Scarabaeidae

A flock of blackbirds were having a lark on my parents’ backyard lawn, scratching, hopping, and gobbling on a patch that had been looking a little sad for a month.

My dad did a little digging of his own and unearthed a few fat, grayish-white grubs.

We never did find out exactly what beetle these larvae were from, but the birds spent a couple days rototilling that spot with their claws. And though it took a few weeks for the grass to recover, they didn’t leave one larva behind.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

Known as the enemy of lawns, white grubs can be hard to notice in time, and difficult to effectively deal with once you do identify them – especially if you don’t want birds ripping up your turf.

Luckily, we’ve got you covered with all the information you’ll need to keep your lawn and garden safe from these root gobblers, including non-avian controls, so read on!

Here’s what we’ll talk about in this guide:

What You’ll Learn

What Are White Grubs?

Sometimes called grub worms, though not technically worms at all, the white grubs you’ll find in your garden and lawn are Scarabaeidae larvae, spanning several genera.

These root-feeding larvae are major pests of lawns and turfgrass, but they will also feed on the roots of edible garden plants such as potatoes and carrots, ornamentals, and weeds.

Their feeding hampers the plant’s ability to draw up nutrients and water, which is why the first noticeable symptoms often resemble drought stress and nutrient deficiencies: wilting, chlorosis (yellowing), and stunted growth.

In lawns, the damage appears as patches of discolored grass that is spongy underfoot.

Though these insects can kill small plants, large plants with strong, well-established root systems often go unscathed.

The adults feed on the foliage, and depending on the species, can cause significant damage to ornamentals and other plants. But that is a topic for another article.

Identification

The common name “white grub” describes the larval stage of several beetle species, and they look very similar. When mature, the larvae measure about an inch long.

Closer inspection with a hand lens can reveal slight differences. The shape of the anal slit, which is the exit for fecal matter, and the raster, which is the hair pattern on the larvae’s last segment, differ between species.

In general, the C-shaped larvae are grayish white with a brownish head capsule, and three pairs of legs, one on each of the first three segments behind the head.

Often, older grubs will have a dark posterior where the contents of the body shine through.

The adults of the common species are a lot easier to tell apart.

European chafers, Amphimallon majale, are oval, half-inch-long golden beetles. Their larvae have Y-shaped anal slits, but the raster spines are arranged in a V or opening zipper shape.

The Japanese beetle, Popillia japonica, is a distinctive insect, about half an inch long with a shiny metallic green head and body, and copper wing covers.

The larvae have crescent-shaped anal slits, and the raster spines are shaped in a short V.

June bugs, also known as May beetles, make up the genus Phyllophaga, which contains over 300 species.

There is some variety in their color, but most are reddish-brown, one-inch-long beetles that are attracted to patio lights at dusk, and will bounce heavily off your door and window screens.

Their larvae have Y-shaped anal slits and parallel rows of spines on the raster.

Biology and Life Cycle

The biology of these pests is similar across the various species, however, the distribution, host preference, life cycle length, and seasonality of these species differ.

There are four distinct stages: egg, larva, pupa, and adult. The larvae go through three instars.

Adult Japanese beetle females tunnel into the soil to lay eggs in July and August, while European chafers do so in late June and July, and June bugs lay in June.

After one to two weeks, the eggs hatch and the grubs begin to feed until the fall. To overwinter, they burrow deeper into the soil.

Once spring returns, the larvae tunnel back up to the roots and continue feeding.

Japanese beetles and European chafers take a total of one year to reach maturity, but June bugs take two to three years, depending on the latitude and species.

The time of year when most of the damage occurs depends on the year of development.

For example, with June bugs, the majority of feeding in their first year occurs in August and September.

In year two, plants will see the most damage from April to September, and if there is a third year, the majority of feeding will occur from April to May.

Once mature, the larvae pupate and emerge as adults. European chafers emerge in mid-June, and Japanese beetles in early July. June bugs emerge from late May to early June in their second or third year.

European chafers cause the majority of their damage in September to November after hatching, and in March to April after overwintering, while Japanese beetles cause damage from September to October after hatching, and April to June the following spring.

In general, the severity of damage increases as the grubs mature and grow larger.

Monitoring

Monitoring is an important part of integrated pest management, as noticing a pest before it causes irreversible damage and before control options become limited is key.

Pay attention to how the soil feels underfoot as you walk across your lawn. If it feels spongy and loose, or if you notice above ground symptoms like wilting, chlorosis, and stunting, do a little digging to see if there are any larvae chewing the roots away.

Use a shovel to remove a patch of turf, and sift through the top three inches of soil and roots to look for the C-shaped larvae.

Keep an eye out for predators too. Mole and skunk damage can indicate a larval pest problem, as well as flocks of starlings or blackbirds that descend on your lawn. All of these animals love to feed on grubs.

When you dig, do a count. Eight to ten larvae per square foot indicates an infestation that can cause significant damage.

Organic Control Methods

There are a variety of methods available to control these lawn enemies, and it is best to approach control with an integrated pest management (IPM) strategy.

Do this by combining available cultural and biological practices, and using chemicals only when absolutely necessary.

Though the adults of some species, especially Japanese beetles, cause damage to foliage, the biggest threat these pests pose is to lawn roots. All of the suggestions below focus on control in grassy spaces.

Cultural and Physical Control

Prevention is key, and the best way to achieve this is to start with plants and lawns that are as healthy as possible. In the summer, don’t mow the grass down lower than two inches, as these beetles prefer to lay their eggs in short lawns.

When preparing to plant a lawn, if possible, thoroughly cultivate the area a year before seeding or laying sod, and remove old plants and weeds.

Care for your lawn by removing excessive thatch, which is the buildup of dead and living plant matter at the base of the plants, aerating, and using fertilizers that are high in potassium, such as Scotts Turf Builder Fall Lawn Food, which has an NPK ratio of 32-0-10.

Scotts Turf Builder Fall Lawn Food

Find this product from Scotts via Amazon.

You can also leave the lawn clippings on after mowing, allowing nitrogen to be released slowly, which benefits the microorganisms in the soil that break down thatch.

Water deeply and infrequently, to encourage deep root development and drought tolerance. The general recommendation is to limit irrigation to once per week, and not to put on more than an inch of water at a time.

Find out how much water your lawn is receiving by setting out a bucket or a rain gauge to collect the irrigation water or precipitation and measure the result.

Moist soil means more pest damage is likely, whereas dry soils can cause the eggs to dry out.

If you notice the adult beetles on your plants, handpick them in the morning when they are still sluggish, and deposit them in a bucket of soapy water.

If possible, plant resistant or tolerant varieties of grass. Fescues and ryegrass naturally contain an endophytic fungus which produces insect-deterrent alkaloids.

This is effective against pests in the foliar feeding adult stage, but unfortunately, the roots don’t produce enough alkaloids to be very effective against the grubs.

Consider planting companion plants such as larkspur and geranium alongside susceptible plants, as they also produce toxic alkaloids which will repel these insects.

Biological Control

Biological control includes the predators and parasites provided by nature, and those purchased and applied by you.

White grubs have several enemies. Ants eat the eggs, birds and certain animals like skunks and moles love the larvae, and there are a few small wasps and flies that parasitize the grubs as well.

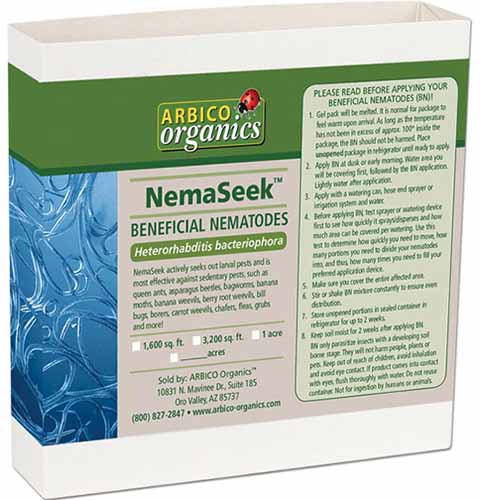

Beneficial nematodes such as Heterorhabditis bacteriophora, available at Arbico Organics under the name NemaSeek-Hb, may be applied either as a preventative treatment, or curatively in mid-August to mid-September.

Nematodes need moisture to do their work, so keep the soil moist but not wet after application.

You can learn more about how to use beneficial nematodes in our guide.

Milky spore, Paenibacillus popilliae, is a good preventative treatment for Japanese beetles, but note that it needs warm soils to be effective.

It is available at Arbico Organics in both granular and powder form. These products can be applied dry and watered in along with nematodes for extra control.

Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. galleriae is a curative product that you can apply in July and September.

It provides good control of all the larval instars. Water in, to a depth of one and a quarter inch.

Organic Pesticides

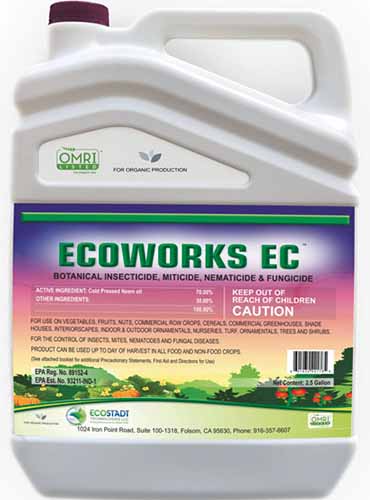

Neem oil products, such as Ecoworks EC, can be useful as a foliar spray as well as a soil drench.

This product is available at Arbico Organics.

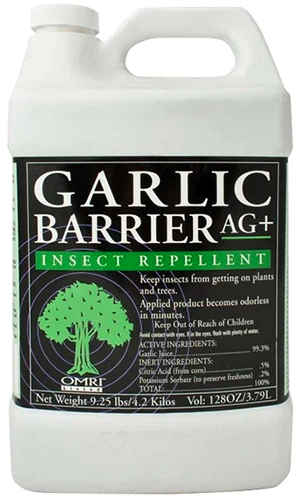

Garlic Barrier, a garlic juice product, can be used as a repellent, discouraging the insects from laying eggs in your lawn and near your plants as well.

This product is also available at Arbico Organics.

Chemical Pesticides

Chemicals can be effective for white grub control when nothing else seems to be working. Depending on the product, they can be applied either as preventive or curative treatments.

Organophosphates such as trichlorfon can be used as a curative, and are most effective if applied from mid-July to mid-October.

Using carbamates such as carbaryl works well as a curative in August.

Neonicotinoids like imidacloprid, clothianidin, and thiamethoxam can be used preventatively or as a curative from April to October.

Cyantraniliprole and chlorantraniliprole are effective as preventative or early curative treatments when applied from April to mid-September.

Keep in mind that many of these chemicals are toxic to beneficial organisms and pollinators. If you decide to apply chemicals, make sure to always follow label instructions carefully!

Underground Troublemakers

Looks aren’t deceiving with these insect larvae. White grubs look nasty pests, and in fact, they are – especially for lawn owners.

There are a variety of methods you can employ to control these root-chewing beetle larvae, including a plethora of cultural and physical methods, a few biological products, and some chemicals to top off your eradication plan if needed.

Have you ever noticed and had to deal with white grubs chewing the roots of your lawn or other garden plants? We’d love to hear how you noticed the problem and dealt with it in the comments below!

And for more information about dealing with pests in the garden, check out these guides next:

Thank you for an excellent report. Did I receive the extract of chili and garlic useful?

Hello Abdelrahman, garlic extract can be useful in repelling the adults from laying eggs wherever you apply it. I am unsure if chili extracts help, as white grubs will attack chili’s as well. Hope this answers your question!

Hops farmer in Central Virginia. Two years ago I noticed some bines not reaching the top wire. Did have a good number of June Beetles, just did not put it all together. Last year no bines made it to top wire and had massive June beetles which I believe is the problem. Treated late summer with grub x, which is not labeled for hops, no I did not sell any last year for that reason. Looking for any suggestions for chemical to treat one last time this spring. Suggestions to me was use pyrethrin granules. Any suggestions would be appreciated.