Malus x domestica ‘Braeburn’

Whether you prefer apples for snacking, preserving, baking, or juicing, ‘Braeburn’ answers the call. Prepared in all imaginable gastronomic ways, this cultivar does not disappoint.

Not only has it earned five stars from me for eating, it also happens to please the eye.

The apple trees boast fragrant, delicate white flowers in the spring that are sure to call all the bees and butterflies to the yard.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

I’ve been fortunate to live in and near some of the best fruit producing regions in the United States and Canada – the Willamette Valley along the Columbia River Gorge, a stone’s throw from Washington State and the Okanagan Valley, and in microclimates along the shores of the Great Lakes like Niagara and Georgian Bay.

At the heart of these regions, you’re always sure to find outstanding apples. This fruit is a staple for farmers and for our diets.

So, it’s no surprise I’ve consumed one or two (thousand) over the years. It’s fair to say, I’m both a fan and a critic.

My fruit standards are high, and I don’t go around promoting particular varieties willy-nilly. To put my stamp on a fruit, that baby better take my breath away.

So, when I say it’s good, trust me – it’s good. And this one is better than good, better than great. ‘Braeburn’ apples are quite possibly perfect.

Plant a ‘Braeburn’ apple in your garden and you’ll be the envy of your neighbors. Share the fruit with them and they’ll be your friends for life.

I’ll explain all you need to know about growing this special tree. Here’s what’s ahead:

What You’ll Learn

Let’s get to know this ‘Braeburn’ a little better.

What Are Braeburn Apples?

‘Braeburn’ is a cultivar of the domesticated apple, a member of the genus Malus, which contains about 35 species of deciduous trees and shrubs from Europe, Asia, and North America.

‘Braeburn’ was discovered in New Zealand. I’ll explain more about that story later.

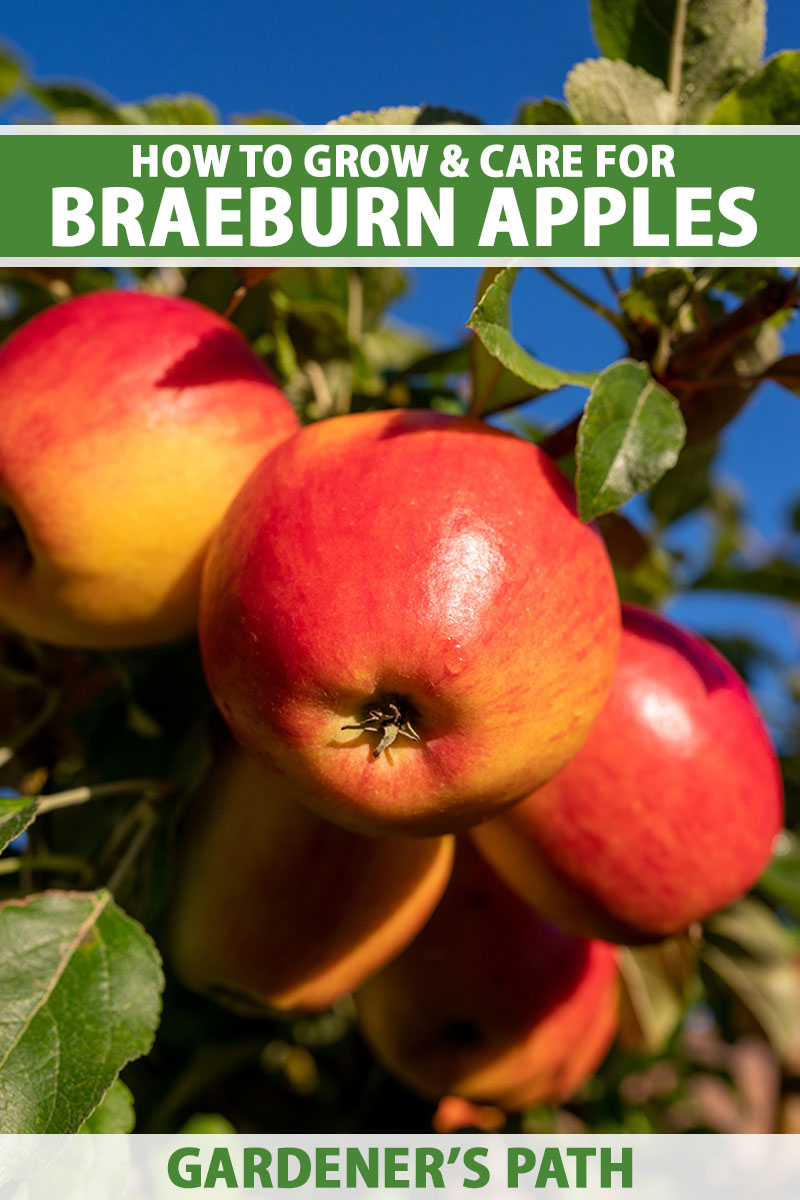

This cultivar is popular for its taste, high yields, and its beauty. Each spring it awakens with delicate white blossoms, followed by large, bountiful fruits.

Although the blossoms and foliage of ‘Braeburn’ are quite attractive, its ornamental characteristics are considered by many to be secondary to its production value.

The apples are usually medium to large in size, with color that varies from greenish-gold with hints of red blushing to solid red.

‘Braeburn’ apples offer a satisfying balance of sweet and tart with a firm texture, making them suitable for snacking and cooking in everything from ciders to sauces, and baking to freezing.

These trees thrive best in moderate to warm climates, and grafting on different rootstocks provides choices for gardeners in USDA Hardiness Zones 4 to 9 who may have different space requirements or cultivation needs.

As with many favorite fruit trees in North America, the ‘Braeburn’ apple has a spotty origin story. Read on to learn what we know about its past.

Cultivation and History

‘Braeburn’ was discovered in New Zealand in 1952 as what is known as a “chance seedling” – an unintentionally planted specimen.

A farmer named Moran spotted the tree in a fenceline on his farm in Motueka, Nelson region, back in 1952.

For context, the growing conditions there are roughly equivalent to that of USDA Zones 9b to 10a.

Moran didn’t recognize the apples growing on this rogue specimen, so he picked one and brought it to Williams Brothers nursery, near the town of Braeburn, for identification.

The nursery owners suspected the fruit was a cross between ‘Lady Hamilton’ and ‘Granny Smith,’ although a recent genetic study has identified the most probable parents as ‘Delicious’ and ‘Sturmer’s Pippin.’

Williams Brothers grafted cuttings from the tree onto their own rootstock and began cultivating its offspring in their orchard on Braeburn road.

Some years later, Williams Brothers gave the cultivar to what was then the Apple and Pear Board of New Zealand. Neither the Moran family nor the Williams brothers have ever received a royalty for the discovery and cultivation of this popular variety.

‘Braeburn’ apples were introduced to the US in the 1980s and have become a favorite for many reasons.

Happily flourishing in USDA Zones 4 to 9, they’re relatively fuss-free and easy for growers to manage.

They also happen to be delicious for snacking and perfect for cooking and baking, versatile beyond belief.

So, whether we’re talking about producers, consumers, or sellers – everyone loves them. And my bet is you probably will too.

Braeburn Apple Propagation

When propagating apple trees, most growers use grafting. This method is efficient and provides control over the desired genetics.

By grafting a scion onto a hardy rootstock, growers can produce clones that are identical to one another and to the parent plant.

Apple trees can also be propagated from softwood or semi-hardwood cuttings, and if you’re inexperienced with grafting you may want to experiment with cuttings without grafting onto sturdy rootstock of another variety.

You can take a cutting from a ‘Braeburn’ tree if you have access to one, and coax it to root. But this process can take up to six months, and the success rate is statistically low.

Enthusiastic home gardeners and urban farmers can perform their own grafting. But if you’re a novice, you’ll be better off purchasing young grafted specimens to transplant into your garden or home orchard.

‘Braeburn’ is commonly grafted onto dwarf or semi-dwarf rootstock, while some nurseries also offer standard rootstock with this cultivar.

Dwarf and semi-dwarf rootstocks are desirable for home gardeners since they’ll stay within manageable size tolerances for pruning and harvest.

I don’t know about you, but I’m not interested in climbing more than a few ladder rungs to pick an apple!

Not all rootstocks are suited for growing conditions in every Zone. I advise you to do some research before deciding or take the recommendation of your local nursery and don’t sweat over it!

Transplanting

Before we get started, let’s talk about fungi. If you’ve read my other articles, you know I usually recommend incorporating mycorrhizal fungi when planting new fruit trees. If you’re new here, I’ll give you the scoop.

Tree roots in their healthy, established habitats form a symbiotic relationship with mycorrhizae. The fungus colonizes the root system and helps the roots absorb nutrients and water efficiently.

When a tree is introduced to its new home, and this is especially true with bare roots, there is usually little to no fungus present.

But you can help the colony, and your ‘Braeburn’ tree, by adding beneficial mycorrhizae at the time of planting. Learn more in our guide about the benefits of using soil inoculants.

If you’re looking for a recommendation, check out this product called Root Build 240, sold by Arbico Organics.

If you’re thinking of trying a different product, awesome! But always read the label and talk with experts at your local garden center if you need to, to avoid incorrect usage.

Beginning with a bare root or container-grown specimen, prepare your hole for transplanting. Dig a large hole deep enough to accommodate the bare roots or root ball, and twice as wide.

Now, carefully remove your tree from its pot, bag, or plastic wrap. Identify the graft point. It will resemble a crooked knob above the roots.

Whether you’re planting a bare root or potted tree, you want to make sure the graft point sits about one to three inches above the existing grade or soil level after the hole is backfilled.

I like to place the handle of a shovel or a stick across the hole before backfilling to visualize the grade line against the trunk.

For bare roots, create a small mound in the bottom of the hole and spread the roots over the mound so they are angled out and slightly down.

In the case of potted trees, check the root ball. Loosen roots in specimens that are pot bound and trim any damaged roots.

Place the root ball in the hole. Ensure the roots are spread naturally and not twisted or tight in the hole.

Don’t plant too deep! Remember to check the graft line and adjust the height if necessary.

Backfill the hole around and on top of the roots, tamping down gently to ensure there are no air pockets. Give the little tree a good drink of water. I usually wait about 10 minutes and if the water is all absorbed, I water again.

Adding a layer of mulch is a good idea. Three to four inches thick is a standard recommendation. Avoid piling mulch against the trunk – leave a few inches of bare ground around the base.

This mulch will help conserve moisture and insulate young, delicate roots against extreme heat and freezing temperatures.

I usually stake my new trees for at least a full year until they’re more established.

This helps to protect them from high winds and accidental mishaps that may dislodge the roots. Trees that grow sideways can be fun to look at, but they’re not very practical.

The last thing I always do when planting a new sapling is install a tree guard. Tree guards come in different shapes and sizes, but their purpose is the same.

They protect the tree from animals like voles and rabbits who like to chew on the tender flesh of the trunks.

I use one with a spiral design like this Upgrade PCS Trunk Protector sold by Ugarden on Amazon.

I like it because it’s easy to put on and take off, which is nice if you want to inspect the trunk at any time. And it expands with the tree as it grows.

How to Grow Braeburn Apple Trees

Before you pick your first apple, your ‘Braeburn’ tree must be nurtured for two to five years to reach maturity.

During those years you should give it all the things it needs to thrive. Let’s take a closer look at these variables.

Soil

No matter what you’re growing, it always begins with the soil. ‘Braeburn,’ like most apple trees, prefers organically rich, loamy soil with a pH level of 6.0 to 7.0. And you’ll need to ensure good drainage.

Because apples need full sun for best performance, choose an open site, free from large-canopy trees that could cast too much shade.

You can sneak by with average soil, but if the site is mostly heavy clay, this could cause drainage issues.

You want to avoid standing water, so in this case it’s wise to elevate your planting area or choose a different site altogether.

Climate Needs

Due to its geographic origin, this cultivar enjoys warm climates. ‘Braeburn’ is suited to Zones 4 to 10, and as mentioned, it does best in full sun.

But to achieve the highest fruit production, take note that this cultivar requires about 700 chill hours. That’s approximately a month of temperatures in the range of 32 to 45°F.

This means, if the temperature in your Zone never drops for long enough, you’ll have a gorgeous green and healthy specimen, but you might not reap a substantial yield from it.

In this case, search for a better suited apple variety for your own climate.

Irrigation

After planting, and while your ‘Braeburn’ is settling into its new home, ensure adequate irrigation. If it’s a particularly dry season, you will need to supplement with regular watering.

While ‘Braeburn’ apples become more drought tolerant once they’re acclimated to and established in their new home, remember this doesn’t mean they’re drought-resistant. To remain healthy and productive, this variety needs regular watering.

If you’re unsure if your tree needs water, feel the soil. Poke a finger two inches deep in the root zone and if it feels moist, skip watering. If it feels dry, water!

For a broader explanation and more specifics, visit our guide to watering apple trees to learn more.

Summers in my area, in Zone 5b, have been particularly hot and dry in the last few years, so I invested in a drip irrigation system. I have four fruit trees and a few dozen large fruit shrubs.

Although I’ve got swales incorporated into my landscape, that doesn’t help much if there isn’t any rain.

If you’ve got more than one or two fruit-producing plants in your own yard, consider setting up a hassle-free irrigation system of your own.

It’s not difficult, and in the long run, it’s worth the initial investment of time and money.

Fertilizing

It’s best to avoid fertilizer for your tree’s first year in the ground. Concentrate on making sure it’s receiving the right amount of water.

Once the ‘Braeburn’ is more established you can think about a fertilizing routine. The best time to fertilize is in the spring when you see new growth beginning to show.

The worst time is from midsummer into fall. Fertilizing in the fall signals your tree to start growing at the wrong time.

A slow-release, organic fertilizer is a good option. Too much nitrogen can actually be detrimental, so take care not to overdo it.

For flower and fruit production, phosphorus is the most important element to focus on.

A well-balanced fertilizer specific to fruit trees, like Espoma’s Organic Tree-Tone, is a good option. You can find it at your local nursery or online at Nature Hills.

And, as always, be sure to test your soil and read all directions for use when using new products in your home garden.

All of our trees and gardens will be unique depending on our local conditions. Just because something works for me doesn’t mean it’s going to be the perfect choice for you.

Pollination

Pollination is a very important factor to consider when planting fruit trees if you want any kind of successful yield.

‘Braeburn’ trees are self-fertile, which is rare with apples. But it’s wise to plant a mate to ensure a reliable fruit set. Let me explain.

Most apple trees are not self-fertile. They need at least one, and sometimes two different kinds of trees nearby to pollinate them and bear fruit.

And depending on flowering time, this pollination process must be coordinated.

Trees fall into different pollination groups, categorized by their flowering times, and certain varieties are paired together to ensure the timing is successful.

Pollination groups may range from 1 to 7 and ‘Braeburn’ falls into group 4, which means its flowers are not the first or last to open.

Planting a backup cross-pollinator is a good plan and strengthens your chances of successful fertilization. In short, consider giving your ‘Braeburn’ a friend for company.

But what to choose? Look for trees from groups 3, 4, or 5. Here are a few to consider:

- ‘Delicious’ (Group 4)

- ‘Gala’ (Group 4)

- ‘Granny Smith’ (3)

- ‘Honeycrisp’ (4)

- ‘Northern Spy’ (5)

Fruit trees can be finicky when it comes to pollination and sometimes further investigation is warranted. If you’ve got an apple tree that isn’t bearing fruit, this could be the reason.

See our guide to pollinating apple trees for more information.

Guilds

Speaking of pollination, I’ll give you my single biggest tip for a successful fruit harvest: tree guilds.

If you’re familiar with permaculture design and techniques, or the concept of food forests, you probably know about guilds. But if this is new to you, I highly suggest learning more.

Guilds are the keystone for the ecological success of sustainable food production according to a permaculture model, and urban dwellings can be the best places for it.

Within your own backyard, you have the opportunity to create your own little ecosystem complete with all the layers necessary for growing your own food.

I won’t go into great detail about guilds here. You can read our guide to permaculture tree guilds to learn more.

But in short, think of it as companion planting taken to the next level.

Bulbs like garlic, onions, and daffodils work well. Herbs such as mint, thyme, lemon balm, and dill are useful and attract pollinators.

Comfrey, rhubarb, and artichokes are also perfect additions. Try clover for a low-maintenance ground cover.

If you introduce species to attract pollinators, herbs, and other plant pals to your apple’s environment, it will be in happy horticulture heaven.

Growing Tips

- Plant in a location with full sun.

- Ensure organically-rich soil with good drainage.

- Monitor soil moisture and water regularly.

- Introduce companion plants and build a healthy guild.

- Consider the addition of a cross-pollinating partner.

Pruning and Maintenance

Pruning promotes health, invigorates tired specimens, and encourages new growth and fruit production. Pruning while the tree is dormant promotes a sturdy base, while trimming in the summer controls excessive seasonal growth.

When your ‘Braeburn’ is dormant, remove bottom branches positioned 24 to 36 inches from the ground, crossed and overlapping branches, deadwood, dense interior branches, double leaders, and any branches with narrow crotch angles.

During the growing season, prune branches to control size and shape, and remove suckers and water sprouts. After performing these pruning tasks, finish by thinning the fruit.

Thinning fruit protects branches from becoming overloaded with weight and encourages the remaining apples to grow larger. Do this before the apples are the size of a dime.

When thinning, start by leaving only one fruit per spur (the spur is the woody structure where the flowers were formed).

Depending on the distance between spurs, you may want to remove fruits from spurs in between each other, leaving some spurs without fruit. Aim for about six inches or more between fruits.

Read our comprehensive growing guide for details and instructions for pruning apple trees.

Aside from pruning, you should pay attention to what’s growing under your ‘Braeburn’ apple tree. Any vegetation that grows within a two- to three-foot radius around the base of your tree should be removed.

Weeds, grasses, ground covers, and even beneficial plants that attract pollinators to your garden will compete with your tree for water and nutrients if they’re planted too close to it.

Plant carefully, and if you spot some weeds popping up nearby, dig them out. The chore of weeding can be greatly reduced by applying a layer of mulch.

Where to Buy

This variety is quite popular, so if you’re in Zones 4 to 9, chances are good you’ll find ‘Braeburn’ apple trees at your local nursery or garden center.

If you’re having trouble finding one locally, you can source from specialty distributors or order ‘Braeburn’ from online nurseries like Nature Hills. They offer a potted three- to five-foot tree, ready for transplanting in your garden.

Managing Pests and Disease

Like other types of apples, ‘Braeburn’ is susceptible to common diseases like fire blight, powdery mildew, rust, and scab.

All of these and more are covered in detail in our guide to identifying, preventing, and treating apple diseases.

Potential insect pests include aphids, codling moths, maggots, and spider mites. They’re all covered in our comprehensive guide to identifying and controlling apple tree pests.

This variety and a few of its close relatives are prone to Braeburn browning disorder.

It affects the fruits, changing the flesh to an unappealing shade of light to dark brown. It can be observed at the time of harvest but is most often noted post-harvest.

This cultivar seems to be genetically predisposed to the disorder.

Allowing little oxygen permeability through the cellular structure of its skin, enzymatic oxidation can cause hotspots to form inside the fruit, resulting in brown tissue.

While some say it’s triggered by climate and growing conditions and others suggest improper storage as the cause, scientists agree that factors both before and after harvest may affect the incidence and severity of the browning.

Because Braeburn browning disorder isn’t fully understood yet, studies are ongoing to help growers find better information and guidelines to prevent and treat it.

Until then, if you bite into an apple that is brown in the center, don’t panic! If it’s not too far gone, enjoy the outside. Unless it’s rotted and moldy, it won’t hurt you.

And consider sharing. On her small farm, my grandmother used to feed brown apples to her pigs. Animals love apples!

If the fruit’s beyond saving and you wouldn’t force it on your worst enemy, send it to the compost heap.

There’s no need to worry about potentially spreading disease since this physiological condition is not caused by any type of pathogen.

Harvesting and Storing

‘Braeburn’ apples are usually ready to harvest in October. The length of time to maturity can vary and will depend on your growing zone.

Read our guide to harvesting apples for an in-depth lesson.

‘Braeburn’ apples keep well after harvest in cool storage. Kept in a cold cellar, they’ll last about two to four months.

And in the crisper drawer of your refrigerator, they should remain delicious for up to one month. Our guide to storing apples dives deeper into the details if you’d like to learn more.

And remember: if they begin to go a bit soft, don’t toss them into the compost just yet!

There are plenty of creative ways to consume these beauties. Read on to learn about ways to process and enjoy them.

Recipes and Cooking Ideas

Finally, the juicy part! There’s nothing I love more than talking about food, especially when it’s a fruit as exceptional as this one.

‘Braeburn’ apples didn’t become popular just for being cute. They are delicious!

The flavor of ‘Braeburn’ is high impact with the perfect balance of sweet and tart in every crispy, crunchy bite – the ultimate snacking fruit.

Sliced in juicy chunks with a sliver of sharp cheddar or a smear of warm brie, it’s enough to satisfy any palate – from simple to sophisticated, at any age.

Pair this bite with a sauvignon blanc, chardonnay, or even a rosé for a tempting starter or highlight for a tasting party.

Find additional suggestions for planning a wine party on our sister site, Foodal.

The creamy golden flesh is aromatic with notes reminiscent of cinnamon and nutmeg, and when perfectly ripe it evokes hints of melon and pear.

It’s no wonder ‘Braeburn’ is favored for cider, use in baking, and making applesauce.

This variety is beyond versatile. It’s a good candidate for dehydrating and firm enough to keep its shape well when baked. You can even try juicing it!

Recipe ideas are endless for ‘Braeburn,’ but I’d like to share two creative versions of some well-known classics.

Easy homemade chunky applesauce offers a brilliantly simple take on an old-fashioned comfort food.

I think ‘Braeburn’ would absolutely shine here, leaning into the cinnamon and clove flavor profile like a champ. Find the recipe now on Foodal.

The next is a homage to my Swedish mother who certainly has a way with the beloved fruit of her ancestors.

Swedes sure do love their apples and they serve up desserts in all imaginable forms to prove it. I blame the Vikings for this obsession, but that’s a story for another time.

Sadly, I didn’t inherit my mom’s perfect pie crust gene, so I usually go for a crustless Swedish crumble known as smulpaj. But this fall I plan to try a fresh idea, this cinnamon apple tart cake that I also found on Foodal.

I mean, come on! Who can resist this? Part tart, part cake, with a rich and buttery cinnamon topping. Check it out!

Imagine a warm, generous slice topped with a creamy, melting scoop of real vanilla ice cream – you know, the kind where you can actually see the bits of vanilla bean? October can’t come fast enough!

If those recipes aren’t enough to convince you to grow your own ‘Braeburn’ apple trees, I don’t know what will.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Deciduous fruit tree | Flower/Foliage Color: | White/green |

| Native to: | New Zealand | Water Needs: | Low |

| Hardiness (USDA Zones): | 4-9 | Maintenance: | Low to moderate |

| Bloom Time/Season: | Spring (flowers), fall (fruit) | Tolerance: | Pollution |

| Exposure: | Full sun | Soil Type: | Loamy |

| Time to Maturity: | 2-5 years (fruiting) | Soil pH: | 6.0-7.0 |

| Spacing: | 12-15 feet | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Planting Depth: | Depth of root system (transplants); graft 1-3 inches above soil level | Attracts: | Pollinators |

| Height: | 12-15 feet | Companion Planting: | Artichokes, clover, comfrey, daffodils, dill, garlic, lemon balm, rhubarb |

| Spread: | 12-15 feet | Family: | Rosaceae |

| Chill Hours: | 700 | Genus: | Malus |

| Growth Rate: | Moderate | Species: | x domestica |

| Common Pests and Diseases: | Aphids, codling moths, maggots, spider mites; apple scab, cedar apple rust, fire blight, powdery mildew | Cultivar: | Braeburn |

Take a Chance on Braeburn

An orphan, this chance seedling started from humble beginnings. But because some insightful farmers had the wisdom to imagine its full potential, it rose to glory.

They took a chance on ‘Braeburn.’ And thank goodness they did! Now we can all have the opportunity to admire and enjoy these lovely trees and fruit.

I’ve covered everything you need to know about growing ‘Braeburn’ apples including cultivation needs, planting methods, and tips for care. I’ve even pointed you to some creative recipes and cooking ideas.

Will you take a chance on ‘Braeburn’?

If you’ve got a favorite family apple recipe to share, I’d love to try it! Drop it in the comments below.

Are you ready to jump aboard the apple train? Hop off at these Malus guides next.