make a meal of it when other tasty plants are on the menu as it contains sulfurous compounds that can upset their stomachs.

However, in a pinch, if there isn’t much else available, they may decide that it’s worth it.

Much like groundhogs, the easiest way to deal with rabbits browsing the garden is to reduce or remove access. Wire fencing, row covers, and raised beds can help.

Learn more about how to keep rabbits out of the garden in our guide.

Protecting Your Cabbage Crop Can Be Quite the Undertaking

I warned you ahead of time that this was going to be a lengthy list of potential pests, and I wasn’t kidding!

But it’s worth the fight if you enjoy crisp, fresh cabbage for use in those delicious recipes such as coleslaw, cabbage rolls, and a variety of Asian dishes.

Preventive measures are worth every bit of effort they require, and vigilance is key. Nip those potential infestations in the bud and avoid a lot of headaches later on.

Hopefully you’re not discouraged and you feel better prepared – let us know in the comments section below!

And if you found this guide useful, here are some more articles that you might want to peruse on the topic of growing cabbage at home next:

Thank you for this very detailed and comprehensive information. I found the pictures you included very clear and helpful.

You’re welcome, Tracie. Thanks for reading!

Thank you so much!

Thank you so much for this information. As depressing as it is to see all of these pests & know my garden has been attacked by them for years – I do have hope after reading -time to stop reading & get started! THANKS AGAIN!

You’re welcome Sue! Thanks for reading!