Spodoptera exigua

Despite its common name – beet armyworm – pointing to one specific crop, no garden is safe from this pest. It will chow down on everything from corn to tomatoes to flowers.

If only our kids loved as many different types of vegetables as the immature larvae of this hungry moth!

Able to skeletonize leaves, burrow into plant crowns, and kill seedlings and young plants, Spodoptera exigua is a daunting foe.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

Luckily, there are some steps you can take if they invade your lush garden plot. Everything you need to know about these chewing pests is laid out for you below.

Here’s what we’ll cover:

What You’ll Learn

What Are Beet Armyworms?

Beet armyworms originated in southeast Asia and were first discovered in North America in Oregon in 1876.

They are in the Noctuidae family, along with other types of cutworms and armyworms.

They rarely overwinter in regions where frost kills their host plants, so they must reinvade these areas annually. Thus, beet armyworms are often more significant pests in southern states and in greenhouses.

Their host range is wide, including a variety of vegetable, field, and flower crops.

Asparagus, beets, cabbage, chrysanthemums, corn, onions, peas, peppers, tomatoes, and turnips are just a few of their favorites. They like weeds too, such as lamb’s-quarter, mullein, pigweed, and purslane.

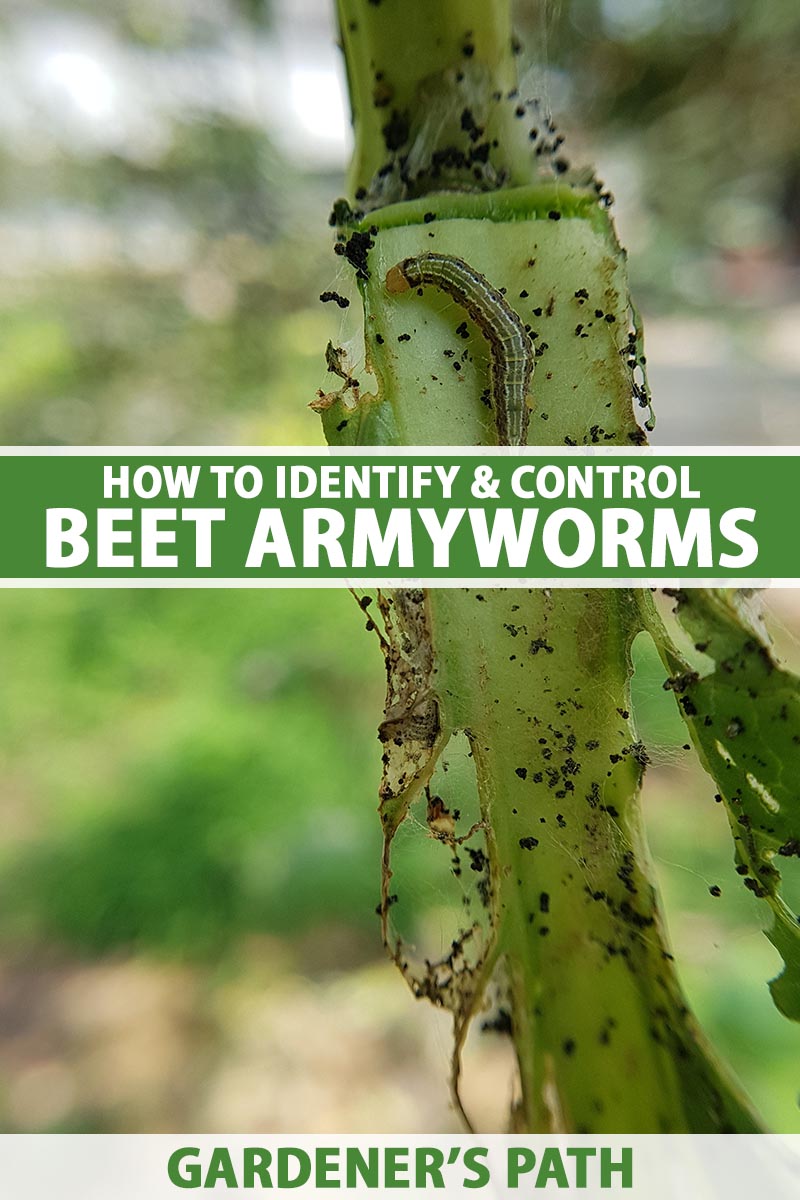

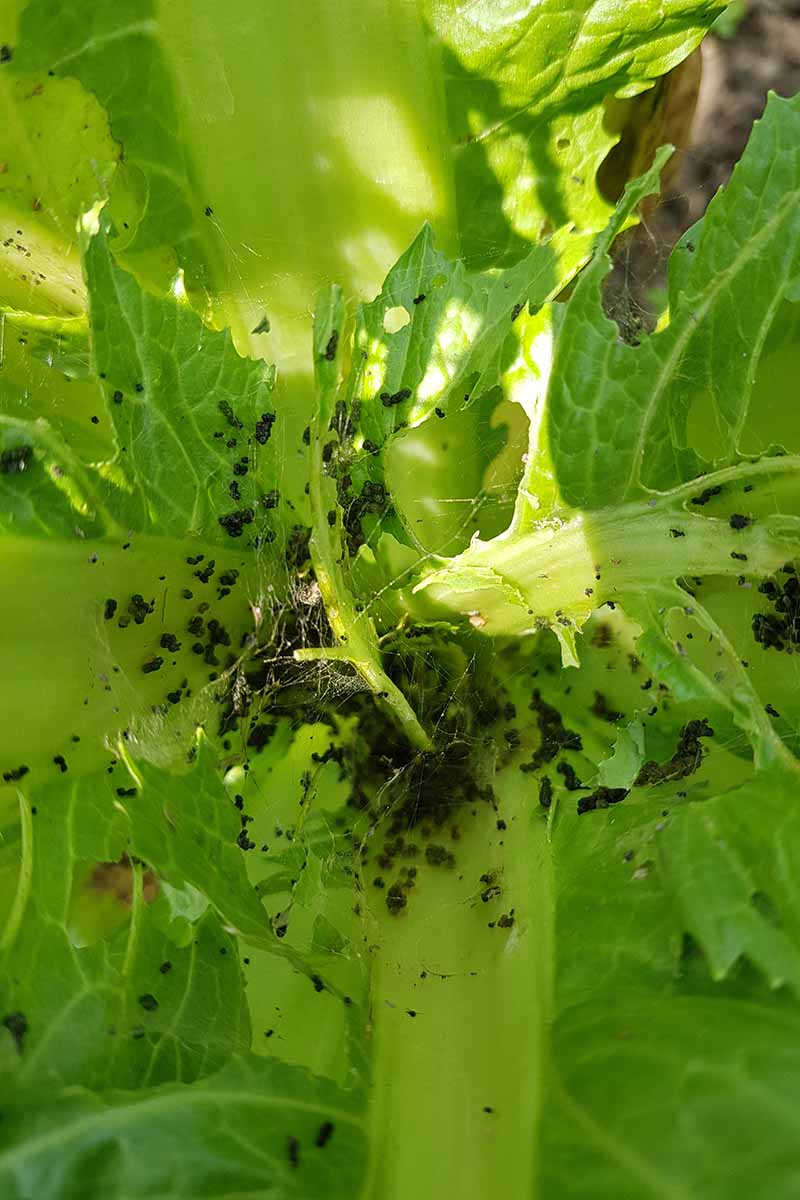

Both the adults and larvae feed on the plants, but the larvae are the main concern. Young larvae feed in groups and can skeletonize leaves. They often create light webbing between the foliage, sticking leaves together as well.

More mature larvae prefer the growing tips of foliage and feed solo, but they can also cause significant damage.

They chew large, irregularly shaped holes in the leaves, plus they will burrow into the crowns and buds of plants. Larval feeding can stunt or kill seedlings and young plants.

Beet Armyworm Identification

The adults are moths with a one-inch wingspan.

Their forewings are mottled gray and brown, with an irregular banded pattern and a characteristic light-colored, bean-shaped spot.

The hindwings, which are only visible when they’re flying and tucked out of sight when at rest, are light gray or white with dark margins.

Beet armyworm eggs are greenish white and look circular when viewed from the top, but if you look at them from the side, you’ll see that they taper to a slight point on the ends.

The adult females cover the eggs with a layer of hairs or scales, which gives the mass a fuzzy appearance and protects it from potential threats.

The coloring of the smooth-skinned larvae varies depending on their stage of development, and they can reach one and a quarter inches long.

During the first and second instars, they are light green or yellow with pale stripes.

In the third and fourth instars, they darken dorsally and have a dark lateral stripe.

Fifth instar coloring and markings can vary, but they are often green dorsally, with a pink or yellow ventral stripe and a white lateral stripe. They might have some dark spots or dorsal dashes as well.

The pupae are light brown and about half an inch long.

Though these pests are easily confused with the southern armyworm (Spodoptera eridania), the larvae of this species has a distinctive large, dark spot positioned laterally on the first abdominal segment, which can help you to tell the difference between the two.

Biology and Life Cycle

This pest can complete several generations per year. In warm climates, such as in Florida, six generations can be completed in five months of summer weather.

One generation can take as little as 24 days to complete, though 30 to 40 days is more typical. Pests of all stages of the life cycle can be found throughout the year.

Each female produces 300 to 600 eggs, and lays them in clusters of 50 to 150 on leaf undersides, near flowers, and on branch tips.

The eggs hatch within two to three days during periods of warm weather and go through five, or sometimes more, instars. Each instar stage takes two to three days to complete.

They pupate about half an inch deep in the soil, in chambers made of soil particles glued together with a sticky secretion that hardens when it’s dry.

Adults may emerge in six to seven days, but pupating is often the overwintering stage.

The adults are nocturnal, doing most of their mating and egg laying at night. Mating begins soon after they emerge, and egg laying happens two to three days later, over the course of three to seven days.

The adults are short lived and die nine or 10 days after emerging.

Monitoring

Monitoring is a crucial step in the management process. Knowing when beet armyworms are invading and where the hotspots are can help you decide when and where to treat for them.

Monitoring can be done with pheromone traps. Note that these traps are not effective at controlling or reducing populations.

You can find lures specifically for beet armyworms at Arbico Organics, and these can be used with a delta trap or wing trap, both of which are also available from Arbico.

Check your plants for damage and the presence of any larvae two times per week during the growing season.

Don’t forget to check this pest’s favorite weeds too!

Adults will invade your vegetable plot from the surrounding areas, such as weedy ditches and other gardens and fields, so it is useful to know if they are hanging out nearby.

Organic Control Methods

For the safest, most effective means of control, it’s best to use a variety of control methods as part of an integrated pest management (IPM) strategy to reduce their numbers.

These methods range from handpicking the larvae to applying live natural enemies to hunt the pests for you.

Cultural and Physical Control

Since these insects love certain types of weeds, aim to destroy their favorite weeds if they are growing near your garden, to reduce spread from the margins to your plants.

Scout the veggie patch often throughout the season, and destroy affected foliage or handpick and destroy the eggs and larvae when you spot them.

After harvesting, cultivate the plot to expose and kill any prepupae and pupae that are in the soil.

You can use exclusion tactics and materials, such as floating row covers, to protect your plants from the moths that wish to lay eggs on your plants.

But note that this is only going to be effective if you haven’t had an infestation previously and know with certainty that there aren’t any pupae already in the soil, waiting to hatch under the rows.

Biological Control

Biological control options include attracting or purchasing and applying natural biological enemies to help keep pest populations down.

These can be effective enough to keep levels below the action thresholds for utilizing chemical treatments, but the mortality rate each natural enemy achieves will vary according to geographical region and the specific crops you are growing.

The eggs and small larvae of this pest are not safe out there. Minute pirate bugs, big-eyed bugs, damselflies, and predatory stink bugs are all on the prowl for these tasty morsels.

Plus, two species of parasitoid wasps, Chelonus insularis and Meteorus autographae, like to lay their eggs in the larvae. And Lespesia archippivora is a small tachinid fly which also targets the larvae that are munching their way through your precious vegetables.

There are also certain fungal pathogens, including species of Erynia and Metarhizium rileyi (syn. Nomurea rileyi), which will kill off some of the larvae before they become a problem for you.

Solenopsis invicta, the red imported fire ant, will also attack the pupae, but it happens to be a significant pest itself. Beneficial nematodes are a better option for pupae control.

Both Steinonerma and Heterorhabditis species of nematodes will infect beet armyworms in their prepupal and pupal stages in the soil.

NemAttack and NemaSeek Beneficial Nematodes

Both are available for purchase at Arbico Organics in a handy combo pack. Apply these according to the label instructions to achieve control of both the mobile prepupae and immobile pupae.

Organic Pesticides

It can be hard to achieve control of beet armyworms with insecticide applications, since the cottony scale-covered eggs and young larvae are hard to reach, and the older, bigger larvae are not as susceptible to pesticides.

Plus, these insects have developed resistance to many commonly used pesticides.

Whether you are using organic or chemical pesticides, application timing is key. Most products are only useful when they are applied before the larvae are half an inch long. Thorough coverage, whether of the leaves the larvae are eating or of the insects themselves, is also very important.

Neem oil can be used to combat the larvae. It is available from Bonide in gallon- and quart-size ready to use bottles, as well as in a pint-size concentrate, at Arbico Organics.

The larvae are susceptible to a variety of beneficial bacteria known as Bacillus thuringiensis v. aizawai, or Bta, which is available at Arbico Organics under the trade name Agree WG.

Bta works best on very young larvae, so this is where vigilant monitoring to find the larvae before they are too big will pay off!

Spinosad is also effective against a variety of pests, including armyworms.

Bonide Insecticidal Super Soap

Bonide Insecticidal Super Soap, which is available at Arbico Organics, combines the benefits and effects of Spinosad and insecticidal soap, and is safe for use on both edible and ornamental plants.

Chemical Pesticides

Pests that are resistant to pesticides present a major problem for gardeners and farmers alike, and the beet armyworm is no exception.

Chemicals are frequently and abundantly used on the foliage of susceptible crops to prevent and control beet armyworm infestations, and this promotes the development of resistance.

Use alternative control methods if possible, such as those described above.

Pyrethroids such as Sevin, available at Home Depot, can be an effective choice for dealing with invasions of beet armyworms, provided they are applied well and on time.

But keep in mind that many chemicals are toxic to beneficial insects, pollinators, and fish, so use them with caution!

Insatiable Critters Can Be Tough to Control

An insect like the beet armyworm, with a taste for nearly every crop you may want to plant in your garden, presents quite the adversary.

Add in a few complicating factors, including pesticide resistance, and these voracious pests can seem unstoppable.

Luckily there are a few options available, including some cultural, physical, biological, and, if necessary, chemical methods of control.

Have you ever encountered these ever-hungry larvae, chewing their way through your plants? Which vegetable did they seem to prefer, and how did you deal with them? Let us know in the comments below!

And if the beet armyworm isn’t your only veggie threat, read about other plant-munching larval pests, starting with these:

This season I planted tomatoes, peppers, peas, and kale. The army worms seem to love the kale. So much so that I’m tempted to surrender the kale to them for the sake of the other plants, but I’m sure this would be a short-sighted approach. I’ll try your suggestions.

Good luck! Let us know how it goes.