Epilachna varivestis

As an established soft-hearted person and gardener, I strive to love all creatures great and small. But Mexican bean beetles, Epilachna varivestis, put me to the test.

These bugs and their larvae plague different types of bean plants in the home garden.

I grow legumes in East Tennessee, where mid-to-late summer is sometimes described as “hell’s doorstep.” Mexican bean beetles do their worst damage in just that type of weather.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

Often, I’ll have a crop of ‘Christmas’ limas or ‘Cherokee Wax’ beans coming along nicely when they appear and start decimating leaves, which can downgrade the yields to adequate rather than abundant, or even cause plants to die.

It just seems mean, that’s all.

On the plus side, Mexican bean beetles can defoliate as much as 20 percent of a plant’s leaves without doing any substantial damage to the crop, and they only rarely consume enough blooms or pods to make a difference to the harvest.

Also, if you’re alert, you can prevent these pretty-but-harmful bugs from attacking – or from gaining a stronghold once they appear.

In this guide, we’ll look at our foe, with plenty of tips for identifying, controlling, and preventing these beneficial ladybug lookalikes. Here’s what I’ll cover:

What You’ll Learn

What Are Mexican Bean Beetles?

E. varivestis are a variety of ladybug, and they’ll eat bean plants during their adult and larval phases.

Don’t let their common moniker trick you – they’re also known to attack other legumes like alfalfa and clover, and will nosh on foliage from eggplants, okra, and squash, too.

Since the adults are able to fly in search of food, it’s extra important to keep an eye out for the larvae on any potential hosts in the home vegetable garden.

You’ll know they’ve infested your garden when you spot their handiwork: patches of gnawed-looking leaves, followed by skeletonized, lacy foliage that has dried from the underside up.

Mexican Bean Beetle Biology and Life Cycle

The adult beetles will overwinter in soil or plant debris. As soon as the weather warms up in spring, they emerge from the ground and start eating leaves.

It’s also possible that all or some of the adults that spent the winter in or near your garden will not emerge until a few weeks later–in early to mid-June.

Whenever they make their appearance, the adults will feed for a week or two and then lay vast quantities of eggs on the undersides of leaves.

The eggs stand vertically, in clusters of 40 or 50, and can hatch within a week in warm weather.

After the larvae hatch out, these squishy dudes congregate to pupate, usually on the undersides of leaves.

They’re the most destructive at this stage, able to skeletonize plants in a few days, and sometimes they feed on blossoms or young pods, too.

Identification: How to Tell Mexican Bean Beetles and Ladybugs Apart

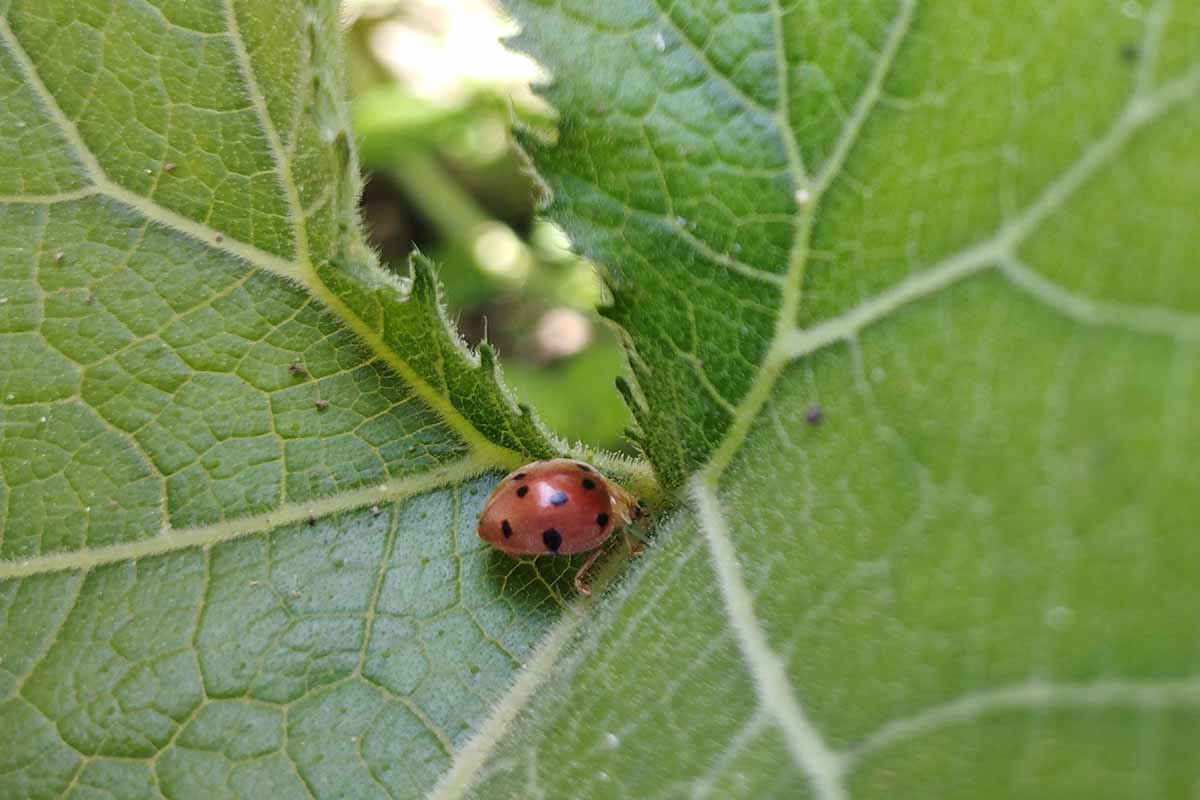

One reason gardeners sometimes allow Mexican bean beetles to proliferate in their veggie patch is that they look so much like their ladybug relatives.

E. varivestis adults are about a quarter of an inch long, orange-red with 16 black spots. They get darker as they age and are a coppery color at maturity.

Intriguingly, the larvae are robust and can be closer to a half-inch long – twice the length of the adults.

They start out light yellow after hatching and are covered with light yellow spines that become more noticeable, with darker tips, when the larva is a few hours old.

The other bug is also known as the ladybug in the US, or the ladybird beetle elsewhere.

The most common are convergent ladybugs, Hippodamia convergens, who are rock-stars in the veggie garden since they consume any number of soft-bodies insect pests, including aphids, scale, and thrips.

Gardeners may leave their destructive lookalikes alone, thinking they’re protecting precious ladybugs.

To avoid this mistake, it’s important to determine which beetle is flying about your garden.

Check to see if they have heads the same color as their bodies. If they do, that’s a Mexican bean beetle, and it’s here to eat leaves, not aphids! Harmless ladybugs, on the other hand, have all-black heads.

The larvae are another tipoff. While both types of insects lay yellow eggs, beneficial ladybug larvae are black and yellow, not the robust yellow, spiny blobs indicative of Mexican bean beetle larvae.

Once you’re sure you’re dealing with the these foes, not the aphid eaters, consider different ways to control their populations.

We’ll start with the simplest cultural and physical controls, and let’s hope that’s all you’ll need.

Organic Control Methods of Mexican Bean Beetles

Knowing Mexican bean beetles can do substantial damage, it’s tempting to proceed directly to a harsh chemical for relief.

But it’s wiser to try the organic control methods first, not only because they are less harmful to beneficial insects, but because many of the steps you take to prevent or treat E. varivestis organically can also yield healthier plants and a bigger harvest.

Cultural

Consider planting a small number of snap beans as a trap crop once the soil is warm enough to sow in late spring.

Any adults that overwintered the previous fall near the new planting will be drawn to the trap crop to feed and lay their eggs.

Then, before you plant your “real” crop, you’ll uproot the trap crop of infested plants and toss them in the trash in sealed bags. You can destroy an entire generation this way.

Physical

Physical barriers can work to keep the eggs, and thus the larvae, off of bush bean plants, though they’re not effective for pole varieties.

Use a row cover atop entire rows of bush beans, setting it out when the plants are a couple of inches tall.

If you’ve had problems before and want to fully exclude the bugs, consider anchoring the row cover with clips, weights, or a bit of soil at the bottom.

Make sure the cloth covers the foliage but doesn’t rest directly on the leaves, or it can cause them to develop rust. You won’t need to remove the row cover until you’re ready to harvest, since these plants are self-pollinating.

Once plants are established in the garden, be vigilant about inspecting them to detect Mexican bean beetles in different life stages.

Look on the underside of leaves for the eggs, which you can wipe off with a water-moistened paper towel that you then throw away.

Or, cut the egg-laden leaf off the plant and trash it in a plastic bag. If you remove only a leaf or two from each plant, it should grow on without any trouble.

If the larvae are allowed to emerge, you can hand-pick and destroy them. It’s only a little icky, and doing so keeps harmful sprays away from your beans and other vegetables.

They’re a bit faster than the larvae and they can fly, but you can also pick adults off the plants. Drop them in a plastic zipper bag or a lidded container with a few tablespoons of vinegar for disposal.

Biological

Consider introducing beneficial insects such as green lacewings or the aforementioned ladybugs, and integrated pest management to keep the beetles at bay via natural predators.

Learn more about the process in our guide.

Organic Pesticides

Widespread infestations may require the use of organic insecticides like neem oil, but use them only as a last resort.

Any time you apply pesticides you risk harming beneficial insects, particularly bees and other pollinators, as well as your target pest.

Some of the more harsh options can also burn the plants.

Chemical Pesticides

You’ll notice the plants can survive and keep producing pods even after about a fifth of the foliage has been skeletonized, so it’s usually easiest to trash the most affected plants and try again next year versus getting into extensive insecticide application.

Mexican Bean Beetle Prevention Tips

Happily, most of the steps you can take to prevent these specific insect pests from infesting your plants will benefit your crop and increase yields, too. And they’ll also help to keep other bugs and diseases at bay.

First, grow healthy plants able to withstand defoliating from Mexican bean beetles. Ample water, well-draining soil, full sun, mulch, and a weed-free garden plot will aid the cause.

Learn more about growing healthy home garden crops in our guides to pole beans, bush beans, and limas.

Also, prevent the pests from overwintering in soil or plant debris and emerging the following season by rotating crops on a three-year basis and composting or destroying dead plants at season’s end. Learn more about what can be composted in our guide.

If Mexican bean beetles are a problem in your area or in your particular garden, be sure to sow fast-growing snap varieties in the hope of harvesting before mid- to late summer, when E. varivestis does the most damage.

One good option is ‘Contender,’ a hybrid bush type that produces an abundance of five- to six-inch, heavy pods and matures in about 55 days.

It does well in the moderate temperatures of late spring and sets pods in hot weather too.

Find 200- and 800-seed packets of ‘Contender’ available from Burpee.

You may also want to grow the types of beans that are the least appealing to this insect pest.

Studies have shown that Mexican bean beetles prefer snaps to limas, mung beans, cowpeas, and soybeans, and they go after wax beans – the ones that produce yellow pods – more than they do green snaps.

Late in the season, soybeans are preferred.

If you aim to produce a dried crop for storage, consider cowpeas, which are not a favorite (though the beetles will eat these leaves as well, in a pinch).

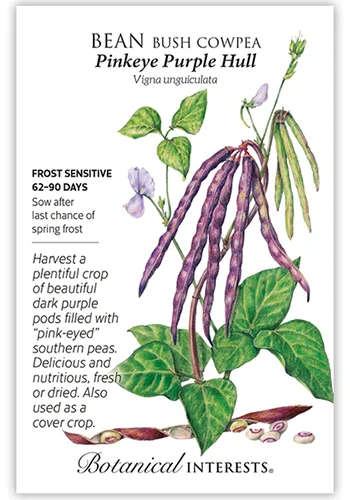

‘Pinkeye Purple Hull’ bush cowpeas are pretty, resist drought, and grow on compact bushes that reach just two feet tall and start to produce after about 62 days.

This variety is available in 100-seed packets from Botanical Interests.

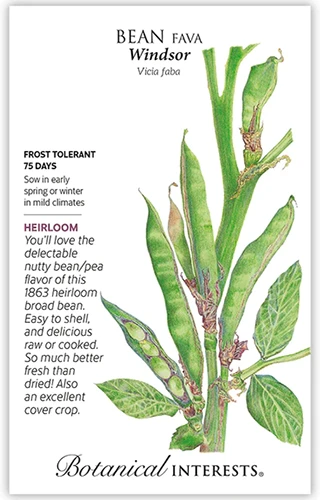

Favas have dual advantages in this situation. They aren’t a favorite of E. varivestis, and they’re also a cool-season crop that grows in temperatures as low as 40°F.

They stop producing once temperatures reach 75°F, which is coincidentally right about the time when Mexican bean beetles start doing their worst.

‘Windsor’ fava is available in 18-seed packets are from Botanical Interests.

Learn more about growing and harvesting favas in our guide.

Uncool Bean Beetles

They do have a similar whimsical polka dot pattern, but once you know how Mexican bean beetles ravage legumes, you’ll never spot one and think “How cute, a ladybug!” again.

Do you have any tips for combating these pests? Kindly add your input or questions to the comment section below.

And for more helpful info on growing easy-care legumes in your garden, have a read of these bean guides next: