A greenhouse serves as a fantastic option to grow plants in locations or seasons where they wouldn’t fare well by themselves due to the local weather conditions and climate.

Plus, they can be a stylish addition to the landscape in their own right! I mean, what building adds to the gardener aesthetic better than a hothouse?

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

But a hothouse is more than just a structure. It also creates a miniature ecosystem, one that you’ll have to maintain at a certain temperature in order to keep the plants within alive. Sometimes this means lowering the temperature, other times raising it.

It’s the latter that we’ll be discussing in this guide. In addition to types of greenhouse heating, we’ll cover the basics of glasshouse heat, along with things you’ll want to consider when selecting a method to use in your own backyard.

For some expertise on this topic, I recruited the aid of a former teacher: Dr. Mary Ann Gowdy, Teaching Assistant Professor of Plant Science and Technology at the University of Missouri-Columbia.

Holding a PhD in crop science with an emphasis in greenhouse production, she certainly knows her stuff! Plus, Dr. Gowdy’s not grading me on this, which certainly takes the pressure off.

Here’s everything that awaits in this guide:

What You’ll Learn

Greenhouse Heating 101

Keeping a hothouse at a desired temperature comes down to simple thermodynamics: heat loss must equal heat gain.

If that equation becomes unbalanced towards either side, then the plants within the glasshouse will either freeze or fry. And there are multiple ways that a greenhouse can lose warmth.

Conduction occurs when heat is lost as it transfers into and out of the materials that make up the glasshouse, such as the doors, fans, metal purlins, and glazing.

Kind of like when you bite into a hot potato, and some of that warmth painfully travels into your tongue, esophagus, and the roof of your mouth. The majority of a hothouse’s heat loss is due to conduction.

Infiltration and exfiltration are other forms of loss. This is when heat physically escapes through empty spaces, such as vents, the gaps between building materials, or your open mouth after that aforementioned hot potato bite.

Even in a tightly secured hothouse, up to 10 percent of its heat loss may be due to infiltration and exfiltration.

The final form of loss is radiation. Other than glasshouse glazing made of polyethylene film, most greenhouse materials don’t allow radiant energy to pass through.

Much of the time, this loss of warmth is something you will try as a gardener to prevent, by either adding more heat or taking measures to prevent losses in the first place.

But sometimes, you want to deliberately cool a hothouse in order to keep it from becoming too warm. Fans, ventilation, and evaporative cooling are all effective ways to quickly lower a glasshouse’s temperature – we cover these in another guide.

Now that you know how greenhouse heat may be lost, let’s turn our attention to intentional gains, and maintenance of a particular target temperature.

Ways to Heat a Greenhouse

I’ll fess up: covering every single type of greenhouse heating is beyond the scope of this guide. Utilizing compost to heat a greenhouse, for example, is a subject that needs its own article.

For the average hobby gardener, the following ways of warming a glasshouse should serve your purposes nicely, or at least provide a solid starting point.

The Sun

When considering heating options, it’s impossible to ignore the giant, hot, and free-to-use ball of energy in the sky. The sun makes it possible to keep even the most basic greenhouse warm.

As sunlight hits the glazing material of a hothouse – usually glass, polycarbonate, or a polyethylene film – the glaze diffuses the light throughout the entire structure. As the light hits plants and materials inside, the light energy is converted to heat energy.

This heat can’t leave the greenhouse as easily as light is able to enter it, so it remains trapped in the hothouse, increasing the temperature.

There’s not much you can do to alter the sun’s location or intensity, but we gardeners have many different ways of making the most out of its rays.

Prior to construction, we can use sun charts to check the sun’s position in our location at certain times, which helps us orient our greenhouses in a position that best utilizes the available sunlight.

We can also select certain glazing materials. Each material comes with advantages and disadvantages in terms of its ability to transmit light, thermal conductivity, weight, durability, cost, and longevity. All of these factors should be considered when making construction decisions.

We can also place thermal mass materials and objects throughout our glasshouse for the sole purpose of capturing light and releasing it as heat. Dense materials like brick, tile, and concrete have a higher thermal mass than, say, wood and cloth do, which makes them ideal for use as thermal mass objects.

Even color can have an impact – dark thermal mass objects such as darkly-painted water jugs do a better job of converting light to heat than lighter-colored objects do, which may serve to reflect light instead.

But solely relying on the sun has its drawbacks.

“The heat loss of greenhouses is significant, even if you’re trying to minimize loss,” Gowdy says. “So, the problem is you get a lot of heat during the day when you don’t need it, then when the sun goes down, you lose what was in there.”

Gowdy recommends utilizing more than just the sun if the temperatures in your area plummet to a range of 30 to 40°F.

Plus, as awesomely powerful as the sun is, it does have that annoying tendency to disappear at night.

Unless you have enough thermal mass stored up in your glasshouse to keep it warm during dark hours, you may have to increase the temperature in other ways if season extension is what you’re after.

Hot Water Heating Systems

Using hot water heating systems requires a lot of forethought and planning, but they’re quite effective when executed properly.

In essence, these systems warm up water with a boiler, then pump it throughout the hothouse via a network of pipes.

Heat is released from the pipes as the hot water travels through them, which then warms adjacent spaces and materials. A central controller is used to make adjustments as needed.

The hot water system doesn’t even have to utilize liquid water – it can also be used in vapor form.

In these systems, steam is produced by the boiler instead of hot water, which then travels through the pipes via pressure instead of pumps. Gasses have more energy than liquids, so steam will warm your glasshouse more efficiently than liquid water would.

Another cool thing about hot water systems is that you can control exactly where you want the heat to go. You can run the pipes under or on top of the floor, directly under growing benches, along the walls, or above the plants via ceiling attachments.

With proper piping placement, plants can be kept sufficiently warm without losing excess heat to empty space, making hot water one of the most energy-efficient systems out there.

There are many potential fuel sources that a hot water system could use – natural gas, propane, wood, coal, solar energy, and other forms of electricity are just some of the options available, and each comes with its own pros and cons.

Unit Heaters

According to Gowdy, unit heaters are the simplest heat source that a home gardener can put in a greenhouse.

It’s a great alternative for hothouse owners looking for something a bit less convoluted than a hot water system. Typically fueled with natural gas, propane, or oil, unit heaters are compact, inexpensive, and quite reliable.

Basically, unit heaters combust fuel, which results in hot exhaust passing through metal structures called heat exchangers.

A fan that’s behind the unit draws in air from the greenhouse, forcing it over the heat exchanger. The warmth from the heat exchanger passes into the air, and circulates throughout the space.

But blowing hot air on its own usually isn’t enough, according to Gowdy. You’ll also need a fan to circulate the air. “You’ll probably need more than one fan if your [green]house is more than 20 feet long,” she says.

For a high-performance, low-noise horizontal airflow fan with a high-quality motor, efficient fan blades, and durable steel guards that are also corrosion-resistant, have a look at the Schaefer Versa-Kool Circulation fan, available from Amazon.

Schaefer Versa-Kool Circulation Fan

Since these heaters require so much oxygen to operate, an air line running to the outside of the glasshouse can also be hooked up to the heater, which keeps the oxygen within the greenhouse from being used up at a stupidly high rate.

With unit heaters, you have the freedom to install them throughout the hothouse as you please, typically hanging from the ceiling, whereas hot water systems are a bit tougher to restructure on a whim.

However, hot air heat is not as energy-efficient as hot water, and this is worth considering.

Bio Green Phoenix 2.8Kw Heater

Bio Green sells a stainless steel, 2.8Kw corded glasshouse heater with hanging chains included on Amazon and Gardener’s Supply Company.

Bio Green also offers a more compact, 1.5Kw splash-proof model suitable for smaller spaces.

Radiant Heaters

Radiant heaters work by warming up an aluminum tube until it reaches approximately 900°F, at which point it starts to emit infrared radiation.

Directed outward by means of a nearby reflector, the radiation strikes plants and surfaces, which absorb it and convert it to heat. This warmth then emanates throughout the greenhouse.

Surfaces warmed by radiant heaters are typically warmer than the adjacent air, which makes for very cost-efficient heating.

The initial installation costs can be pricey, and avoiding cold spots via proper placement is essential. However, if neither of those are intimidating factors, then radiant heaters may be a worthwhile option for you.

Radiant Heating Propane Gas System

To purchase a propane-fueled radiant heater with a built-in thermostat, visit The Home Depot.

Thermal Blankets

For a plant parent who takes the title pretty seriously, using a thermal blanket to keep plants warm overnight can feel a lot like tucking them in.

“It’s the same idea as when you go to bed at night and pull a blanket over yourself,” Gowdy says. “The blanket’s not warming you[…] the blanket’s trapping the heat that your body’s radiating, so it gets nice and toasty.”

When you cover growing specimens with a thermal blanket, these cloth or plastic coverings allow for a more efficient use of warmth, because the heat won’t rise towards the ceiling of the greenhouse where there aren’t any plants to utilize it.

Agribon Floating Row Crop Cover

For an ultralight, long-lasting polypropylene cover that’s sold in a variety of dimensions, head over to Amazon.

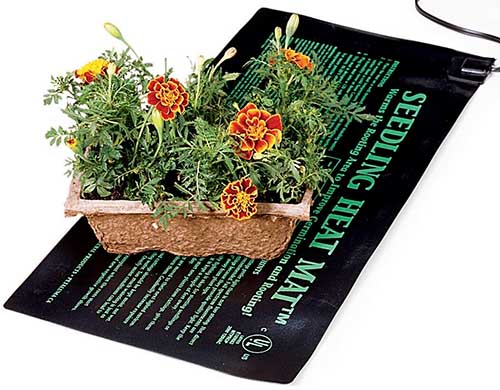

Electric Heating Mats

What do you do if certain plants – such as seedlings – need warmer conditions than others, but raising the entire glasshouse’s temperature is inefficient, or won’t serve to meet your needs overall?

Electric heating mats provide a nice way to directly conduct heat to the base of certain pots and containers while leaving others alone.

For a heating mat with a six-foot-long power cord that adds 10 to 20 degrees to the nearby ambient temperature, visit Gardener’s Supply.

Factors to Consider

So, you have some options now. But how do you choose? Personal preference should definitely be taken into account, but the following elements will help you to make a truly objective decision.

Operation Costs

Most hobby gardeners are limited by their disposable income… I know I am. When choosing a system or equipment to keep your greenhouse nice and toasty, you first have to decide how much money you’re willing and able to spend.

Once you have that amount in mind, it’s time to crunch the numbers.

Whether it’s on a spreadsheet, in your gardening journal, or with one of those old-school printing calculators, simply add up what you’re thinking of buying until you reach your allotted amount of moolah.

If you’re over budget, you’ll have to choose less costly means of heating.

Modifying an already-existing greenhouse may be less expensive than building a new one from scratch, depending on what heating method you use.

Per unit of heat produced, here are some standard greenhouse heating fuel sources in order from cheapest to most expensive, for your consideration: natural gas, wood, propane, heating oil, and electricity.

Local availability of resources and utility costs as well as installation costs for items you’re not able to set up yourself should also be considered.

Greenhouse Size

Larger greenhouses both require and lose greater amounts of heat than smaller ones.

While a hobbyist with a shed-sized backyard hothouse could probably make do with the sun and a single heater, a glasshouse sized for commercial production will almost certainly require something bigger, higher-powered, and more involved to maintain the same level of warmth.

Calculating the interior volume of an existing greenhouse largely depends on the structure of the roof. A basic equation is to multiply the width, length, and height together – this would give the volume for a rectangle-shaped structure. You’ll then need to factor in the volume of the roof section.

You can find a handy calculator here.

Make sure to double-check the size specifications of your heating systems, as well as how much space they need for operation.

Heat Requirements

This is primarily dependent on where you’ve placed your greenhouse, what growing zone you’re in, and what you plan to grow inside it. A greenhouse in Florida is going to need less heating than one in Minnesota for example.

In the greenhouse industry, heating is measured in British thermal units (Btu), with a single Btu being the amount of heat required to increase the temperature of a pound of water by one degree Fahrenheit.

Many systems and products describe their output in Btus, and this unit of measurement can be helpful in calculating which forms of heating will meet your needs based on the square footage and volume of your setup.

Maintenance Requirements

It’s pretty simple to leave a pile of bricks in your glasshouse for use as thermal mass objects. Fixing a broken boiler or installing a network of pipes… that’s a bit tougher.

Not to mention more expensive, if you don’t have the expertise to get set up or make the necessary repairs yourself.

Luckily, you can always hire out for installation and repair services – but that’s yet another cost to consider.

Those do-it-yourself types who pride themselves on self-sufficiency – especially those living in deeply rural areas – might benefit from choosing a heating type that they can install and maintain themselves.

Either way, be sure to check any warranty information and guarantees before you purchase.

If these components break down on you, the last thing you’ll need is any financial woes.

Sustainability

Maybe the idea of all that manufactured material and burning fuel causes strife in your eco-conscience.

Environmentally-conscious folks might opt for efficient systems fueled by clean sources of energy over a more conventional or perhaps convenient form of warming. If that’s you, then more power to ya.

“Electricity is clean, because you don’t have to worry about exhaust fumes… but it’s very expensive,” says Gowdy. This obviously depends on who’s powering your local municipal hookup, but solar panels make for an energy source that’s 100 percent emission-free.

Gowdy also mentioned wood as a solid choice in terms of “clean” fuel for a boiler, “as long as you have access to the wood, and you’re willing to get up in the middle of the night to make sure that it’s working and it’s got fuel.”

Ultimately you need to weigh up your options based on what is easily accessible to you and how much of an environmental impact it has.

Greenhouse Heat: It’s Pretty Neat

Hopefully, you now have a decent understanding of how greenhouses keep warm, along with some ideas for warming up your own hothouse.

Personally, I think a hothouse is something that’s more difficult to wrap one’s head around conceptually than it is in practice, so don’t stress out if some of the details we’ve covered in this basic primer sound super complicated!

Glasshouses become a whole lot simpler once you start working with one in real life, adjusting to your local climate and tending to the specific plants you’ve opted to place inside.

Another thanks to Dr. Gowdy, whose greenhouse know-how was super helpful in crafting this guide!

Questions or remarks can go in the comments section below. This is an area in which personal anecdotes can be super helpful, so don’t be shy about sharing photos and details about your hothouse setup!

For more greenhouse growing guides, check out what we’ve got on tap:

Glad I read this, it gave me an idea! We have an old gravity-fed oil drip stove that we’re planning on putting in our house when we build one. Until then, it’s just taking up space… So, I just thought, let’s set it up in the greenhouse! We collect waste veggie oil from restaurants, so we have the fuel, but we’re also completely off-grid and require options that don’t rely on electricity 😉