Delia radicum

Cabbage maggots are small insects that can have a huge impact on cole crops, such as cabbage, broccoli, turnips, rutabaga, radishes, cauliflower, and brussels sprouts.

The larvae live in the soil, feed on the fibrous roots, and then tunnel into the roots and stems.

These insects can totally destroy a crop.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

Read on to learn how to monitor and control this garden menace.

What You’ll Learn

Identification, Biology, and Distribution

Cabbage maggots are usually found in the northern zones of the US, since cole crops are cool-season vegetables. However, they can also be found in warmer climates, such as the coastal regions of California.

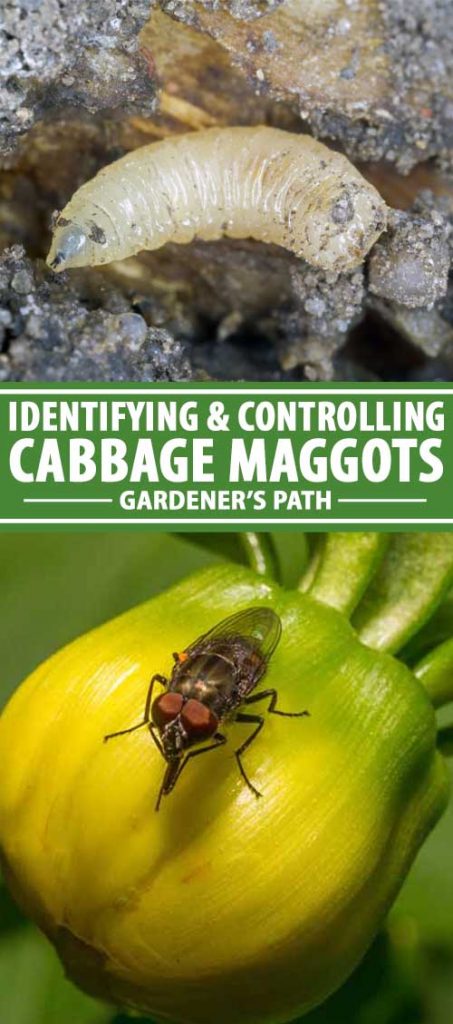

Cabbage maggots are the larvae of Delia radicum, or the cabbage fly, which is also known as the cabbage root fly, root fly, or turnip fly. These are often mistaken for houseflies, although they are about half the size.

The white eggs are about 1/8 inch long and shaped like torpedoes. They are often laid in rows near the main stem of cruciferous vegetables.

The eggs are most likely to survive in cool, moist soil. If temperatures exceed 95°F in the top 2-3 inches of the soil, this will kill the eggs.

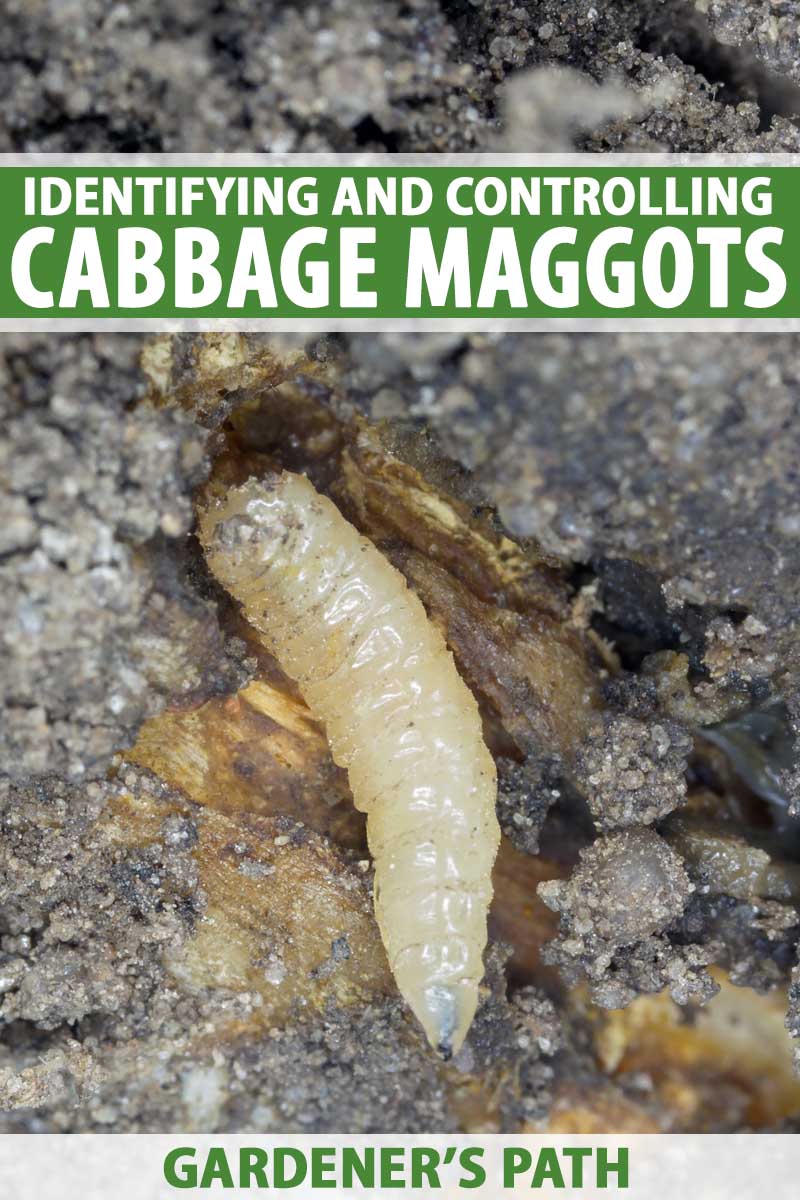

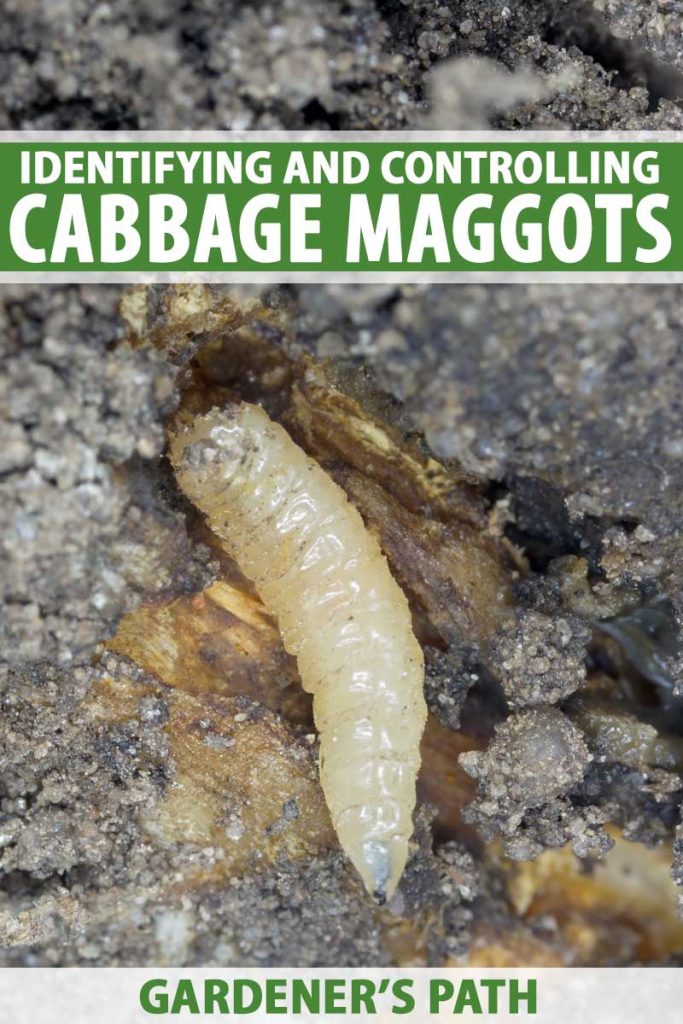

The maggots are about 1/3 inch long, white with no legs. They are pointed at one end.

Life Cycle

These pests overwinter as brown pupae in the soil near the roots of fall crops.

The flies emerge from the soil in early spring in the north, and in the fall and spring in areas with warmer climates, such as California. They can travel as far as a mile to find host plants!

The adults will feed on pollen and nectar for 10 days or so, and then they lay their eggs at the base of the plants. The larvae will hatch in about a week.

After hatching, the larvae tunnel through the soil to the root system, starting with the fibrous roots. They can completely destroy root systems.

Older larvae may tunnel into the stems of plants as well.

The larvae pupate in the burrows they leave while digesting the the root material, and then emerge in 2-3 weeks to start the cycle over again.

Damage

Unfortunately, since cabbages and other cole crops are cool-weather vegetables that need to be grown early in the season to avoid the heat of the summer, this leaves them vulnerable to springtime visits from these pests.

Cole crops that are planted in the winter or spring typically suffer more damage than those planted in the summer or fall.

Since cabbage maggots are so small and live in the soil, you may not even realize you have them until your plants start wilting. Infested plants are particularly likely to wilt on sunny days.

Turnips and radishes are exceptions, and these do not wilt. This makes it more difficult to identify infestations in these crops.

Slightly blue or yellow foliage is another sign of infestation.

The larvae will be visible on the roots when you pull up the plants, although by that time, it is usually too late to save them. The infested plants will wilt, collapse, and die.

Even if radish, turnip, and rutabaga plants survive, extensive damage from the feeding tunnels will render these crops inedible or unmarketable. And root damage leaves stressed plants more susceptible to fungal disease, and other problems.

Monitoring

It is important to be aware of when the spring flight occurs to have a chance of saving your plants. This is the period when females fly close to the ground, depositing their eggs.

Surprisingly, a weed can help you pinpoint this occurrence. Monitor when wintercress (aka yellow rocket, Barbarea vulgaris) is blooming, if it grows in your area. This is often an indication that the flies are on the march. Er, fly.

Stiky Strips® Yellow Sticky Traps via Arbico Organics

You can use yellow sticky card traps to attract the files. Hang them slightly above the tops of your plants.

Look for the eggs along the stems, or in and on the soil near the stems of young plants. If you are growing in a wide area, check groups of 2-5 plants in different areas of your garden for signs of these insects.

If you find even one egg per stem that you check, the numbers in their total local population can explode exponentially from that point, and it is likely that your plants will suffer significant damage.

You may find more eggs in wetter parts of your garden, so keep an eye out.

Cultural Controls

You can use cultural methods to minimize the chances of infestation.

Be Careful Where You Plant

Planting your cabbages in areas that were not planted with fall cole crops previously will help to reduce populations of these maggots. The greater the distance from previous cole crop planting sites, the better.

Also avoid planting in areas that recently held decaying organic matter. Examples of this include areas in which a cover crop or animal matter was plowed under.

Use Floating Row Covers

Floating row covers can help protect against these insects. As soon as you plant your seeds or transplants, install a row cover, and cover the edges with soil.

Do not use row covers in areas where cole crops were grown the previous year, or you could end up with an infestation under the row cover!

You can remove the cover once the soil warms up, and the plants have become large.

Pile Soil Around Stems

Another thing you can do to help your plants resist succumbing to an infestation is to bring soil up around the stems.

This will encourage the plants to grow adventitious roots, which can help cabbage and other crops compensate for any root loss.

Till Crop Residue Under

These insects can survive for quite a while in crop residue.

After you have harvested your fall crop, till the residue under. This will bring the pupae to the surface, where they will die.

Organic Chemical Treatment

An organic plant-based treatment known as Ecotrol G is an option for organic chemical treatment.

According to R. Hazzard of the UMass Amherst Center for Agriculture, Food, and the Environment, this granular product is composed of plant oils that may repel these insects.

Ecotrol G is certified for organic production by the USDA.

Biological Controls

There are several options for the biological control of these pests:

Beneficial Nematodes

Applications of the beneficial soil nematode Steinernema feltiae have been shown to work against this pest in trials.

You should apply the infective juvenile nematodes to the transplants in water. You can spray it on, or apply it as a drench before or after transplantation.

NemAttack™ – Sf Beneficial Nematodes via Arbico Organics

If the adults begin flying less than a week after transplanting, you will need to treat the plants after transplanting them. Use a concentration of 100,000 to 125,000 of the juveniles per transplant.

And make sure to keep the soil moist, so the nematodes will survive.

Read more about using beneficial nematodes here.

Natural Enemies

Beetles that live in the soil can kill large numbers of the eggs, larvae, and pupae. The beetle species Aleochara bilineata parasitizes the larvae by laying its eggs on the surface of worms.

If you rely on these beetles, you should not treat the soil with insecticides.

Predatory mites and parasitic wasps are additional enemies that will feast on the maggots.

If you are lucky, the maggots may be attacked by a fungus that occurs naturally. This is more likely to happen when the flies are abundant, and in high relative humidity. Of course, then you will have to deal with fungal disease on your plants.

Chemical Pesticide Controls

Insecticides can be used to control these maggots under some circumstances, but they will not always be effective.

Also, keep in mind that you will not need to use them if surface soil temperatures are above 95°F for several days in a row, since such temperatures will kill these insects.

Options for chemical control include diazinon and cyantranilprole.

Focus on the seed furrows, or the base of plants if you are treating transplants. Be sure to follow package instructions, and follow the application with a lot of water, to help the insecticide penetrate into the soil.

If the insects are well established, insecticide sprays will not control them effectively.

There is no point in applying insecticides if there are tunnels in the roots, but no maggots. This indicates that the maggots have moved on to pupate, and this type of insecticide application will be ineffective.

Monitor and Take Action!

Cabbage maggots can have devastating effects on cole crops.

These insects are so tiny that they are easy to miss – until it is too late for your crop.

Monitoring your plants carefully can alert you to their presence when populations are still low enough to give you a chance of controlling them.

Control options range from beneficial nematodes to insecticides.

Have you had a cabbage maggot infestation in your crop? Let us know how you fared in the comments.

And read on for more information on cabbage pests, such as:

© Ask the Experts, LLC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. See our TOS for more details. Product photo via Arbico Organics. Uncredited photos: Shutterstock.

So, I am super disappointed that today I found two of my hardy cabbage plants wilting in beautiful warm sunshine after a couple days of gentle rain. I poked around and saw swarms of maggots on the roots. I was distressed, because I just put in a huge garden and I don’t want to lose all my plants after a month of hard work. I remembered reading that you can kill fungus or root rot with hydrogen peroxide mixed with water. I thought, “What do I have to lose? These are going to die anyway.” So, I pulled back the… Read more »

Hi Brianna, That sounds heartbreaking to have your plants so heavily infested with cabbage maggots! I was unfamiliar with the use of hydrogen peroxide to kill them, but it is even registered by the EPA to treat agricultural crops. I’m not sure about your strategy of treating the roots of your so far untouched plants. Hydrogen peroxide breaks down pretty quickly, so I’m not sure if it would stay around long enough to kill new invading insects. Please keep us posted on how your strategy works. That would be wonderful if it works for you, and I think a lot… Read more »

How did you make out with your procedure. I am so interested in knowing

It was a couple years ago, but it didn’t go well. ????

I put a mesh net over my crop of Brussel sprouts yesterday and today there were lots of cabbage flies under the net. The cover was loosely on with obvious gaps as I hadn’t finished it. It almost seemed like a plague. Could the soil have been full of pupae or is it likely they have found a way in and not been able to get out? Is it an active time of year – seemed like a lot of flies. How many flies would visit one brassica on average a day?

Hi Annabelle, That sounds dreadful! Yes, it is a common problem to put on a net while there are pupae in the soil and then end up with a massive infestation. I would suggest checking around the roots to see if there are signs of the maggots. If not, that would suggest that the flies did indeed fly in through the gaps in the mesh. Also, are your plants wilting? If so, that would suggest that they have an infestation of cabbage maggots at their roots. In addition to traditional insecticides, there is a product called Ecotrol G that is… Read more »

What happens if you accidentally eat one of them?

Eating one of these pests accidentally isn’t commonly a cause for concern. Some bacterial food poisoning issues have been reported after accidental ingestion of housefly maggots, but this was caused by harmful bacteria carried by the flies that contaminated the food the larvae (and later humans) ate. You should be OK! Always remember to rinse homegrown produce well before cooking or eating, to remove pests, dirt, and debris.