Autumn is my favorite season – crisp, fresh, and full of promise. I want to wear plaid, sharpen pencils, and buy a new journal.

Each year I eagerly anticipate leisurely walks among the brilliantly colored foliage that dots my local landscape.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

Birches, Betula spp., and tulip poplars, Liriodendron tulipifera, are awash in yellow.

Maples, Acer spp., staghorn sumac, Rhus typhina, and Virginia creeper, Parthenocissus quinquefolia, turn a fiery scarlet.

And the multihued orange, purple, red, and yellow oakleaf hydrangeas, Hydrangea quercifolia, are rivaled only by the equally diverse hues of sassafras.

Over the years there have been many truly dazzling displays, but sometimes the palette is more muted. I wondered if I really knew why, so I explored the life cycle of a leaf.

In this article, I’ll tell you what I learned about why leaves change in the fall. You may be surprised to discover that even scientists don’t fully comprehend the phenomenon.

Here are the topics we’ll cover together:

What You’ll Learn

Let’s get started.

Green and Growing

Woody perennial shrubs, trees, and vines that drop their leaves are described as deciduous, as opposed to evergreen.

Green foliage looks green because it contains a pigment called chlorophyll that doesn’t absorb green light.

During a plant’s life, it absorbs carbon dioxide and water and transforms them into food via photosynthesis.

Photosynthesis is a two-step process that takes place inside chloroplasts, microscopic organelles or structures within the cell walls of plants. The first phase is light-dependent. The second phase, or the Calvin cycle, is light-independent.

During the first phase, light absorption creates two chemical coenzyme molecules, NADPH and ATP. During the second, it uses their energy to produce glucose, the sugar plants need to survive.

To grow, flower, produce fruit, and set seeds, a photosynthetic plant needs to continually feed itself via this process. But as the growing season draws to a close among deciduous species, the need for food diminishes.

Winding Down

With the approach of fall, the days grow shorter. As the nights lengthen and grow cooler, the leaves absorb fewer nutrients, and chlorophyll production slows down.

As the manufacture of food slows down, deciduous plants absorb the remaining chlorophyll.

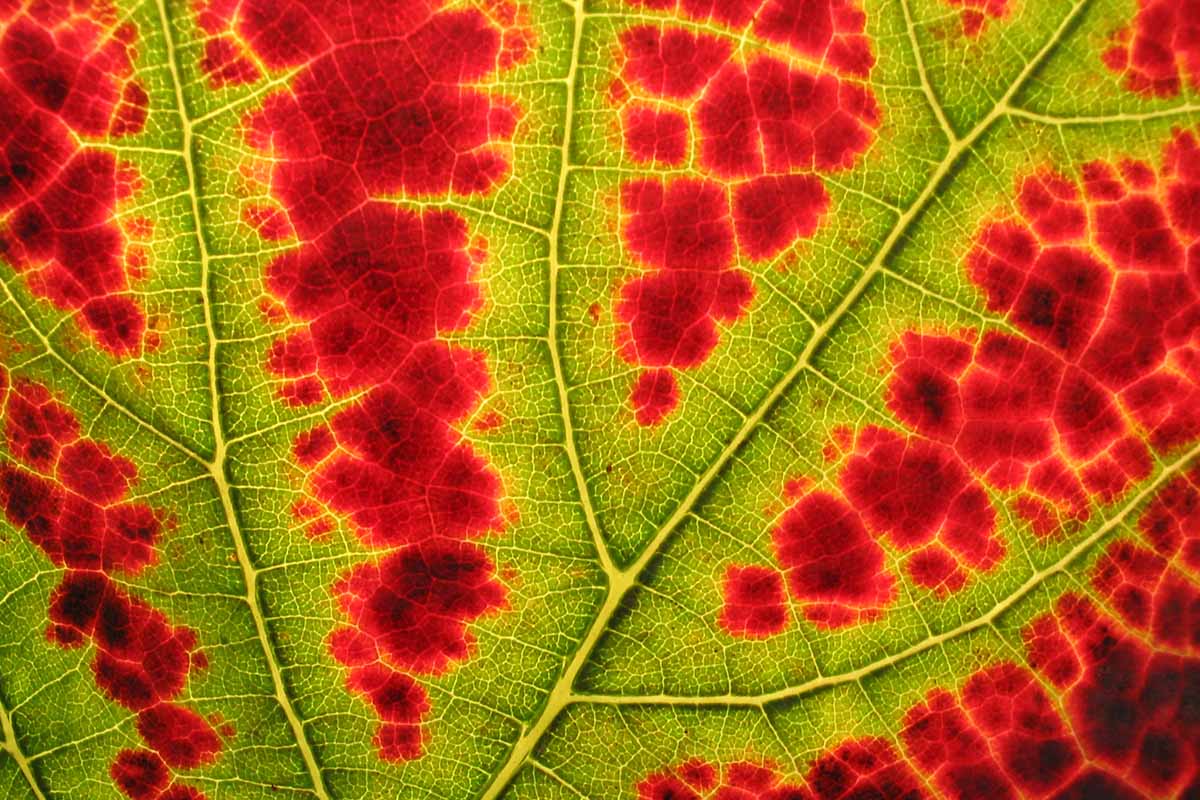

Gradually, the green color reveals accessory pigments that were masked by the presence of chlorophyll, including brown tannins, orange carotenoids, yellow xanthophylls, and red anthocyanins.

These pigments reveal themselves to produce a glorious end of season show.

In addition to reducing chlorophyll production and changing colors, a deciduous plant prepares to drop its leaves for winter dormancy.

To do this, it grows new cells at the point where the petiole or stem will separate from the main branch. They form an abscission layer or zone.

The cells block the leaf veins, causing them to retain sugar and produce anthocyanins, the red pigments. When the abscission layer is complete, the leaf is sealed off from the branch and ready to be released.

Per the USDA Forest Service, leaf cycle timing seems to be genetically determined and does not vary by geographical location. For example, no matter where you are, oaks are one of the last species to change color at the end of the growing season.

Some species, like the pin oaks, Quercus palustris, growing in a park near me, hold onto their leaves until the following spring.

This behavior is called marcescence and occurs in species that do not produce abscission layers. Other marcescent trees are beech, Fagus spp., and hornbeam, Carpinus betulus.

Contributing Factors to Leaf Color Change

In addition to extended periods of darkness, cooler nights, and underlying pigmentation, weather and moisture play critical roles in creating autumn’s rich tapestry.

When rainfall during the spring and summer is adequate and there is no drought, biologists like Harold Neufeld, the “Fall Color Guy” of Appalachian State University, are optimistic about a superior showing.

However, when hot summer temperatures persist well into the fall, they not only delay the turning process, they contribute to a reduction in the brilliance of the colors plants display.

In North Carolina in 2017, such temperatures prevailed, resulting in primarily oranges and yellows.

Wind and rain are additional factors detrimental to a grand display. Leaves may detach prematurely with strong gusts and downpours.

Also, on cloudy and rainy days, the production of sugar essential for red anthocyanin pigment production is reduced, and the colors already revealed show poorly.

Finally, an early frost may wipe out expectations of magnificent color because it prevents pigments from reaching their peak or kills the leaves altogether.

The ideal weather conditions during the photosynthesis slowdown are dry and sunny days, and cool nights without frost.

Theories Under Consideration

As you can see, there is much we know about why foliage changes color.

However, scientists are not convinced they have the whole picture. Ongoing research includes the effects of climate change on fall foliage and pigmentation as an herbivore deterrent.

In 2001, evolutionary biologists W. D. Hamilton and S. P. Brown suggested that autumn leaves could be a “handicap signal” that warns insects of toxic chemical contents and acts as a deterrent.

It is referred to as a handicap, because it is an “honest” or non-disguised defense mechanism that comes with a cost to the tree – a reduction of chlorophyll in exchange for bright, insect-deterring colors.

The diversity of color may be the result of a tree’s targeted defense against particularly aggressive pests.

Their focus was on aphids, pests that use color as a cue when selecting host foliage, like maple trees.

Similarly, a 2011 study determined that tannins defend against insect pests because of their deterrent and/or toxic properties.

Another study in 2020 turned scientists’ expectations upside-down.

It revealed that while global warming is lengthening the growing season and leaves are sprouting earlier and dropping later, a longer period of photosynthesis may actually contribute to earlier leaf drop over time.

And earlier dropping adversely affects forest trees’ ability to take up carbon dioxide, and contributes to climate change instead of helping to reduce it.

The fall leaf cycle is an exciting field of scientific study. I can’t wait to hear about the latest developments!

True Colors

In addition to being a botanical phenomenon, “leaf-peeping,” as it’s called, is a multi-billion-dollar industry.

When forecasters like Harold Neufeld predict a poor showing, popular viewing areas like New England and North Carolina face economic consequences.

Here in southeastern Pennsylvania, this year’s summer drought is robbing us of a showy fall.

While most of the larger trees are still green, some smaller ornamentals are turning orange, and others are already dropping yellow leaves. It is only August at the time of this writing, and our foliage usually peaks in October.

Autumn leaves not only reveal hidden colors, they paint a portrait of a planet undergoing change.

Take some time to appreciate nature’s exquisite palette. Plant perennial, deciduous woody shrubs, trees, and vines that are not only beautiful but create habitat for wildlife and promote cooling.

Let your outdoor living space reflect what you love and who you are.

If you enjoyed reading about the fall leaf cycle and want to introduce color to your late-season landscape, we recommend the following guides next: