Otiorhynchus spp.

As I waded through bright-leaved hydrangeas that were taller than I was, I came face to face with a plant covered in leaves notched with half-moon chew marks.

I dove in, inspecting the foliage for clues about who had caused the damage.

Aha! A dead beetle rolled off a leaf as I rustled through, and landed on the ground. I took a photo and moved on, convinced this was a random attack by a now dead beetle, and I didn’t have to worry about a pest outbreak in the hydrangeas.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

Later though, while doing some research, I realized I’d been tricked by that beetle. It was playing dead.

Armed with some knowledge about this strange creature, I removed the pot from the plant and scouted the soil, finding pockets of round white eggs around the roots.

Thanks to that adult beetle’s obvious feeding damage, I’d unearthed an emerging root weevil problem.

Causing both minor cosmetic and more severe damage to a wide range of hosts, root weevils are common – and if you know what you are looking for, they are easy to identify.

So read on to find out how to identify these insects, and discover the control options available to you!

Here’s what we’ll cover in this guide:

What You’ll Learn

What Are Root Weevils?

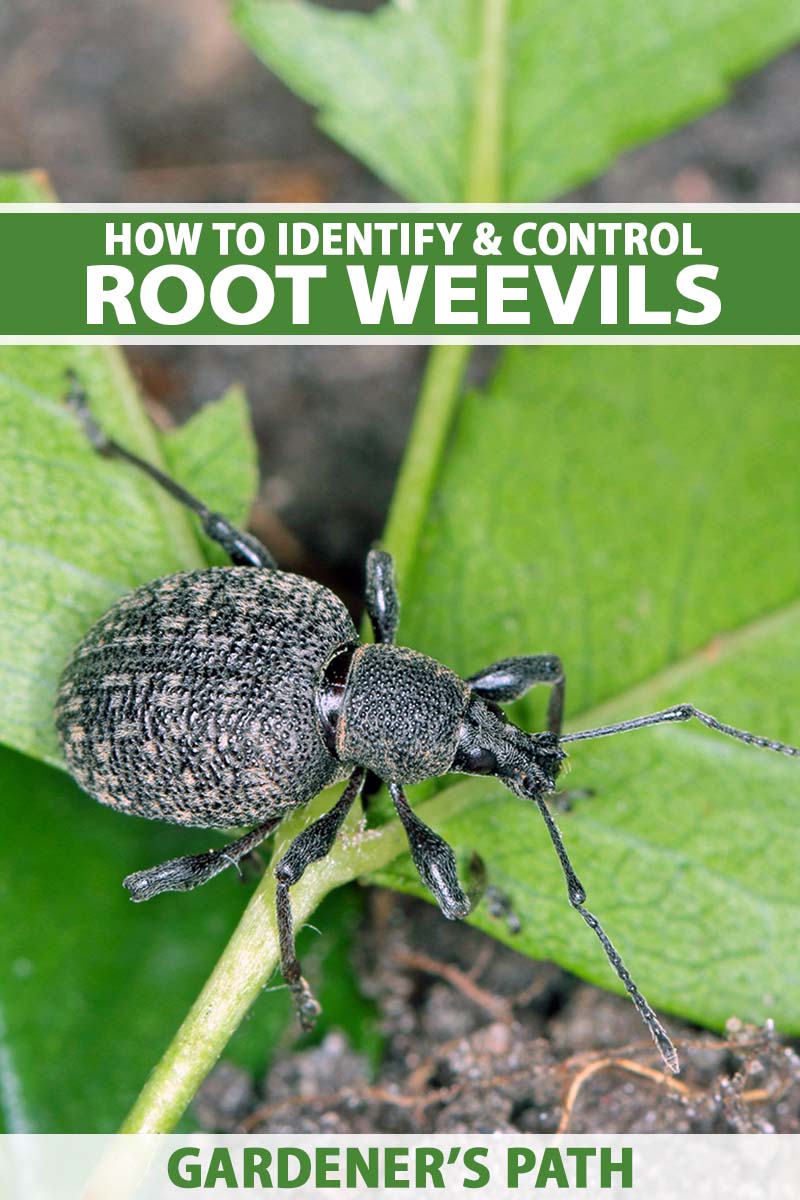

Also known as snout beetles, thanks to their long elephant trunk-like “noses,” root weevils are part of the Curculionidae family in the beetle order Coleoptera.

Both the adults and the larvae may damage a wide variety of hosts, from evergreens to deciduous and herbaceous plants, and food crops as well.

The adults chew ragged D-shaped notches out of the leaf edges, and the larvae feed on the roots. Adult damage is cosmetic, but too many chewing adults can result in sparse new growth.

The real reason we are talking about root weevils here, though, is because of the larvae that like to hide in the soil.

These grubs feed on root hairs, larger roots, and plant crowns, causing reduced vigor, general plant chlorosis (yellowing) that won’t respond to watering or fertilizer, dieback, girdling, and in some cases, death.

Seedlings, new plants, and potted plants are most susceptible.

Identification

Besides some size differences, the different common garden weevil species look quite similar to each other in each of their stages of life.

The adults are brown or black, with hard elytra (wing covers) that are speckled with indentations. The elytra are fused together, so these beetles can’t fly.

Their distinctive snouts and elbowed antennae make them easy to tell apart from other beetles.

The eggs are round, and one millimeter in diameter. They start out white and eventually turn brown.

The larvae are slightly C-shaped, white to cream colored legless grubs with pale orange-brown heads. They range in size from a quarter to a half inch in length.

The pupae are white, and if you find them in the soil, they will have the beginnings of adult features such as legs tucked underneath them.

Many of the common garden species are from the Otiorhynchus genus, including the black vine weevil (BVW), O. sulcatus, which will snack on over 200 species of plants including yews, hemlocks, rhododendrons, euonymus, astilbe, hostas, and peonies.

This species is one of the larger types in the family, with the dark colored adults reaching three quarters of an inch, and larvae up to half an inch in length.

The deep brown strawberry root weevil, O. ovatus, loves strawberries, raspberries, dahlias, and more. The adults are only about a quarter of an inch long, so these are quite a bit smaller than the BVW.

The rough strawberry root weevil, O. rugostriatus, will feed on roses, strawberries, raspberries, gooseberries, and cotoneaster bushes, and lands between the BVW and strawberry root weevil in size, at about four-tenths of an inch long. The adults are clay colored and, as their name suggests, the elytra are deeply indented.

Lilac root weevils, O. meridionalis, are shiny black and about a third of an inch in length. These feed on ornamentals such as lilac, peony, privet, and euonymus.

Biology and Life Cycle

The life cycle is similar across the common species, with some variations depending on the climate.

Most weevils reproduce asexually and never produce males. In fact, BVW males have never been seen.

Females lay upwards of 300 eggs in soil cracks, starting midsummer and through fall. If you have a potted plant that you’ve seen adults on, remove the pot and you may find small groups of eggs laid in pockets on the edge of the root ball against the pot, and throughout the soil.

The eggs hatch about 10 days after being laid, and the larvae move to the roots to feed during what’s known as the first feeding period.

The larvae overwinter in the soil. In the spring, they continue feeding and growing during their second feeding period, which is the most destructive.

After pupating, the adults emerge in mid to late spring, and will feed for two weeks to a month before beginning to lay eggs. This is known as the pre-oviposition stage.

Adults are slow moving, can’t fly, and don’t travel far. They will play dead when disturbed. They are nocturnal, and become more active starting about an hour after sunset.

In mild climates, you can find active weevils or larvae year round, and the life cycle is shifted. The adults emerge in late summer rather than in spring, and they may be active through the winter months and early spring as well.

Root weevils complete one generation per year.

Monitoring

Fortunately, these pests make monitoring easy for us.

The feeding damage done by adults is very noticeable, and since the adults don’t move far or fast, you can assume they have or will soon lay eggs in the soil near the roots of the plants they are feeding on.

Start keeping an eye out for fresh leaf notches in the spring, and monitor your plants throughout the season.

Scout for adults on a cloudy day, or at night when they are active.

Dig up a suspect plant or two to search the roots and surrounding soil for eggs or larvae. The larvae are most easily noticed in the fall or early spring, when they are full grown.

Organic Control Methods

Approach these pests with an integrated pest management (IPM) strategy, combining monitoring with cultural and biological methods for safe, effective control.

When attempting control of these pests, the best option is to focus on the larvae. The adults do not travel far, so killing the larvae will lead to eventual eradication of the population.

Cultural and Physical Control

Established plants with lots of root biomass are much more tolerant of root weevil feeding than fresh new seedlings and young plants.

Start with healthy plants, and choose resistant cultivars if they are available.

Since these insects can’t fly, they are spread via infested plants, soil, and debris. Inspect all incoming plants. Remove and dispose of crop debris.

Go through your plants at night, handpicking or dislodging the beetles into a pail.

Set up pitfall traps by sinking cups into the soil, so the cup lip is even with the soil surface. Partially fill them with a mixture of water and soap.

You can choose to cover the traps with a curved tile, or construct a little roof of some kind to keep rain and irrigation water out.

Keep in mind these traps are not selective for beetles!

On trees and shrubs, use masking tape slathered in a sticky material on the lower trunks and stems, to catch the adults as they crawl up to feed in the evening.

Stiky Stuff is a recommended product that’s available from Arbico Organics.

Cultivate the soil in April to expose the grubs to the sun and hungry birds.

Use small grain or cereal plants as cover crops or rotate with these, as they don’t serve as hosts for root weevils.

Biological Control

Encourage ground foraging birds to visit the soil around your plants, and hopefully root up some grubs, by adding a layer of shredded oak leaves underneath your plants.

One of the most effective treatments for root weevils is drenching nematodes into the soil to target the larvae and pupae. Make sure to note the soil temperature at the time when you want to treat, to choose the best option.

Use Heterohabditis bacteriophora when soil temperatures are above 42°F.

These nematodes target stationary pests including pupae, and are available at Arbico Organics in varying amounts as NemaSeek Hb.

NemAttack and NemaSeek Combo Pack

Or purchase NemAttack and NemaSeek Combo Pack Sc/Hb, also from Arbico Organics, which combines Steinernema carpocapsae, a nematode which attacks active pests like the larvae, and H. bacteriophora.

Apply nematodes in mid-July to mid-September, and maintain soil moisture to keep the nematodes alive.

Organic Pesticides

Several organic pesticide options are available to home gardeners to deal with these pests.

Beauveria bassiana is available in certain formulations as a biopesticide, such as BioCeres WP, which is available at Arbico Organics.

These products may be applied to foliage as a contact insecticide, and may provide some control of the feeding adults.

AzaGuard Insect Growth Regulator

Azadirachtin acts not only as a repellent, but also works as an insect growth regulator. AzaGuard is available at Arbico Organics.

Chemical Pesticides

Pyrethroids such as esfenvalerate and fluvalinate; neonicotinoids such as imidacloprid, clothianidin, and acetamiprid; carbamates such as carbaryl; and organophosphates such as malathion will kill root weevils, especially adults.

However, it is difficult to effectively control them in the most destructive stage, which is when they are underground, with pesticides. The best option for that is a nematode drench as described above.

Apply chemical pesticides targeting adults during the pre-oviposition stage, after hatching and before egg laying. This is a period of about two weeks after the first sign of leaf notching. Apply late in the day, when the adults become active.

Young larvae are more susceptible to pesticides as well, so you should time pesticide applications for grubs when they are newly hatched and feeding on the roots.

Most of these pesticides are not selective for pest insects, and they will have negative effects on beneficial insects and pollinators. Use them only as a last resort, and follow package instructions carefully.

Nosey Beetles

Since both adults and root weevils in the immature stages feed on plants, these insects are not a welcome find.

They can affect a wide variety of hosts, meaning you are almost certain to have something growing in your garden that these grubs will love to snack on at some point.

Nematodes are one of the best options for controlling the larvae, and not only are they safe for beneficial insects, they will attack a variety of other pests as well!

Plus, there is an assortment of cultural and physical control options available for you to try.

Have you ever noticed D-shaped notches munched out of your plants’ leaf margins? Do you think one of these long-nosed beetles may have tricked you by playing dead? Tell us about it in the comments below!

And for more information about other pests in the garden, check out these guides next:

I applied hb to my peonies and rhodies last spring, with little effect. I now see that my lilac thicket in a different part of the yard also is affected. Should I apply more, or at a different season?

Sorry to hear it, Donna. Yes, I would give treatment another shot. As described above, temperature is important when applying beneficial nematodes and you’ll need to follow the package instructions closely. Summer is usually the best time for application.