Rhagoletis pomonella

Us gardeners tend not to like sharing our fruits and vegetables, especially not with wriggling maggots, and least of all when we find them in one of our favorite types of produce: apples.

Unfortunately, flies like Rhagoletis pomonella don’t ask before they lay their eggs on your fruit, so we don’t have much say in whether their larvae chow down or not.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

Or do we?

There are a variety of ways to stop these pests before they can get to your orchard fruits, and you’ll discover them in this guide.

Here’s what we’ll cover:

What You’ll Learn

What Are Apple Maggots?

Apple maggots are a major threat to Malus domestica, but these pests will also attack crabapple, hawthorn, pear, plum, cherry, and cotoneaster plants.

They are native to the eastern United States and Canada, but this species has migrated west and become a serious pest from coast to coast in North America.

In areas where the eggs were laid on the fruit, you’ll see a little dimple. As the larvae feed inside, infested fruit becomes distorted, inedible, pitted, misshapen, rotten, and discolored.

The adult flies emerge throughout the summer and are present from July to September, with populations peaking in late July and early August.

They can be confused with codling moth larvae (Cydia pomonella), and online searches for photos of R. pomonella damage will often turn up pictures of incorrectly labeled codling moth damage.

But codling moths create tunnels through the fruit, leave frass pellets behind, and their larvae have distinct head capsules and six legs – unlike the larvae of Rhagoletis pomonella.

They also grow to 20 millimeters in length, which is two times the size of apple maggots.

Apple maggots and snowberry maggots (Rhagoletis zephyria) look very similar, but snowberry maggots don’t feed on apples or pears.

Identification

The larvae are white, legless maggots, without a distinct head capsule. But they do have two dark-colored mouth hooks. When mature, they can reach six and a half to eight millimeters long.

Pupae are oval shaped, five millimeters long, and gold to brown in color.

Adults are quarter-inch-long flies that look like house flies except they have black and white markings.

Their clear wings have a black droopy VF-shaped marking, they have a white spot where their thorax reaches their abdomen, and dull red eyes. The females have four white stripes on their abdomens, while males have three.

Biology and Life Cycle

The pupae overwinter beneath the ground near host plants, and the adults start emerging in the summer, continuing to emerge throughout the season until fall.

The adults, which have a two- to four-week lifespan, may initially feed on honeydew, bird droppings, and other appetizing morsels outside of your orchard or garden, in the woods or bushy areas nearby.

After feeding for seven to 10 days they become sexually mature, mate, and the females are attracted to ripening fruit to lay their eggs in. Each female can lay up to 500 eggs.

Once hatched, the larvae feed for three to four weeks inside your apples, cherries, or pears.

Once the fruits drop, the larvae exit and pupate in the soil. This is important to be aware of for management, so keep this in mind!

Monitoring

If you wait to determine whether you have an apple maggot problem until you see damaged fruit, you’re already too late.

This insect is such a big problem, and the monitoring techniques developed and used by growers are unique and ingenious.

I often mention sticky traps in this section of pest management guides, and I usually mean those yellow sticky cards, which are available at Arbico Organics.

Those work for monitoring these flies too, but not as well as a sticky, bright red, round plastic trap.

The trap must be three inches in diameter with a bright red color to work well enough to be used as an effective monitoring tool, as well as a management tool.

So-called Ladd traps combine a yellow rectangular sticky trap with a red sphere for increased trapping capacity, and these are specifically designed to target apple maggots.

Arbico Organics carries a kit with everything you need to set up these specific traps.

A red apple coated in Tanglefoot Tangle-Trap Sticky Coating works as well but this is a waste of fruit, in my opinion.

Hang one trap per 100 fruits, and hang not only in the orchard trees themselves, but also in wild apples, hawthorn, and other wild hosts nearby. Hang the traps starting in June, and check them weekly to clean off the flies, reapply sticky material if necessary, and monitor numbers.

Organic Control Methods

In this section you’ll find a variety of control methods you can employ as part of a complete integrated pest management (IPM) strategy to attempt to control this bane of apples’ existence.

Cultural and Physical Control

Trapping the adults with the traps mentioned in the monitoring section above is one strategy that helps to reduce damage.

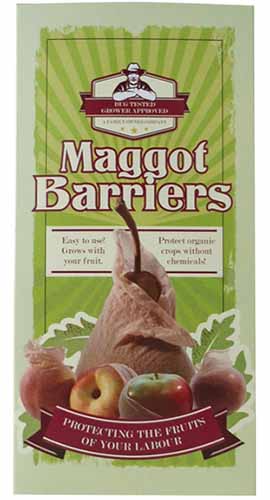

Other methods include using physical barriers.

You can use plastic bags with zip-tops to enclose fruit on your trees or staple a plastic bag around the fruit in June, leaving a small opening in the bottom for water to run out, or use the nylon bags Arbico Organics carries, which stretch with the fruit as it grows.

Technically a spray, but acting as a physical barrier, kaolin clay, available at Arbico Organics, is also used to discourage egg laying.

Traps and kaolin clay make a great control duo. Once sprayed on the plants, the light color of the clay is a visual repellant, deterring the insects from the otherwise alluring, brightly colored fruits.

The clay also acts as a physical barrier, making it difficult for the females to lay their eggs.

Kaolin clay doesn’t persist long, unfortunately, and must be reapplied after rain, and as the fruit expands.

Keeping your garden or orchard clean is also essential.

Keep an eye out for dimpled fruit, and remove and destroy them to get a jump on the larvae before the fruit fall and the larvae pupate. Pick your fruit frequently, pick up fallen fruit as soon as possible, and don’t compost infested fruit.

Biological Control

Unfortunately, biological controls are not effective against this insect.

The adults don’t have any specific significant enemies besides the odd hungry predator, and the larvae hide inside the fruit and are difficult for predatory insects and other enemies to reach.

Organic Pesticides

Using pesticides against the larvae is not helpful, but you can try applying spinosad, available as Entrust SC Naturalyte Insect Control at Arbico Organics to the foliage to suppress the adults.

Entrust SC Naturalyte Insect Control

Keep in mind that this product can be toxic to pollinators and other insects, so don’t apply it during the day if there are blooms and bee visitors present.

Chemical Pesticide Control

Because the larvae are safely hidden in the fruit, and the adults may not visit the orchard until they are ready to lay eggs, they can be hard to control with contact chemicals.

Carbaryl and phosmet, applied three to four times per season, have been used successfully against apple maggots. Keep in mind that many chemical pesticides are hazardous to beneficial insects and other organisms that could inhabit your trees.

Get Your Own Future Pie, Fly

These small flies and their irritating larvae are not easy to find and control, but luckily, we know a trick or two that can help us in the fight over our precious apples.

Traps and physical barriers might not be the best options for commercial apple growers, but for us backyard gardeners and orchardists these are manageable, effective options to try.

It’s worth at least attempting to save our future fresh snacks and pies, right?

Have you ever had issues with these common, serious pests in your garden? Let us know in the comments below how you dealt with them! And feel free to drop us a line if you have any questions.

While you’re at it, read about other pests and diseases that affect apple fruits here:

This has been an issue for five years. I began using the various traps to little avail. As the problem worsened, I cut trees back in a radical prune. This eliminated any crop for two years during which I hoped to interrupt the life cycle. It too failed. Since the life cycle begins in the ground under the trees, is it feasible to use a permeable barrier like one-way weave and sand or gravel to prevent them from exiting the soil?

Sorry to hear it, Frank! Have you tried any of the other suggestions provided in our article? I’ve heard of barriers like Orchard Sox being used to protect individual fruits from maggots, but I don’t know that a ground covering barrier will work in this case.