Anthomyiidae

The sun is blazing down on your vegetable patch, and as the day heats up, you notice your cabbage is looking a little wilted.

That’s weird, the soil seemed moist enough when you checked early this morning…

Turning into a sleuth, you inspect the leaves. They’re free of pests, but you notice they’ve got a yellow tinge.

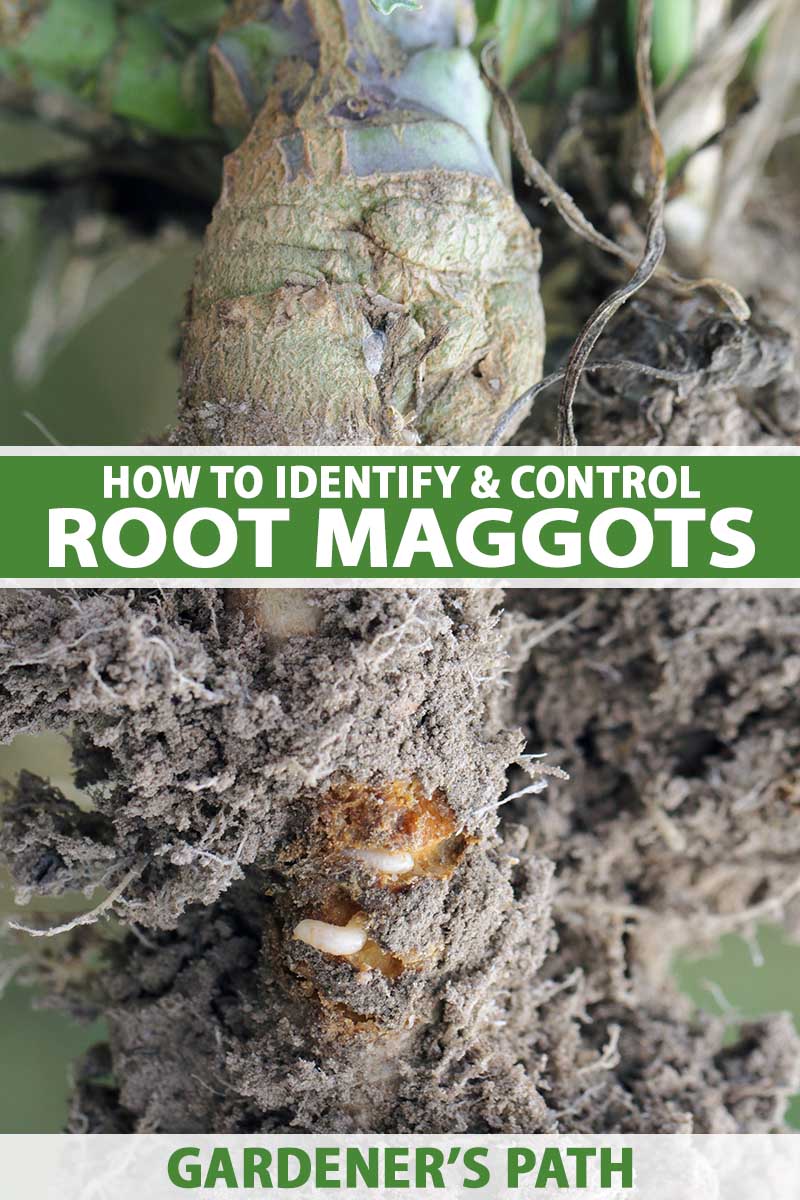

You pull a plant out of the ground and – aha! There are small holes tunneling into the roots.

As you hold the root up to get a closer look, a tiny white larva pops out, wondering who turned on the light.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

Root maggots aren’t a fun find, but we’ve got everything you need to know about these insects covered in this guide, including control options!

Here’s what we’ll talk about:

What You’ll Learn

What Are Root Maggots?

Root maggots are part of the Anthomyiidae family in the Diptera order. There are about 39 genera and 640 North American species.

Some are harmless or even beneficial, feeding on decaying matter and feces, or preying on other insects. And the adults of some species are important pollinators, such as those in the Crinurina and Fucellia genera.

The ones we as gardeners need to be worried about are those in the immature stages that like to feed on the stems and roots of our crops. Many of the most common pest maggot species are in the Delia genus.

The larvae burrow into the fleshy roots and bulbs of a wide variety of crops, including onions, carrots, and cabbages, causing the plants’ growth to be stunted and leaves to turn yellow.

The primary symptom though, is wilting, especially during periods of hot and dry weather.

To add insult to injury, the holes in the roots serve as a perfect entry point for fungi and bacteria, leading to potential secondary issues with rot and decay.

Crops which are grown for their edible underground parts can be rendered completely inedible by the damage, and early spring plantings can be killed.

Identification

The adults and larvae of most pest species look almost identical, but they’ll be found on their specific hosts.

The cabbage root maggot, Delia radicum, is a very common garden type, infesting cabbages, cauliflower, turnips, radishes, and other crucifers. The adults have two dark bands on the upper thorax.

The onion root maggot, D. antiqua, another garden regular, loves onions, shallots, leeks, and chives. The adults are slightly larger than D. radicum flies.

While not necessarily a root-targeting species, the seedcorn maggot or bean fly, D. platura, loves to snack on the endosperm of crops with large seeds, such as corn, beans, peas, and melons.

Plus, it will attack the hypocotyl (germinating seedling stem) and cotyledons (seed leaves) as the seed germinates and grows underground. D. platura larvae are about half the size of those of D. antiqua.

The turnip root maggot, D. floralis, is almost an exact replica of D. platura in terms of appearance. It will attack the same crops as D. radicum, but prefers turnips if they are available.

In general, the adults look like half-sized houseflies. They are gray-toned and bristly.

The eggs are small, white, and oval with tapered ends.

Fly larvae are often called maggots. Root fly maggots are white or have a yellow tinge, with a blunt tail end. They can be six to 10 millimeters long.

The pupae are brown, oval, and about a quarter of an inch long.

Biology and Life Cycle

Each species’ peak period of adult activity happens after a certain number of growing degree days (GDD).

What does this mean?

Growing degree days are days when the temperature exceeds a certain minimum for a specific crop or insect to develop. For root maggots, the minimum temperature for development is 40°F.

For Delia radicum, first-generation peak activity occurs at 452 GDD, while the peak occurs a little later for D. antiqua, at 735 GDD.

Knowing this number can be useful to predict when the adults will be mating and laying eggs, so you can plan treatments accordingly, or delay planting until the period of peak activity is over.

Root maggots overwinter as pupae. The adults emerge from the soil and begin flying. Adults mate when they are six days old, and begin laying eggs three to four days later.

Over their approximately 30-day lifespan, females lay 50 to 200 small eggs divided into three batches, taking a break of a few days in between batches.

The eggs are laid in cracks in the soil or on plant stems at the soil level, and these take four to 10 days to hatch.

After hatching, the larvae burrow into the ground, and feed for three to four weeks before pupating near the surface of the soil. It takes them two weeks to emerge as adults.

The number of generations per year depends on the region and the species, with most typically completing between one and four generations.

Monitoring

Your crops are most susceptible to damage as seedlings and during cool, wet springs. As soon as the plants emerge, watch for wilting – especially on hot days – and chlorosis.

If you suspect root maggots are present, pull a few plants up and inspect the roots or bulbs for burrowing larvae.

If you find tunnels but no larvae, they’ve already pupated, and it is too late to apply insecticides.

Some growers set up yellow sticky cards to trap and monitor for adult activity.

Keep an eye on indicator plants such as Barbarea vulgaris for an idea of when these pests are active.

Better known as yellow rocket or wintercress, the bloom period for this yellow flower coincides with the beginning of the cabbage maggot’s spring flight.

Organic Control Methods

Approach these pests with an integrated pest management (IPM) strategy, combining monitoring and methods such as good sanitation, exclusion, and crop rotation for safe, effective control. Learn more about how to use IPM in your garden in our guide.

Cultural and Physical Control

Prevention and sanitation are key.

Your aim should be to get your plants through the most susceptible periods, such as during and immediately after germination, and during periods of cool, wet weather. Moist, cool soils favor egg laying and survival.

Plant susceptible crops in raised beds so the soil can dry out and warm up, discouraging egg laying. Temperatures higher than 95°F in the top two to three inches of soil are lethal for eggs.

If possible, delay planting until the first flight and period of peak activity is over, and the soil temperature is high enough to kill the eggs.

Determining this is based on reaching GDD thresholds and will vary by region. But in general, late May or early June is a safer time to plant or sow seed than earlier in the spring.

Consider using floating row covers to protect your plants as they emerge and strengthen.

Physical barriers to prevent the flies from laying their eggs in or near your plants are very effective, provided the spot hasn’t had root maggot issues before, since the pupae could hatch under the row covers if they are already in the soil.

Remove any dead or dying plants, and leftovers after harvest. Rototill crop residues into the soil immediately after harvest to remove overwintering sites.

Grow resistant crops or varieties if possible. For example, red cabbage varieties are resistant to D. radicum.

Biological Control

Birds, ants, spiders, rove (staphylinid) and ground (carabid) beetles, tiny wasps such as Tribliographa rapae, and nematodes will all attack these insects.

Several types are available for purchase, so you can intentionally apply them to your garden.

Staphylinid beetles, such as Aleochara bilineata, are probably the most important natural enemy of root maggots, with both adults and pests in the immature stages attacking larvae as well as adult flies.

NemAttack Beneficial Nematodes

Apply a mix of the beneficial nematodes Steinernema feltiae and S. carpocapsae, which is available at Arbico Organics to control larvae and pupae.

Dalotia coriaria, a species of rove beetles, are also available at Arbico Organics, and these feed on the larvae in the soil as well.

Organic Pesticides

As these are underground pests that like to hide inside the roots of plants, there are not many effective pesticides available, neither organic nor chemical.

A lime drench made by adding one quart of water to a cup of agricultural or garden lime can be effective. Let the mixture sit overnight and use the clear liquid to soak the soil around the plant.

Diatomaceous earth, rock phosphate, or wood ashes sprinkled around the plant can also have a limited effect.

Perma-Guard Diatomaceous Earth

Perma-Guard Crawling Insect Control, a diatomaceous earth product, is available for purchase at Arbico Organics.

As for the adults, Ecotrol Plus, which contains a variety of aromatic oils, can repel the flies.

Chemical Pesticide Control

There are no chemical pesticides currently available to treat the soil for cabbage or onion maggots prior to planting. And you can’t rescue existing plants from seedcorn maggot damage with chemicals either.

The chemicals available for root maggot control include the organophosphate diazinon, and cyantraniliprole.

While products containing these chemicals can be applied during an infestation, they are not selective and will affect beneficial insects as well.

Since natural enemies contribute to control in a huge way, consider all the cultural and physical control options first to avoid killing the good insects in your garden!

Channelling and Chewing

Infested onions and wilted cabbages can ruin what should otherwise be a joyful harvest.

Besides tunneling directly into underground plant parts that we want to eat, these hungry larvae can cause yellowing and wilting of above ground parts that we grow for food as well.

Plus, their tunnels provide entry points for disease.

Luckily, now you know there are beneficial insects on your side, plus there are a variety of cultural and physical control options to try to combat these excavating insects.

Have your crucifers ever wilted without explanation? Or have you noticed tunnels in your shallots? Tell us about your experiences with root maggots in the comments below!

Plus, read more about fly pests and how to control them in the garden here:

Fantastic….

Very much useful. Thank You