The beet, Beta vulgaris, is a biennial root vegetable that is commonly cultivated as an annual in temperate zones.

Plants are grown primarily for their reddish purple, red and white striped, yellow, or white edible roots, but the leafy tops, or beet greens, are equally delicious.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

In our series of articles about beets, we discuss topics ranging from garden cultivation and health benefits to container gardening and pest control.

In this article, we zero in on a fungal beet disease, Cercospora leaf spot.

Here’s the lineup:

What You’ll Learn

What Is Cercospora?

Cercospora leaf spot is a disease caused by the Cercospora beticola fungus. It preys upon the oldest, outermost leaves of a plant, killing them and feeding upon the dead plant tissue.

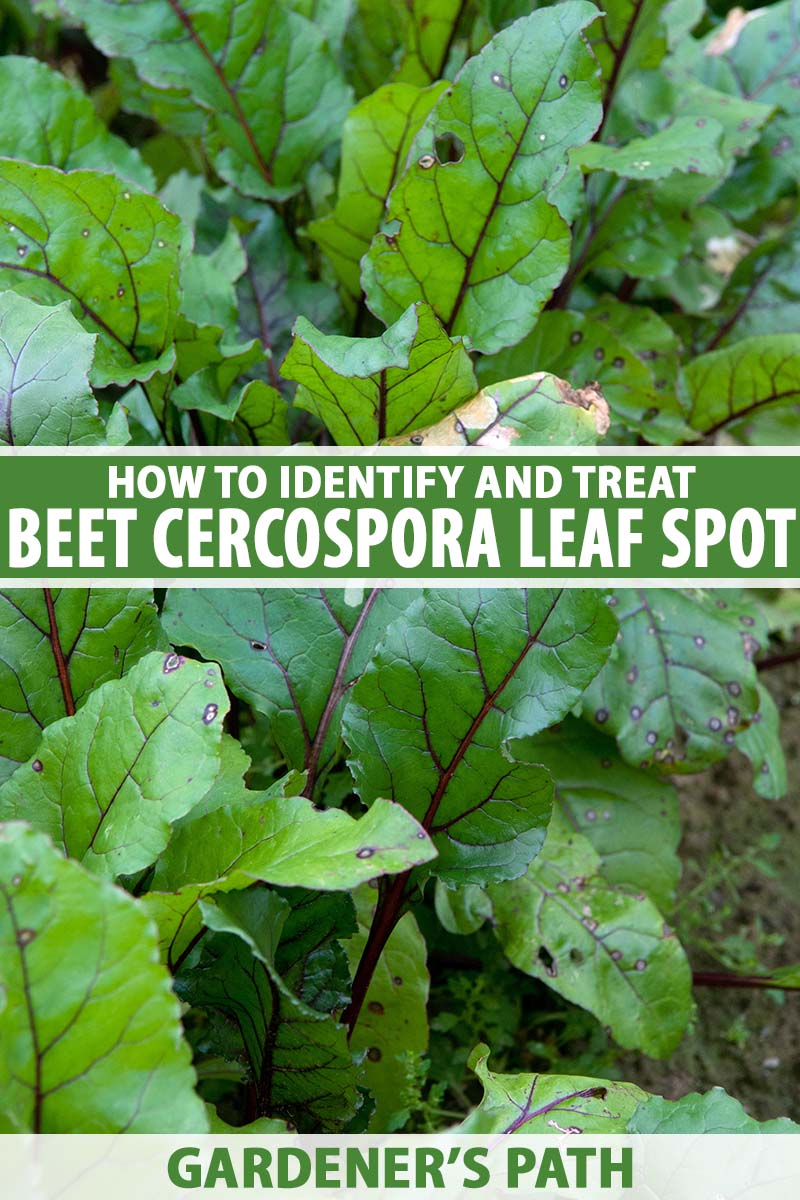

Tell-tale signs are “necrotic lesions,” or dead patches, that look like tan circles with a reddish outer band. As the disease progresses, a glimpse through a microscope would reveal a minute “fruiting body,” or spore-releasing structure, in the center of each.

Unchecked, the tan circles merge together, forming large dead areas that turn gray as spores envelop them.

This fungus plagues late-summer crops cultivated in hot weather with high humidity, especially when the foliage is wet during nighttime hours.

And as the first photo shows, it may appear in tandem with pest damage, such as the trails made by leaf miner larvae.

In cases of extensive infection, beet roots may fail to mature.

C. beticola spreads readily with a simple splash of the garden hose, or on the back of an insect or bottom of a garden shoe, especially when plants are crowded.

One of the greatest challenges with managing this fungus is its ability to winter over in garden debris, such as weeds and infected plant material that is discarded during harvesting.

Proactive Avoidance Measures

To minimize the risk of crop failure due to disease, take action of a preventative nature.

Start with disease-resistant seeds purchased from a reputable purveyor. Poor quality seeds may contain fungus, and be doomed from the start.

Meet your plants’ needs for full sun and organically-rich, well-draining loam.

Avoid overcrowding, which can increase ambient humidity and leaf wetness, by spacing plants three to six inches apart, depending upon mature beet size.

Plant in early spring to avoid maturation during the hottest, most humid parts of the growing season.

Because C. beticola favors wet conditions, it’s important to avoid overwatering. Beets don’t need to be oversaturated. An inch of supplemental water in the absence of rain is adequate.

Also, when you water, take care to aim the hose at the roots in the soil, not over the foliage. Wet foliage is a prime target for fungal development.

Opt for drip irrigation instead of spraying, to keep the leaves dry.

Keep the garden free of weeds and debris, to prevent the wintering over of fungal spores that may ruin next year’s crop.

The beet is in the Chenopodium, aka goosefoot, family of plants that includes quinoa and Swiss chard. Be sure to rotate crops in this family to new sites every few years to reduce vulnerability to C. beticola.

Note that it can also adversely affect spinach, which is in the Amaranthaceae family, as well.

And most importantly, consider a pre-treatment with a foliar fungicide to inhibit disease from the start.

Here’s a product to try – MilStop® SP Foliar Fungicide is a powder that’s available from Arbico Organics. It contains potassium bicarbonate, and comes in five- and 25-pound packages.

Follow the package instructions and note that while this product is labeled nontoxic, it should not be inhaled during application.

Damage Control

Unfortunately, if your beets succumb to C. beticola, there’s little you can do to halt its progress. Fungicides applied to leaf spot kill spores on contact, but don’t prevent more from being released, nor do they protect healthy foliage.

However, at the first sign of trouble, you can remove the affected outer leaves. Discard them in a sealed bag in the trash and sanitize your pruners afterward.

If the damage is extensive, you may have to forgo the beet greens, but you can harvest roots as small as one inch in diameter, for the sweetest, most tender beets you’ve likely ever had.

Cercospora Is Unwelcome Here

It’s very upsetting when a lovingly tended crop succumbs to a disease that threatens to ruin it.

The weather is certainly beyond our control, but with an understanding of C. beticola and the proactive measures you can take against it, you may never have to deal with an outbreak.

Add the following to your garden planner today:

- Purchase disease-resistant seeds

- Provide ideal growing conditions

- Space plants appropriately

- Plant early to avoid peak heat and humidity

- Avoid overwatering

- Keep the leaves dry

- Weed and clear debris

- Apply fungicide preventatively

- Rotate crops

Fostering an environment that is less conducive to fungal development greatly reduces the threat of C. beticola, and is the best way to address this plant pathogen.

If you found this guide useful, and are interested in reading about more common vegetable diseases, we suggest the following: