Kalanchoe spp.

There are many succulent plants that are hard to kill and easy to care for. And then there is kalanchoe.

Species in the Kalanchoe genus are both hardy and low-maintenance, but they also take the whole notion of “tough plant” up a couple of notches.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

Kalanchoes are members of the stonecrop family, aka Crassulaceae, along with other common succulents grown as houseplants like jade.

Not only do these plants thrive with benign neglect, but several types flower regularly, even indoors. Others are known for their foliage.

It’s quite simple to propagate new specimens too, either from seeds or cuttings.

And many species, like K. daigremontiana or “mother of thousands,” reproduce viviparously. These varieties grow bulbils, or wee baby plants, along the edges of their leaves.

The plantlets drop off to root in the soil near the base of the parent, or gardeners can gently dislodge them and place them elsewhere to start new plants.

Grown outdoors, kalanchoe can be a good ground cover option since it tolerates dry spells well once established.

Some types are superior to others for ground cover – one is the low-growing, spreading species commonly known as flapjacks, or K. luciae.

Another is the flower dust plant, K. pumila, which forms small shrublets with leaves that are white to pale pink in color and dusted with a powdery coating that looks like light frost. It will send up stalks in late winter that flower with tiny pink blooms.

Intrigued? I’d like to tell you a bit more about kalanchoes and give you a few tips on how to grow and care for them.

After all, even the most easygoing succulents have a few needs that must be met for them to thrive, and kalanchoe is no exception.

Here’s everything I’ll cover:

What You’ll Learn

Cultivation and History

Kalanchoe is a fun name, pronounced KAL-ən-KOH-ee or sometimes with a soft “ch,” as in ka-lən-chō, or with the hard “k” sound and the third syllable pronounced like the “ou” in ouch – ka-laŋ-kə-ee.

Native to Madagascar and other tropical parts of Africa, the Kalanchoe genus includes at least 120 species. Many of them are cultivated worldwide, but the majority are found only in their native range.

I mentioned before that these belong to the stonecrop family, and the stonecrop tag is accurate: All of the species in this genus are good candidates for rock gardens and can survive with minimal water and even through drought conditions.

They aren’t particularly cold-hardy though, and can only be grown as perennials outdoors in Zones 10 to 12, or sometimes in Zone 9, depending on the variety.

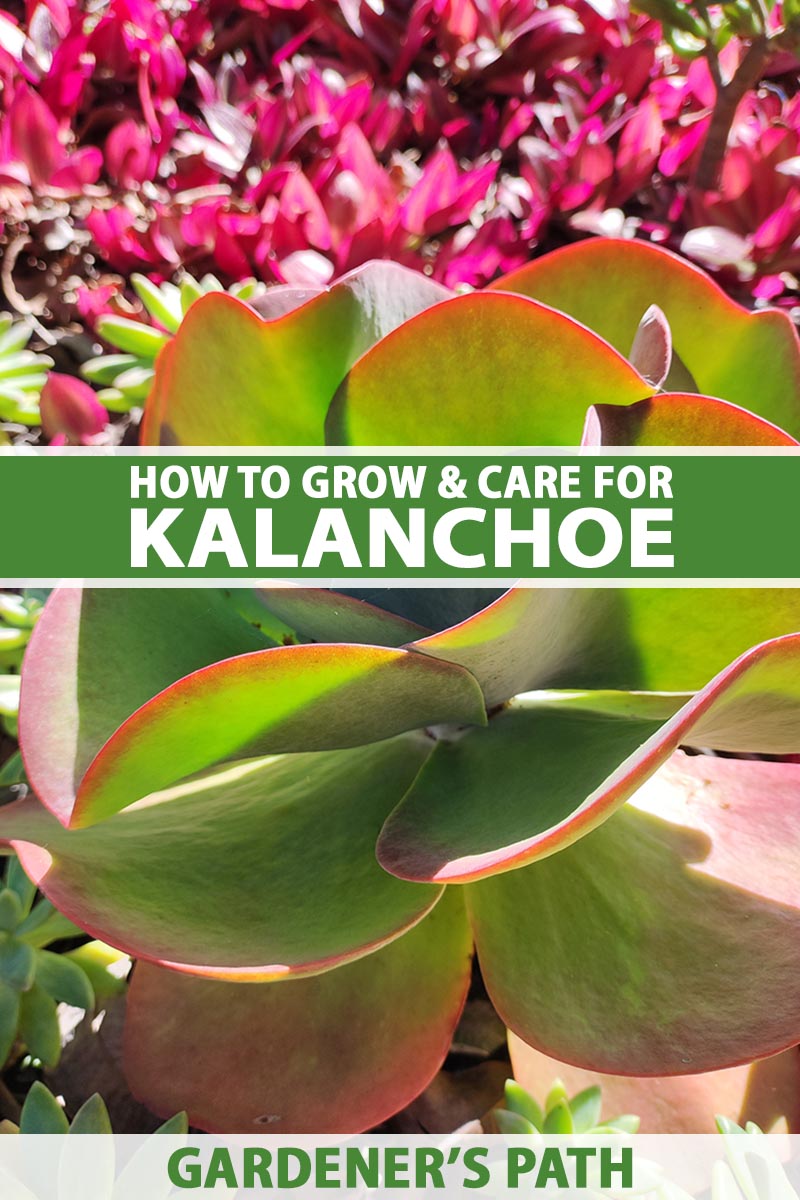

But these species don’t necessarily share visual similarities. In some cases, they don’t look at all alike.

Flapjacks (K. luciae), for example, has flat, circular leaves produced in stacks, while panda plant (K. tomentosa) has silvery fuzz on its blade-shaped leaves, and these may sport brown markings that look like streaks of chocolate.

Other types will start out with green leaves and develop red tints or maroon edges if they receive enough light.

The size range among plants in this genus is also impressive.

It includes specimens like the velvet leaf plant (K. beharensis) that can grow up to 20 feet tall outdoors under ideal conditions, along with dwarf floral varieties that bloom in bright colors and can live their whole lives in four-inch pots.

Most species are perennial herbaceous plants, but a few are annuals or biennials.

All are easy to propagate from cuttings.

And my personal favorites are the varieties that reproduce viviparously. Their leaves produce plantlets along their margins, complete with roots, and they fall off to grow into new plants.

You may be most familiar with the florist’s kalanchoe that’s often sold as a blooming houseplant in the months leading up to Christmas, and throughout the season of dull wintry weather to follow.

Single blooms of this species may be orange, pink, white, or yellow, and a double variety, ‘Calandiva’ or the rosebud kalanchoe, first came onto the market in 2002.

Another claim to fame: A kalanchoe was sent into orbit in a resupply mission to the Soviet Salyut 1 space station in 1979.

Would you like to try growing one a little closer to home? Read on! It’s going to be simple, and fun.

Propagation

If you’ve acquired a plant from a nursery or have a friend who’s growing kalanchoe and willing to share, it’s easy-peasy to grow more.

If you’re totally gung-ho on the idea, you could also grow kalanchoe from seed, but you can more reliably and far more readily root cuttings to produce new plants.

When you take cuttings, you’ll also always know what you’re growing – while cuttings produce clones, seeds may not produce kalanchoe with characteristics identical to the parent plants.

From Cuttings

To root branching kalanchoe types in potting mix, take stem-tip cuttings about three inches long, and remove any flowers.

Prepare a pot or tray of moistened cacti or succulent mix, or combine your own mixture with equal parts peat and vermiculite.

Poke the cut side of the stem into the soil about an inch deep.

Place the tray where it will receive bright, indirect light, and keep the soil moist but not wet until roots form. This usually takes a couple of weeks.

You can also propagate kalanchoe from leaf cuttings, but reserve this for the varieties that don’t have sturdy stems to cut. Choose those with thick, fleshy leaves that don’t produce new plantlets on their leaf margins.

Just a few of the many varieties that are suitable to start from leaf cuttings include panda plant, paddle plant, flapjack kalanchoe, and K. humilis.

Learn more about rooting leaf cuttings in our guide to propagating succulents.

From Plantlets

If you’re growing a viviparous species, meaning it produces new plantlets with their own roots along its leaf edges, it could not be simpler to propagate.

When the plantlets are able to live on their own, they’ll drop from the parent plant and stretch their roots into the soil at the base.

If you like, you can watch for the plantlets with roots, and gently dislodge them before they drop on their own. Then place them on the surface of lightly moistened cactus potting mix in a pot, or on the garden soil, and watch them do their thing.

In the garden, you may wish to protect your plantings with a chicken wire cage until they get established and begin to put on new growth.

To transplant out of starter pots, wait until the new starts produce a couple sets of new leaves. You can disentangle each transplant or plant a clump of three or four together.

Move them to their permanent home, either planting them in a suitable spot in the garden that’s been cultivated at least four inches deep, or placing them in a pot of pre-moistened succulent growing mix. Position them so the roots are lightly buried just below the surface of the soil.

From Seed

You can sow seeds if you are able to find them. For this, you’ll probably need a mature outdoor plant that has flowered and been pollinated to produce viable seeds. You may be able to locate seeds available for purchase as well.

The seeds are very tiny, like dust or grains of pollen. Try to plant more than you think you’ll need. Sow them indoors at any time, or outdoors when the temperature is reliably at or above 60°F at night.

Fill a shallow tray that provides drainage with seed-starting mix or soil formulated for succulents and spread the seeds on top of the soil, pressing lightly to just barely cover them.

Moisten the medium with water from a spray bottle and cover the top of the tray with clear plastic wrap or a dome to retain humidity.

Put the sealed tray in a protected area outdoors or indoors where it will receive bright, indirect light for at least four hours per day.

The plastic wrap or dome should keep the soil moist enough, but if you notice it has dried out, remove the plastic to mist the soil with more water and then replace the covering.

You can expect some of the seeds to germinate in a couple of weeks, though germination rates tend to be low.

How to Grow

Whether you’re growing kalanchoe outdoors year-round in a warm region, indoors as houseplants, or combining the two approaches by bringing potted plants inside to ensure protection through cold winters, bright light and good drainage are key.

For containers, be sure to choose a pot with good drainage that is large enough to hold the root structure with a little growing room to spare. Fill it with porous soil formulated for cacti and succulents.

Kalanchoe plants of all types do need some water, but they don’t like wet feet. Overly moist soil or sitting in water can lead to root rot, the most common reason for these easy-care plants to languish.

Outdoor kalanchoe specimens should be planted in-ground or their containers should be placed in a location that receives full sun to part shade, while houseplants will need bright, indirect light.

Supplemental lighting can also be used indoors if you don’t have a sunny windowsill available.

Plants that don’t receive much light will also get leggy quickly, and they won’t look as healthy or bloom as readily as plants with more light exposure.

Indoors or out, these plants also need nighttime temperatures of at least 60°F. Daytime temperatures around 70°F are ideal, though they can tolerate temperatures much warmer.

If you’re growing container kalanchoe in regions north of Zone 9 or 10 where they aren’t hardy, beware of the onset of cooler weather.

Make sure to bring potted plants into the house or place them in a heated greenhouse before temperatures dip below 40°F. These are tough plants, but they can’t withstand freezing temperatures.

Growing Tips

- Outdoors, place kalanchoe in full sun or moderate shade.

- Indoors, assure the succulents receive ample bright, indirect light.

- Pot in a well-draining mix specially formulated for succulents and cacti.

- Only water when the soil is dry to a depth of three to four inches.

Pruning and Maintenance

I promised you an easy-care plant, and the minimal maintenance required delivers on that promise.

Mostly, you’ll just need to water the plants any time the soil has dried out completely to a depth of several inches. It’s a good idea to use a moisture meter so you’ll know when to water, and this can help to prevent overwatering and root rot.

You can also remove any dead leaves or spent flowers every couple of months. This is more a matter of aesthetics, but unwanted pests and pathogens may find safe harbor here as well.

If you’re growing in containers, you may want to repot every year or two, depending on how fast your chosen variety grows. Look for roots peeking out the bottom through the drainage holes, and make sure to only move to a pot that’s one size larger.

Honestly, though, you can put that task off for years if you want to. These succulents don’t mind being a little root bound, and if they get a bit cramped, they just won’t grow as big or as quickly.

The next biggest portion of kalanchoe maintenance is making sure to move your plants indoors in the winter well ahead of frost if you live in a region with cold winters, or if a rare cold snap is in the forecast.

They’ll tolerate drought, but frost and freezes will kill them.

If you can’t move the plants because they’re growing in the ground, row cover or plastic might help prevent an unexpected freeze from claiming the plants.

I always recommend taking a few cuttings to root ahead of any freezes in the forecast if you’re growing succulents as perennials. That way you can root the cuttings if anything happens to the garden plants.

If you end up with extra cuttings you don’t need, another succulent lover will probably appreciate the starts, or you can always compost them.

One other maintenance task is optional:

You can prune these plants to shape them if you like. Only cut a few inches from the top of any stems that have grown lanky, and keep in mind that this is typically a sign of inadequate light exposure.

Mostly, though, you’ll only need to cut these freewheeling plants in order to root the leaves or stems if you wish to propagate more. That’s a prospect to look forward to!

Species to Select

With over 100 species in the Kalanchoe genus, most of these are not in cultivation. But the ones that are readily available to the home gardener are still quite diverse.

Here are a few of the most popular varieties you might want to opt for to grow at home:

Florist’s Kalanchoe

K. blossfeldiana, or florist’s kalanchoe, aka flaming katy, is known for being one of the easiest varieties to grow among flowering houseplants.

With a max height of about 12 to 18 inches – several more including the blooms – and a spread of about a foot, it produces clusters of flowers that may be white, yellow, orange, or pink, depending on the variety.

The foliage is fleshy and green, with scalloped edges.

It’s simple to grow indoors, especially if you also bring it outdoors during the warmer months in your area to provide it with lots of light.

Those in Zones 9 to 11 can grow flaming Katy outdoors as a perennial, and it should rebloom without any extra steps required.

This type usually appears at retailers in late fall and early winter in cooler regions, just in time for some cold-weather indoor color. You may find these plants marketed as Christmas kalanchoe for this very reason.

Bear in mind that while you can force plants grown indoors to bloom again, the process takes about 12 weeks, beginning the previous fall. You can learn more about encouraging kalanchoe to rebloom indoors in our guide.

Yellow-flowering K. blossfeldiana plants in two-and-a-half-inch containers are available from Hirt’s Gardens via Walmart.

Or read more about caring for florist’s kalanchoe/flaming katy here.

Mother of Thousands

K. daigremontiana reproduces readily from both cuttings and the little plantlets that develop along the edges of its leaves.

It features bright green foliage with saw-toothed edges on fleshy stems.

It’s similar to the mother of millions kalanchoe but has larger leaves that grow up to eight inches long, compared to the other plant’s more pointed, darker leaves that grow to about four inches max.

Mother of millions also produces plantlets on the top of its leaves, while mother of thousands may grow them all along the leaf margins.

Mother of thousands is hardy in Zones 9 to 11. Outdoors it flowers in winter and then dies, producing bell-shaped red-orange blossoms that hang down in a ring from a tall stem.

Planted in the ground, it can reach three feet tall. If its pot is large enough and it receives ample light, it can also grow to this size in a container.

Begin with a more modestly sized four-inch pot of ‘Mother of Thousands,’ available from Hirt’s Gardens via Walmart.

Panda Plant

With the botanical name K. tomentosa, panda plant is also called pussy ears and chocolate soldier – not to be confused with the columbine cultivar of the same name, or with the flame violet (Episcia cupreata) which also sometimes goes by this common name.

Noted as a foliage plant, it is valued for its fuzzy leaves – silvery with chocolate-brown piping along the margins – more than its blooms. But it may sport clusters of purple-tipped, yellow-green flowers in spring.

These sizable succulents are a suitable accent for gardens and borders in Zones 11 to 12, and they also offer indoor appeal as houseplants.

They can grow three feet tall and two or three feet wide under ideal conditions, so be sure to reserve these for a larger container, not a dish garden.

Learn more about growing and caring for panda plant in our guide.

Two-and-a-half-inch pots of K. tomentosa are available from Hirt’s Gardens via Walmart.

Managing Pests and Disease

Like most of their succulent kin, kalanchoe is known for being relatively pest- and disease-free. These are the main issues to watch for:

Insect Pests and Arachnids

You can help these succulents avoid common pests by inspecting them often. Most pests that afflict kalanchoe can be taken care of easily in the early stages but are more difficult to deal with once they gain a stronghold.

Mealybugs

Mealybugs are insects in the Pseudococcidae family. The nymphs and adult females are less than a centimeter long – tiny!

The adult males look like gnats and are even tinier. Since they don’t live for more than a few days while mating and they won’t feed on your plants, they’re not a big concern.

But the females and nymphs can do plenty of damage, feeding on all parts of the plant and sometimes nestling right beneath the soil.

They secrete a sticky “honeydew” that promotes the growth of unattractive, stubborn black sooty mold.

The females also lay hundreds of eggs in crevices of the plants they infest, and they’re covered by a waxy substance that makes them hard to remove.

Long-tailed mealybugs don’t lay eggs, instead bearing live young that immediately start crawling around.

They can still cover plants with honeydew excretions and unsightly cocoons, and they also inject saliva into the leaves as they dine, potentially spreading disease.

To prevent mealybug infestations, inspect your plants often, particularly in the nooks and crannies between stems and leaves, which are their favorite hiding places.

It’s essential to detect and eliminate any bugs that have attacked potted outdoor kalanchoes before you bring them indoors to overwinter.

Be extra vigilant in the weeks ahead of the move, since any mealybugs that make it inside can spread to other houseplants, too.

If you spot just a few, you can usually wipe them off with a cotton swab dipped in rubbing alcohol.

To learn more ways to detect and eliminate mealybugs, read our guide.

Scale

Also icky and sticky and related to mealybugs, scale insects suck sap from fleshy plant parts.

They’re tiny, waxy, and usually white, brown, or gray.

If you spot an infestation early enough, and if you see just a few, you can use a rubbing-alcohol-dampened cotton ball or swab to wipe them off the plants manually.

More severe infestations may require insecticidal soap or neem oil to eradicate.

And if scale insects are gaining the upper hand with your plants outdoors, you may want to consider introducing beneficial insects to the area that love to feast on these pests.

Learn more about preventing and eradicating scale in our guide.

Spider Mites

If you have arachnophobia, you may not want to inspect these teeny-tiny pests up close.

You’ll usually only see the webbing they leave behind, but if you spot the mites themselves, you can see they’re tiny arachnids.

These sap-suckers from the Teranychidae family can attack kalanchoe and leave behind discolored streaks, yellowed leaves, or brown spots on the leaves that get darker and larger with time.

Prevention and early detection are key. You can discourage them in the early stages by dusting your houseplants regularly or occasionally setting outdoor pots where they’ll catch a morning rain shower or spray from the hose.

Just leave enough time for the leaves to dry before dark, so the evening humidity won’t encourage fungal infections.

Also, make it a point to inspect the plants before bringing them indoors if they spend several months outside.

If you see mites or webbing, get rid of them beginning a few weeks before bringing plants indoors to overwinter. Spray them off with a hose outdoors in warm weather, in the morning so the leaves have plenty of time to dry.

Follow up with another blast once a week until you no longer see them or their webs.

If mites appear indoors, quickly isolate the infested kalanchoe so they don’t spread to your other houseplants. These pests are not uncommon indoors, especially in dry conditions.

Then wipe off the spider mites – and their webbing – with a damp cloth. That should take care of the issue as long as the infestation is minimal.

If the problem is more widespread, you may need to apply neem oil following the manufacturer’s instructions, or spray the affected leaves with a few drops of rosemary essential oil added to a spray bottle of water.

For more tips on coping with spider mites, see our guide.

Diseases

Kalanchoe isn’t prone to many diseases, which is one of the reasons why it’s described as “easy care.” But keep an eye out for these potential ailments:

Powdery Mildew

If you see floury spores on the leaves, you may be dealing with powdery mildew. It’s caused by fungal parasites in the Erysiphe genus, which feed on and weaken plants.

The spores reproduce in humid environments, even in the absence of moist soil or standing water.

If you notice it in time, you can probably eliminate powdery mildew by wiping it from affected areas with a water-dampened cloth.

More advanced cases might require treatment with fungicides. Learn more about home remedies for powdery mildew in our guide.

Root Rot

Root rot is devastating for us succulent lovers since the only solution is to toss affected plants and the soil they’re growing in.

Rhizoctonia solani or Fusarium fungi typically cause the root rot, which announces itself with mushy, black or brown root systems – and usually, a telltale rotting smell.

Be sure to protect your kalanchoe from root rot by only watering at the soil line, never overwatering, and never letting the plants rest in pooled water.

Only choose pots and soil that drain readily, and be sure to pour the excess out of any saucers placed beneath pots.

Best Uses

The Kalanchoe genus includes a wide variety of plants that are sure to delight indoor and outdoor gardeners in numerous ways.

If you live in Zones 10 to 12 where most varieties can be grown outdoors as perennials, you may want to plant kalanchoe as an accent in a bed or border, add it to a rock garden, or use it for xeriscaping in arid climates.

You can also make use of their tolerance for dry spells and drought to grow them as ground cover. In general, you’ll want to plant the lower-lying, spreading types to grow over a bare or sloped spot in the landscape.

The larger varieties will also work to cover ground, as long as you’re okay with their tendency to grow three feet tall and form a sort of thicket.

And keep in mind that mother of millions and mother of thousands are both considered invasive in some areas.

They’re tough to control once they start dropping those plantlets everywhere, so only grow them in beds or as ground cover if you are certain you can contain them.

Houseplant aficionados can employ many varieties as centerpieces or dish garden specimens, and flaming Katy in particular will bloom readily indoors.

And as a bonus, unlike the monocarpic succulents that only bloom once before they die, many varieties of kalanchoe can bloom numerous times, with some coddling as needed.

If you are going to try to get repeat blooms indoors, you won’t want to plant them in a container with other small succulents, since part of the process involves low light conditions that can tax other plants.

Probably my favorite option is to share or swap kalanchoe with other gardeners. It’s so simple even for beginners to grow them from cuttings or plantlets that they’re a natural for giveaways, school projects, or door prizes.

Both floral and foliage varieties also make excellent inexpensive party favors you can grow yourself.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Succulent | Flower / Foliage Color: | Orange, pink, red, yellow, white/brown, burgundy, copper, green, purple, silver (sometimes red with light exposure) |

| Native to: | Africa | Maintenance | Low |

| Hardiness (USDA Zone): | 9-12, depending on variety | Tolerance: | Drought, poor soil, light shade |

| Bloom Time: | Winter, spring, or summer, depending on type | Soil Type: | Sandy loam; succulent growing mix |

| Exposure: | Full sun to moderate shade (outdoors); bright, indirect light (indoors) | Soil pH: | 6.5-7.5 |

| Spacing | 6-36 inches | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Planting Depth: | Surface of soil (transplants or plantlets); barely cover (seeds) | Uses: | Beds, borders, containers, houseplants, rock gardens, xeriscaping |

| Height: | 3 inches-20 feet, depending on variety | Order: | Saxifragales |

| Spread: | Up to 36 inches, depending on variety | Family: | Crassulaceae |

| Water Needs: | Low | Genus: | Kalanchoe |

| Common Pests and Diseases: | Mealybugs, scale, spider mites; leaf spot, powdery mildew, root rot | Species: | Beharensis, blossfeldiana, daigremontiana, delagoensis,, humilis, longiflora, luciae, marnieriana, pumila, thyrsiflora, tomentosa |

Kalanchoe Rhymes with Showy – or Zowie!

No matter how you decide to pronounce the name, I hope you’ll think about adding one or two kalanchoes to your collection of garden favorites or houseplants.

Be forewarned, though: They’re so easy to propagate, you may very easily end up with more plants than you know what to do with!

Of course, it’s also simple to share the extras with beginners and fellow succulent fans. The process demands only a minimal investment, with little required beyond a few extra containers and some potting soil.

Regarding sharing, if you have kalanchoe varieties you favor or questions we didn’t get to here, kindly pass along your input in the comments section below.

And if you’re looking for information on other easy-care succulents to grow at home, check out these guides next: