Alkekengi officinarum

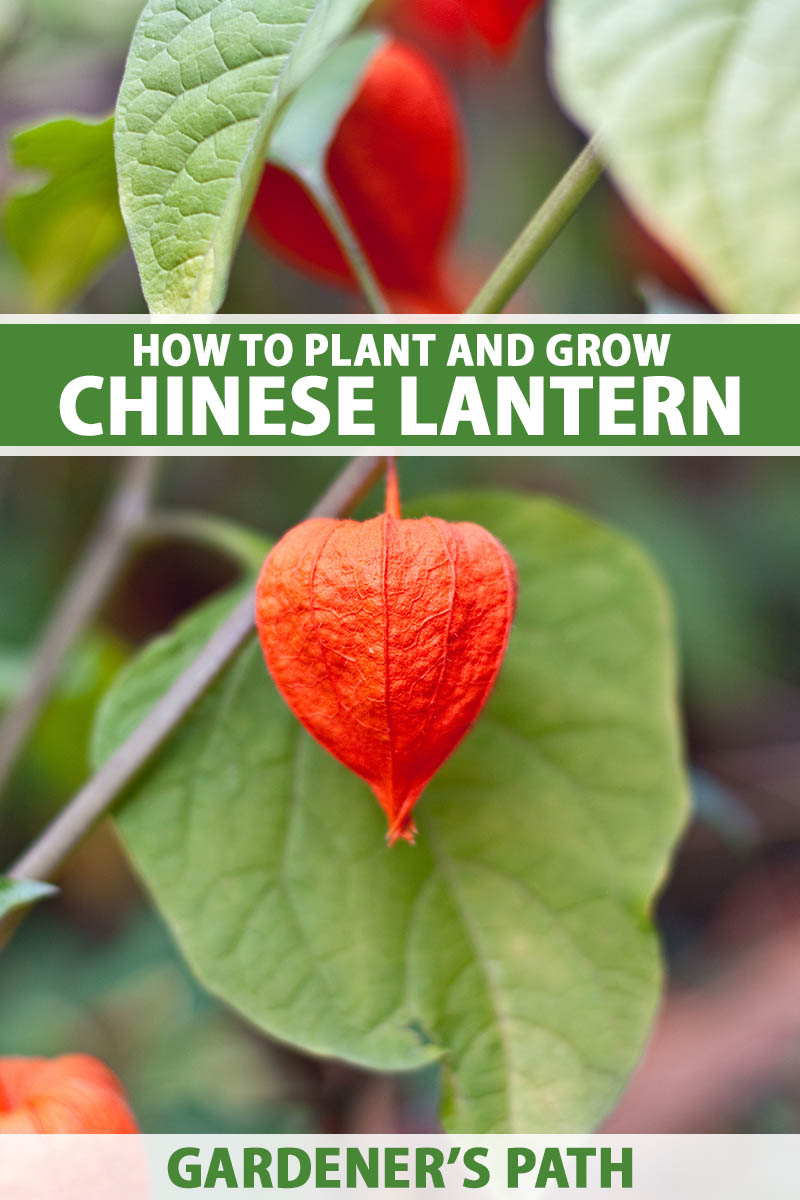

Chinese lantern is a charming ornamental plant that can bring a touch of whimsy to your garden, with its delicate red-orange husks.

Whether you grow it as a curiosity, or with the intention of using its stems for colorful autumn bouquets, this perennial will provide an unexpected source of bright fall color.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

Ready for a sneak peek? Here’s what we’ll cover:

What You’ll Learn

Before we get started, a bit of clarification is in order.

Don’t confuse this “Chinese lantern” with two other plants that go by the same common name, Abutilon pictum and Sandersonia aurantiaca.

A. abutilon is an understory tree that belongs to the mallow family, and S. aurantiaca is a perennial covered with yellow flowers that is more often called “Chinese lantern lily.”

The subject of this article, on the other hand, is a small, deciduous herbaceous plant known for its papery, red-orange husks.

Cultivation and History

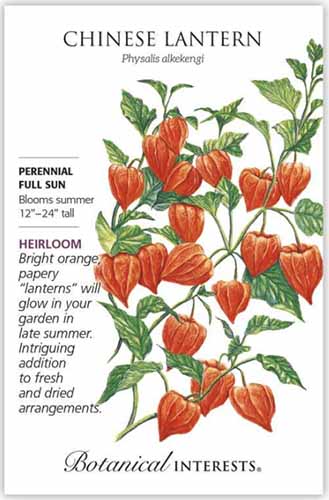

Alkekengi officinarum, or as it is commonly known, “Chinese lantern,” is an herbaceous perennial that is hardy in USDA Zones 3 to 9.

It was formerly known as Physalis alkekengi but has been reclassified – we’ll get to that story in a bit – and it bears a strong family resemblance to its relatives in the Physalis genus, ground cherry and tomatillo.

A member of the nightshade or Solanaceae family, Chinese lantern is also related to petunias, tomatoes, eggplants, peppers, and potatoes.

Like ground cherry and tomatillo, Chinese lantern grows its fruits enclosed within papery calyxes or husks.

Before we get to the star of the show, the husks, let’s have a look at the other features of this deciduous plant so that you’ll know what to expect.

Chinese lantern has alternate medium green leaves that are approximately three inches long. This perennial grows to be approximately 30 inches tall with a spread of two to three feet.

Its flowers are inconspicuous – they are small, yellowish white, and star-shaped.

The true visual interest in this species starts when those little white flowers begin their transformation into fruits.

Small green husks begin to grow, and within them, small fruits start to mature, hidden from view.

In late summer or early fall, the plant’s husks will turn from green to a bright reddish orange hue, giving them the appearance of miniature red paper lanterns – the inspiration behind the Chinese lantern’s common name.

The fruits inside remain hidden until the calyxes begin to disintegrate in winter.

As the husk decomposes, it leaves behind a fine latticework, revealing a brightly colored red-orange “cherry” inside, which gives this plant another of its common names, “love in a cage.” This small, round fruit is approximately a half an inch in diameter.

Chinese lantern has many other common names as well, and it is also known as “strawberry tomato,” “strawberry ground cherry,” and “Japanese lantern.”

Its former genus name, Physalis, comes from the Greek word for “bladder,” referring to the shape of its calyxes, and giving rise to another common name, “bladder cherry.”

Also called “winter cherry” and “winter lantern,” its calyx-covered stems can be dried for use in bright bouquets to be enjoyed during the autumn and winter seasons.

A native of Europe and Asia, the first known record of Chinese lantern appears in a book called the Codex Aniciae Julianae, otherwise known as the Codex Vindobonenis.

This codex is a manuscript on medicinal plants created in the sixth century, in which our subject is called simply “physalis,” from the Greek word for “bladder.”

It’s a bit ironic that bladder cherry was the original “physalis,” because it has now been booted out of the genus of the same name. While it was previously classified as Physalis alkekengi, its preferred new classification was changed to Alkekengi officinarum in 2012 after a genetic analysis of Chinese lantern and its relatives.

Not all sources have adopted this new classification yet, so you’ll often still see it called P. alkekengi. It’s sometimes referred to as P. franchetii, as well.

Although it is primarily grown as an ornamental these days, A. officinarum appeared in the Codex Aniciae Julianae for a reason – the author, Dioscorides, considered it to be a medicinal plant.

Over the long history of its medicinal use, bladder cherry fruits have been employed for treating kidney stones and other urinary ailments.

A Note of Caution:

While the small, round fruits of this bladder cherry are edible when fully ripe, unripe fruits as well as the other parts of the plant are considered highly toxic if ingested.

Medicinal uses aside, the fruit is reported as tasting either completely bland or exceedingly acidic.

Whether you plan to use A. officinarum as an ornamental plant or a medicinal one, be aware that it naturalizes easily, spreading via underground rhizomes, and is considered invasive in some areas.

If you’re concerned about winter cherry’s ability to spread, I’ll cover tips on keeping it contained in the maintenance section below.

Propagation

Chinese lantern can be propagated either by sowing seeds, or by dividing rhizomes to start new plants. Let’s discuss growing from seed first.

From Seed

If you’re growing winter cherry from seed, you can either sow the seeds directly into your soil, or start your seedlings indoors and set them out after your last frost.

If you decide to start them indoors for later transplanting, time your seed sowing for six to eight weeks prior to your last spring frost. You can start Chinese lantern in the same way that you would start annuals indoors – read more about this process in our guide.

To sow directly into your garden, wait until all danger of frost has passed in spring. While mature specimens are cold hardy, young seedlings are more vulnerable to cold weather.

Also make sure your soil has warmed to 65 to 75°F, for successful germination. A soil thermometer can be used to monitor the temperature of your soil and find the best moment for sowing your seeds.

Choose a location in full sun with well-draining soil. Prepare your soil by loosening it to about six to eight inches deep, and then working in some compost if desired.

Spray your soil gently with your gardening hose so that the surface is moist prior to sowing.

Sow a group of three seeds every 18 to 24 inches.

Light is required for germination of these seeds, so either sow on the surface of the soil or cover only very lightly, with about 1/4 of an inch of soil.

Press the seeds into the earth to ensure good contact, and then water in gently.

Be patient – seedlings may take up to 21 days to emerge.

Water the germinating seeds and young seedlings daily if there’s no rain, and continue to water as plants grow and get established.

Once seedlings are four inches tall, thin down to one plant every 18 to 24 inches.

If you have started seedlings indoors, about a week before your last frost date, harden them off before transplanting them to their outdoor location.

To do this, place the seedlings outdoors in a protected location during the day for about an hour. The next day, increase the amount of time to two hours. Over the next several days, leave the seedlings outdoors for longer periods of time and expose them to more direct sunlight.

After about a week of this transition, your seedlings will be ready to transplant – just make sure to wait until your weather forecast is clear of frost.

When propagating bladder cherry from seeds, some plants may flower and produce their colorful husk-enclosed fruits in their first growing season, while others may require an additional year of growth.

By Division

The best time to divide your winter cherry is in spring, when there’s some green growth that’s started already.

Choose a stem and follow it down to the soil. Using a hand shovel or hori hori knife, work out a clump of the rhizomes with the stem or stems still attached.

You can relocate this clump to a new garden location, or grow it in a container. If possible, perform this operation late in the afternoon or on a cloudy day so that the plant can have some time to recover out of the intense midday sun.

To plant your divided clump into the soil, dig a hole twice as large and deep as the roots. Loosen the removed soil and place some of it back into the hole.

Place the plant’s roots into the hole, making sure the crown is neither too deep nor too high, but sits just at soil level. Backfill with soil and water in well.

How to Grow

Colorful love in a cage can grow without pampering, thus its ability to outgrow its intended bed. However, when you want to ensure that you have the most beautiful autumn bouquets, it helps to follow a few growing tips.

Sun

Bladder cherry grows best in full sun but can tolerate partial shade as well.

Just be sure that these plants receive at least six hours a day of sunlight. A bit of shade in the heat of the afternoon would be ideal, particularly if your summers are extremely hot.

Soil

As for soil, Chinese lantern does best in moderately rich, well-drained soil. If you’re starting with poor soil, simply work some compost into it before planting. You won’t need additional fertilizer.

These plants grow well in soil that is slightly acidic to slightly alkaline. If you aren’t sure what type of soil you have, consider having your soil tested.

Water

Bladder cherry likes soil that is moderately moist. While plants are getting established, they will need at least one inch of water per week. Water thoroughly and deeply rather than lightly and more frequently.

As you strive to keep your soil evenly moist, be careful not to let conditions turn soggy, which could encourage disease spread.

And if your soil tends to dry out, consider adding a layer of mulch as a means of conserving moisture.

Growing Tips

- Grow in full sun to part shade.

- Provide well-drained soil and moderate water.

- Mulch to conserve moisture.

Maintenance

Maintenance of these plants is simple: provide water during dry spells, divide as needed, and above all, contain them if conditions in your area allow them to become invasive.

Containment

The trickiest part of maintaining Chinese lantern may be simply containing it, since this hardy perennial can spread via underground rhizomes.

If you have an area dedicated to your bladder cherry where you don’t mind it expanding from a clump into a small thicket, you can let it spread.

Otherwise, you may want to confine it to a container, such as a terra cotta pot, a window box, or your favorite planter.

If you decide to prevent unwanted spread by relegating your winter cherry to your container garden, place the pot in a sunny location where you’ll remember to water it. It will require more frequent watering in a pot compared with one that’s growing in the ground.

Alternatively, you can plant your bladder cherries in a plain nursery pot and sink the pot into the ground. However, this method isn’t entirely foolproof since rhizomes may escape through the drainage holes in the pot.

Yet another option would be to grow your Chinese lantern in a self-contained area, such as the green space between the street and the sidewalk, where it will be more manageable.

And be aware that rhizomes are not the only option with which these plants can spread. If you leave the fruit-filled husks on your Chinese lanterns over the winter, the dried fruit can fall, or be eaten by birds, and their seeds can be dispersed, creating additional volunteers in your yard.

If you’re concerned about it spreading in your area in this way, make sure to remove the fruits before the seeds can fully mature, dry, and be dispersed.

Where to Buy

There aren’t many cultivated varieties of bladder cherry, perhaps because the species itself is quite unique in its natural state.

In fact, this perennial species has such ornamental value that it won the Royal Horticultural Society’s Award of Garden Merit.

If you’d like to try your hand at growing this award winner, you can find Chinese lantern seeds for purchase in 150-milligram packs at Botanical Interests.

Chinese Lantern Three Pack of Live Plants

On the other hand, if you’d like to skip the seed starting part, you’ll find a three-pack of live plants from Spring Hill Nurseries available via Home Depot.

Managing Pests and Disease

Along with its unique and colorful, berry-enclosed husks, love in a cage has another advantage – deer tend to leave it alone. And it’s not much of a target for diseases or other pests, either.

If you do encounter a problem of this nature, here’s what to be on the lookout for:

Insects

This member of the nightshade family can attract some of the same insects that will feast on your tomatoes and eggplant. Some of the most common pests you’ll be likely to find munching on these plants are aphids, cutworms, and flea beetles.

Aphids

Aphids are miniscule insects that can be found on a wide range of garden plants. They tend to populate the undersides of leaves, where they suck valuable nutrients from the plants, weakening them and preventing them from thriving.

Minor infestations of aphids can often be removed with a blast or two from your garden hose.

Another way to keep aphid populations in check is by attracting beneficial insects such as ladybugs and green lacewings, both of which are predatory insects that prey on aphids.

For a thorough look at controlling aphids, make sure you read our dedicated article.

Cutworms

If your young bladder cherries are visited by a cutworm, this pest will likely leave its calling card – a seedling whose stem has been lopped off close to the base, with the remainder of the toppled plant left uneaten.

Cutworms aren’t true worms but are actually caterpillars, larval moths that are up to an inch and a half long, and they can be brown, gray, white, or greenish in color.

There are many different types of cutworms and they can damage garden plants in different ways. But in this case, your biggest cutworm threat will occur when your plants are still tender-stemmed seedlings.

Primarily a problem in the spring, cutworms hide in the soil or under vegetation during the day, coming out at night to do their damage. These larvae are a particular danger to young seedlings, since it’s impossible for the plant to recover once one eats through the still-tender stem.

You can prevent cutworm damage by placing collars around young seedlings to protect them. An empty toilet paper roll can serve as a collar – just place it around the seedling, and bury it a couple of inches deep in the soil.

By the time the toilet paper roll begins to decompose, your seedling should have a tougher, cutworm-proof stem.

It’s also wise to enlist some allies to reduce the overall populations of cutworms in your garden.

Birds such as robins can be helpful at controlling these pests, so offer them places to perch and scan your garden for tasty cutworm treats.

And parasitic wasps will also target cutworms, so attract them to your garden with some of their favorite plants – cilantro, dill, and cosmos.

Read our complete guide to cutworm control here.

Flea Beetles

Flea beetle damage is easy to recognize – these tiny insects chew small, round holes or pits in the leaves of your plants.

There are different types of flea beetles, so color may not be the most relevant descriptor.

Instead, they can often be recognized by their size – most of them are no bigger than an eighth of an inch long. They are also particularly good at jumping away from you when you try to pick one up to inspect it.

The use of row covers is one available method for keeping these pests off your Chinese lantern crop. You can read more about managing flea beetle infestations in our guide.

Disease

While Chinese lanterns are fairly disease resistant, even the toughest plants sometimes get sick. Here are some of the most common problems:

Alternaria Leaf Spot

Alternaria leaf spot is a fungal disease. It is recognizable by small lesions on leaves and stems. These lesions tend to be gray, brown, or tan, ringed with yellow.

This disease can affect not only bladder cherry but many other garden plants as well, including turnips, cauliflower, and kale.

Wet leaves and crowded plants make conditions more favorable for the fungi that cause this disease, so to protect your plant, water at the soil level instead of watering overhead, and make sure plants are spaced properly.

If the disease appears on your Chinese lantern, to prevent its spread, remove affected plant material, and then be sure to wash your hands and tools before handling other plants.

To treat Alternaria leaf spot organically, use a product such as neem oil.

However, do be aware that neem oil is not only a fungicide, but also an organic pesticide which can harm beneficial insects. Use it sparingly, according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

You’ll find Monterey neem oil available for purchase at Arbico Organics.

Damping Off

Another fungal disease, damping off causes young seedlings to suddenly wither and die.

Since there is no way to bring back seedlings that succumb to damping off, prevention is imperative.

Successfully preventing this frustrating disease comes down to using best practices when sowing your seeds. Read our article about preventing damping off to learn more.

Powdery Mildew

Powdery mildew is a fungal disease caused by not just one, but hundreds of different species of fungi.

The telltale signs of this disease include leaves that look as though they’ve been dusted with a grayish-white powder.

The fungi responsible for this disease suck valuable nutrients from plants, weakening them, and often causing wilting and distorted leaves.

To learn more about preventing this disease with a selection of homemade and organic remedies for fighting powdery mildew as well, be sure to read our article.

Best Uses

Although the fruits of bladder cherry do have a history of medicinal use and they are safe to consume when ripe, though very sour, you can also reserve this plant for strictly ornamental use.

In your landscape you might use Chinese lantern as a border or in a flower bed.

Or include it as a perennial member of your cottage garden, combined with purple or blue New England asters, and white Montauk daisies, which share similar growing requirements, and will both be in flower when this orange husk cherry is coming into its full glory.

Keep in mind that love in a cage will be showing off its bright orange color in late summer or early fall, so it would be the perfect perennial to include in your plans for a spooky Halloween garden too, or a cozy autumnal garden display.

Bladder cherry is an excellent choice as a cold temperature ornamental for the fall garden and would provide a nice textural contrast to late season chrysanthemums.

And if you decide to leave the lanterns on the plant rather than harvesting them, it can also provide bright splashes of color through the doldrums of winter.

Of course, if you do decide to harvest the husk-covered branches, you will have no scarcity of options in incorporating them into either fresh bouquets or dried flower arrangements.

You might even choose to take its common name quite literally and hang a branch or two over your fairy garden, as miniature lanterns.

Alternatively, you can use them right away and let them dry in a vase, or work them into a festive autumnal wreath.

When harvesting these ornamentals to use for flower arrangements, you have options as to when you should collect the branches.

Some gardeners prefer to let all the husks on a branch mature to a deep reddish-orange hue. Others prefer to have a gradation of colors on a single stem, ranging from deep orange to green.

Whichever you choose, cut the stems back close to the ground, and remove the leaves as well as any damaged husks.

For dried arrangements, you can either hang the stems upside down, or dry them with their calyxes hanging down, naturally. In either case, allow them to dry in a cool, dark place.

Dried Chinese lanterns will retain their color for a few years if kept out of direct sun.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Deciduous perennial | Flower / Foliage Color: | Tiny white flowers, large orange-red calyxes |

| Native to: | Europe, Asia | Maintenance: | Low |

| Hardiness (USDA Zone): | 3-9 | Tolerance: | Cold hardy once mature |

| Bloom Time: | Late summer-early fall | Soil Type: | Sand, loam, and clay with plenty of organic material |

| Exposure: | Full sun, partial shade | Soil pH: | 6.1-7.8 |

| Spacing: | 18-24 inches | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Planting Depth: | 1/4 inch (seeds) | Attracts: | Bees |

| Height: | 30 inches | Companion Planting: | Bachelor’s buttons, coneflower, Montauk daisy, New England aster, purple aster |

| Spread: | 1-2 feet | Uses: | Ornamental, dried flower arrangements, cut flower arrangements |

| Time to Maturity: | 2 years | Family: | Solanaceae |

| Water Needs: | Moderate | Genus: | Alkekengi |

| Common Pests and Disease: | Aphids, cutworms, flea beetles, slugs, whiteflies; Alternaria leaf spot, black rot, damping off, powdery mildew | Species: | Officinarum |

Light Up Your Garden with Chinese Lantern

With Chinese lantern, you’ll have a unique perennial that will offer you branches dangling with colorful, papery husks to enjoy in autumn and winter.

Have you grown love in a cage before? What is your favorite way to use the brightly colored husks? Let us know in the comments section below.

Interested in some companion plants for your winter cherry? Here are some additional flowering perennials that will grow in the same conditions and show off their color at the same time:

Why are we encouraging an invasive plant?

Hi Randy, That’s a good question! I totally understand your concern as a gardener that has done a lot of studies on landscaping with native plants and who prioritizes native plants in my own landscapes. Many of our readers are located in North America, but on the other hand, many of them are not – we have readers located all around the world! That means for some people reading this article, this plant is actually native to their location. For readers who want to know more about the invasive potential of this plant, I’m linking to a world map that… Read more »

Question: My Chinese lantern has never turned orange or red. The pods remain green throughout the growing season. Any advice?

Hi Sharon, You didn’t mention your location or USDA hardiness region, but I’m guessing your season isn’t long enough for these fruits to come to full maturity. You could try growing some from seed indoors and then transplanting them out to add some time to your growing season, but this technique doesn’t always work. That’s because those of us with short growing seasons still don’t necessarily have enough warm days for certain plants to reach maturity.

How common are these in the U.S? specifically Minnesota. We had a bunch of these pop up on our property. Thank you.

Hi Mark, There are a few Physalis species that are native to Minnesota and which look fairly similar. You may want to compare your plants with photos of species such as Clammy ground cherry, Virginia ground cherry, and Long leaf ground cherry just to make sure you have made a correct ID of the plants on your property. As to whether this species is invasive in Minnesota, a quick search tells me its not on the invasive plants list for that state. However, if a former inhabitant or neighbor has been growing Chinese lantern, that could explain why you’re seeing… Read more »

I’ve had Chinese lanterns in pots in northwestern Ohio for 3-4 years. Last year they didn’t bloom. I thought perhaps they were overcrowded so I separated them and gave some to my neighbor and some to my daughter in Maryland. They both planted them in large containers. None of the plants bloomed for any of us this year. I haven’t been able to locate any info online as to why they may have stopped blooming.

Hi Debbie, There could be a few reasons causing your plants to fail to bloom. I’ll throw out some ideas and you can see if any of these sound like they might be the cause. – Too much fertilizer can cause the plant to produce more foliage but prevent it from flowering. Did you start applying a different type of fertilizer by chance? – Lack of sunlight is another reason these plants could fail to produce flowers. Sometimes sun and shade conditions change over time (as nearby trees get bigger, for instance). Since it happens gradually we might not notice… Read more »

Does anyone know how to tell when the seeds are ripe? Right now (mid-Oct in zone 3 the bright red berries have white seeds inside. Are these viable? Thanks.

Hi Renee,

If the fruits are falling off the plants on their own, the seeds inside them will be ripe.

Hope this helps!

Hi, I live in central PA and gave grown these plants – they flower, turn green , never turn orange before they dry into little cages around a red fruit. What is the problem here?

Hi Nancy,

Thanks for your comment. If I understand you correctly, you’re saying that the fruit inside is ripening to red, but the husk never develops its orange hue in autumn, is that correct? This may be due to hotter and longer than normal summers transitioning quickly into winter-like weather. The plant may be missing its cue to produce those colorful husks.

You might try growing them in part shade and see if that helps.

Let us know how it goes!