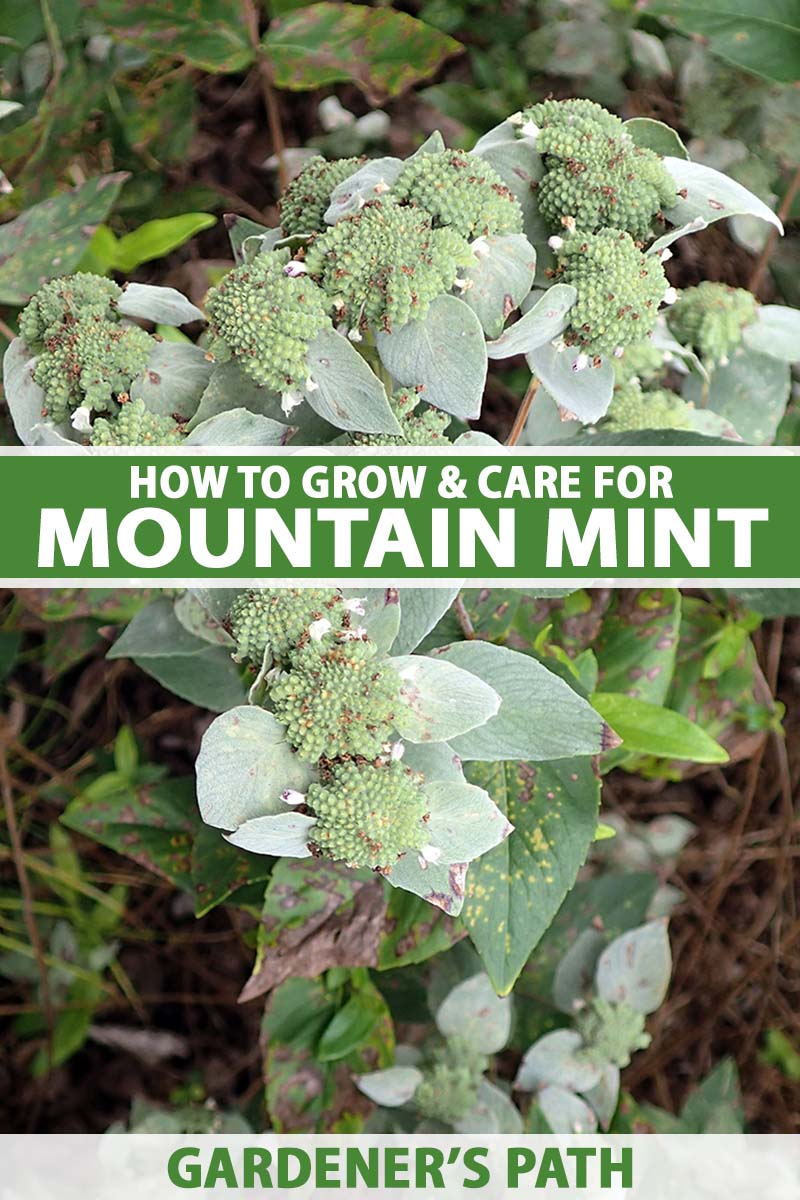

Pycnanthemum spp.

Mountain mint is a beautiful, fragrant herb that attracts bees and butterflies like a magnet.

If you’re interested in providing pollinators with food and habitat, add one or more of these plants to your yard or garden!

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

This perennial herb holds a special place in my heart, and I hope that when you grow your own, it will have one in yours as well.

In this article you’ll learn how to propagate silvery-hued mountain mint, what type of light, water, and soil conditions it needs, as well as ideas about how to use it in the landscape.

Here’s a sneak peek at what we’ll cover:

What You’ll Learn

Before we get started, let me tell you – mountain mint is the plant that turned me into a native plant convert.

Many years ago, I bought a small pot of clustered mountain mint (Pycnanthemum muticum) from a local native plant sale in North Carolina, expecting fun opportunities to witness bumblebees or maybe some honey bees visiting my garden.

I did not anticipate what actually happened.

When my clump of P. muticum bloomed, there was an all out pollinator party in my backyard. It was as if a message went out calling all beneficial insects far and wide to attend. I couldn’t even count the number of different species I was seeing!

I witnessed this spectacle with awe and experienced first hand the power of growing native plants.

You may be thinking that my pollinator parade was simply anecdotal, but actually, my experience was not unique.

Researchers such as Kaitlin Swiantek at the University of Florida have conducted studies on the Pycnanthemum genus, and found that these plants attract a huge diversity of beneficial insects.

In one of the studies, it was determined that mountain mints are even more popular than milkweeds and goldenrods, which are known to be wildly attractive to pollinators.

Sure, non-US native plants like zinnias and cosmos will attract bees and even hummingbirds. But natives like Pycnanthemum species take wildlife care to another level.

We’ll be focusing primarily on P. muticum in this article, but we will cover a few other species from this genus as well, so keep reading to learn more!

What Is Mountain Mint?

P. muticum, also known as clustered mountain mint, is an evergreen perennial that has a clump forming growth habit, with plants reaching one to three feet tall and wide.

Oval- or spear-shaped leaves are dark green, have toothed margins, and grow opposite on branching, square stems. This foliage has a delightful, minty fragrance.

Inflorescences appear at the ends of stems in summer, and the flower heads have large, grayish white bracts that give the whole plant a silvery appearance.

The actual flowers are small, have two lips, and are white, pink, lavender, or blue in color.

Cultivation and History

Native to the US and Canada, the Pycnanthemum genus contains 19 species, 13 of which are found in mountain mint hot spot North Carolina.

Habitats for these species are diverse, including moist and dry woodlands, sandy soils, rocky slopes, streambanks, meadows and clearings, prairies, thickets, and moist bluffs.

The Pycnanthemum genus is categorized taxonomically in the mint family, Lamiaceae.

Members of this genus are related to a diverse array of garden staples including peppermint, basil, coleus, as well as houseplant favorites such as Swedish ivy.

Within the true mint subtribe, Pycnanthemum is closely related to bee balm, another pollinator favorite.

One of the most widespread members of this genus, P. muticum is native to the eastern central and eastern US.

In its native range, mountain mint is found in fields, meadows, and open woodlands, and can be grown in USDA Hardiness Zones 4 to 8.

As already noted, this genus is an excellent choice for wildlife care. In fact the University of Georgia State Botanical Garden named mountain mint one of the Pollinator Plants of the Year for 2022.

And of course, as you might expect from an aromatic plant, you can use the leaves of this perennial as a refreshing herbal tea!

Mountain Mint Propagation

Ready to start growing this fragrant perennial? Mountain mint can be propagated via seeds, cuttings, division, or transplanting.

From Seed

You can grow mountain mint from seed, but for improved germination rates, seeds need a cold, damp stratification period.

To achieve this, sprinkle the seeds on a damp paper towel. Fold the paper towel in half, then half again, and place it in a plastic bag. Store the plastic bag in the fridge for one to two months.

After the stratification period, gather your supplies: you’ll need four-inch nursery pots, growing medium, and a spray bottle for watering.

Glass Spray Bottle With Adjustable Nozzle

Do you need a spray bottle for projects like these? You can find a glass spray bottle with an adjustable nozzle available via Amazon.

Fill the nursery pots with moist growing medium, such as Rosy Soil’s Seedling seed starting soil mix, available for purchase via Amazon.

Rosy Soil Seedling Seed Starting Soil Mix

When filling the nursery pots, leave a gap of about an inch between the surface of the soil and the rim of the pot.

Take several seeds and press them onto the surface of the soil, but don’t cover them – they need light for germination.

Moisten the growing medium with a spray bottle, and place the pots in a location with bright indirect light, and keep them in a temperature range of 65 to 75˚F, using bottom heat if needed.

You can keep seedlings warm by placing them on a heat mat, such as the Jump Start Heat Mat from the Hydrofarm Store, available for purchase in an assortment of sizes via Amazon.

Keep the soil moist but not soggy as seeds germinate and seedlings become established.

If started indoors, harden seedlings off when they have several true leaves before planting out.

To do this, move them outdoors to a protected, shady location for an hour or so, gradually increasing the amount of time and direct exposure to sun and wind over the course of about a week.

Once these young mountain mint plants are hardened off, they will be ready for transplanting.

While seeds can also be sown directly outdoors in fall, your chances of success will be much higher when starting them in pots, since the seeds are so tiny.

Save yourself some disappointment and use pots instead of direct seeding.

From Cuttings

The best time to propagate mountain mint from cuttings is in early summer. For this project, you’ll need growing medium, rooting hormone, and four-inch nursery pots.

It’s ok to reuse old nursery pots but be sure to clean and sterilize them first.

Prepare the pots first by filling them with moist growing medium, leaving a gap of about an inch between the surface of the soil and the rim of the pot.

Using sterilized garden pruners, take four inch cuttings, making your cut just below a set of leaves. Snip off the bottom set of leaves from each cutting.

Dip the end of the cutting in rooting hormone such as Olivia’s Cloning Gel, available for purchase in an array of jar sizes from Arbico Organics.

Poke a hole in the center of the growing medium, then insert the cutting, firming the potting medium around the base. Place these in dappled shade and keep the growing medium moist.

The cutting should form roots in a few weeks – you can check by pulling on the stem to see if it resists pulling out of the growing medium.

Once the mountain mint cutting is rooted, gradually acclimate it to direct sunlight by increasing sun exposure over a period of about a week.

After this acclimatization period, your cutting will be ready to transplant.

By Division

Mountain mint grows from rhizomes, which can be divided when plants are dormant, either in late fall or early spring.

Before you start dividing this herb, a day or two ahead of time, water both the mountain mint patch and the transplant location.

The day you’re ready to divide, first dig a hole that is about twice as deep and wide as the root ball of the division you’re planning to separate off from the main clump.

Take a shovel full of the soil you just dug out and mix it with an equal part of compost, then put this mixture back into the hole.

Now it’s time to divide the existing clump of mountain mint. Take a shovel and slice through the plant’s roots – you can take half of it or less for the new clump.

Work the shovel under the plant’s rhizomes and lift the clump out of the ground.

Carry the lifted clump to the new location, or if needed, place it into an empty pot to transport it.

Place the clump into the hole on top of the mix of soil and compost – adjust the amount of soil underneath the clump so that the top of the plant’s root ball is level with the ground.

Water in and cover the soil around the mountain mint plant with an inch or two of mulch.

Want more details? Find step by step instructions for dividing perennials in our guide!

Transplanting

Once you have an established mountain mint seedling or have purchased a plant in a nursery pot you’ll need to transplant it either to a larger container or into the ground.

If you’d like to try the container method, be sure to read our article about growing herbs in containers.

To transplant a specimen into the ground, first choose a day with mellow weather, if possible, or wait until the late afternoon when the day has cooled off. Cloudy days are ideal for transplanting.

Dig a hole twice as deep and wide as the specimen’s nursery pot – plan to allow one to three feet of space for each plant.

Put a shovel full of the soil you removed from the hole back into the hole and mix it with an equal amount of compost.

Remove the specimen from the nursery pot, loosen its roots, and mix any growing medium that comes off the roots into the hole with the soil and compost.

Place the root ball into the hole, adjusting the amount of loose soil mixture beneath it to keep the top of the root ball level with the ground.

When it’s level, backfill with soil, then water in. If the soil level sinks in after watering, add more soil, then pat the soil gently to level it out.

Water in again, and cover the area around the plant with an inch or so of mulch.

If the weather is hot or dry, be sure to water every couple of days or more frequently to keep the soil moist as the plant gets established.

How to Grow Mountain Mint

Mountain mint thrives in full sun or part shade, but flowering will be best in full sun.

This silvery herb requires well-draining soil that is rich in organic matter, with a pH between 6.1 and 7.3.

Although it has some drought tolerance, P. muticum grows best in moderate to moist conditions, so water plants during hot weather and drought as they get established.

Growing Tips

- Situate in full sun to part shade.

- Provide moderate to moist conditions.

- Grow in soil rich in organic matter.

Maintenance

Mountain mint is a low maintenance plant. Maintenance tasks include pruning, as well as dividing when desired or when a plant is growing beyond its allotted space in your landscape.

Pruning this perennial is easy. Since this is a stellar plant for pollinators, ideally you’ll prune to create bee nesting spots.

To do this, leave all the dried stalks in place over the winter. In spring, cut just a few of these back half way and prune the rest of the stalks down to the soil.

The stalks left standing will provide nesting spots for bees in spring.

Learn more about creating habitat for bees, as well as other actions you can take to help them in our article!

As for dividing, this task is only required if you want to prevent the plant from spreading, which it does slowly, and not like it’s bent on taking over the world like its relatives in the Mentha genus!

When mountain mint is dormant, you can divide mature plants to keep them at the desired size, as described in the propagation section above.

Mountain Mint Species to Select

The main subject of our article is P. muticum, also known as clustered, blunt, or short toothed mountain mint.

Reaching one to three feet tall and wide, this one is known for its silvery bracts and shallow teeth on the margins of the leaves.

Choose this species if you are in the eastern or eastern central US, Zones 4 to 8, and can provide moist growing conditions in full sun to part shade.

Purchase P. muticum as a live starter plant in a three-inch pot from Sacred Roots Nursery via Walmart.

In addition to P. muticum, there are 18 other species of Pycnanthemum.

Here are a few of interest:

Hairy Mountain Mint

P. verticillatum var. pilosum, also known as P. pilosum, hairy, American, or whorled mountain mint, is native to the eastern and central regions of the US.

Reaching one to three feet tall, this species has narrow green leaves and clusters of small flowers at stem ends and at leaf axils.

It grows in full sun or part shade in dry to medium soils that have good drainage, in Zones 4 to 8.

You can find P. verticillatum var. pilosum seeds in a selection of packet sizes from Everwilde via Amazon.

Hoary Mountain Mint

P. incanum, also known as hoary mountain mint, is native to the eastern US where it grows in dry to medium moisture conditions, in full sun or part shade.

This perennial reaches two to three feet tall and has a three to four foot spread.

P. incanum has silvery white bracts and upper leaves, giving the whole plant a brilliant, silvery white appearance. Flower clusters are white or white and lavender, and appear at terminal and upper leaf axils.

This is a good choice for Zones 4 to 8 if you like the looks of P. muticum but need something for dryer conditions.

You can purchase 0.16-ounce packs of P. incanum seeds from Roundstone Native Seeds LLC via Amazon.

Slender Mountain Mint

P. tenuifolium, more commonly known as narrow leaf or slender mountain mint, reaches two to three feet tall and wide.

As its common names suggest, it has thin, needle-like leaves, with clusters of small white flowers at the ends of the stems.

Recommended for Zones 4 to 8, it grows in full sun to part shade, in dry to medium moist soils, and has a wide native range, throughout eastern North America.

You’ll find P. tenuifolium seeds in packs of 0.16-ounces from Roundstone Native Seeds LLC via Amazon.

Virginia Mountain Mint

Native to eastern North America, Virginia mountain mint (P. virginianium) requires full sun and moderate moisture.

This species has narrow, tapering leaves with smooth margins, and clusters of small white flowers at the ends of the stems.

It reaches two to three feet tall and one to one and a half feet wide, growing in Zones 3 to 7.

You’ll find P. virginianium seeds in an assortment of pack sizes from Everwilde Farms via Amazon.

Managing Pests and Disease

Mountain mint is not much bothered by pests or diseases, and it’s even resistant to deer, gophers, voles, and rabbits.

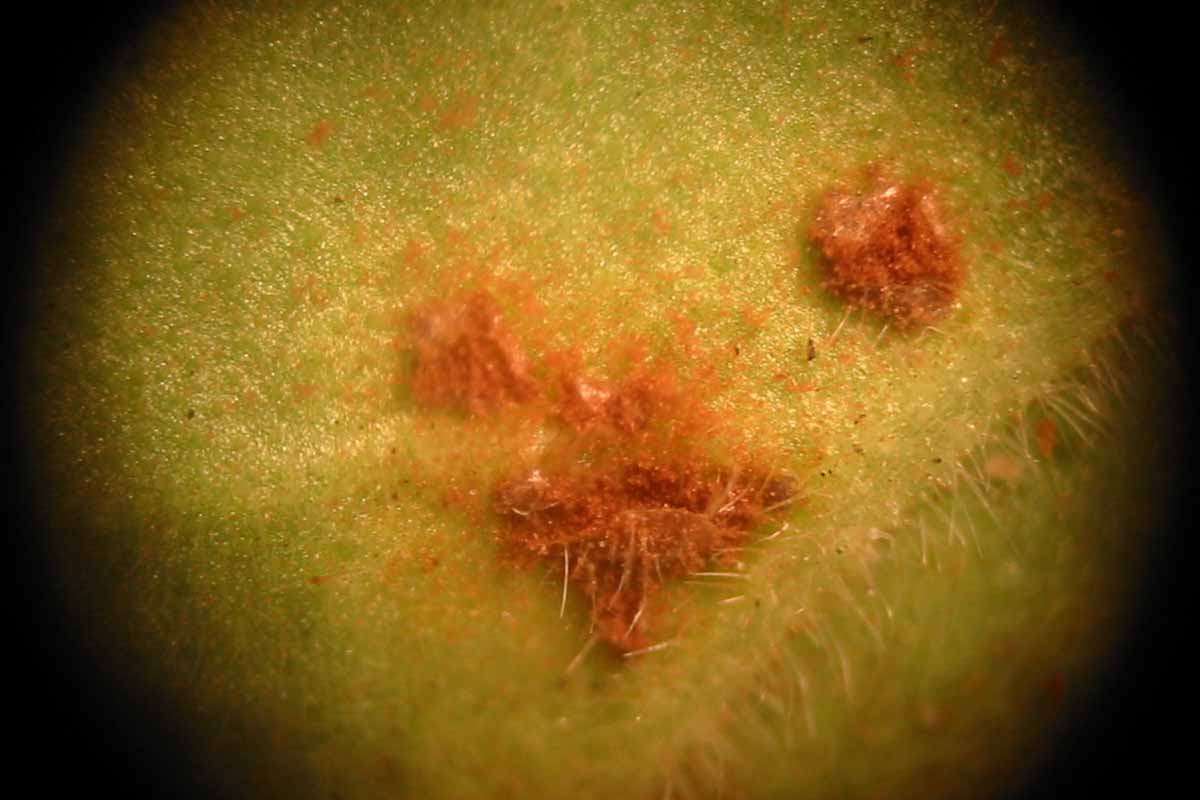

The only disease which tends to affect this plant is rust, which is more of a problem when the plant is in stressful conditions, such as during times of drought or right after transplanting.

Called “rust” because of the appearance it has on plants, this is a fungal disease that produces powdery, reddish orange spores on foliage.

You can prevent this fungal issue by avoiding conditions that will allow it to thrive. Space plants properly and avoid watering late in the day – water in the morning instead.

If rust has appeared on your Pycnanthemum specimen, and is not widespread, you can remove the affected foliage.

However, if rust is present on most of the plant, cut the foliage back to the ground and allow the plant to resprout.

Best Uses for Mountain Mint

It’s not hard to find a good use for mountain mint in the landscape!

Aesthetically, it will blend in perfectly with cottage gardens, herb gardens, edible gardens, and borders.

You can also let it naturalize in open woodlands or meadows.

As for landscape design, P. muticum creates an eye-catching, bright spot with its silvery white bracts.

Choose a type native to your location to grow with native wildflowers.

If you’re gardening for wildlife, remember that these plants have special value to bees, including honeybees, bumblebees, and other types of native bees.

Butterflies, and predatory and parasitoid insects also love Pycnanthemum species!

And while it’s noble to think of our insect neighbors – don’t forget to enjoy some for yourself as well – their leaves and flowers can be used to make invigoratingly minty herbal teas.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Herbaceous perennial | Flower/Foliage Color: | White, pink, lavender, blue /green leaves, silver bracts |

| Native to: | North America | Maintenance: | Low |

| Hardiness (USDA Zone): | 4-8 | Tolerance: | Drought |

| Bloom Time: | Summer | Soil Type: | Rich in organic matter |

| Exposure: | Full sun, part shade | Soil pH: | 6.1-7.3 |

| Time to Maturity: | 3 months | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Planting Depth: | Surface sow (seeds), top of root ball level with soil (transplants) | Attracts: | Bees, butterflies, hoverflies, pollinators |

| Spacing: | 1-3 feet | Uses: | Bee gardens, borders, butterfly gardens, cottage gardens, edible gardens, erosion control, herb gardens, insectaries, meadows, native gardens, naturalizing, pollinator gardens |

| Height: | 1-3 feet | Order: | Lamiales |

| Spread: | 1-3 feet | Family: | Lamiaceae |

| Water Needs: | Moderate | Genus: | Pycnanthemum |

| Common Disease: | Rust | Species: | Incanum , muticum, tenuifolium, verticillatum, virginianium |

Mounds of Silver Are Pollinator Gold

Now that you know just how to grow this fragrant plant, you’ll soon be ready to sit back and enjoy those silvery flowers and watch a parade of pollinators pass by!

Are you growing mountain mint – and if so, which type? Have you started counting pollinator visitors yet, perhaps with the help of a citizen scientist app? Let us know in the comments section below!

Care to delve into more mint growing info? We have more knowledge for you right here: