Prunus hybrids

Some of the best things in life spring from the fusion of two beloved favorites.

Think of the culinary delight when East meets West on a plate, or the thrill of a science fiction novel intertwined with a mystery.

Recall the fun of sporty sneakers transformed into a high-fashion statement and the entertaining combo of a heartwarming, yet funny rom-com on the big screen.

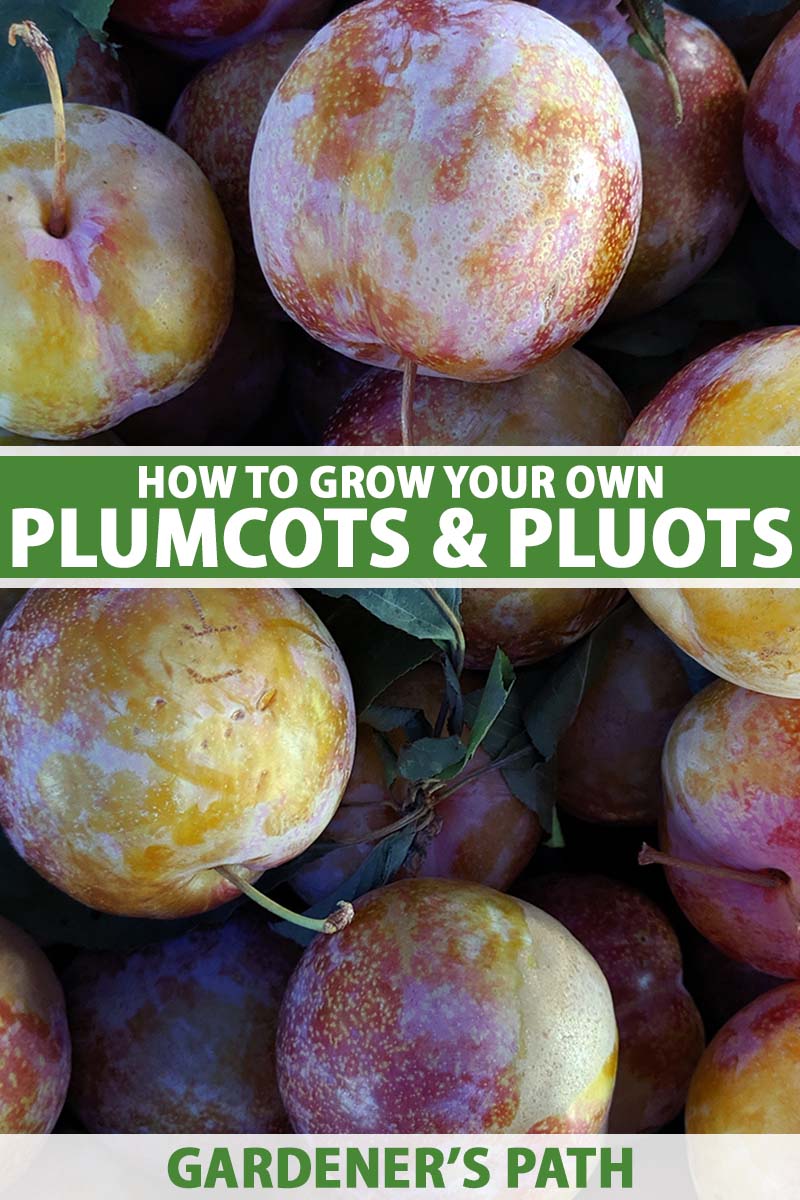

Well, in the world of fruits, we have our own blockbuster pairings: the plumcot and the pluot.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

These sensational hybrids marry the nostalgic charm of plums with the sweet elegance of apricots, crafting a taste that’s as unforgettable as any cross-genre classic.

Intrigued? Let’s explore the orchard’s most harmonious mash-ups and discover how you can cultivate these interspecific hybrid fruits in your own garden!

Here’s what I’ll be covering in this article:

What You’ll Learn

These aren’t your great-grandmother’s traditional orchard trees, but rather, high-performance hybrids of the modern fruit world.

Curious about how to add these to your garden? Keep reading to discover their juicy secrets!

What Are Plumcots and Pluots?

Plumcots and pluots are born from the hybridization of various cultivars (cultivated varieties) of plums and apricots, which both belong to the genus Prunus.

The terms “plumcot” and “pluot” are two simple portmanteaus of “plum” and “apricot.”

Plumcots are a 50-50 hybrid of these two fruits. Pluots contain more plum genes than apricot, usually around 60 to 75 percent plum and 25 to 40 percent apricot.

There are several species of plums, such as P. domestica (European plum), P. americana (American wild plum), and P. salicina (Japanese plum), among others.

Japanese plums are often used in modern hybridization efforts due to their hardiness, sweet flavor, and juicy texture.

The most commonly cultivated species of apricot is P. armeniaca, the common apricot. This species is typically used in hybridization efforts for creating plumcots, pluots, and apriums.

The hybridization process within this genus has evolved over the years. The original plumcot, developed by Luther Burbank, was a simple 50-50 hybrid of plum and apricot.

However, modern pluots, as popularized by the Zaiger family and other breeders, involve more complex and repeated cross-breeding.

I’ll dive deeper into the origin story and the breeders later. But for better context, I’ll give an example of the hybridization process first.

To create a pluot, plant breeders might cross a common apricot with a Japanese plum to create an initial hybrid, a plumcot. Then they might take this plumcot and cross it with another plum to get a fruit with a higher plum-to-apricot genetic ratio, a pluot.

They could take it even further and perform crosses with other selected varieties to achieve desired traits in terms of flavor, texture, appearance, and other qualities. This iterative breeding process allows for a vast range of flavor profiles, looks, and textures in the resulting fruit.

Because of this intricate process, and the vast number of potential combinations of various plum and apricot cultivars, pluots and plumcots come in a wide array of varieties, each with its own unique characteristics.

Plumcots and pluots, like their parent fruits plums and apricots, are best suited for temperate climates. They require a certain number of chilling hours, or hours with temperatures below 45°F (7°C), during the winter to break dormancy and promote flowering in spring.

However, the exact chilling requirements and the best USDA Hardiness Zones can vary from 250 to 800 hours depending on the specific variety of plumcot or pluot. Generally, these trees thrive in USDA Hardiness Zones 5 to 9.

Plumcot and pluot trees typically have an upright, spreading habit. At maturity, depending on the variety and growing conditions, these trees can reach heights of 15 to 20 feet with a similar spread.

One of the most attractive phases for plumcot and pluot trees is early to mid-spring when they burst into bloom. The trees produce an abundance of blossoms, often before the leaves appear.

The flowers are typically white to light pink and resemble those of both plums and apricots. Following flowering, leaves emerge, typically with an elliptical shape. The foliage is usually medium to dark green.

Small green fruits form after the flowers have been pollinated, gradually growing and changing color as they mature and ripen.

Depending on the cultivar, some fruits may have smooth skins, while others might be slightly fuzzy, and colors can range from yellow and green to deep purple or reddish hues. Some fruits are ready to harvest as early as mid-June, some in the summer, and others as late as October.

The trees maintain their lush green canopy throughout the summer. Some plumcot and pluot varieties can offer beautiful fall color, with leaves turning shades of yellow, orange, or even red before they drop. However, not all varieties will provide significant fall color.

After leaves drop in the fall, plumcot and pluot trees reveal a skeletal structure.

While they might not offer significant winter interest in the way some ornamental trees might with unique bark or persistent berries, their bare branching patterns can still be visually pleasing, especially when frosted or adorned with a soft layer of snow.

The dormant period of winter is essential for the tree to undergo the chilling hours necessary for bud break and flowering in the following spring.

In addition to their aesthetic appeal, plumcot and pluot trees can also provide habitat and food sources for various types of wildlife, especially pollinators during the spring bloom.

Now that you have a basic understanding of these fascinating fruit trees, let’s take a trip down memory lane to learn how they came into existence.

Cultivation and History

The history of the commercialization of plumcots and pluots in America can be traced back to the pioneering work of Luther Burbank, an American botanist and horticulturist in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Plumcots predate pluots, so we’ll begin the story there. The exact date of the first successful plumcot hybridization is a bit hazy, but it’s widely acknowledged that Burbank was tinkering with these hybrids in the late 19th century at his experimental farms in Santa Rosa, California.

Burbank’s work aimed to capture the sweetness and texture of apricots and the juiciness, texture, and varied flavors of plums. Through careful hand pollination, Burbank crossed the apricot and plum successfully.

This kind of hybridization involves transferring pollen from the flower of one species (say, the apricot) to the flower of another closely related species (the plum) and then waiting to see what kind of fruit results.

Burbank managed to successfully crossbreed plums and apricots to produce the plumcot, but it didn’t achieve widespread commercial success due to various challenges, including inconsistent fruit quality.

However, it laid the groundwork for future breeders to create further hybridizations such as the pluot, which did find significant commercial success.

The development of the pluot can be credited to Floyd Zaiger, a noted fruit breeder, and his family’s breeding program at Zaiger Genetics in Modesto, California, during the late 20th century.

Floyd saw potential in refining the plum and apricot hybridization process and set out to create fruits that combined the best attributes of their parent species including improved flavor, attractive color, resistance to disease, and extended shelf life.

The Zaiger family’s work was characterized by complex hybridization techniques. To develop the pluot, they did not simply stop at the initial hybridization of the plum and apricot.

Instead, they backcrossed the hybrid with plums multiple times to achieve fruits that contained up to 75 percent plum and 25 percent apricot in their genetic makeup.

This genetic ratio meant that pluots had more of the plum’s characteristics but retained some of the apricot’s sweetness and other qualities. The Zaigers patented the name “pluot” and were responsible for introducing several varieties of this fruit.

Over the years, the Zaigers and other breeders developed numerous pluot varieties, each with its unique flavor, texture, and appearance. This led to the increased popularity of pluots in grocery stores and farmers markets.

Some of the most popular pluot varieties include the Dapple Dandy®, Flavor King, and Flavor Queen, among others.

The success of the pluot led to the creation of other hybrid fruits, including the aprium, which is more apricot than plum, and several others, all of which offer unique flavors and textures.

It’s worth noting that the names “plumcot,” “pluot,” and “aprium” are sometimes used interchangeably in casual conversation, but they are distinct in their genetic makeup and breeding history.

In summary, while the idea of crossing plums and apricots has been around for a long time, modern-day plumcots and pluots owe their existence to the breeding experiments of dedicated horticulturists like Luther Burbank and Floyd Zaiger.

These fruits are a testament to the possibilities of selective breeding and the ever-evolving world of fruit cultivation. And speaking of breeding and cultivation, let’s take a closer look at the possible ways to propagate these fruit trees at home.

Plumcot and Pluot Propagation

Although it’s possible to grow plumcots from seed and it might be a fun experiment to try, it’s not a reliable method if you’re serious about growing these trees.

The seed is inside the stone, or what some people call the “pit,” found in the center of the fruit.

Growing these hybrids from seed has its challenges and considerations. In general, it can take several years before a tree grown from seed will produce fruit.

Plus, the seed will contain a mix of genetic material produced via sexual reproduction, so the fruit produced by a tree grown from seed will likely be very different from the fruit from which the seed was taken.

In comparison, scions grafted onto specific rootstocks often benefit from increased disease resistance or other favorable characteristics imparted by the rootstock in addition to producing fruit with identical qualities to the parent plant.

Grafting is usually done in late winter to early spring. The procedure involves taking a scion, which is a shoot or bud from the desired tree, and attaching it to a rootstock.

Both the scion and the rootstock are carefully cut to create matching “tongues” that lock together. The key is to ensure that the cambium of both parts, or the layer right under the bark, align perfectly.

Once joined, the union is tightly bound with grafting tape or raffia to secure the connection. The graft point must be monitored for callus formation, indicating a successful graft.

When grafting, it’s important to use healthy plant materials and a sterilized sharp knife to make precise cuts so that the surfaces meet seamlessly. If a graft fails, it’s often because of poor alignment or use of low-quality plant materials.

If you’re interested in grafting and budding, you can learn more and experiment in your home gardens or orchard. Courses might be a good idea for beginners to master this skill.

It’s also possible to propagate these fruit trees by rooting cuttings, and you can read more about it in our plum growing guide.

But if you’re interested in obtaining a healthy and reliable plumcot or pluot to start with, it’s generally best to buy a grafted tree from a nursery.

This ensures that you’re getting a tree that will produce the desired fruit and have other known characteristics such as size and disease resistance obtained from its hardy rootstock.

Here are the steps to follow for transplanting bare root and potted trees:

Transplanting

Before I dive into transplanting, let me give you the scoop on two important things: fungi and spacing.

I typically recommend incorporating mycorrhizal fungi into the soil when planting new fruit trees.

Healthy, established tree roots form a symbiotic relationship with mycorrhizae already present in the soil. This fungus colonizes the root system and helps the roots absorb nutrients and water to efficiently supply the tree with everything it needs.

When planting a new tree there is often little to no beneficial fungi present to give it a good start.

You can help your new tree out by adding the correct type of beneficial mycorrhizae at the time of planting.

You can find different products containing inoculants at your local nursery or online. I like this product called Root Build 240, sold by Arbico Organics.

Learn more about using soil inoculants in our guide.

If you choose to incorporate soil inoculants or any other product into your planting method, remember to read the label carefully.

Now let’s talk about spacing between these trees.

You’ll want to plan ahead for two reasons: to give your trees a minimum amount of space to grow to their full size without crowding and also to achieve successful pollination.

Depending on the cultivar you’re planting, the recommended minimum distance between plumcot and pluot trees is 12 to 20 feet. You can plant them further apart if you’d like, but not too far! Don’t forget about cross-pollination.

Cross-pollination is a requirement for producing a harvest. Another pluot or a Japanese plum can serve as a pollinator, but it’s crucial to plant these trees within 50 feet of each other to ensure successful pollination.

Now that I’ve given my speech on fungi and spacing, let’s get to planting!

Your pluot or plumcot could be a bare root or container-grown specimen. Start by preparing your hole for transplanting.

Dig a hole deep enough to accommodate the bare roots or root ball, and twice as wide.

Next, remove your tree from its bag, wrap, or container. Locate the graft point. It will resemble a crooked knob above the roots.

Identifying this graft point is important. You’ll want to make sure this knob sits about one to three inches above the existing grade or soil level after the hole is backfilled.

As a guide while planting, I like to place a stick or the handle of a shovel across the hole before backfilling to visualize the grade line against the trunk.

For bare roots, make a small mound of soil in the bottom of the hole and spread the roots out over it so they angle outwards and slightly down.

For potted trees, inspect the root ball. Tease out and loosen roots that are pot bound and trim off any damaged roots.

Set the root ball in the hole. Ensure the roots are spread naturally and not twisted or cramped in their new home.

Before backfilling, check the graft point and adjust the height if necessary. You can add soil or dig some out to get just the right planting depth.

When you’re satisfied with the placement, backfill the hole around and on top of the roots, tamping down gently to squeeze out any air pockets.

Water the new tree thoroughly after planting. I like to wait about 10 minutes and if the water is all absorbed, I water again.

Now is a good time to add a layer of mulch. I’ll discuss more details on this later, so keep reading.

I stake my new trees for at least a full year until they’re established. It helps to protect them by keeping them stable while their roots are becoming established.

If you share your space with wildlife, it’s smart to install a tree guard to discourage critters from chewing on the young and tasty flesh of the tree’s trunk.

These guards come in different shapes and sizes, and you can even fashion a guard from materials like chicken wire.

I like guards with a spiral design because they’re easy to install and remove, and they expand with the tree as it grows.

Check out this Upgrade PCS Trunk Protector sold by Ugarden on Amazon.

How to Grow Plumcots and Pluots

Plumcots and pluots thrive in full sun, preferably in south-facing or west-facing locations.

It’s essential to choose a sheltered site for these trees, especially one that offers protection from prevailing winds.

The soil for these fruit trees should drain well, and it’s advisable to avoid areas with heavy clay or overly sandy soils.

The ideal pH level for the soil should be slightly acidic to neutral, ranging from 6.0 to 7.0. If the soil lacks essential nutrients, it can be amended with organic matter to enhance its fertility.

Not sure what the makeup of your soil is? Conduct a soil test before you plant.

Watering is crucial, especially for newly transplanted trees.

During their first growing season, they should be watered deeply at least once a week, with each tree receiving about three to four gallons of water.

It’s essential to ensure that the soil remains moist but is well-drained to prevent root rot.

To retain moisture and suppress weeds, a two- to three-inch layer of organic mulch should be spread around the base of the tree, extending about three to four feet from the trunk.

This can be done in the spring or fall, but remember to keep the mulch a few inches back from the base of the tree, so it doesn’t touch the bark.

Growing Tips

- Choose a sheltered location with full sun.

- Plant in well-draining soil with a pH of 6.0-7.0.

- Amend the soil with organic matter to enhance fertility.

- Plant another pluot or Japanese plum to promote cross-pollination.

Pruning and Maintenance

Plumcots and pluots require regular pruning to maintain a healthy structure and promote fruit production.

Most are Japanese plum hybrids, so you can follow the same recommended techniques as you might for these trees.

You’ll find in-depth details for pruning Japanese plums (P. salicina) in our guide, but these are some basic guidelines:

Annual pruning of both new and established trees is essential and should be carried out in late winter or early spring when trees are dormant.

Use the open center system. Also referred to as open vase, this involves selecting three to four main branches growing 24 to 30 inches off the ground in different directions and removing the central stem entirely.

Begin by removing any dead, diseased, or damaged branches. Established trees should have about 25 percent of their branches removed to allow light penetration, which increases fruit quality and encourages new branch development.

Like plums, plumcots and pluots produce most of their fruit on short spurs on wood that is two to five years old, but they also produce some fruit on the basal buds of one-year-old wood.

Regular removal of suckers, or shoots coming from the roots or stem below the graft, is also necessary.

In terms of fertilization, there are no specific recommendations for homegrown plumcots and pluots. However, you might want to monitor the growth rate of your trees and fertilize based on your observations.

Trees under five years old should produce new shoots averaging 10 to 20 inches in length each year and older trees should have a growth rate of eight to 10 inches of new growth per year.

If these growth rates are not achieved and you’ve eliminated other causes like poor irrigation, poor drainage, pests, and diseases, consider fertilizing.

Test your soil to see which nutrients are lacking and remember that excessive fertilization can be harmful, so it’s crucial to monitor the tree’s growth and adjust accordingly.

To ensure larger and better-quality fruits, it’s advisable to thin the fruit when they’re about the size of a dime. This process involves removing excess fruits, leaving about one fruit every four to six inches.

Regularly cleaning up fallen fruits and leaves can help reduce the risk of disease and infestation. This practice is especially important in the fall to prevent overwintering of certain pests and disease pathogens.

Following some routine maintenance guidelines and paying attention to your trees’ needs will result in a bountiful harvest.

Plumcot and Pluot Cultivars to Select

Plumcots and pluots have desirable ornamental value aside from their food production. The hypnotic fragrance of their adorable spring blooms make them excellent additions to home gardens and orchards.

It’s a good idea to research and select a variety based on your specific region’s average number of chilling hours and climate conditions.

Before planting, always consult local nurseries or agricultural extensions for advice on the best varieties for your region.

These experts can provide insights into which specific cultivars of plumcots and pluots are most likely to thrive in your local conditions and give you more details about chilling hours, pollinators, and planting.

Keeping in mind that plumcots are usually equal parts plum and apricot while pluots lean more toward the plum family, take a look at these popular varieties to consider planting in your own space.

Dapple Dandy

The Dapple Dandy Pluot® (Prunus ‘Dapple Dandy’) is a fun and tasty option for the whole family. This tree is suited for Zones 5 to 9 and reaches 15 to 20 feet tall.

‘Dapple Dandy’ is sometimes called Dinosaur Egg because its fruit has a spotted appearance and mottled skin coloring.

The smooth, shiny skin closely resembles a plum. Its greenish-yellow, red-spotted exterior develops into a maroon and yellow dapple as it begins to ripen.

With a moderately late harvest, this variety can be pollinated by the ‘Santa Rosa’ plum.

This tree requires about 400 to 500 chilling hours. You can order a four- to five-foot-tall potted sapling to transplant into your own garden at Nature Hills Nursery.

Flavorella

The ‘Flavorella’ plumcot tree reaches a height of 15 to 18 feet at maturity and is suited for USDA Zones 7 to 10.

This tree produces fruit characterized by its beautiful golden yellow skin with a faint red blush. When ripe, the medium-sized fruit is very sweet and incredibly fragrant.

The flesh of the fruit is juicy and firm with a yellow hue. The flavor is described as a harmonious mix of a super sweet apricot with a touch of full-bodied acidity from the plum.

When it comes to pollination, it’s recommended to plant this type with a ‘Santa Rosa’ plum, ‘Gold Kist’ apricot, or another plumcot nearby.

‘Flavorella’ requires 500 to 600 chill hours and you can find it at Nature Hills Nursery.

Flavor King

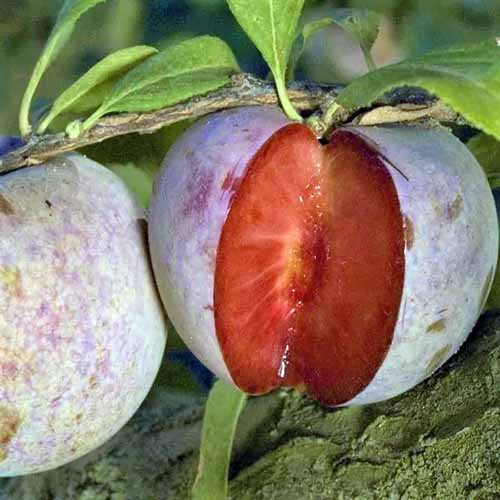

The Flavor King Pluot® is recognized for its deep red flesh and intense, sweet flavor.

Reaching a mature size of 12 to 20 feet, Flavor King® is perfect for home gardens. Once established, it’s low maintenance and thrives in USDA Zones 5 to 9.

This tree requires about 400 to 500 chilling hours and a pollinator such as ‘Burgundy’ plum, Dapple Dandy, or ‘Methley’ plum.

The fruit matures in mid- to late August and will typically remain firm on the tree for a few weeks, so there is no rush to pick them.

Find Flavor King® at Fast Growing Trees.

Geo Pride

The ‘Geo Pride’ tree reaches a height of 12 to 15 feet and is hardy in USDA Zones 6 to 9.

In the spring, it showcases fragrant white blooms, attracting bees and butterflies. Despite its smaller stature, the tree is highly ornamental and can be a focal point in any garden.

The fruit it produces has a smooth golden yellow and reddish-purple mottled skin, complemented by golden yellow flesh. The flavor is a harmonious mix of plum and apricot, and the fruit has a crisp texture.

The fruit matures in mid-season and is medium-sized.

For successful pollination, it’s recommended to plant Geo Pride near other pluots or other compatible pollinators such as Dapple Dandy® or ‘Flavor Supreme.’

This tree requires about 400 chill hours. Plants are available at Nature Hills.

Splash

The Splash Pluot® tree produces small to medium-sized yellow to orange colored fruit that boasts super sweet and juicy flesh.

It reaches a height of 15 to 25 feet and is hardy in USDA Zones 5 to 11.

The tree requires about 400 chill hours and fruits are typically ready to harvest in July. Splash Pluot® plants are available at Nature Hills.

Managing Pests and Disease

Management of pests and disease is critical to growing any plants successfully, but this is especially important when you’re aiming to achieve food production with fruits like the pluot or plumcot.

Herbivores

Plums are a favorite for deer, mice, and rats, usually when they’re ripe, but sometimes even before they’re fully ripe.

And from personal experience, I can tell you that bunnies are known to nibble at the tender trunks of young trees. If you share your garden with wildlife, take this into account and plan ahead.

To deter deer from snacking from low branches, plant your plumcots and pluots in a protected area or consider installing a fence around them.

Pick up fallen fruit from the ground to discourage small rodents like mice and rats from setting up camp in your yard.

And if you’ve spotted bunnies hopping through your grounds, think about adding a cage or wrap to the trunks of young trees.

Insects

Insects that target plum trees will also prey on plumcots and pluots. These include aphids, peach tree borers, plum curculios, and scale insects.

Insects can carry disease, so it’s important to stay on top of infestations before they get out of control.

Disease

Diseases common to plums will also attack plumcots and pluots. Look out for black knot, brown rot, and silver leaf fungus.

Regular monitoring and early intervention are crucial. It’s essential to maintain good sanitation practices, like cleaning up fallen fruit, to reduce disease risk.

Harvesting and Storage

Plumcots and pluots are typically ready for harvest from mid-June to early July, but some varieties will extend the season into fall.

Check your chosen variety for more information about when to harvest.

The best indicator for harvesting is when the fruits are plump and exhibit rich coloration. Gently squeeze the fruits to feel how firm they are. They shouldn’t be too firm or too soft for perfect ripeness.

Japanese plums are revered for eating fresh, and in my house, they disappear quickly.

Since pluots and plumcots are in the same family, follow storage recommendations similar to what you would do with plums.

Once harvested, these fruits can be stored for later use. If you’re planning to use them within three weeks, store them in a cool and humid environment, ideally between 32 and 40°F (0 and 4°C).

If you’re storing them in a refrigerator, it’s the perfect environment. However, when you’re ready to consume them, bring the fruits out and let them return to room temperature first. They’ll taste better this way!

Enjoy your plumcots and pluots throughout the winter by freezing them. Remove the pits and slice into chunks.

Place the chunks on a cookie sheet or tray and put them in the freezer to freeze individually, without touching each other.

Once frozen, transfer the fruit to freezer bags and store for up to eight months.

Recipes and Cooking Ideas

These fruits are best known for eating fresh, but similar to plums, they can also be processed into jam, jelly, and can be dehydrated to make fruit leather.

To make your own fruit leather, try this recipe from our sister site, Foodal.

Showcase your freshly harvested fruits in a simple summer salad, and make them the main attraction.

Toss in some toasted ginger, garlic, and some fresh herbs like mint, basil, or cilantro to make it more savory. Add a squeeze of citrus and a dash of soy sauce and you’ll be in heaven.

Of course, you can bake a simple crisp using these fruits. But why not try something new? Galettes are one of my favorite rustic desserts.

Not only are they delicious, but they make an impressive presentation when served to guests. Let them think you spent hours working on it!

Most any fruit can become the star of the show here, but plumcots and pluots would be absolutely brilliant. Find a fantastic recipe for this dessert on Foodal.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Deciduous fruit tree | Water Needs: | Moderate |

| Native to: | Cultivated hybrid | Maintenance: | Moderate |

| Hardiness (USDA Zones): | 5-9 | Tolerance: | Some drought |

| Bloom Time/Season: | Spring blossoms, spring/summer/fall fruit | Soil Type: | Loamy |

| Exposure: | Full sun | Soil pH: | 6.0-7.0 |

| Time to Maturity: | 3-7 years | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Spacing: | 12-20 feet | Attracts: | Bees, butterflies |

| Planting Depth: | Same as growing container (transplants), graft point just above the soil, crown just below the soil (bare roots) | Avoid Planting With: | Black walnut |

| Height: | 12-20 feet | Family: | Rosaceae |

| Spread: | 12-20 feet | Genus: | Prunus |

| Common Pests and Diseases: | Aphid, deer, mice, rabbits, rats, plum curculio, scale, wood borer; brown rot, black knot, silver leaf | Species: | Hybrids |

Perfectly Orchestrated Duets

We’ve journeyed through the orchard’s melodious blend of plums and apricots, arriving at the plumcot and the pluot.

Here, we have two blockbuster duets, showcased by nature with some production assistance from humans.

Now, step out into your garden and envision it as a stage where the magic of plums and apricots come together in one delightful specimen.

Try one, try both, or try any other stone fruit hybrids you might find locally that are suited for your Zone.

I’ve covered the history of these fruit trees and all the necessary information you need to know to grow them. I’ve even given you a few suggestions for cultivars to get you started.

I’m hunting for a companion pollinator for my own plumcot now in Zone 5b. Let’s hunt together! Which trees are you considering or which are you already growing? Please share in the comments below.

If you’re interested in growing food-producing trees, you might be interested in reading these articles next: