Pinus mugo

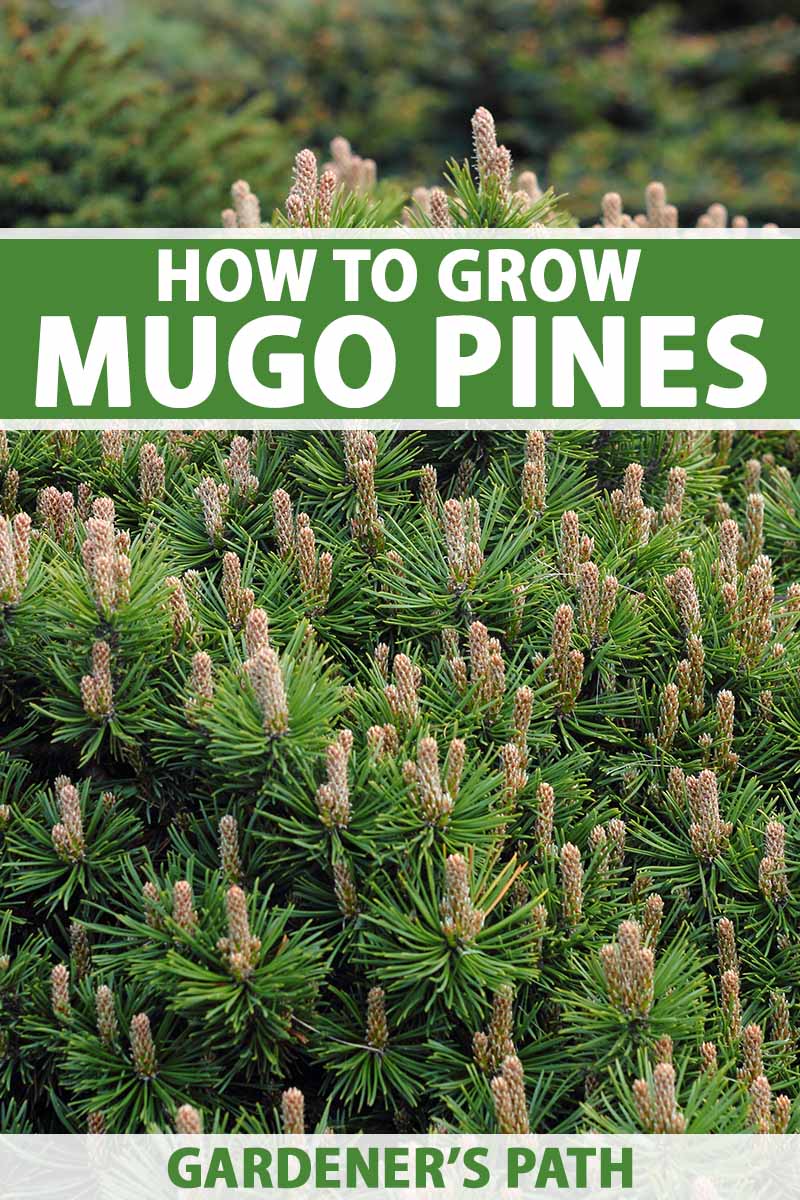

Mugo pines can’t be beaten if you’re looking for something to add texture and year-round interest to the garden. The long needles are distinctive, even more so when they’re variegated or those that change color.

That’s right, some cultivars have needles that change color from summer to winter. Instead of dropping from the plant like deciduous leaves, the color alters from season to season.

Mugo pines come in a wide range of sizes, from itty-bitty dwarf shrubs to towering trees.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

Also known as creeping pine, mountain pine, or the rather uninspiring monkier of bog pine, part of what makes mugo pine such a stellar garden option is that it only sheds its needles once every four years.

If you’ve ever spent the weekend raking up needles from the lawn or picking them out of your feet when you walk outside barefoot, you appreciate what a treasure a pine that doesn’t shed frequently is.

Thriving in USDA Hardiness Zones 2 to 7, this species is tough as nails when it comes to the cold. It’s not as fond of the sweltering heat, though.

Whether you need something for a rock garden, to fill a pot on your patio, or as a reliable specimen tree in your lawn, you know a mugo will have you covered.

Ready to learn all about this evergreen stalwart? Here’s what we’re going to go over:

What You’ll Learn

Incidentally, mugo pines have a bit of a reputation for not sticking to their advertised size. When you’re planting a dwarf tree, you want it to stay dwarf.

But more than one person I know has found themselves digging up a tree that turned out to be nothing like what they expected.

If you’ve heard the stories and you’re a little nervous, don’t worry. We’ll discuss this and how to avoid it.

But first, let’s talk about this plant’s history.

Cultivation and History

Mugo (pronounced mew-go, not moo-go) pines are indigenous to mountainous regions of Europe. You’ll find them growing wild in the Alps, the Pyrenees, the Carpathians, and other mountainous regions in the Balkan Peninsula.

They have also naturalized throughout Scandinavia and Finland, where they were originally imported to help with erosion control and as ornamentals. Now, the mugo pine is considered invasive in some areas of Europe.

The mugo pine typically grows from 3,000 feet above sea level to the tree line, though it is found in lower elevations in modern Germany, Poland, and Bulgaria. It’s also cultivated at much lower elevations.

In the wild, it rarely reaches more than 20 feet tall, usually remaining much smaller.

It’s no wonder that people started cultivating it to use in gardens, since you can enjoy the evergreen splendor of a pine without having to plant a massive tree that takes up a lot of space.

The shrubs are typically about twice as wide as they are tall, but as there are many cultivars out there, there can be some variation in their shapes.

Underneath the three-inch-long stiff green needles, that grow in bundles of two, is grayish-brown, scaly bark. The cones are up to two inches long and may appear in clusters or singly.

The reason that you can find so many mugo pines in gardens across the globe owes itself to the fact that mountaineering took off in the Western world in the mid-1800s.

As people scaled the challenging slopes of Europe, they came back with an admiration for the rocky alpine gardens and the plants that inhabited them.

Good old mountain pines were one such species. Their popularity began to spread rapidly throughout the rest of Europe beyond their native range and across the pond to North America, where they first appeared in nursery catalogs around the turn of the 20th century.

Today, you can find them at practically every nursery.

Mugo Pine Propagation

It’s possible to grow mugo pines from seed, though they might not grow as an exact replica of the parent plant.

If you don’t mind a surprise, then visit our guide to growing pines from seed to learn all about the process.

If you want to be certain about the results, you can propagate pines from cuttings or purchase a plant from just about any nursery.

Starting new trees from cuttings is a slow process, but it’s fairly reliable.

During the winter, when the plant is dormant, take a six-inch softwood cutting from the tip of a branch and place it in a container filled with moist potting medium. Keep the potting medium moist as you wait for roots to grow.

Fall or spring is the best time to transplant a purchased tree. Dig a nice-sized hole about twice the width and depth of the container the plant is currently growing in. Remove the tree from the container, loosen up the roots, and place it in the hole.

Fill in with soil and ensure that the tree is sitting at the same height that it was in the container. Then, just add water! The soil should be moist but not wet. If the soil settles, add a bit more.

Learn more about starting pines from cuttings and transplanting in our guide to growing pines.

How to Grow Mugo Pines

Mugo pines don’t grow in hot, arid regions in the wild. If you live in the desert, it doesn’t mean you can’t grow this plant, you’re just going to need to pay particular attention to irrigation. They prefer consistently moist soil.

Moist doesn’t mean wet. If you were to grab a handful of soil and squeeze it in your hand, it would fall back apart when you open your hand, and no water would squeeze out.

That’s what you’re aiming for. If you squeeze the soil and it sticks together and water drips out, the soil is too wet.

If you are concerned that you’re overwatering, you probably are. These plants will do better if you err on the side of too dry rather than too wet.

If the top inch or two of soil dries out between watering, it’s totally no big deal. But aim to keep the soil consistently moist if you can without overwatering.

The soil absolutely must be well-draining. If you don’t have well-draining soil, it’s best to grow a dwarf type in a container or plant in a raised bed. You can also amend your soil really well, but you’re going to have to dig deep and make sure you plant a dwarf type.

Dig down at least four feet and mix in as much well-rotted compost as you need to make your soil well-draining.

A little bit of clay in the soil is fine, as is a bit of sand. Mugo pines will adapt to either. They can also grow in acidic and slightly alkaline soil, with a pH anywhere from 4.5 to 7.5.

While they tolerate as little as four hours of sun per day, they do best with a full eight hours or more of full sun. This is doubly true for the types that change color. You will see much better color variation in full sun.

Mugos appreciate a bit of food, but don’t go overboard. In the spring, heap well-rotted compost around the plant inside the drip line, just make sure it’s not touching the trunk or stems. That’s it!

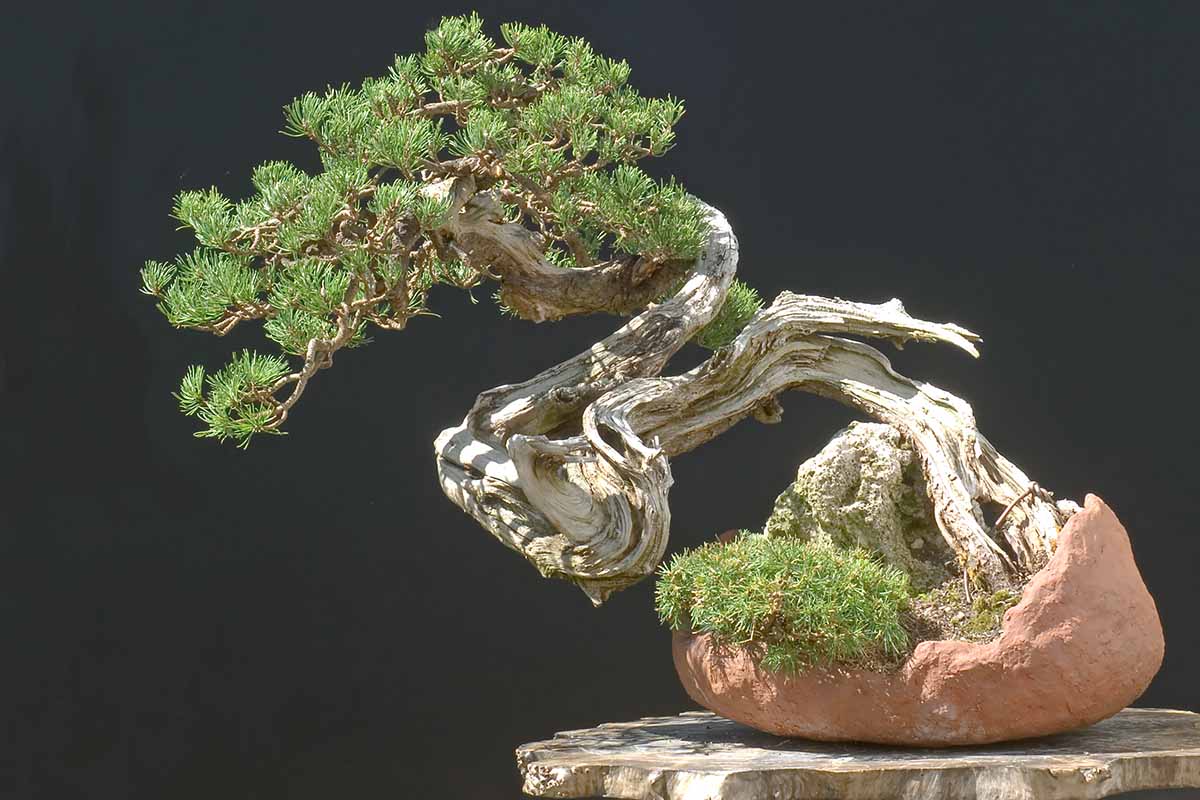

Smaller cultivars lend themselves beautifully to container growing. Depending on the size of the mature tree, you can grow mugo pines in something as small as a bonsai container.

Some of the small cultivars, which we will discuss shortly, could grow comfortably in a 12-inch diameter pot. The key is to find a container heavy enough that it can support the mature plant, especially if it’s an upright type.

Aim for a container that is about the same predicted width of the mature plant and one that is made out of a heavy material like clay or cement.

Whatever you choose, it needs drainage holes. Fill the container with any old water-retentive potting soil.

With container growing, you need to keep a close eye on soil moisture. Containers tend to dry out more quickly than soil in the garden.

Growing Tips

- Plant in full sun or partial shade.

- Fertilize with well-rotted compost in the spring.

- Grow in well-draining soil.

Pruning and Maintenance

Mugo pines can be kept more compact using a method known as candle pruning. The “candles” that this method references is the new growth at the tips of the branches.

This new growth is brighter than the old growth and the “candles” are typically straight, with the needles tucked together, rather than open.

Just grab one of these and snap it off. Don’t worry, they’re soft.

This prevents the new growth from growing too long and adding any length to the branch.

There’s no need to prune otherwise unless you want to provide a little shape to your plant. If you must prune off any dead, dying, or diseased limbs, remove the entire branch, but be sure to leave the branch collar intact.

The branch collar is a swollen bulge where the branch meets the trunk.

Mugo Pine Cultivars to Select

There are three subspecies of P. mugo. These are mugo, uncinata, and rotunda.

P. mugo subsp. mugo grows in the eastern and southern part of its native range, and the subspecies uncinata covers the western and northern part of the range.

Rotunda is a naturally-occurring hybrid of uncinata and mugo that developed in the region where both subspecies overlap.

The mugo subspecies is the one from which most modern garden cultivars are bred. It grows to about five feet tall and ten feet wide with a rounded shape.

Nature Hills Nursery carries this understated classic in #3 containers.

These pines are sometimes mislabeled as muhgo, but they refer to the same plant.

You can find cheap mugo pines all over the place, but beware that if the plant is listed as a generic “dwarf,” you will possibly end up with a full-sized specimen.

My grandma had a pair of so-called “dwarf” mugo pines that grew so large that she swore off any plant that claimed to be “dwarf” for the rest of her life. She didn’t trust them.

If you want a plant that will stay petite, look for a vegetatively propagated named cultivar. Those grown from seed can vary massively in size.

Here are a few lovely cultivars that will grow to a predictable size (with one exception):

Aurea

Remember how we talked about color-changing mountain pines?

‘Aurea’ is a semi-dwarf cultivar that changes colors, so it provides a surprising shift in tone as the seasons change.

It has golden-green needles in the spring and summer, changing to golden yellow in the fall and winter.

‘Aurea’ grows to about six feet tall and twice as wide with an extremely dense, mounding growth habit.

Carstens

Teeny tiny in size, but big and bold in color, ‘Carstens’ has green needles in the summer that change to bright golden yellow in the fall.

It also remains under two feet tall and wide with a nice rounded shape, but it can even stay as small as a foot tall and wide without any pruning, especially if you grow it in a container.

Maple Ridge Nursery has this cute little color-changer in a gallon pot option.

Golden Mound

‘Golden Mound’ is another one of the magical color-changing cultivars.

In the summer, the leaves on this mounding dwarf variety are green, but they transition to a golden-yellow hue in the winter on a plant that stays under three feet tall and four feet wide.

Pumilio

P. mugo var. pumilio is an extremely common variety thanks to its naturally occurring dense, compact growth habit.

It stays low to the ground and occasionally takes on a prostrate growth habit, but typically has upright growth. Once mature, it’s capable of reaching five feet tall and ten feet wide.

This is one of the “dwarf” mountain pines that can get people into trouble because it is usually sold as a dwarf that only grows three or four feet tall, and it might stay that size, but you can expect it to grow a few feet larger in both directions.

That’s because it’s a variety, not a cultivar, which means it wasn’t selectively bred to have a specific appearance. It is a natural variation of the species that occurred on its own.

It still has its wild genetic heritage, making it a bit less predictable than cultivars selected for specific traits.

Don’t let that put you off. This is a popular option for good reason – it’s robust, reliable, and good-looking. Snag one at Fast Growing Trees.

Slowmound

‘Slowmound’ isn’t quite as cold hardy as its relatives. It can grow as far north as Zone 3 or even Zone 2 with some protection.

Sorry to those in the Alaskan interior, you’ll need to try a different cultivar. For the rest of us, this plant has slightly darker needles than the species and stays petite at just four feet tall and six feet wide.

The needles are also shorter than the species, growing to just over an inch long, giving the plant a more furry appearance.

Planting Tree carries this pretty option.

Sunshine

‘Sunshine’ is so cool. It’s one of my favorites because it reminds me of a porcupine. If you look closely at the quills on the back of a porcupine, they are usually striped, with dark ends and lighter banding towards the base of the quill.

‘Sunshine’ has similar variegation, with green tips and bands of creamy white or yellow alternating with green all the way down the needle. It’s a petite option with a nice round three-foot shape.

Grab one (or, better yet, a group of three) in gallon- or three-gallon pots at Maple Ridge Nursery.

Tennenbaum

Like a perfect Christmas tree, ‘Tennenbaum’ has an upright, pyramidal habit that reaches about 11 feet tall and five feet wide at maturity with a single main trunk rather than the typical multi-stem growth habit of other mugo pines.

It was found in a nursery bed at South Dakota State University.

It holds its deep green color well all year long.

Managing Pests and Disease

So long as you place them in the right growing environment, these plants are pretty problem-free.

These aren’t one of those plants that inevitably experience some kind of issue.

With something like roses or apple trees, you know you’re probably going to have to address a pest or disease issue (or both) at some point.

But a mugo might go its whole life without ever experiencing any trouble.

Plus, herbivores ignore them. Let’s discuss a couple of pests that may bother your plants.

Pests

There are two main pests to watch for:

Pine Needle Scale

Scale are insects that suck the sap out of plants. In pines, it’s the pine needle scale (Chionaspis pinifoliae) that you need to watch out for.

As the name suggests, these pests feed on the needles of the tree. When viewed from a distance, the needles will appear to have turned lighter in color or perhaps have some sort of white coating.

You might not even notice a small infestation, but in home gardens, a small one can rapidly turn into a big infestation.

If you look closely, you’ll see the insects lining the needles. The females are about an eighth of an inch long, and the males are about half that.

They’re essentially stationary, finding a spot on the needle to latch onto and feed. As they feed, the needles turn yellow or brown and drop from the plant. As the infestation progresses, the branches start to die, usually starting with lower branches.

You should make it a rule to inspect your pines closely once every three or four months. It’s easy to treat a small infestation, but a large one can be a battle, and the plant will look worse for the wear.

If you identify scale, treat them right away using insecticidal soap or neem oil. Both work well so long as you follow the manufacturer’s directions.

It’s always handy to have one or both in your gardening toolkit. If you don’t already have some, visit Arbico Organics for 32 ounces of ready-to-use insecticidal soap from Monterey.

Pine Sawfly

The European sawfly (Neodiprion sertifer) is a common pest, especially on mugo pines. The females insert eggs into the needles in the fall. To the observer, it looks like a bunch of brown or tan lumps on the needles. Again, this is why it’s important to inspect your plants regularly.

In the spring, the inch-long green-gray larvae emerge and start chowing down on the needles. They move in groups, stripping the needles from a branch before moving on to the next one. They then pupate and emerge as black flies to start the cycle over again.

When you see the larvae, you can put on a glove and wipe them off the branch and into soapy water.

If you identify the eggs in the fall, cut the infested branches off the tree.

I know they look like caterpillars, but they aren’t, so caterpillar-targeting insecticides won’t work. Something like insecticidal soap, which targets sawflies will work, so long as you apply it when the larvae are present.

Disease

If you grow your plant in a full sun location with well-draining soil, chances are low that you’ll come across this disease. But you should be aware of it.

Dothistroma Needle Blight

Dothistroma needle blight is a fungal disease caused by Dothistroma pini. At first, it shows up as dark spots on the needles. As the disease advances, these spots turn yellow and then turn rusty brown. Finally, the tip of the needle dies.

At any point, you might see tiny black specks, which are the fungal spores, on the needles.

In huge trees, it’s not such a big deal, but in small mugo shrubs or young specimens, the disease can kill a plant outright.

Treatment will typically take a few years because fungicides will prevent the spread, but won’t eradicate an existing infection. So you have to keep at it until the infected needles drop.

Speaking of, be sure to remove any fallen needles and dispose of them in the trash to avoid spread.

Spray your tree once in the late spring with copper fungicide. Then, spray again four weeks later. Repeat this every year until the symptoms are gone.

Bonide Liquid Copper Fungicide

Don’t already have copper fungicide in your gardening toolkit?

Arbico Organics carries Bonide’s Liquid Copper in 32-ounce ready to use, 16- or 32- ounce ready to spray, and 16-ounce concentrate.

Best Uses for Mugo Pines

Mugo pines are hugely popular as a bonsai option. The long needles contrast really nicely with the petite shape. They also lend themselves well to shaping.

I mean, check out this twisted version at Bonsai Boy. It’s destined to be a dramatic specimen.

The dwarf types are perfect for rock or Japanese gardens, as well as for growing in containers.

Both the full-sized and dwarf types make excellent specimens or hedges, depending on your needs.

Have you ever tried mugolio or pine cone syrup? That’s made out of the buds of mugo pines.

It’s incredibly delicious, with a honey-like flavor with notes of pine and maple.

You can buy some in a 3.6-ounce jar at Amazon or make your own by combining pine buds and honey and allowing the mixture to steep for six weeks. Then you filter out the buds and you’re left with a tasty treat.

The needles also make a delicious and nutritious herbal tea.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Evergreen tree or woody shrub | Foliage Color: | Green, cream, yellow, gold |

| Native to: | Europe | Maintenance: | Low |

| Hardiness (USDA Zones): | 2-7 | Tolerance: | Some drought, some clay, some sand, pollution |

| Bloom Time/Season: | Evergreen | Soil Type: | Sandy to loamy clay |

| Exposure: | Full to partial sun | Soil pH: | 4.5-7.5 |

| Time to Maturity: | 10 years (depending on cultivar) | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Spacing: | 6 feet (depending on cultivar) | Attracts: | Birds |

| Planting Depth: | Same depth as container (potted plants), 1/4 inch (seeds) | Companion Planting: | Azalea, deadnettle, hosta, rhododendron, sedum, wintergreen |

| Height: | Up to 20 feet | Uses: | Bonsai, containers, hedge, Japanese garden, rock garden, specimen |

| Spread: | Up to 30 feet | Family: | Pinaceae |

| Growth Rate: | Moderate | Genus: | Pinus |

| Water Needs: | Moderate | Species: | Mugo |

| Common Pests and Diseases: | Sawfly, scale; Dothistroma needle blight | Subspecies: | Mugo, rotunda, uncinata |

Make Room for a Mugo

If your garden is lacking some texture and evergreen color, in a shape that ranges from low-growing and round to tall and pyramidal, I dare you to find something better than a mugo pine.

Are you going to plant something big and bold? Or one of the many dwarf options? Is ‘Sunshine’ calling your name? Let us know which you’re going to grow and how you intend to use it in the comments.

And if you’re interested in learning more about pines, have a read of these guides next: