When you think about xerophytic or drought-adapted plants, you might immediately picture a saguaro cactus and other similar species, and you’re not wrong – but there are so many more, and a lot of them are colorful flowers, useful herbs, and beautiful trees.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

Even if you don’t live in an arid environment, you can still choose species that naturally conserve water, and do your part to protect precious and dwindling resources.

There’s no need to sacrifice aesthetics with so many choices available – I bet you’ll be pleasantly surprised!

Many of the different species included on our list can adapt to a range of climates, so you’re sure to find many new favorites for your landscape or garden.

Here’s a sneak peak of the more than two dozen options we’ll cover in our roundup, up ahead:

27 of the Best Xerophytes to Grow at Home

If you’re not sure where to start with planning a water-wise garden or landscape for your particular space, be sure to read our guide to designing with xerophytes.

There are so many potential species to choose from that we’d be here for ages if we listed all of them.

Instead, here are some of the best and most lovely plants that are known to make great additions to a xerophytic garden or landscape according to your hardiness zone.

1. American Agave

If you’ve read our guide to growing and caring for agave, then you know what an amazing genus it is. Almost all agaves make perfect choices for the xerophytic garden, as they store water for long periods, and enjoy hot temperatures and lots of sunlight.

American agave, or Agave americana, makes a fantastic, large focal point that can reach heights of around 10 feet at maturity.

Once in its lifetime, it produces a flowering stalk that resembles a giant asparagus – which makes sense since these plants are part of the Asparagaceae family. This stalk sometimes reaches more than 20 feet tall!

Once blooming ends, the agave begins to die off, but don’t worry – they don’t usually bloom until they’re between 10 and 80 years of age.

This species exhibits marginal teeth and leaves tipped with sharp spikes, so it’s best set apart from high-traffic areas.

Add A. americana in places where the substrate is sandy and well-drained, and where temperatures remain higher than about 50°F consistently, such as in USDA Hardiness Zones 7 to 11.

A blue American agave in a three-gallon pot is available from FastGrowingTrees.com.

If this species is too large for your space, or you need one that is more cold hardy, there are more than 200 other species to choose from.

2. Blackfoot Daisy

Cold-hardy xerophytes are a bit more difficult to track down, but Melampodium leucanthum, or blackfoot daisy, is a perfect choice in Zones 5 to 11.

Compact, mound-forming plants have small leaves with a gray-green tint and small, white, daisy-like blooms with yellow centers. This herbaceous perennial reaches about six to 12 inches tall at maturity, with an 18- to 24-inch spread.

Native wildflowers such as these make for easy caretaking, with only a drink of water required occasionally throughout the summer months to keep them blooming, and some supplemental water here and there through the year.

Dry, sandy soil is ideal for this species, which typically enjoys full sun for up to 12 hours per day.

We happen to have a comprehensive growing guide on the blackfoot daisy, so take a look if you’re interested in finding more information.

If you’re adding this specimen to your planting list, check with a garden center near you.

3. Blue Chalksticks

One option that makes an attractive, spreading ground cover is blue chalksticks (Senecio serpens). Just as the name suggests, this succulent forms short, chalky blue, fleshy leaves that stand mostly upright, but only reach about 12 inches in height.

With a two- to three-foot spread, it’s a perfect choice for covering open ground without requiring tons of water. It’s also an excellent mass planting specimen, which really pops when combined with other species in tones of yellow, coral, or orange.

In the summer, small white blooms develop. They’re not large or showy, and some gardeners choose to nip them off to keep things orderly.

This species is best suited for growing in USDA Hardiness Zones 10 to 11, and it is not cold tolerant.

Blue chalksticks are available in a one-gallon grower’s pot from Altman Plants via Home Depot.

4. Bougainvillea

One of the best features of bougainvillea (Bougainvillea spp.) is its versatility. It can be shaped in so many ways – create a tree or shrub, trim it to fit neatly on a trellis, or let the vines cascade freely over a rocky wall.

From a distance, it appears that these vining perennials are loaded, even overflowing, with luscious, brightly colored blooms.

In fact, it does flower, but the true flowers are tiny, white, and barely visible. The colorful clusters in magenta, white, orange, and purple are actually bracts.

Bracts are leaves that are designed to protect the small blooms while also attracting pollinators – and attract, they do. Bougainvillea is known for bringing butterflies, bees, hummingbirds, and moths to the garden.

In USDA Hardiness Zones 9 to 11, you can simply plant these beauties in the ground against a sturdy support and let them grow, or keep them pruned. Learn all about growing bougainvillea in our comprehensive guide.

Note that these vines, which can sometimes grow to more than 20 feet in length in ideal conditions, have thorns arranged between their leaves. It might be best to keep them trained to an area away from foot traffic.

‘Sundown Orange’ is a gorgeous orange cultivar that is available from Fast Growing Trees.

5. Calendula

Need some color to enliven a dull bed? Maybe a pop to add around the mailbox or to draw the eye for some curb appeal? Or something that allows you to go all out, broadcasting seeds over an expanse of ground for a cheerful mass planting?

Look no further than calendula (Calendula spp.). Sometimes referred to as a marigold or pot marigold when it’s not a true marigold at all, both marigolds and calendula are members of the Asteraceae family, but they belong to two different genera.

These plants produce little, one- to two-inch-wide spots of sunshine that can be planted almost anywhere – full sun, partial shade, well-drained sandy loam or loamy soil, and in a huge range of climates from Zone 2 to 11!

Usually started from seed, they quickly sprout and grow to their full 18- to 24-inch height within six to eight weeks. They make beautiful cut flowers, have medicinal properties, and feed our pollinator friends. They do it all!

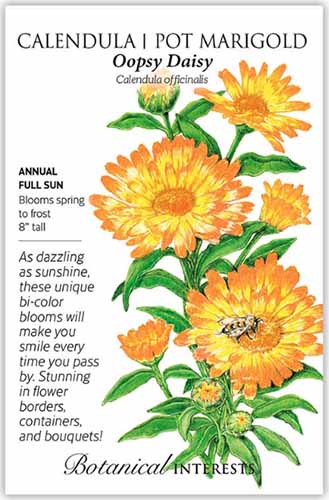

Grab a packet of 700 seeds for the compact ‘Oopsy Daisy’ cultivar, with blooms that sport yellow centers and orange outer petals, from Botanical Interests.

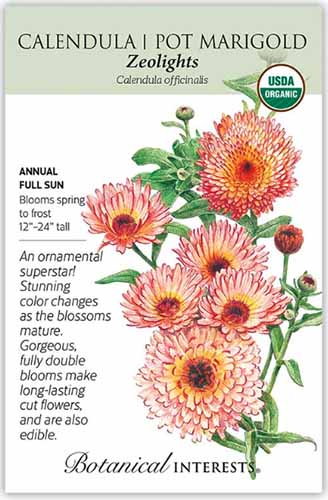

Or, consider ‘Zeolights,’ a cultivar with blooms of pink dotted with bright yellow centers – also in a pack of 700 seeds from Botanical Interests.

For more growing information, we have several guides, including how to grow, winter care, and pests of calendula.

6. California Poppy

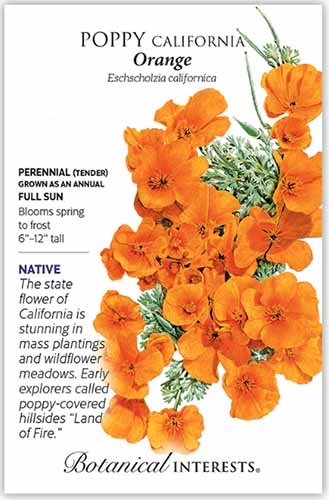

Also referred to as golden poppy, California poppies (Eschscholzia californica) are native to California and other areas along the West Coast of the United States.

They prefer sandy, well-drained soil, but can often be found growing wild in bluffs and crevices, on plateaus, and even in areas with more fertile soil.

Even though poppies are adaptable to many growing conditions, they’re considered ephemeral xerophytes due to a special adaptive feature of their seeds.

Native to regions where drought conditions are common, sometimes for a long period of time, their seeds remain viable until an adequate amount of rainfall is received, and then they suddenly burst into life.

The flowers then bud, bloom, and die within a few weeks, spreading their seeds for the next generation of plants.

Flowers can reach up to 12 inches in height, with blooms three to four inches in width. The flowers are typically orange or deep yellow, but cultivars such as ‘Alba’ and ‘White Linen’ have been developed to have white- or cream-colored petals instead.

In USDA Hardiness Zones 8 to 10, these poppies grow as short-lived perennials, but further north, they’re grown as annuals – although, they tend to prolifically reseed.

Add them to sandy beds with good drainage in full sun, and enjoy their bright, cheerful color between April and June.

Seeds are available in 750-milligram, two-gram, and 10-gram packets from Botanical Interests.

Learn more about California poppies in our guide.

7. Cosmos

I bet you’ve already heard of cosmos (Cosmos ssp.). Maybe you’ve seen them available in seed packets at your local garden store – but I bet you never knew that cosmos are xerophytes.

I’ve read dozens of articles on these flowers, but never once did I see that fact mentioned!

It’s pretty important, though, for gardeners who are desperate for beautiful blooms and candy colors, but who have trouble finding those things in plants suitable for their growing conditions.

Most species and cultivars are annuals, but in some regions, or under certain circumstances, some may survive from year to year as perennials.

For example, chocolate cosmos (C. atrosanguineus) are considered tender perennials – that is, they won’t survive harsh winters, but can be brought indoors or protected north of Zone 7.

Sulfur cosmos (C. sulphureus) are another species that will power through low temperatures to return perennially. But, even if most species are annuals, they are prolific reseeders that will often sprout again in the next growing season anyway.

Add them to your garden in beds, create mass plantings, or grow whole fields full of their big, beautiful blooms. All they need is full sun, well drained soil, and a little water now and then in Zones 2 to 11.

Grab some sunny sulfur cosmos from Eden Brothers in packages ranging from one ounce to 10 pounds.

All of the information you need to grow and care for cosmos is right here in our guide. And, for more inspiration, check out our roundup of recommended varieties!

8. Creeping Sedum

A succulent ground cover is indispensable when it supplies color, texture, and a layer that can slow evaporation from the substrate below. Creeping sedum, or stonecrop, (Sedum spp.) is one such succulent.

There are hundreds of different types of sedum, and a large portion of that number are creeping varieties – that is, low-lying types with fleshy stems and small leaves that can spread throughout an area.

Most can spread between one and several feet, but generally achieve no more than five to six inches in height.

One huge benefit with plants from this genus is the range of growing conditions they can tolerate.

You’ll find varieties suited for growing in any Hardiness Zone between 3 and 11 in the US, and chances are there will be several color choices available to you, too.

They’re beautiful, easy-care additions to a rock garden or gravel bed, placed in between stones in a wall or edging a pathway, or filling space between other larger specimens.

Harsh sun and dry, lean soil are preferred – excess water and highly nutritive soil can actually lead to poor health.

Add a pop or a swath of color with cultivars such as ‘Creeping Blue,’ ‘Purple Emperor,’ or ‘Golden.’

Pick up a four-inch grower’s pot of S. dasyphyllum ‘Major Coriscan,’ a soft blue cultivar with a compact habit, from the DH7 Enterprise store via Amazon.

Another great choice is this ‘Tokyo Sun,’ available in two-inch or four-inch pots, also from the DH7 Enterprise store via Amazon.

Learn more about growing sedum in our guide.

9. Euphorbia Tree

Small understory trees and shrubs to add to the xerophytic garden can be challenging to find, but spurge, also known as the euphorbia tree (Euphorbia lambii) makes a striking focal point and worthy addition.

However, it should be noted that this species is toxic – coming into contact with the milky sap may irritate skin and accidentally ingesting any part of the plant can lead to serious medical consequences, so don’t place it where people or pets will be tempted.

Short trunks that branch into a wide canopy of lance-shaped leaves fit nicely into smaller spaces, and as this species only achieves about six feet in height and width, it’s great for corners and framing beds where a little shade is needed.

Leaves form pom-poms of green with yellow-green clusters of bracts, or leaves that resemble flower petals, capping each one in the spring and summer.

Sandy substrate amended with compost is perfect for this species, which grows quickly and can self-propagate through seed dispersion. Grow this attention-getter in Zones 9 to 11 for easy caretaking, color, and interest.

Or, if a shrub-type is more suited for the site you have in mind, see our guide to E. biglandulosa, the gopher plant.

10. Ice Plant

In cooler regions, the list of succulents available for outdoor planting is rather brief. That’s when Cooper’s hardy ice plant (Delosperma cooperi) comes in to save the day.

Unlike blue chalksticks, which make a lovely ground cover but produce small, insignificant blooms, ice plant really explodes with color.

The daisy-like flowers come in more than a dozen different shades, such as yellow, orange, red, purple, magenta, and bicolors.

This species makes for a useful source of forage in cooler zones as well, as its blossoms begin to open in late spring or summer and continue to bloom through fall in most regions.

Hardiness Zones 4 to 9 are suitable for growing various Delosperma species, but north of Zone 7, they’re typically grown as annuals or potted to move to shelter through the winter.

Succulent ice plants can survive drought, but struggle or die in frost and snow.

As a low-growing species, ice plant remains under about eight inches in height at maturity, but spreads to form lush, creeping mats of color that can reach more than 24 inches wide. Full sun or partial shade and sandy or rocky soil will keep them thriving.

You can find ‘Jewel of the Desert Ruby’ ice plants available from Hirt’s Gardens via Walmart.

11. Kalanchoe

Since kalanchoes (Kalanchoe spp.) are succulents, they exhibit the thick, fleshy leaves and stems that are expected.

But, unlike some succulents that never or rarely produce blooms, kalanchoes almost always do when grown outdoors in suitable conditions. As monocarpic succulents, they’ll do this just once.

Members of this genus are diverse, and you’ll find a wide range of forms available – some are compact, reaching no more than three feet in height at maturity, but others, like K. beharensis, can reach up to 20 feet tall!

It’s really up to you which type suits your particular needs and preferences.

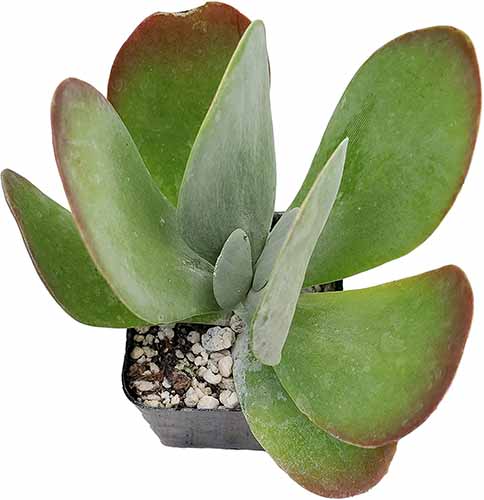

Certain species, like K. luciae, also known as paddle plant or flapjacks, are often marketed as houseplants, and it’s true that they grow well indoors.

Outdoors in certain regions encompassing Zones 9 to 11, they lend gorgeous pops of drought-resistant color and important forage for pollinators as well.

Paddle plant typically exhibits large, five- to six-inch, flat leaves of green with bright red margins.

‘Oricula’ and ‘Fantastic,’ cultivars of this species, both exhibit leaves in tones of red, yellow, and green. For all varieties, these are arranged in rosettes that resemble a stack of pancakes – hence the name – and produce long racemes of yellow to orange blooms.

In the landscape, kalanchoes only need watering once every couple of weeks in the absence of rain, a well-drained substrate, and full sun.

They’ll send out offshoots to continually self-propagate, but after they bloom, the parent plant will die off. Be prepared to remove dead specimens as they wither.

Two-and-a-half-inch specimens are available from Fat Plants San Diego via Walmart.

Learn how to grow kalanchoe in our guide.

12. King Sago

Sometimes referred to simply as sago palm or Japanese sago, the king sago (Cycas revoluta) isn’t a true palm! This living fossil has been around since dinosaurs roamed the Earth.

Because of its appearance, it’s commonly grouped among other species of palm trees mistakenly, but in fact, the king sago is a cycad.

It’s extremely slow-growing and can sometimes take more than 50 years to reach its mature height of about 15 feet – but in xerophytic gardens, it’ll normally remain more compact at five to eight feet in height.

One of the key differences between cycads and some types of palms is reduced water consumption in the former, so a king sago can be grown in arid regions more easily. However, in harsh sunlight, they prefer some shade.

Some palm trees such as the date palm (Phoenix dactylifera), which is best known for the date fruits it produces, are also xerophytic and can withstand extended drought conditions.

King sagos are beautiful specimens. Long, palm-like leaves sprout from the top of a roughly textured trunk and these can sometimes reach five to seven feet in length.

Male plants produce a reproductive structure that resembles a yellow cone up to two feet in length, while females produce a fuzzy globe full of orange seeds.

Give the king sago a place in your garden if you’re located in Zones 8 to 11. It’s super hardy down to about 15°F and can sometimes withstand temperatures even lower.

This species can also hold up to temperatures well over 100°F, but it may need some shade.

Note that this specimen is known to contain toxins, so keep people and pets away if you’re concerned about accidental ingestion.

Pick up a sago palm in a three-gallon container from FastGrowingTrees.com.

You can learn more about sago palms in our guide.

13. Moss Rose

These easily recognizable, ferny semi-succulents with brightly colored blooms often go by another name – portulaca (Portulaca spp.). Native to Brazil, Argentina, and other semi-arid regions, it makes sense that they’re xerophytic.

While they’re not quite as conservative in their water consumption as some of the other species we’ve covered, they do store water in their leaves and stems, and enjoy full sun, heat, and well-drained soil.

Common purslane (P. oleracea) is a close relative, which you might be fighting to keep off of your driveway or sidewalk – but don’t fight too hard, because it’s edible!

One of the most popular species, P. grandiflora, thrives in Zones 4 to 10. It’s a low-growing type that reaches only eight inches or so at full height.

Because it spreads, however, it can create a wide carpet of protection over dry ground where little else grows – sometimes several feet in width.

You’ll see blooms of red, yellow, orange, white, or magenta opening in the summer months, and a lovely blue-green mat of delicate foliage at other times of year.

In warmer regions they’re considered evergreen perennials. But in gardens north of Zone 8, they’ll die off in the winter.

Packets of moss rose seeds with double blooms in a mix of colors can be purchased from Eden Brothers in one ounce and quarter pound sizes.

Learn more about moss rose care here.

14. Mugo Pine

Pine trees are often xerophytic, but often huge once mature, and not everyone has space for a specimen of hulking proportions.

For a smaller garden or landscape, a mugo pine (Pinus mugo), or dwarf mugo pine cultivar such as ‘Compacta,’ can be a blessing.

Another benefit offered by this shrubby species is its range. If the intended site for this specimen is within Zones 2 to 8, it’ll grow almost anywhere, but it is particularly at home in dry, rocky, mountainous regions as a native of central Europe.

Full sun or partial shade is preferred.

A low-maintenance, structurally gorgeous pine like this can easily become the anchor for a bed full of shape and color, or as a windbreak.

Let it grow freeform and create thick, needle-laden branches with upright pinecones developing at the tips in the fall, or prune it for an effect similar to bonsai.

Mugo pine will typically reach about 20 feet in height at maturity, though my parents had one that was still just under 15 feet tall after about 40 years – they’re very slow growing. Dwarf ‘Compacta’ typically attains no more than about four feet in height.

Pick up a dwarf mugo pine (P. mugo var. pumilio) in one-gallon or three-gallon containers, or as a set of six one-gallon containers, from FastGrowingTrees.com.

We delve deeper into mugo pines in our growing guide.

15. Muhly Grass

Muhly grass (Muhlenbergia spp.) might resemble cotton candy clouds like something out of Willy Wonka’s edible landscape, but these fluffy puffs are much tougher than they seem.

The soft, misty panicles that this grassy sedge-like plant produces can range in color from green to white, or even dreamy reddish pink as seen in pink muhly grass, aka M. capillaris.

More than 150 different varieties of muhly grass exist, so you’re bound to find a perfect one for your needs.

Whether you have clay, sand, or even fire-scorched earth in which to garden, this ornamental grass will thrive. Sometimes, it thrives so much that it spreads out of bounds or must be divided, so keep an eye out for the semi-invasive tendencies of these species.

Heat, pests and diseases, deer and wildlife, drought, salty soil – nothing seems to phase it. Add it as a border in an area where the sun sets behind it for a blaze of magical color.\

Muhly grass is also right at home in beds, as a living fence, in a rock garden, and in so many other places.

Most types of muhly grass can reach heights of up to four feet with a similar spread, and pink muhly grass achieves about four to five feet at maturity, so make sure you have enough space before you install these plants in Zones 6 to 11.

You can pick up Regal Mist® pink muhly grass in #5 containers from Nature Hills Nursery. This cultivar is also known as ‘Lenca.’

16. Olive

If you’re looking for a grand-scale specimen that provides shade, structural interest with a gorgeous, gnarly, twisted trunk, and a potential food source as well, then an olive tree (Olea europaea) might be exactly right.

Olive trees are available in fruiting or ornamental types, so if the form is appealing but the fruit is not, you have options. These trees have been cultivated in arid regions, like the southern Mediterranean and the Sahara Desert, throughout recorded history.

Most develop a single trunk, but some, like the ‘Manzanillo’ olive, can develop multiple trunks. They have wide canopies, reaching about 25 feet in width with an equal height.

Plant shade-loving xerophytic herbs like sage, rosemary, and thyme under the canopy or brighten up the planting area with suitable flowers.

Gardeners in Zones 8 to 11 can install most olive trees without issue, since they need full sun, long, hot summers, and sandy, well-drained soil.

However, ‘Mission,’ for example, is one cultivar that can tolerate lows to about 8°F, so this is a good choice for growing a bit further north.

A fruiting ‘Manzanillo’ in a #1 container is available from Nature Hills Nursery.

‘Manzanillo’ olive trees are of Spanish origin, and the fruits of this cultivar have been developed for meaty flesh, an easy to remove pit, and uniform shape and color. It’s the most popular olive in the world for commercial production.

Fruits are produced in the fall, following a flush of small, white blooms. The foliage remains evergreen.

The cultivar known as ‘Swan Hill,’ on the other hand, was bred for beauty without producing olives.

It has the same lovely, gnarled trunk and evergreen foliage as other varieties but it produces a very minimal quantity of pollen, so allergy sufferers may want to consider this as a possible choice.

Learn how to grow olive trees in our guide.

17. Pineapple

Did you know that pineapple plants (Ananas spp.) are succulents in the bromeliad family, Bromeliaceae? Well, they are, and they’re also xerophytes!

Even though the foliage of a pineapple plant isn’t typically as colorful as that of most other bromeliads, the developing fruits are both colorful and gorgeous. Plus, you get pineapples – that’s a pretty good reason to include them in your garden, right?

It can take about two years for a fruit to fully develop, but in that time, the large, toothed leaves can grow to between three and six feet in height with about the same spread.

Several of these grouped together as the background for a brightly planted bed can make a stunning architectural backdrop.

Not everyone is a fan of pineapple, though, so if you’re in that group, there’s still hope! Ornamental species such as the red pineapple (Ananas bracteatus) offer all of the beauty and smaller, less fleshy fruit – though it is still technically edible.

Provide full sun and sandy loam for pineapples. Learn all about growing and caring for them in our guide. (coming soon!)

You can find A. comosus ‘Florida Special’ aka Sugarloaf pineapple available in one- and three-gallon containers from FastGrowingTrees.com.

18. Pomegranate

Adding a fruiting tree to your landscape can take a little more work to maintain, but if you’re interested in having a tree that’s attractive, functional, and productive, then the pomegranate (Punica granatum) is a great choice.

These ancient trees have been cultivated since the Bronze Age, from the first recorded species that appeared in the Middle East.

During the hottest, driest times of year, it’s best to offer some water to prevent cracked fruit, but otherwise, they’re very conservative in their needs.

Ornamental pomegranate trees are also a possibility, if you’d like the appearance without the edible fruits.

Cultivars such as the dwarf ‘Nana’ produce showy blooms, pretty green foliage, and inedible, mini fruits that add interest throughout the fall and winter in warm climates.

Less space is needed to grow them as well – maximum mature height is only three to four feet.

Both the dwarf and full-size species plant and cultivars can typically withstand temperatures in Zones 7 to 11, as long as they’ve got a nice sunny spot to grow, and well-drained, sandy soil to take root in.

Surround them with flowers or succulents in tones of blue and green for a stunning pairing.

In regions north of Zone 7, consider the full-size cultivar ‘Russian 26’ – this cold-hardy specimen can survive freezing and temperatures down to about 5°F! Plus, they produce large, bright red pomegranates in the fall.

Learn more about growing pomegranates in our guide.

You can order a ‘Texas Pink’ pomegranate tree, which reaches a modest height of just 15 feet at maturity and bears pink globe-shaped fruit, in a three- to four-foot size from FastGrowingTrees.com.

19. Prickly Pear Cactus

Yet another entry on our list that offers both form and function is the prickly pear cactus (Opuntia spp.).

A lot of gardeners and plant enthusiasts have at least seen a prickly pear before – also known as opuntia, paddle cactus, and Indian or Barbary fig – but this succulent has some interesting features that not everyone knows about!

Prickly pear fruits and pads are edible, so in a garden that’s designed to pull double duty and offer water-thrifty beauty and food simultaneously, these true cacti fit the bill.

We have dedicated guides with full instructions for you on harvesting both the pads, or nopales, and the fruits, or tunas, including how to process these tasty treats.

Aside from this useful trait, these species, which are indigenous to North, Central, and South America, can withstand incredibly long periods of drought, intense sunshine, high heat, and sometimes, frost or even snow. Talk about a tough cookie!

Plant one of the best-known species with the widest range, O. humifusa, or the eastern prickly pear, in full sun and sandy substrate with good drainage. Avoid overwatering as too much water can actually cause members of this genus to weaken and lose structural integrity.

Maybe you want a specimen that is a showstopper in more ways than one – if so, O. gosseliniana var. santarita, aka O. santarita, or the Santa Rita prickly pear, will surely turn heads.

This species has rounder pads that range from blue-green to bright purple in cooler temperatures, paired with yellow blooms and red fruits.

Most members of this genus are hardy in Zones 7 to 11, but some can be grown as far north as Zone 3. Thorny cacti like these are best set apart from high-traffic areas.

You can have find Santa Rita opuntia pads available from the Legendary Yes store via Amazon.

Or, grab two five-inch pad cuttings of the eastern prickly pear from Amazon.

Check out our guide to learn more about growing prickly pears.

20. Redbud

My parents had an eastern redbud tree (Cercis canadensis) growing in their yard when I was a kid, and I remember the delicate, purplish-red blooms forming every year, for over 40 years, without fail.

Like most redbud trees, it had a single trunk that branched to form a spray-like canopy of color.

The leaves were large and heart-shaped, bright green, and always fun to pick up and play with when we were raking them in the fall, since these trees are deciduous.

Average mature height is between 25 and 35 feet, with about the same spread. When in bloom, they create a cloud of stunning color like no other. They’re also capable of surviving in clay, loam, sand, and alkaline soils, in full sun or partial shade.

Redbud species and cultivars can typically be planted throughout Zones 4 to 9, or sometimes slightly further north or south, depending on the variety.

North American natives like the eastern redbud are great for supporting local pollinators as well, so you could always hang a butterfly house or add a bee waterer at the base as a service to these crucial insects. They’re suited for growing in Zones 6 to 9.

An eastern redbud in a one-gallon container is available from Home Depot.

Find more tips about caring for redbud trees here.

21. Red Pencil Tree

Gardeners who are looking for a distinctive species to act as a can’t-miss focal point in their garden will surely take an interest in the red pencil tree (Euphorbia tirucalli).

With cultivars such as ‘Firesticks,’ you can imagine the color that must have inspired the name.

E. tirucalli is a species sometimes referred to as red fire cactus, pencil cactus, or milkbush, because of the latex sap it can exude when broken – which is highly toxic and should not be touched or ingested.

The cultivar ‘Firesticks,’ aka ‘Sticks on Fire’ lacks the chlorophyll of the species plant. That difference is all it takes to produce a flame-red, orange, and yellow shrub that can reach up to 25 feet in height in ideal conditions.

In cultivation, this species rarely exceeds eight to 10 feet, though, with about the same spread.

Although the red pencil tree isn’t a true cactus, it definitely has the appearance of one – or perhaps it more closely resembles a huge branch coral growing in the front yard, in Zones 9 to 11.

The thin branches are about as thick as a pencil, a trait which inspired its common name, and tend to become more yellow in high heat and more red in cooler seasons.

Bring this specimen home to a position in the garden where it receives full sun, good drainage, and low humidity, but avoid contact with people or pets.

Order a six-inch, bare root ‘Firesticks’ pencil cactus from Hirt’s Garden Store via Amazon.

22. Red Yucca

Red yucca, sometimes known as false or coral yucca, or Hesperaloe parviflora, is not actually a true yucca, but rather a member of the Asparagaceae family, along with agaves and thousands of other species.

This evergreen perennial semi-succulent probably earned the misnomer because it certainly behaves like a yucca, at least in form, with long, narrow leaves that grow in a tuft and long stems which bear small red blossoms.

Tufts of long, slim, arching leaves form at ground level, reaching four to six feet in width.

Long-stemmed inflorescences four to five feet in height sprout in spring and summer, curving slightly above the blue-green foliage as the blooms open. Winter foliage may have a slight purple tinge.

If that’s a bit too large a size for the planned site, consider the smaller cultivar known as ‘Brakelights,’ which exhibits the same features in a more compact, three-foot-wide specimen of equal height.

Both the species plant and its cultivars are excellent sources of forage for pollinators such as butterflies and hummingbirds.

Add yours to the garden in sandy, well-drained soil where it will receive full sun to partial shade in Zones 6 to 11, but be sure to avoid handling it too much as this species is known to cause skin irritation.

Snag a one-gallon grower’s pot of red yucca from Amazon.

23. Silver Mound

Fill in edges, borders, or large areas with mounded tufts of silvery, lacy foliage by growing silver mound (Artemisia schmidtiana).

Sometimes referred to as dusty miller, wormwood, or ghost plant, perennial artemisia adds a lush yet wispy look to a variety of spaces.

In Zones 4 to 8, mounds can reach about 10 to 14 inches in height and width. Known to be deer, drought, and heat tolerant, sprigs of this plant are commonly added to floral arrangements because of the gorgeous structure of the foliage.

Sites that have well-drained, sandy substrate are best for this species, and full sun is preferred.

Group silver mound together with other xerophytes of varying heights, such as muhly grass, euphorbia tree, and blue chalksticks, for a tranquil color palette and dense ground cover.

A seasonal trim in the fall can remove dead or dying summer blooms, which are tiny and yellow, and help to keep growth in check in the spring.

Some gardeners prefer to trim buds off before they open. Cut them down to about five inches in height – this will also maintain the mounded form.

Note that some allergy sufferers may have trouble with the significant quantities of pollen this species produces, and some a slight rash may develop on contact in some people.

However, this herb is very aromatic and for those who don’t have allergies, the scent adds another layer of interest.

Find silver mound in four-inch pots, available from Winter Greenhouse via Walmart.

24. Snake Plant

A succulent variety that doesn’t look like one is an interesting find, and a nice addition in spaces where shape and color are the main focus. Enter: the snake plant (Dracaena spp.).

Gardeners who are familiar with these species may already know that they were once classified as Sansevieria, but incorporated into the Dracaena genus more recently as the result of genetic research.

Snake plants come in a wide range of shapes and sizes – so many, in fact, that we have an entire roundup dedicated to their amazing diversity.

You might like to choose the most popular species, D. laurentii, as an outdoor specimen that can reach three feet in height or more.

For some serious architectural appeal, try D. bacularis ‘Fernwood Mikado.’ With a cylindrical form, this cultivar sports tall, thin, tube-like leaves that resemble lively branches.

Use them to add interest to a lackluster space like a large, boring wall, or as the framing background of a colorful bed.

In Zones 9 to 11, almost any species or cultivar can be grown in soil that drains well, and in either sun or shade. One of the best things about growing snake plants is that they aren’t finicky – they’ll quickly fill out a bed over time and thrive even with neglect.

Note that, in some environments, snake plants can become invasive if they’re left to spread beyond the borders of their bed. Keep them in check by pulling up any offshoots that stray – they make great houseplants, too.

Try a gorgeous, silvery-green cultivar like ‘Moonshine,’ available in a 10- to 12-inch size from Burpee.

A classic D. laurentii, or golden snake plant, is also available in a 10- to 12-inch size from Burpee.

25. Texas Mountain Laurel

Texas mountain laurel (Sophora secundiflora), sometimes known as mescal or frijolito, is a blooming evergreen tree that typically forms multiple trunks.

As a member of the Fabaceae or pea family, its foliage and blooms resemble those of other members of the Sophora genus, with dark green, leathery, compound leaves, and weeping clusters of blue to lilac blossoms.

The fragrant, showy flowers are an excellent addition to a garden with other wildflowers, shrubs, and cacti. Since this tree rarely reaches more than about 15 feet in height at maturity, it makes a great choice for adding shade, color, and a pleasant scent.

Native to Texas and New Mexico, this species prefers rocky, sandy soil and powers through drought conditions with ease. Be aware, however, that the seed pods produced after pollination contain bright red, toxic, bean-like seeds.

Expect buds to develop in late winter to early spring. This specimen is best suited for conditions in Zones 7 to 11. Check with your local garden center for availability.

26. Texas Sage

For a non-succulent, shrubby, colorful choice, Texas sage (Leucophyllum frutescens) can’t be beat! This absolutely enchanting species can be trained into a spray, small bush, trailing mass, or privacy barrier, making it an excellent option for many gardeners.

Soft, silver-gray leaves add interest throughout the year when the flowers aren’t in bloom. In summer and fall, the small blooms load stems with pale pink, dusky purple, and indigo blue tones.

Plant Texas sage in sunny, dry, and sandy beds, along borders, or between yards for massive impact – but be prepared to provide a trim now and then to keep them shapely, as they sometimes grow to be a big scraggly.

Zones 9 to 11 are best for this species, which can reach up to six feet in height with an equal width at maturity.

Texas sage is available in quantities of three, 10, and 20 plants via Amazon.

27. Velvet Mesquite

Trees that thrive with less water are a wonderful choice to include in the garden. One tree of choice is the velvet mesquite (Prosopis velutina), an Arizona native species.

The Prosopis genus is part of the Fabaceae family, also known as the legumes – that’s right, like beans and peas. And, just like its cousins, the flowers and beans they produce are edible, and they also add nitrogen to the soil as a bonus!

Several mesquite species are common, non-succulent additions to xeriscapes and xerophytic gardens for several reasons.

They remain fairly small and may be considered understory trees or large shrubs. Reaching about 30 feet in mature height, with a 30- to 40-foot spread, they seem to hit the sweet spot in landscaping by providing low water consumption combined with adding shade, and a gorgeous, semi-weeping form.

Delicate, fern-like foliage with small leaves and short, gnarly, single or multiple trunks add interest. Densely packed yellow blooms appear in spring and summer on two- to three-inch-long weeping spears known as catkins.

Note that mesquite trees are deciduous, typically dropping leaves and producing long seed pods in fall and winter.

Beware of the thorns that appear between leaf nodes – if you’re looking for a tree to place near play or traffic areas, this may not be the best choice.

While this species is hardy in Zones 6 to 9, other types, like Chilean (P. chilensis) and honey mesquite (P. grandulosa), can be grown in Zones 9 to 11.

Less Water, More Beauty

Wow! What an incredible assortment of options! Have you added any of these to your planting list? Let us know!

Water-conscious landscaping doesn’t have to be boring, brown, or uninviting. And even though this may seem to be a substantial list, our roundup is really just a small inventory.

There are many more xerophyte species and cultivars that can be included in your landscaping plan.

What are you growing, or thinking of adding to your outdoor spaces? Drop us a line in the comments below! And feel free to get in touch if you have any questions.

If you’re still on the lookout for drought-resistant or drought tolerant plants to bring home, consider these as well: