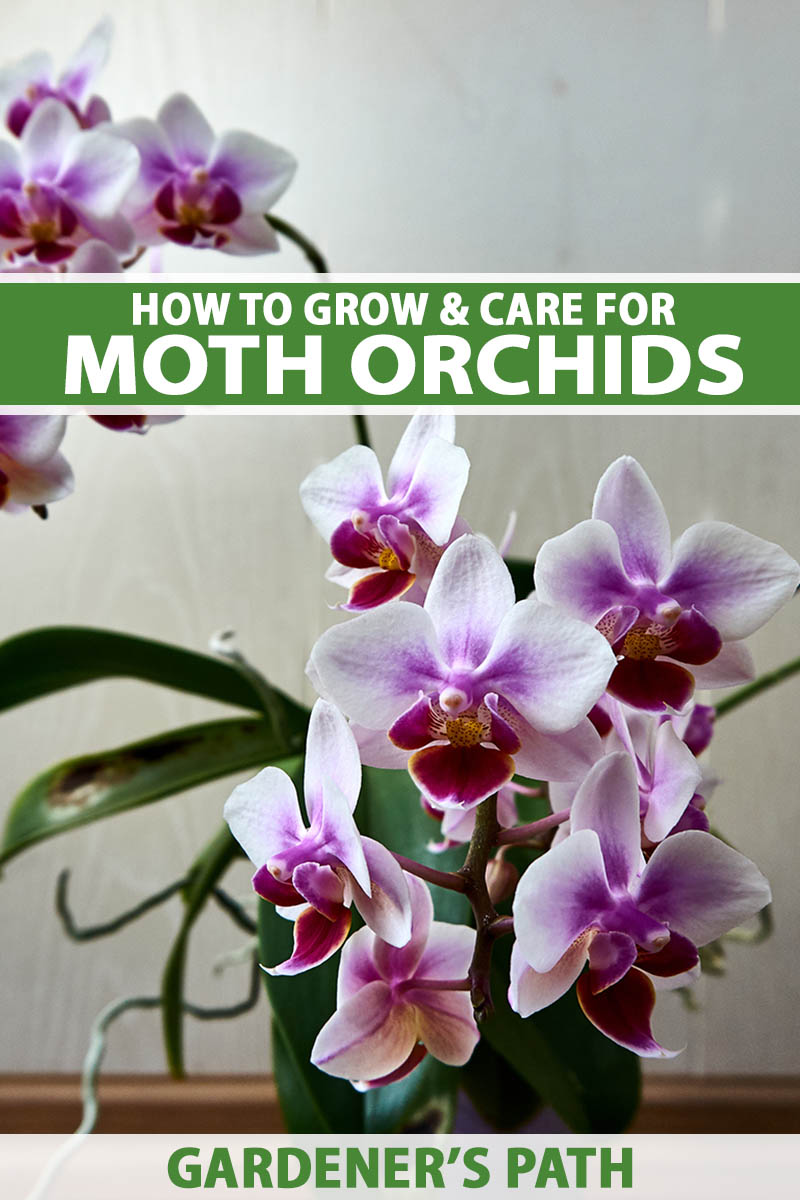

Phalaenopsis spp.

I buy cut flowers for myself every few weeks because the colors and textures cheer me up every time I look at them.

It’s a little bit of nature that I can enjoy inside my home. But a tiny part of me cringes at how much it costs to bring home all these flowers that will just end up being tossed out in a few days.

This is why – especially in the winter – I find myself bringing home Phalaenopsis orchids.

They cost about the same amount as a big bouquet, plus a decorative pot is usually included, and the display can last for months.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

Also known as moth orchids because the flowers resemble dozens of moths flitting around the leaves, these common plants are less challenging to grow than other orchid species, and they’re every bit as elegant as that pricey bouquet that you’ll just be tossing out soon.

These plants can provide a show for years to come.

Whether you were gifted an orchid and aren’t sure how to make it happy, or you’re an experienced grower looking for some help, this guide covers it all.

Here’s what we’ll chat about, coming right up:

What You’ll Learn

When I started out with houseplants, I was intimidated by orchids.

They seem so delicate and strange – how on earth do you keep them alive, let alone help them to thrive?

Years later, friends now bring me their orchids to help them recover and rebloom.

What Are Moth Orchids?

Phalaenopsis comes from the Greek “phala” for moth and “opsis” meaning appearance.

Some species growing in the wild truly look like a cluster of moths flitting around near a tree, so these are well-named.

There are multiple subgenera within the Phalaenopsis genus, and this genus includes some of the most popular cultivated orchids.

The subgenera you may come across are Phalaenopsis, Parishianae, Aphyllae, Proboscidioides, and Braceana. The first two of these contain the vast majority of plants that you’ll find in commercial cultivation.

These plants may be found throughout tropical Asia, as far west as India and Nepal, and as far east as Papua New Guinea.

They grow in the wild as far south as tropical Australia and north to Taiwan. And they grow at every elevation, from sea level to thousands of feet up.

Almost all moth orchids are epiphytes, which means they grow on the branches and trunks of trees.

They pull nutrients and water from the air as well as the debris that has collected on the phorophyte – or host plant – that it is growing on. Some, however, are lithophytes, which are plants that grow on rocks.

That might seem like an unimportant distinction, but when it comes to providing the right water, light, and growing medium, you’ll be miles ahead if you understand the conditions in which these plants have evolved to grow successfully.

All of these plants have succulent leaves that emerge from a central point, and exhibit long-lasting flowers.

They bloom on flower stalks and most typically start blooming in late summer through winter or early spring. All of the flowers open at once.

Cultivation and History

Moth orchids were first identified by Westerners in 1750, but the first plant in cultivation didn’t reach European shores until nearly 100 years later, when naturalist and noted collector of wildlife Hugh Cuming sent one that he located in Manila to England.

Now, they’re incredibly popular and can be found available for purchase everywhere from specialty nurseries to the neighborhood grocery store.

Moth Orchid Propagation

The medium that you use is important when you’re propagating Phalaenopsis.

You can’t use standard potting soil – it’s too dense. Well, you can use it, but you’ll make your life much more difficult than it needs to be!

Chopped fir bark is the best medium. The pieces should be around a quarter-inch to an eighth of an inch in size.

To that, you can add a little perlite and charcoal if you desire, but it’s not necessary. Perlite retains water and improves drainage, and charcoal absorbs excess water.

Have you used charcoal in gardening before?

I have sworn by the stuff for growing plants that are prone to root rot ever since I had an extremely sick plant that was rotted down to just one main root about an inch long.

I thought for sure it was a goner, but I added lots of charcoal and after about six months it had fully recovered and sent out new growth, including a ton of new roots.

It’s fairly affordable, too. Grab a 24-ounce bag of horticultural charcoal from Perfect Plants Nursery or at Amazon.

You can also buy pre-made products that contain a similar mix to what I’ve described above.

These mixes are formulated with the proper pH for Phalaenopsis, somewhere between 5.5 and 6.0.

Miracle-Gro has a mix made especially for orchids that you might like to use. It comes in eight-quart bags that are available for purchase from Amazon.

From Seed

If you have more than one moth orchid, you can use a paintbrush to take the pollen from one flower’s column and place it on another flower’s stigma.

Care for your hand-pollinated plant as you normally would, and in about nine months or so, a seed pod will form.

At that point, many orchid breeders will send the pod to a special lab to undergo a process known as flasking, which entails germinating the tiny seeds in a flask filled with a gelling agent and symbiotic mycorrhizal fungi.

You can try germinating your seeds at home, but it’s extraordinarily difficult with a low rate of success.

If you were to give it a go, you’d need a sterile environment, agar gel supplemented with nutrients, hydrogen peroxide to clean the seeds, and small flasks to start the seeds in.

You can learn all about this process in our orchid seed propagation guide.

If you send the seeds you’ve collected out, the lab will return seedlings upon successful germination that you can transplant and raise.

I’d strongly encourage you to send your seeds out if you are creating a unique hybrid and need to ensure success. That’s what most serious growers do and it’s well worth the fees involved, which are generally low.

From Divisions

As Phalaenopsis plants grow, they become taller and put out lots of aerial roots.

These form near the base of the plant but above the potting medium. When your plant has lots of these aerial roots, you can divide it to create new plants.

Grab a sturdy, clean pair of clippers and fill a fresh pot with your chosen medium.

Cut the stem above the soil but below as many of the aerial roots as you can. Pot the top in the new container with the aerial roots buried in the medium.

You can treat the top cutting as you would any orchid, but the bottom part of the parent that remains needs special care.

Put it in a spot with bright, indirect light and water lightly. You want to keep the medium moist but it shouldn’t be wet.

If you give the roots too much water, they will rot, so picture the amount of water you normally give your plant and halve that.

If you’re careful to only water when the soil is nearly dry, you should see a bunch of new plantlets pop up after a month or two of care.

Detach these plantlets with some roots attached to each one, and pot them separately.

Keep watering and treating the bottom half as you normally would and it will regrow eventually.

You need to be careful not to overwater, though, because the plant will require less moisture than before.

From Seedlings

Whether you send your seeds out for flasking or you buy seedlings at a store, once you bring them home, you need to put them in a bark-based medium.

Young seedlings are usually shipped in agar gel or a similar medium.

Let’s talk about pots really quickly. You can technically grow an orchid in any old houseplant container – but I wouldn’t recommend it.

Plastic containers made specifically for orchids are available, with extra holes or slats cut into the bottom as well as up the sides.

Buy one of these and put it inside a decorative cachepot for good drainage and easy removal when watering.

To start, fill an extremely small pot with the bark mix described in the intro to this section. When I say small, we’re talking a one- or two-inch pot, if that.

The container should be the same size as the root ball. If it’s much larger you will run the risk of introducing root rot. The container should also have lots of drainage holes.

To repot seedlings, gently pull the plant out of the container and brush or wipe away the old medium.

Place the seedling in its new pot and hold it there. Then, tuck the medium in around the roots.

You might need to use a chopstick or something similar to tuck it into the nooks and crannies. Firm up the medium around the roots and water well – but not too well, to avoid oversaturation.

From Potted Nursery Plants/Transplanting

Most of the time when you buy an orchid at the store it will come in a plastic container with tons of drainage holes.

If that’s the case, you can just keep it in there until it’s time to upgrade to a larger pot. If you don’t like the look of the pot, feel free to place it inside a decorative one.

Sometimes, you can find orchid plugs or plants in solid grower’s pots with potting soil and maybe a few drainage holes in the bottom. If that’s the case, you’re going to want to repot your orchid ASAP.

First, make sure you have appropriate containers. You want to use something with lots of slits or holes for drainage.

You can buy a three-pack of six-inch clear pots that are perfect for the job at Amazon.

Grab some orchid bark from Amazon in a four-quart bag while you’re at it. I love Sun Bulb’s orchid mix, which contains charcoal, sponge rock, and fir bark.

Remove the orchid from its container and brush away as much of the media as you can from the roots.

Now, place the orchid in its new container and fill in around the roots with the orchid bark mix.

How to Grow Moth Orchids

Watering is arguably the biggest challenge with orchids. It’s so easy to overwater. That’s why many plants come in plastic pots filled with bark and with lots and lots of drainage holes.

Some people recommend watering with ice cubes once a week to ensure you’re giving the right amount of water.

I don’t think this method takes into account the change in humidity that happens in homes throughout the year. The ice can also damage any roots that it comes in direct contact with.

You want to add water when the substrate is almost entirely dry.

You can touch the substrate or use a soil moisture meter, though these are less reliable in a bark mix. Over time, it’s pretty easy to tell just by the weight of the plant whether or not yours is in need of irrigation.

Be sure to only water at the soil level and not on the leaves. Standing water on the leaves can cause crown rot.

You could also opt for bottom watering. If you live in a humid area, you’ll need to water far less often than gardeners in dry climates.

Light is less challenging to get right than moisture. These plants like bright but not direct light, except for a little in the morning.

Pick a north- or east-facing window, or a west- or south-facing window with a sheer curtain over it.

Err on the side of providing too little light rather than too much. These plants won’t thrive in bright direct light and the healthiest ones growing in the wild tend to be in shadier spots.

When it comes to temperature, aim for a warm environment during the day, with 80°F being ideal.

It can be about 15 degrees cooler at night, but that’s not necessary. They can survive brief periods with temperatures dipping down into the mid 30s, but try to avoid that.

Give your phal really good air circulation, and don’t put it in a closed spot.

Fertilizing

Feeding your orchids requires understanding which point of the growing phase your plants are in.

You must feed them to encourage new blossoms and you should support them during their long flowering phase.

The problem is that most people buy these plants while they’re blooming. Commercial growers encourage them to bloom outside their normal phase in order to encourage sales.

For that reason, I find it’s best to lay off the fertilizer after purchasing new plants for at least a month. It won’t hurt anything to underfeed for a short period, but overfeeding can lead to some problems that can be a challenge to remediate.

After that first month, feed plants once a month with a diluted or extremely mild fertilizer when the plant is in bloom.

Increase applications to feed every two weeks when the plant isn’t blooming, to help it build up nutrients to start the blooming cycle over again.

You should feed plants with a soilless substrate a bit more often, particularly if they’re mounted.

Dr. Earth’s Pump & Grow fertilizer is an excellent option.

Dr. Earth Pump & Grow Fertilizer

It’s mild enough for regular use and balanced to give your plants the nutrients they need. Bring home a 16-ounce bottle from Arbico Organics.

Generally, you should stick to feeding the roots. But if your plant is struggling or you’re dealing with root damage, go ahead and supplement temporarily with foliar feeding.

Use something specifically formulated for orchids, like Organic Orchid Food’s ready-to-spray foliar fertilizer. It’s available at Amazon in an eight-ounce container.

Growing Tips

- Place in bright, indirect sunlight.

- Water at the soil level, only when the potting medium is nearly dry.

- Feed every two weeks when plants aren’t in bloom, and once a month while blooming.

Maintenance

Orchids aren’t the most attractive plants when the flowers fade.

Snipping off that flower stalk can go a long way toward improving the appearance of your plant, and it encourages reblooming.

Just take a clean pair of scissors and snip the flower stalk as close to the base as you can.

You should repot once every year or two, but you don’t necessarily need to increase the pot size. The roots should be fairly compact.

This job should be done in the early summer after the blossoms have faded.

Pull the plant out of its container. There will likely be some roots that have crawled out of the drainage holes or above the surface of the soil.

A few are no big deal, but seeing a lot of them is a sign that you should go up a size with the container.

Don’t worry if you break a few of the roots as you repot. Just clean up any broken roots with a clean pair of clippers.

Loosen up the roots and remove all of the old medium. While you’re at it, wipe out the old pot if you’re reusing it, with a bit of soap and water.

Put the plant back in its container or in its new pot, and gently fill in around it with fresh orchid medium.

Blooming Again

It’s one of the biggest challenges of orchid growing to take a plant that has stopped blooming and encourage it to bloom again.

With moth orchids, the key is to provide about 15 degrees of difference in temperature from day to night. Temporarily aim to provide something slightly cooler than the plant’s usual conditions.

It should be around 55°F at night and 70°F max during the day until you see the flower spike start growing again.

Then move it back to a location with warmer temperatures closer to 80°F during the day and 15°F cooler at night.

White and pink-flowered types in particular need cooler temperatures to bloom again.

If your plant stopped blooming and you moved it to a cooler spot in the summer, you should start to see new flower spikes forming by about January in most regions and for most Phalaenopsis species.

Our general guide to encouraging orchids to rebloom has more tips.

Species to Select

Many times, these plants will just be listed as generic moth or Phalaenopsis orchids at grocery stores, big box stores, and nurseries.

For instance, Fast Growing Trees has a group of unspecified plants from the genus available in a 10-inch pot.

Though the species, hybrid, or cultivar isn’t described, you can choose between white, purple, salmon pink, or watercolor blue flowers. These are shipped while they’re in bloom.

But by the way, if you ever see orchids so vibrantly colored or in colors that just don’t seem to happen in nature, it’s best to trust that instinct.

Most are dyed with artificial coloring in these cases. When your orchid sends out a new flower spike if it’s one that’s been dyed for sale, the flowers will likely be white or pale pink.

There are many, many hybrids and there are always new ones popping up. Some of the more common hybrids are bred by Mituo.

Their Diamond series features flowers with some pretty striking patterns and colors.

Amabilis

The beautiful moon orchid, as this species is often called, is one of the varieties most commonly found in stores.

P. amabilis flowers are typically white or nearly white.

Each blossom can be up to four inches across and there can be dozens on a single plant. Each of these lasts for weeks, and the plant continually sends out new flowers all summer long.

The plants themselves can grow over three feet tall indoors with proper care.

Its size and beauty isn’t what makes P. amabilis so popular, though. It’s also forgiving of imperfect watering, and pest and disease resistant.

Amboinensis

This species is less common, but it’s highly sought-after on the market.

In their native habitat, P. amboinensis plants are endangered, but there are lots of lovely hybrids out there if you’re willing to do the work of finding them.

Most feature flowers with some combination of yellow, red, brown, or white petals. They’re also highly fragrant with a strong floral scent.

Plants can reach about a foot tall and each one can support multiple flowering stems at a time.

The red and white striped petals with pale yellow tips on ‘Nicole’ are particularly dramatic.

Aphrodite

This species has small white flowers, but there are some hybrids that feature pink splotches or ones with entirely pink petals.

Easily mistaken for P. amabilis, P. aphrodite flowers are about an inch smaller and pinkish-red at the base of the central petal. The plants are smaller overall, too.

Mannii

This species likes to do its best impression of a swarm of bees, with petite yellow and brown blossoms on plants that stay under a foot tall.

If you’re looking for a miniature orchid, see if you can find P. mannii ‘Black.’

It has tiny, bright yellow and brown flowers with dark black spots. They really look like bumblebees hovering around the tiny, six-inch-tall plant.

Schilleriana

Along with P. amabilis, this species represents some of the most popular flowers on the market.

P. schilleriana is super tolerant, doesn’t mind low light or some direct morning sun, and won’t collapse in a heap if you aren’t the best at watering.

The plants can be covered in dozens of small flowers in colors like white, pink, and lilac. They can grow up to three feet tall.

‘TKB’ is a popular choice. It has mottled green and grayish-green leaves that look good even when the plant isn’t in bloom.

But of course, when it is, it’s even more eye-catching. The pink flowers are bright and mildly fragrant.

Managing Pests and Disease

For the most part, if you water and feed your moth orchid appropriately, and you isolate any new plants to check for pests or signs of disease before bringing them into your home with the rest of the bunch, you probably won’t encounter too many problems.

If issues do occur, quick action is key.

Insects

Since we typically grow these indoors as houseplants, orchids may be attacked by some of the common critters that chomp on all houseplants.

Aphids

News at 11:00 – a plant that is attacked by aphids! I know, it’s shocking!

But really, most houseplants are subject to aphid infestation, so it’s no surprise.

There are dozens of species that might feed on your orchids, but green peach (Myzus persicae) and cotton aphids (Aphis gossypii) are a few of the most common.

It doesn’t really matter which species of these tiny little jerks are messing with your orchids, you can deal with them all the same way.

You can easily spray them off your orchid with a blast of water. Do this once a week for a few weeks and the problem should be handled.

Since orchids don’t have a lot of tiny leaves and branches, there are only a few places to look for these small sap-suckers, so that’s a plus.

If the old water method doesn’t work, we have a guide to help you eliminate aphids.

Mealybugs

Mealybugs are pests in the family Pseudococcidae.

These small pests use their sucking mouthparts to feed on the sap from the stems and leaves. They’re oval-shaped and white, cream, yellow, or pale pink.

If you see them, act right away. They can rapidly become a severe problem, and they can hide in the nooks and crannies of the bark in pots.

These pests can cause a plant to rapidly lose flowers, turn yellow, and die. Quickly isolate the infested plant and grab some rubbing alcohol and cotton swabs. Dab some alcohol on each bug.

Our guide to managing mealybug infestations has more tips that can help.

Disease

A fantastic thing about Phalaenopsis is that they show good resistance to disease.

If you keep them healthy with proper care, you probably won’t run into either of these ailments, but that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t be aware of potential issues.

Black Rot

If you start seeing black spots on the leaves of your plant, you should suspect black rot.

It’s caused by two different species of oomycetes or water molds, Pythium ultimum and Phytophthora cactorum.

More importantly, just be aware that this problem pops up when plants are overwatered or grown in overly humid conditions. These pathogens need lots of moisture to survive and reproduce.

You should always use clean tools and a sterile potting medium when working with your plants to prevent the spread of water molds and other pathogens.

On the bright side, Phalaenopsis orchids are less susceptible to this disease than some from other genera.

Treat your plant with a Bordeaux mixture and cut out any heavily infected parts with a clean knife.

And by the way, knowing how to make a Bordeaux mixture is a handy skill to have because it works against a lot of diseases.

This mixture combines one part copper sulfate, one part lime, and ten parts water.

Leaf Spot

The fungus Phyllosticta capitalensis causes a disease known as leaf spot. It causes tiny black speckles to appear all over the foliage.

Leaf spot won’t kill your plant, and Phalaenopsis orchids are less likely to contract this disease than plants from other genera, but it sure is ugly when it strikes.

I know it sounds strange, but if you paint the spots with dots of clear nail polish, this will “glue” the spores down and they won’t be able to spread.

Since the fungi won’t kill your plant and this disease is really difficult to get rid of, even with chemical treatment, this is the best way to deal with the problem.

Root Rot

Before you see leaf spot or black rot, you’ll likely see root rot. It’s the most common disease to impact orchids.

Technically, it’s not usually pathogenic, but it can be. It’s caused by chronic overwatering that drowns the roots.

The leaves will droop and turn pale, and eventually collapse. Meanwhile, the roots turn black and mushy.

Your best option to try to save the plant is to remove it from the pot and take it out of the growing substrate.

Let it dry out, wipe down the container to sanitize it, and repot in fresh substrate. Be sure to ensure good drainage, and avoid overwatering.

Best Uses for Moth Orchids

Many of us will stick an orchid in a pot and put it on a tabletop for display, and there’s nothing wrong with that. But there are other options!

Since they’re epiphytes, you can also grow them on the surface of a wood substrate wrapped in moss to create a really special display.

You can also eat orchid flowers. Use them to garnish a cocktail to wow your friends.

Just be sure to avoid using flowers that were in bloom when you purchased the plant, since you won’t be able to tell with certainty whether these were treated with chemicals or dyes.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Flowering evergreen epiphyte | Flower/Foliage Color: | White, pink, yellow, brown, orange/green |

| Native to: | Tropical Asia | Maintenance: | Moderate |

| Hardiness (USDA Zones): | 10-12 | Water Needs: | Moderate |

| Bloom Time: | Spring, summer, fall | Soil Type: | Loose bark |

| Exposure: | Bright indirect light | Soil pH: | 5.5-6.0 |

| Time to Maturity: | Up to 7 years | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Spacing: | 1 foot | Order: | Asparagales |

| Planting Depth: | Crown just above potting medium (transplants) | Family: | Orchidaceae |

| Height: | Up to 3 feet | Subfamily: | Epidendroideae |

| Spread: | Up to 1 foot | Genus: | Phalaenopsis |

| Common Pests and Diseases: | Aphids, mealybugs; black rot, leaf spot | Species: | Amabilis, amboinensis, aphrodite, mannii, schilleriana |

There’s Nothing Like Fantastic Phalaenopsis Orchids

They’re truly elegant plants, orchids. But they’re not like other houseplants. They need special treatment to grow and look their best.

But when they do, they’re true showstoppers. And now, you have all the details you need to make yours as lovely as possible.

Is this your first time growing an orchid? Have you run into any trouble? Did this guide help you sort things out? Let us know all about your adventures so far in the comments.

Want to learn more about growing orchids? Have a read of these guides next: