Malus spp.

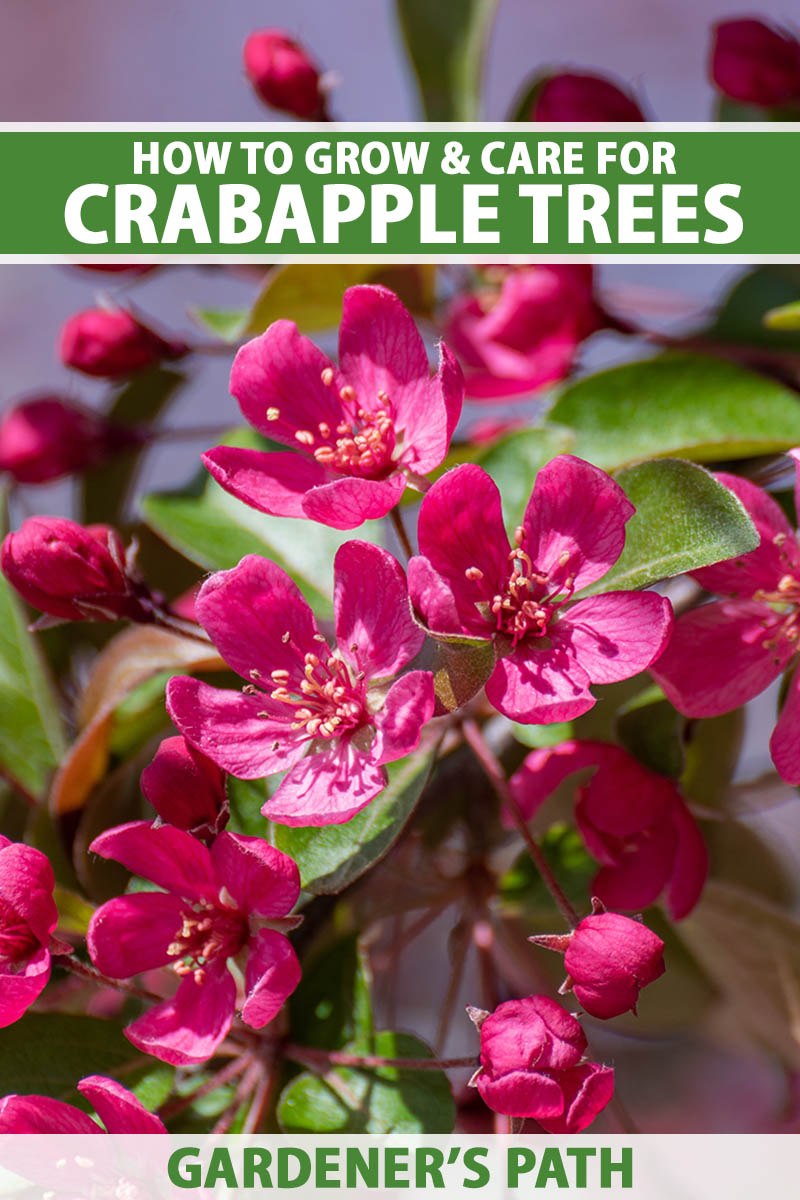

By the time mid-spring rolls around, your garden is probably a riot of flowers and colors. How could anything possibly compete with the abundance? Well, it’s easy if you’re a crabapple.

The riotous robe of colorful, fragrant crabapple blossoms seems to explode into existence all at once, making an outsized statement in a relatively petite footprint.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

We love our ornamental trees so much that some of us will go to great lengths to keep them alive.

Some years, it feels like a never-ending battle to encourage our ornamentals to thrive. Yes, I’m looking at you dogwoods, weeping birches, and silver maples.

Not crabapples, though. They’re givers, not takers.

The floral display would be enough to recommend them, but then comes the brilliant foliage and fruit in the fall, which is also edible, and it’s enough to have me running out the door to add a few more crabapples to my yard.

Are you feeling the crabapple love? Let’s dive into the nitty-gritty. Here’s what we’ll go over:

What You’ll Learn

So, there are the flowers and fruit, not to mention the pretty foliage.

But crabapple wood is also useful as firewood and for smoking meat and other foods. It’s beautifully-grained hardwood that can be used in woodworking as well.

Let’s explore all there is to know about this multitasking beauty.

Cultivation and History

Crabapples originated in the area of modern Kazakhstan and are closely related to domestic apples.

Both are in the Malus genus, but crabapples are primarily grown for the incredible floral performance that they put on every spring rather than their fruits.

But the colorful and edible fruits that the trees produce in the fall are like tiny, bitter apples. In fact, crabapples are related closely enough to the orchard apples we eat today that they can be bred with one another.

Breeders have made many crosses, most of which are called applecrab trees.

Applecrabs like ‘Almata,’ ‘Big Dog,’ ‘Candycrab,’ ‘Chestnut,’ ‘Cobbler,’ ‘Hopa,’ and ‘Pink Pearl’ are crabapple-like but these are grown for their fruit rather than solely for the flowers.

The fruits are typically larger, though they’re not as large as domestic apples.

Others, like ‘Big Lou,’ ‘Pristine,’ ‘Rajka,’ and ‘Topaz,’ are scab-resistant domestic apples with crabapple genes.

Domestic apples and crabapples will hybridize on their own in nature. And speaking of pollination, the trees are cosexual and need a partner for pollination if you want to produce fruit.

Contrary to some speculation, crabapples aren’t the sole ancestors of domesticated apples, though they certainly contributed to developing the classic fruit we know and love today.

Wild apples (M. sieversii) originated in western Asia and are considered the primary ancestor of our modern domestic apples.

Crabapples, on the other hand, naturalized across the Northern Hemisphere after being introduced from their indigenous region via the Silk Route, Roman expansion, and the European invasion of North America.

They’ve also been cultivated as ornamentals and are grown on every continent except Antarctica.

Most crabapple fruits are probably not something you’d munch on daily, but they can be pretty tasty when prepared right.

There are even some cultivars that are grown for their fruits, which are tart and delicious. The fruits are firmer and less juicy than domesticated apples, but they can have an excellent sweet-sour flavor.

The trees are also often used as rootstock for grafted apples and as pollinators for apple trees. The two look extremely similar, to the point where it can be hard for novice growers to tell them apart when they aren’t fruiting.

The leaves of both are alternate and they can be round or oval shaped, always with an angled, pointed tip. The leaves of domestic apples tend to have a hairy underside, but most crabapple foliage is smooth or only slightly hairy.

Crabapple trees tend to be smaller as well, rarely growing taller than 20 feet, but usually maxing out closer to 15. Some stay as small as six feet tall, but there are also some that may reach up to 30 feet in height. Most have a symmetrical growth habit.

The flowers have five petals – as do all undomesticated plants in the Rosaceae family – and range from pure white to bright red, with lots of pretty shades of pink in between. Some crabapple cultivars have semi-double or double blossoms with over 10 petals each.

Before the flowers even open, the buds are attractive on their own, in bold white, pink, purple, or red hues that might contrast with or match the mature flowers.

In the fall, green, red, or purple fruits under two inches in diameter will develop. Some cultivars are persistent, and the fruits won’t fall from the trees. Others will drop any fruit that hungry herbivores don’t get to first.

In the fall, the foliage changes color to yellow, orange, red, or purple.

In North America, you can find the Oregon species (M. fusca) on the West Coast, the prairie (M. ioensis) across the Midwest, the southern (M. angustifolia) in the South, and the sweet crabapple (M. coronaria) in the Midwest and East Coast states.

Native people such as the Cowichan, Gitksan, Klallam, Cherokee, Meskwaki, and Samish used crabapple trees not only as a source of food but as a gastrointestinal aid, to treat gallstones and sore throats, and as a remedy for smallpox.

When the European species (M. sylvestris) was brought to North America, Cherokee and Iroquois people used the bark to treat colds, earaches, eye problems, and bruises.

In Europe, the tree has been used for as long as we have records, both as food and medicine.

The Japanese flowering crabapple (M. floribunda) and its cultivars have some of the most striking floral displays.

Crabapple Propagation

You can buy crabapples at pretty much any nursery or home store. They’re one of those trees that’s so adaptable and reliable that people from coast to coast can grow them.

Purchasing a cultivar that is well-adapted to your region is a good way to find a plant that will be pest and disease-resistant and cold-hardy.

But shopping for the right plant isn’t your only option. You can also start crabapples from seed or by taking cuttings.

From Seed

There are lots of trees that I would never recommend growing from seed, but crabapples aren’t one of them. You can grow all kinds of interesting trees with unusual variations when you start them from seed.

Hybrids won’t grow true, but they’ll always give you something interesting in terms of blossom color and possibly fruit flavor. You can plant seeds collected from a species crabapple with a better chance of producing something close to the parent, but don’t count on it.

That’s because these trees are notorious natural hybridizers. They’re always hybridizing in nature and so their seedlings are unreliable.

To extract the seeds, wait until the crabapples are as ripe as can be. The fruit should be past the point of eating and well into the mealy stage. Just give them a squeeze, and any that feel remotely soft are probably ready.

Cut or crack open the fruit and locate the seeds. If they’re dark brown, they’re ripe.

Remove them and rinse them clean. You can either stratify them right away, or allow them to dry and then place them in an envelope or container in a cool, dark area. They’ll keep for up to a year.

When you’re ready, place the seeds in moistened potting soil in a resealable bag. Place the bag in the refrigerator to stratify the seeds for up to four months. If you see radicle growth emerging, remove the seeds from the bag and plant them.

In late winter, remove the seeds and sow one or two in individual six-inch pots. Or, you can sow them directly in prepared soil in the ground around the last predicted frost date for your area.

Gently press the seeds about a quarter-inch into the soil. Place the pots in an area that receives about six hours of direct light or add supplemental lighting.

Keep the soil moist and wait for the seeds to germinate. This can take weeks, so don’t give up if the seedlings don’t emerge right away. After the seedlings have had some time to develop, pinch out any of the smaller, weaker ones.

Once the seedlings are about six inches tall, you can transplant them from pots into their permanent spot in the early spring or mid-fall. Harden them off for a week before you do this.

To harden them off, take them outside and set them in a sunny spot for an hour. Bring them back in. The next day, add an hour before taking the pot back in.

Keep adding an hour each day for a week.

From Cuttings

Many crabapples are only cultivated via asexual propagation because they’re hybrids.

Asexual propagation is the best way to reliably reproduce the exact same characteristics of the parent plant. Cuttings clone the genetics of the parent tree.

It’s technically possible to propagate hardwood cuttings, but softwood takes better and starts growing more quickly.

Take cuttings in the early spring after new growth has started forming on a mature tree. Look for soft, new growth that is green and pliable, with about six inches of length. Make the cut at a 45-degree angle an inch below a leaf node.

Remove all but the top two leaves or leaf buds.

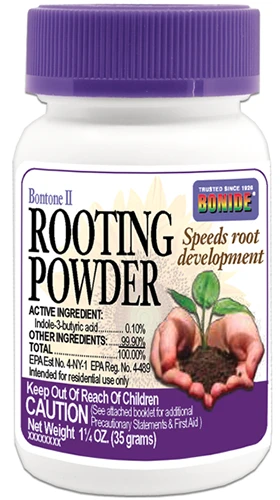

Dip the cut end in a rooting hormone like Bontone II Rooting Powder, available at Arbico Organics in 1.25-ounce containers, to help speed up rooting.

Bonide Bontone II Rooting Powder

Place the cuttings in the ground in prepared soil and water the soil well.

Depending on the expected size of the mature crabapple tree, you’ll want to space the cuttings out anywhere from five to 10 feet apart at a minimum. But you can place two cuttings right next to each other in case one doesn’t take.

If they both take, just tug out or transplant one.

Keep the soil moist but not wet, and you should see new growth within a month or two.

Transplanting

If you go the ol’ potted plant route, the job is pretty straightforward.

Dig a hole in your garden that is about twice as wide and just as deep as the container. Take that removed soil and work in lots of well-rotted compost.

While you can’t amend your soil to go as deep and wide as the entire root system will eventually grow, you can give the youngster a chance to stretch its legs and take advantage of the extra nutrients while it’s getting established.

Now, gently remove the plant from its pot and loosen up the roots a little. You can use the same method here for transplanting seedlings propagated at home. If you’re planting a bare root tree, gently spread the roots apart to detangle them.

Place it in the hole and fill in around it with that amended soil you just mixed up. You want the tree to sit as deep as it did in the original container and with the graft union a few inches above the soil.

Examine bare roots without a graft union to identify where the level of the soil was before the tree was dug up and stored as a bare root. You’ll see discoloration between where the soil was and where it ended.

Water well to both settle the soil and provide the plant with moisture. If the soil settles, add a bit more. Just don’t cover up any more of the trunk than what was covered in the pot. If you plant too deep, you increase the chances of suckering.

How to Grow Crabapples

Crabapples will grow best in full sun, but they’ll also tolerate a few hours of shade and will still produce nicely.

Full to partial shade will produce leggy foliage, and the tree might not bloom or produce fruit.

Crabapples do best in regions with cool summers, but they’re adaptable, and they’ll make do even in warmer areas. You can find cultivars that thrive in Zones 3 to 9.

They can tolerate some drought, but the soil around young trees should be kept consistently moist. Water when the top inch of soil dries out.

Once the tree is a year or two old, it can be allowed to dry out more. Annually, mature plants only need about 20 inches of rain per year, with more in the summer than in the winter.

If your trees aren’t receiving about an inch and a half of rain per month, add water. A rain gauge takes the guesswork out of the process.

If your region is prone to late frosts, avoid planting your crabapple tree near a south- or west-facing wall. This increases the temperature and might encourage your plants to bloom early, exposing them to late freezes, which will kill the floral show.

When it comes to feeding, take a pause before you grab the bag of all-purpose fertilizer and do a soil test. You might not need to feed your crabapple trees unless your soil is seriously depleted of one or more nutrients.

Your soil test will come back telling you whether you lack, say, a macronutrient like potassium. Once you know this, you can add more potassium to the soil using a potassium -heavy food. Otherwise, just let your crabapples do their thing.

Crabapples bloom in spring, and they’re divided into early to mid-season or mid- to late season types for the purpose of pollination. If you want fruits, you need to give your plant a companion, whether that’s an apple or another crabapple.

The partner plant needs to bloom at the same time so insect pollinators can transfer the pollen from one tree to another. Our guide to apple pollination (coming soon!) has all the details.

Growing Tips

- Plant in full sun to part sun. Shadier conditions result in leggy growth or a lack of fruit and flowers.

- Trees need approximately 20 inches of rain per year with less in the winter and more during the growing season.

- Most trees won’t need fertilizing unless your soil is depleted.

Pruning and Maintenance

Crabapples will send out lots and lots of suckers, particularly if you plant them too deep.

Some modern cultivars are less prone to suckering, so if that’s important to you, look for those described as such. Grafted types are more prone to suckering.

Cut out those suckers, or you’ll end up with a crowded patch of new trees.

While crabapples are pretty tough, with strong, hard wood, they’re not immune to breakage. They’re just less likely to break in ice and snow than many other plants. If branches do break, prune off any broken ones below the site of the damage.

Prune out any crossing or diseased limbs, as well as any water sprouts and branches that are low enough to impede travel or touch the ground. You can also take out some of the interior branches to ensure a nice open canopy.

Pruning can be done from the winter through spring, but don’t prune after May rolls around, or you run the risk of trimming off the next year’s developing flower buds.

Crabapple Cultivars to Select

When I mentioned that crabapples are easy to grow, I forgot about the hardest part: narrowing your choice down to just one!

On second thought, why stop at one? Here’s just a tiny taste of what’s out there:

Lollipop

Looking for something sweet and petite?

Lollipop® (aka ‘Loizam’) grows to just 10 feet tall but is absolutely dripping with pretty pink buds followed by a burst of white blossoms on a rounded, symmetrical canopy.

The medium green foliage turns bright yellow in the fall and contrasts beautifully with the bold red fruit. Even better, those itty-bitty crabapples stay on the tree throughout the winter.

Make the wildlife in your area as happy as can be by bringing one home to your garden in Zones 4 to 8 from Fast Growing Trees.

Prairifire

‘Prairifire’ is a stunning little hybrid with fragrant, purplish-pink double blossoms in such large masses that the tree almost resembles a redbud.

It grows up to 20 feet tall and equally wide with a rounded growth habit.

The fruit is dark red but it’s not flavorful. This is definitely more of a looker than a fruit tree, and the foliage is lovely, too.

It emerges reddish-purple before maturing to medium green, contrasting beautifully with the reddish bark on young growth.

Nature Hills Nursery carries this outstanding option in four- to five-foot bare roots for growing in Zones 4 to 8.

Robinson

Massive soft pink flowers and bold red persistent fruit recommend this lovely tree. It has an oval growth habit, spreading a bit wider than its ultimate 20-foot height.

It’s also disease-resistant, and the red fruits pop up starting in September to the delight of onlookers and critters alike.

If you live in Zones 4 to 8, you can bring the ever-popular ‘Robinson’ home from Fast Growing Trees.

Managing Pests and Disease

One of the things that makes crabapples easier to grow than their domesticated cousins is that they’re much tougher.

While apples may seem to struggle with some sort of issue every year, you’ll find that crabbies are typically healthy – unless they’re stressed, for some reason.

Stress comes from drought, standing water, poor drainage, or a lack of nutrients.

And herbivores pose another challenge.

Herbivores

Birds, squirrels, and other herbivores will eat the fruits off of the trees.

This is especially true in the winter when there isn’t much else to eat. Don’t worry about it though, there’s always plenty to go around.

There is really only one herbivore to worry about, and that’s our friend the deer.

Some gardeners call apple and crabapple leaves “deer candy” because they seem to like nothing better, and they will also eat the fruits.

Browsing can be a serious threat to young trees, so provide them with some protection.

Once they’re a bit older, they should be able to withstand all but the most aggressive deer dining, depending on the size of the tree.

If you don’t already have a deer-control strategy, our article can provide you with some tips.

Insects

As we mentioned, only stressed trees will usually suffer from a serious pest infestation.

Aphids and spider mites will probably visit your tree now and then, but they rarely become a serious threat. Mostly, they’re just a nice snack for the beneficial insects in your garden.

Aphids

There are two common aphids you’ll find on Malus species, and these are green apple (Aphis pomi) and spirea aphids (A. spiraecola). These are usually green.

When they’re present, they use their piercing-sucking mouthparts to feed on the sap of the tree, and they particularly adore the young shoots and flower buds.

It’s common to see some yellow stippling on the foliage, if you notice anything at all. You might also see a funky black coating called sooty mold. This is a fungus that’s attracted to the sticky honeydew that aphids excrete.

Our guide has lots of tips for controlling aphids. If you are going to eat the fruits, choose a control method that doesn’t involve insecticides unless they are labeled for safe use on food crops.

A strong spray of water is usually enough to get the situation under control.

Borers

Borers only attack stressed trees. They look for openings caused by damage or for trees that are drought-stressed.

When the flatheaded apple tree borer (Chrysobothris femorata) finds a subject, the adult beetles lay eggs that hatch to reveal yellow-white larvae that bore through the trunk and branches.

On the outside, you might see frass, a waste product that looks like sawdust, coming out of holes. You might also see cracks in the bark that may or may not ooze sap.

As the larvae make their tunnels, they might become so extensive that it completely cuts off or girdles branches. The bark may turn dark brown, too.

A somewhat healthy tree will produce sap wherever it is injured by the larvae, and this sap will drown them to death. But weak trees won’t be able to do that.

The only control in that case is to use an insecticide regularly to kill the adults before they can lay their eggs.

Monterey Take Down Garden Spray

Arbico Organics carries Monterey Take Down Garden Spray, a pyrethrin product, in 32-ounce ready-to-use spray bottles or pints of concentrate.

This type of spray can be highly effective. Just keep in mind that it might also harm beneficial insects, which leaves your trees more exposed to pests like aphids and spider mites.

Spider Mites

Two-spotted (Tetranychus urticae) and European red mites (Panonychus ulmi) feed on all parts of the tree, but they prefer young growth.

When present, you’ll see stippling on the leaves and the fine webbing they leave behind. A serious case might cause the small twigs on the tree to turn red.

Treatment is usually as simple as applying a strong spray of water, or you can use one of the many effective options in our guide to managing spider mite infestations.

Disease

Technically, any disease that can infect an apple can infect a crabapple.

But in practice, you’ll usually only see apple scab, cedar apple rust, fire blight, and powdery mildew, and those appear only in stressed trees.

Read our guide to apple diseases for more information on these.

Excessive feeding, overwatering, or alkaline soil can cause chlorosis. This physiological disorder results in yellow leaves with green veins.

Best Uses of Crabapple Trees

Anywhere that you need a small tree that can offer up color in the spring and fall, and sometimes through the winter as well, crabapples can do it.

Their roots aren’t invasive, so you can plant them near your home or patio, or in a small garden. They’re also ideal if you need something to pollinate your apple tree.

Choose a cultivar with persistent fruit if you don’t want to deal with the mess of fallen fruits.

Some cultivars have extremely brilliant foliage, or they might have colorful reddish bark that appears on young branches. Others might have mottled bark that looks beautiful even when the plant is bare.

Tolerant of clay soil, pollution, and drought, along with its smaller stature, the crabapple is also a good option for parking strips.

The fruits can make a killer jam, wine, liqueur, or syrup. Bake them into pies and tarts, or use them in savory recipes. Pickled crabapples are delicious on proteins like lamb and chicken, or you can bake them into bread or cookies.

Crabapples naturally have a lot of pectin and malic and tartaric acid, which makes them obvious candidates for homemade jellies.

If smoking meat is your thing, crabapple wood adds an exceptional flavor.

The fruits generally ripen in fall when they turn from green to their mature color, which is typically a red shade.

Some persist throughout the winter and some fall from the tree in the fall – if the animals don’t get to them first. Hand pick them when they reach maturity.

By the way, don’t panic if your tree produces tons of fruit or blossoms one year and less or hardly any at all the next year. Many crabapples are alternate bearing.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Deciduous fruit tree | Flower/Foliage Color: | White, cream, pink, purple/green (red, yellow, orange in fall) |

| Native to: | Western Asia | Maintenance: | Low |

| Hardiness (USDA Zones): | 3-9 | Tolerance: | Clay soil, drought, pollution |

| Bloom Time/Season: | Flowers in spring, fruit in fall | Soil Type: | Moderately sandy, loamy, moderately clayey |

| Exposure: | Full to partial sun | Soil pH: | 5.5-6.5 |

| Time to Maturity: | Up to 10 years | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Spacing: | 5-10 feet depending on type | Attracts: | Pollinators |

| Planting Depth: | 14 inch (seeds), same depth as container (transplants) | Companion Planting: | Apples, dogwoods, hostas, plums, tree peonies |

| Height: | Up to 30 feet | Avoid Planting With: | Cedars |

| Spread: | Up to 30 feet | Uses: | Patio, specimen, pollinator, small gardens |

| Growth Rate: | Moderate | Family: | Rosaceae |

| Water Needs: | Moderate | Genus: | Malus |

| Common Pests and Diseases: | Deer, aphids, borers, spider mites; Apple scab, cedar-apple rust, fire blight, powdery mildew | Species: | Angustifolia, coronaria, floribunda, fusca, ioensis, sylvestris |

Pretty with a Purpose

I know I went on and on about how great crabapples are in this guide.

They bloom in a cloud of fragrance and color, offer up edible fruits, change their colors in the fall, and they make one heck of a smoking wood for cooking.

But there’s one last thing to mention: pollinators love them.

Even if you don’t have an apple to pollinate, you’ll draw all the happy bees, butterflies, and such with your blooming crabapple tree. Then, they’ll move on to the other plants in your garden. Everyone wins.

How do you plan to use your crabapple? Looking for something to dress up a patio? Planning to make the world’s best jam from the fruits? Share your ideas – and your recipes – in the comments.

Next up, I know you aren’t done with your garden design. Do you need a few more multipurpose landscape trees? Check these out: