Beets often top lists of “perfect plants for beginners” because they aren’t too much of a challenge to grow.

So it’s extra devastating when you step into your garden to discover that those plants you were counting on have been struck by some mysterious ailment.

Don’t lose heart. Every plant is prone to disease now and then.

Fortunately, you’ve come to the right place to figure out what’s going on, and what you can do to fix it and prevent the same problems from recurring next year.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

Once you know what challenges your beet plants face, you can take steps to head many of them off before they get a toehold.

Here are some of the most common beet diseases you might encounter:

15 Common Beet Diseases

Some of these diseases can be avoided altogether if you keep pests away, so be sure to check out our guide to dealing with beet pests.

Ready to get started?

1. Alternaria Leaf Spot

Alternaria leaf spot is caused by various species of fungi in the Alternaria genus.

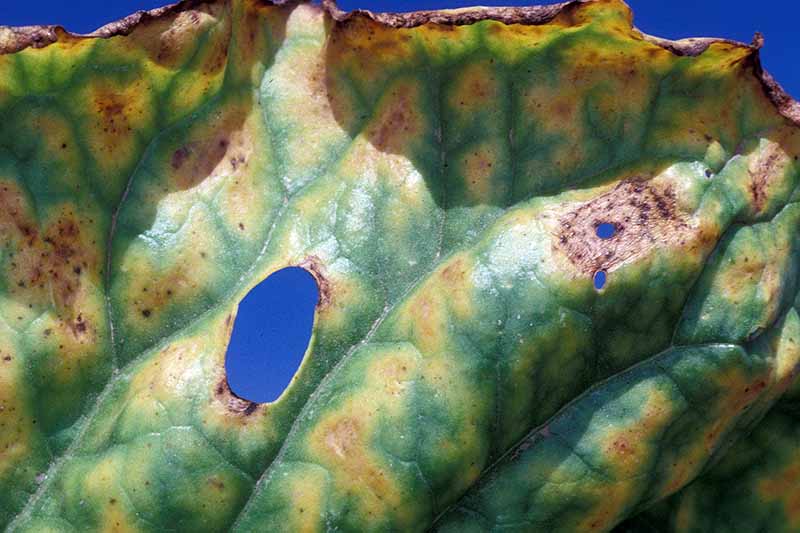

Small, round lesions will appear on the leaves. The lesions may fall out, leaving holes, or they can merge and cause parts of the leaf to turn brown and necrotic.

This disease thrives in humid and hot conditions.

While the damage is mostly cosmetic, it can reduce your leaf harvest.

The best way to avoid this disease in the first place is to rotate your crops, and wait three years before you plant anything in the goosefoot family in the same location again.

You should also be sure to water at the base of the plant and not on the leaves themselves. Keep weeds out of your garden beds as well.

If you are determined to get rid of this garden foe, you can use a product that contains hay bacillus, also known as Bacillus subtilis.

CEASE biological fungicide, which contains this beneficial bacteria, is available at Arbico Organics.

You can apply it as a foliar spray several times a week, if the infection is so bad that it is causing a majority of the leaves on your plant to die back.

Learn more about how to use Bacillus subtilis in your garden here.

2. Bacterial Leaf Spot

Bacterial leaf spot (aka bacterial blight) in beets is a disease caused by the bacteria Pseudomonas syringae pv. aptata.

You’ll know if your plants are infected if the leaves exhibit circular spots with irregular edges. The spots will look dry, with a brown or tan color on the interior and dark borders.

These spots can turn yellow and appear water-soaked before they turn necrotic and rot. They may also run together, making leaves look ragged – or the leaves may drop off entirely.

This disease is spread by water, and via rain or irrigation, as well as by aphids. The bacteria thrives in moist, warm conditions.

It may also be spread by wind and garden tools, so it can be hard to avoid.

The first step for preventing this disease is to use mulch around your plants to prevent splashing water from landing on the leaves.

Then, be sure to sterilize your gloves, spade, and other garden tools each time you use them. I use a mix of 10 percent bleach and 90 percent water.

As a preventative measure, you can spray plants once a week with neem oil or Bonide Revitalize, a biofungicide containing Bacillus amyloliquefaciens, which you can find at Arbico Organics.

Revitalize is simple to use. Mix it with water according to package directions, and spray it on the foliage of your plants once or twice a week.

You can learn more about how to use Bacillus amyloliquefaciens in this guide.

If you notice mild symptoms of an infection, trim off the affected leaves. Then, sit back and let your crop grow, continuing to monitor for signs of disease. With any luck, your beet roots will grow large enough that you can still eat them.

If you find that the disease has returned, continue to trim off the affected leaves if you can. Otherwise, you will need to pull and dispose of the plants.

Once your plants have a serious case of this disease, there is no way to get rid of it. Pull your plants and destroy them, or put them in the trash.

This is a particularly good idea if you have other beet, chard, melon, or squash plants in the garden that aren’t already infected.

Don’t put infected plant parts in your compost, or you risk spreading this disease all over your garden.

3. Beet Curly Top

This disease is caused by a variety of different viruses in the Geminiviridae family.

If your plant has it, you’ll notice the leaves crinkling and curling inward. They may also be stunted, small, and discolored, with purple margins.

The signature telltale sign of infection is swollen veins on the bottom half of leaves. The stems become stiff.

Underground, the roots become twisted and stunted, and start losing their ability to take in nutrients. Th is causes the foliage to turn yellow and stop growing. As a result of this chlorosis, they’re unable to photosynthesize or absorb sunlight and will eventually wilt and die.

The infectious viral pathogens are primarily spread by the beet leafhopper, Circulifer tenellus.

This little insect is about 1/8 of an inch long, and pale green or yellow in color. Leafhoppers will jump or fly from plant to plant, and they eat tomato and potato foliage as well as that of beets.

If you live in the eastern half of the US or in Canada, you don’t have to worry. This pest is only a major problem in the West, throughout the western US and Canada, and all of Mexico.

It’s also a problem in southern Europe, and northern and southern parts of the African continent.

If this disease is a problem in your area, planting resistant cultivars is recommended. You can contact your local agricultural extension office to see if there are any locally-adapted cultivars that are resistant to the virus.

To prevent the bugs from landing on your plants, use floating row covers to protect them. You should also keep weeds out of your garden to deny them a place to hide.

4. Beet Mosaic Virus

Beet mosaic virus is caused by viruses in the Potyvirus genus. If your plant gets infected with this disease, you’ll start to see small, light colored flecks on the youngest leaves.

Later, the green of the leaves in between the veins turns pale and yellow.

Next, the older leaves start to show the same symptoms before all the leaves eventually progress to turning necrotic. Below ground, the root can become stunted.

Ready for some good news and bad news?

Bad news first: once this disease shows up, there isn’t anything you can do to stop it. Your best bet is to pull the plants and put them in the trash, not your compost, to prevent it from spreading further.

The good news is that it’s entirely spread by aphids. Why is that good news? It means if you keep your garden free from those tiny pests, you’re home free.

Keep in mind that you need to keep aphids away. Some places will tell you that once your plants have the disease, you need to check and get rid of any aphids. That won’t help. When they land on your plant and dig in, they’ve already spread the infection.

First, you can plant trap crops, like nasturtiums, nettles, and asters to attract aphids. In between your trap plant and your beets, grow repellent plants like marigolds, dill, and catnip.

Finally, intersperse plants like cilantro, common geraniums, and cosmos to attract beneficial ladybugs, which love to devour aphids.

On top of that, you might want to add a reflective mulch to the ground all around your plants, but keep in mind that it increases the heat, so you don’t want to use it when the weather starts to warm up.

Finally, you can spray plants with a mixture of four parts mineral oil to one part dish soap. This smothers the bugs if they do happen to make it onto your plant leaves.

5. Beet Rust

Beet rust is caused by the fungus Uromyces betae. Like other rusts, it appears as small reddish-orange spots on leaves.

It also weakens foliage, which makes it so that when you go to tug your beets out of the ground, the leaves give way. This makes harvesting a real challenge.

While the roots will still be edible, you’ll need to dig around them and hoist them out of the ground, rather than having the leaves to assist you in pulling them up.

The fungus thrives in cool, wet weather and can overwinter on plant debris or in seeds. Look for certified disease-free seeds as a first line of prevention.

Beyond watering at the base of plants rather than sprinkling the foliage, and giving plants the right amount of space when planting, your best line of attack is to use a foliar fungicide.

CEASE is a reliable option, as described above. You can apply it as a foliar spray once a week as a preventative, or twice a week to treat a rust infection.

6. Beet Western Yellows

Beet Western yellows is caused by a virus (BWYV) that makes leaves turn yellow in between the veins. It usually starts with the older or outside leaves.

Later, red spots will form and the leaves will become thick and brittle. They may even turn white.

Despite the name, it doesn’t just impact beets. It can also destroy lettuce, peppers, and radish plants.

Keep aphids under control, since they spread the virus. You should also keep weeds away from your garden, many types of weeds can serve as a host for the virus.

If your plants become infected, there’s nothing you can do. Pull your beets and destroy all the plant material. Don’t place it on your compost pile.

7. Cercospora Leaf Spot

The fungus Cercospora beticola causes cercospora leaf spot in beets. Look for brown or gray spots with reddish halos on the leaves of plants.

These can eventually merge and cause the foliage to turn necrotic.

It’s spread by wind and rain, and it favors high temperatures and high humidity.

It’s always a good idea to rotate your crops, especially if you’ve come across this disease in your garden. Don’t grow plants in the Beta genus in the same place more often than once every three years.

Be sure to water at the base of plants to prevent moisture from landing on the foliage. You should also apply mulch around the base of plants to prevent water splashing up from the soil.

As described above, CEASE can help you tackle this problem.

Read more about identifying and treating cercospora leaf spot on beet plants.

8. Damping Off

Damping off is caused by several different species of fungi, including Aphanomyces cochlioides, Rhizoctonia solani, Phoma betae, and Pythium ultimum.

Seedlings may fail to emerge, or they might collapse when they’re young.

You’ll often see a water-soaked stem at the base, which will look thin and brown. You may also see black roots if you pull up the seedling.

It’s often identifiable by a fuzzy white mold on the surface of the soil as well.

While lots of plants may be affected by damping off, beets are extremely susceptible. The good news is, if you’re planting directly in the garden rather than transplanting your root crops, it’s less common.

Make sure plants have adequate airflow by planting them four inches apart in rows 18 inches apart, and avoid overwatering. Clean your tools with a 10 percent bleach solution before working in the garden.

You should also use fresh potting soil, and sanitized or new containers if you are starting seeds indoors or growing your crop in a container.

Outdoors, dig down one inch and spread a thin layer of a phosphate fertilizer like DTE Rock Phosphate, available at Arbico Organics, at planting time.

Cover this with an inch of soil and place your beet seeds in the top soil layer to prevent damping off.

Learn more about how to prevent damping off here.

9. Downy Mildew

Downy mildew is a disease caused by the water mold (oomycete) Peronospora farinosa. It favors cool temperatures and high humidity.

As the name suggests, it can cause a downy brown, tan, or gray growth on leaves. Foliage can also become puckered or thick.

Managing water on plant foliage is absolutely essential to preventing this disease. Whatever you can do to keep moisture off the leaves in the morning will go a long way toward keeping this pathogen at bay.

That means watering at the base of plants, applying mulch around them to prevent splashback, and watering in the late morning instead of at night.

You should also prune out a fifth of your beet leaves at the first sign of disease, to increase air circulation and allow any water or dew that’s present to dry more rapidly.

Because beets grow in cool temps, this often coincides with the time of year when many regions are getting a lot of rain.

That means you might not be able to control the amount of water that lands on the leaves.If this is the case for you, use a preventative fungicide like ZeroTol, which is available from Arbico Organics.

Spray plant foliage once a day using a diluted mixture, according to package instructions. Be aware that it can cause leaf damage, but it won’t harm the roots growing underground.

10. Fusarium Root Rot

The fungus Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. spinaciae causes root rot in beets.

Early on, the plants may look wilted during the day but they won’t perk up when you add water. At night, the plants appear to recover.

As the disease progresses, leaves become dry and brittle, and you may see yellowing in between the veins.

You can tell that the problem is fusarium rather than sun scorching because it typically only impacts half of a given leaf. One side will often look completely normal while the other is practically dead.

Underground, the beetroot rots away.

Keep weeds out of your garden, since these types of fungi also live on pigweed and lamb’s-quarter. It can also live in the soil for up to seven years.

Fungi thrive in moist conditions, so be careful not to overwater. You should also rotate your crops. Don’t plant beets in the same place more than once every three to five years to prevent recurrence of this disease.

Once you detect fusarium root rot or yellows, it’s too late to stop it. Pull your plants and dispose of them.

11. Fusarium Yellows

Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. betae causes yellows. The symptoms are identical to those of fusarium root rot, but instead of causing the roots to rot away, they develop a grayish-brown interior.

As with root rot, there is no cure. If you spot signs of this disease, pull your plants and throw them in the trash.

To prevent the problem from recurring next year, follow the same steps laid out for above fusarium root rot – rotate your crops, weed your garden beds well, and be careful not to overwater.

12. Powdery Mildew

Powdery mildew is a common problem that attacks all kinds of plants. If you garden long enough, it’s almost certain you’ll encounter it.

There are many types of fungi that cause this disease, but beet plants are impacted by Erysiphe betae in particular.

Watch for white circular patches of a fuzzy growth on plant leaves.

Later, the leaves will look like they’ve been covered in a dusting of flour. Eventually, they can turn yellow and this can reduce your root and leaf yields.

This disease is most common in warm, humid weather conditions with temperatures between 60-80°F.

If you have dealt with this issue in the past, make a 50-50 mix of milk and water and spray leaves every few days as a preventative measure.

You should also water first thing in the morning, so the foliage has time to dry out in the sunlight – and be sure to water at the base of plants.

While the disease isn’t spread by water, it favors areas with poor air circulation and damp, humid conditions in the soil and on plants. Planting in well-draining soil with the appropriate spacing is key.

Check for the recommended spacing on your seed packets.

As the plant grows, consider snipping off a few leaves from each plant to improve air circulation.

If only a few leaves are impacted, cut them off with a pair of clean shears.

If that fails and your entire plant is covered in mildew, use neem oil or a product containing potassium bicarbonate, like MilStop, which you can find at Arbico Organics.

Mix MilStop with water according to package directions, and apply it to the base of plants.

13. Scab

Scab is a disease caused by the bacteria Streptomyces scabies.

In addition to beets, it infects other root crops like potatoes, turnips, and carrots.

If your plants have it, you likely won’t know until you dig up your roots, at which point you’ll see large, round spots that can either be ruptured, or tan and woody.

The good news is that you can usually still eat the roots, you just need to peel the skin and scabby damage off.

If you have struggled with scab in your vegetable garden in the past, try to maintain your soil at a pH below 5.5. This will go a long way toward keeping scab away. You should also keep the soil watered well.

Though it’s true that a pH level of 5.5 is more acidic than what’s ideal for growing this root crop, in this case, it’s a matter of risk versus reward. The beets might not be quite as robust, since acidic soil can inhibit nutrient uptake – but you won’t have to worry about scab.

Regular crop rotation is also important. Don’t plant root vegetables in the same spot in the garden more than once every three years.

14. Southern Blight

Southern blight sounds positively Biblical to me, and like some sort of plague, it can destroy your crop.

You might be breathing easy because you’d assume with a name like “Southern,” it would only attack plants in the southern reaches of the US. Not so.

It has been found in crops as far north as Wisconsin when the weather conditions are right (or wrong, as the case may be). That means temperatures anywhere between 80 and 95°F when the humidity is high.

If you’re growing your plants during the cooler parts of the year, you should be home free. But there’s no guarantee that you won’t have a warm spell, or that this disease won’t sneak in even when temps are cooler.

It’s caused by the fungus Sclerotium rolfsii, and when it hits, you’ll see what look like water-soaked spots on the stems and leaves of your beets. It tends to appear on the parts of the plant near the soil.

You’ll also see white threads that form on the plant and along the soil surface. Underground, roots may start to rot.

It spreads in a number of ways, including on contaminated tools and in contaminated soil. It also hangs out on weeds, mulch, and on plant debris. On top of that, it spreads through water as well.

Because the fungus favors moist, humid conditions, make sure you’re planting your beets with the appropriate spacing. Trim away a few leaves if the temps start to climb, to promote good airflow.

You should also put a layer of mulch on the ground, to prevent water from the soil splashing up onto the leaves. Plastic mulch can be used preventatively to create a barrier between uncontaminated soil and the pathogen.

You can also use a preventative fungicide to stop this disease. Terraclor is considered one of the best options. It should be used as a soil drench, following the manufacturer’s directions carefully.

You shouldn’t handle the plants or area where you used the fungicide for at least 12 hours, and wear protection while applying it.

If you want to skip the chemicals, your best bet is to pull the plants and destroy them if they contract Southern blight. Then, turn the soil at least four inches deep to expose the fungus to sunlight.

Rotate your crops, making sure not to put plants in the beet family in the same area for at least three years.

15. Verticillium Wilt

This disease, usually caused by the fungi Verticillium dahliae and V. albo-atrum, attacks a wide range of plants, including beets.

It gets into plants through the roots and causes older leaves to start yellowing, progressing to newer leaves.

It may impact just one side of the plant, or the whole thing. Eventually, the leaves can die back, killing the plant.

The bad news is that there’s no effective treatment available for verticillium wilt. You should pull your plants and dispose of them. Don’t put them in the compost or you risk spreading the disease throughout your garden.

After disposing of infected plants, you should till up your soil and cover it with clear plastic for up to a month, in order to solarize the soil and kill the fungus. This works best in the summer, when the weather is hot.

After solarizing, don’t plant in that location again for at least four years to be on the safe side.

Don’t Let Diseases Get You Down

Dealing with diseases, even in easy-to-grow plants like beets, is all part of the process of gardening. Don’t let it discourage you.

I like to look at it as a learning experience. Once you’ve dealt with something like powdery mildew enough times, you’ll know better how to deal with it in the future.

You can refer to our complete guide to growing beets if you need a refresher on good gardening practices.

If you do end up finding a disease in your crop, let us know what you’re facing and what worked best for you in the comments below.

And for more information about growing beets in your garden, why not check out these guides next:

Is there any danger to humans if a beet has any of these diseases and the root is eaten?

Hi there, the answer is: it depends. Most plant diseases are specific to plants. But they leave the plant exposed to pathogens that can actually harm humans. Leaf diseases like Cercospora or mosaic virus are safe if you are eating the root. Conditions cause rot or fungal infection are generally safe, but you should cut away any of the diseased material. Don’t dry or can any diseased veggies. Eat them right away.

My red beet plants were beautiful, then all of a sudden they look like they are dining. And it looks like it is spreading to rest of the plants. What can I do?

Hi Wendy, could you tell me a bit about what your weather has been like? Is the soil soggy, moist, or dry? Do all of the symptomatic leaves look like the one in the picture? Do you see any different symptoms on other plants? I have a few guesses as to what is going on, but some additional information would help me narrow things down with more certainty.