Frangula californica

California coffeeberry, also known as California buckthorn, is an excellent choice for drought-tolerant wildlife gardens.

This species can grow up to 15 feet tall and spread over 10 feet in width, making it ideal for filling large spaces.

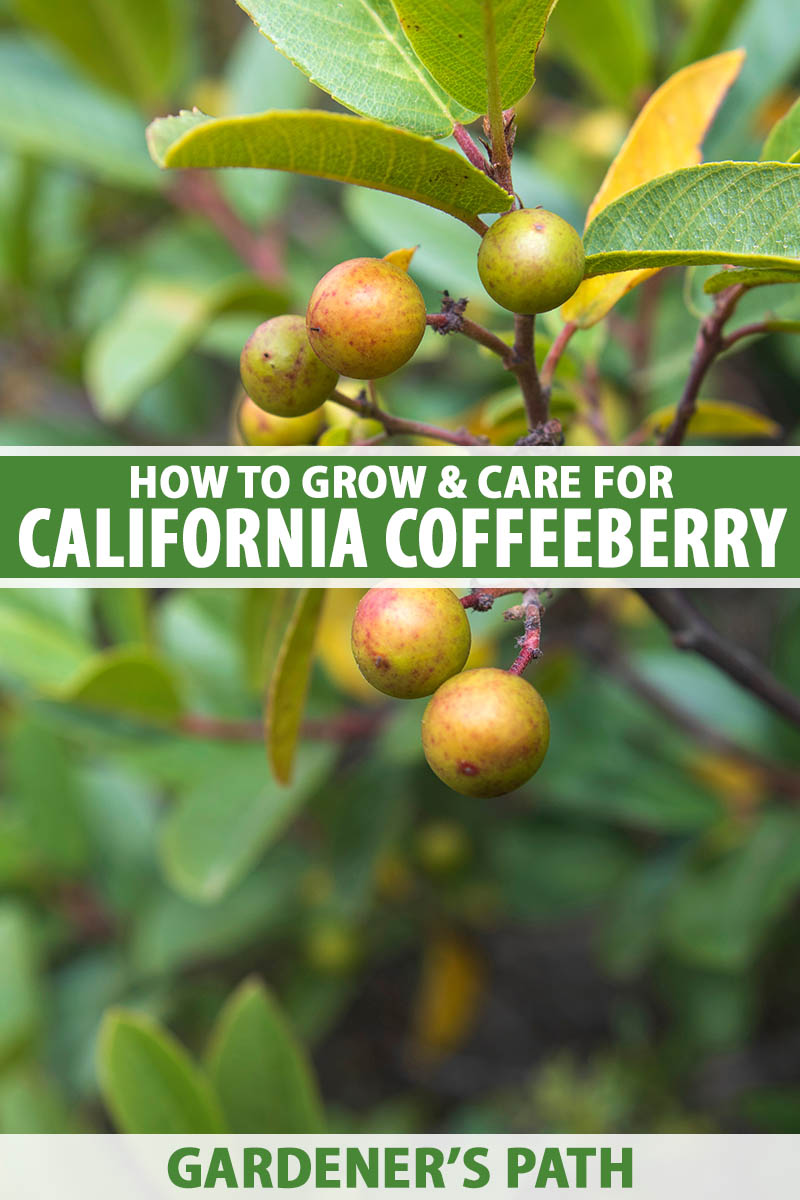

The shiny evergreen leaves are a dark green when grown in the shade, and when given more sun, they are a lighter green. Both shades make for an attractive lush background.

In addition, the reddish-colored twigs and berries contrast beautifully with the foliage.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

This fast-growing native perennial blooms from late spring through early summer, attracting pollinators. The berries ripen in midsummer to early fall, providing native birds like towhees, robins, and thrashers with food.

In addition to being a suitable choice for growing in wildlife gardens, this native plant is also beneficial in restoring dry, steep hillsides by helping to control erosion.

With a dense growth habit, this species is easy to maintain with annual pruning, and it’s rather impressive in drought conditions.

Quite a few low-water native plants are flammable, but not California coffeeberry!

The Orange County Fire Authority suggests coffeeberries for arid landscapes because they can help slow encroaching fires, thanks to the plant’s dense growth and being less prone to burning. These plants are also quick to return after severe wildfires and will reestablish their pre-fire size in no time.

We can bring more harmony to ecosystems by adding native plants to our landscapes that support local wildlife and insect species while saving water during droughts and restoring the soil.

Grow your garden’s native plant community by including this habitat-friendly flowering perennial that birds love!

Continue reading to learn more about this adaptable and resilient shrub and how to easily cultivate it in USDA Hardiness Zones 7 through 10.

What You’ll Learn

Cultivation and History

California coffeeberry is a member of the buckthorn family, Rhamnaceae. To help avoid confusion when sourcing this plant, it’s important to know that Frangula californica was previously classified as Rhamnus californica.

Coffeeberries can live for 100 to 200 years in ideal conditions. This long-living plant is native to California, Oregon, Nevada, Arizona, New Mexico, and Baja California, and it can be found growing in coastal sage scrub, chaparral, forest, and central oak woodland environments.

The seeds of this species resemble coffee beans, which gives us the common name California coffeeberry. But this plant should not be confused with Coffea arabica and other species known for producing coffee, or with Rhamnus cathartica, the common buckthorn.

F. californica berries start out green, turn red as they mature, and change to black when they are ripe. It sure is a stunning display when the berries are black and red simultaneously!

Thanks to its abundance, there are many versatile uses for this native plant. The bark, leaves, berries, and seeds are used as food and medicine by Indigenous peoples.

The Chumash and other Indigenous communities use the fresh berries and aged bark as a laxative and purgative.

Leaves are used topically to treat various afflictions. For example, mashed berries combined with sap and leaves are applied to stop bleeding and heal wounds, sores, and burns by the Kawaiisu people. The Mutsun call the berries puruuric and eat them fresh.

When the seeds are dried and ground, they can be brewed into a beverage that tastes like coffee. The drink does not contain caffeine, but it can have similar laxative effects.

Propagation

Sowing seed is best as opposed to rooting cuttings, and gathering seed is a gratifying activity that helps you connect with nature and native plant communities.

If you prefer to propagate from cuttings, the survival rate will be lower than starting coffeeberry from seed. According to the Native Plant Network Propagation Protocol Database, the expected survival rate when transplanting cuttings is 50 percent compared to 80 to 90 percent when transplanting seedlings.

As long as you are aware of this, you can plan ahead by increasing the number of cuttings you take to propagate. We’ll share some tips below.

From Seed

Starting seeds within this plant’s native range is recommended, which is what we will cover here.

The seeds are easy to germinate. However, a bit of patience is required beyond successful propagation, as this species matures slowly. But remember, California coffeeberries can live for hundreds of years, so I’d say that’s a fair trade-off.

Seeds can be collected in late summer through early fall. Once the berries are soft, black, and easily removed from the stem, they are ready. Each berry contains one to two seeds.

Crush the berries to collect the seeds and rinse them with water until they are clean, using a sieve so you don’t lose them.

Fresh seeds can be sown right away without having to cold stratify them. However, dried and saved seeds will require two to three months of cold stratification.

When storing your seeds, dry them thoroughly so they don’t rot. They should remain viable for nine months when stored in an airtight jar kept in the refrigerator.

You can direct sow in the fall or early winter. First, clear any plant debris from your desired planting area and place the fresh seed a quarter to a half an inch deep into the soil. If sowing more than one seed, space them 10 to 15 feet apart. Gently cover with soil since they will not germinate when buried deep.

Make sure they stay moist but are not overly saturated. If there is minimal rainfall, water the area twice a week until seeds germinate, in approximately 45 days.

As mentioned above, sowing saved seeds will require two to three months of cold stratification.

To begin the cold stratification process, first soak the seeds in water for 24 hours, then place them in a zip-top plastic bag with equal amounts of perlite that has been moistened but not drenched.

Every few weeks, you’ll want to check on your bag of seeds to make sure the medium is still moist and that there is no mold growing. If you notice mold growth, you can wash the seeds in diluted hydrogen peroxide, replace the perlite, and place the seeds in a new plastic bag.

Seeds typically germinate in 45 days. Once you notice that the radicle that has emerged from each seed is at least a quarter of an inch long, they are ready to be planted.

Sow seeds in individual containers that are at least one and a half inches wide and five inches in height.

Deep Rootrainer seed-starter containers encourage healthy root growth and these are the perfect size! The cells have a hinge that allows you to observe root development without harming the plant.

Packages of 32 cells with a holding frame and humidity cover are available from Gardener’s Supply Company.

Use a standard potting mix to sow your seeds. Moisten the medium without oversaturating it, and fill your individual containers.

Be careful to not disturb the radicles when planting. Sow a quarter to a half an inch deep with the radicle facing downwards.

Seedlings will be ready to plant in their permanent location as described below in two to three months.

From Cuttings

In winter, gather hardwood cuttings that have at least four nodes and are a quarter of an inch in diameter.

Wearing protective gear, dip your cuttings in a mild bleach solution.

Leave one leaf in place above the top node, and remove the rest. Make a cut at a 45-degree angle before the last node at the base of each cutting.

Fill one-gallon containers with three parts perlite and one part vermiculite.

Poke holes in the medium with a stick or dibber that’s slightly larger than your cuttings. Place the cuttings two inches deep into the holes you poked, with at least two nodes buried. You can place five or six cuttings in one container.

Keep the medium moist throughout the rooting phase.

You can leave the cuttings outdoors all winter and into spring. But be sure to give them shelter during winter storms.

In approximately 60 days, you can check for substantial root development. Once you observe a robust root structure, you can transplant them.

Transplanting

I suggest transplanting your seedlings in winter so they can benefit from seasonal rains in their native range before experiencing their first summer outdoors.

This will allow them to focus on root development rather than putting their energy toward growing foliage.

You could also transplant them into a five-gallon pot that can be placed outdoors and moved into the shade if summer temperatures are too intense for your first-year plant.

You can then transplant into the ground in fall, which is the best time to plant native species in California, Oregon, Arizona, Nevada, New Mexico, and Baja California.

Push mulch or any other organic matter away from your planting location to have access to bare soil. Dig a hole a little bit deeper than the plant’s root system and twice as wide.

Fill the hole with water and allow it to drain. Carefully turn your container upside down to remove the plant.

Next, place the plant into the hole and fill any open spaces back up with native soil. Bring the mulch back over the bare soil but make sure it does not touch any part of the plant, leaving at least six to eight inches clear around the stems.

If you are planting more than one, space them at least six feet apart – this will soon provide you with a hedge! Plant them 10 to 15 feet apart if you don’t desire a hedge but still want to grow multiple plants in the same area of the garden.

Give them a deep watering after planting.

How to Grow

Once established, coffeeberry practically grows itself! These shrubs are considered fully mature when they begin to flower, and produce berries in two to five years.

They will grow in partial shade to full sun in well-drained soil with a pH of 5.0 to 8.0. This shrub is adaptable and can be cultivated in chalk, clay, loam, and sand.

Provide at least three inches of moisture-retaining mulch to help them thrive in hot and dry conditions. A mulch comprised of pine, oak, or other native tree chippings is best for native plants.

Generous amounts of leaf litter are typical in the native habitats where they flourish.

In their first few years of growing in the garden or landscape, they will benefit from two deep waterings each month in the absence of rain. Though drought-tolerant, occasional summer watering in the plant’s first and second year is recommended.

Growing Tips

- Plant in the fall to develop strong roots.

- Apply at least 3 inches of mulch around plants to help retain moisture.

- Watering during dry periods in the first and second summer of the plant’s life will help it thrive.

Pruning and Maintenance

F. californica responds well to pruning. If your shrub becomes too large or dense, it’s easy to manage its growth. These plants adapt so well to pruning that they are often used as hedges.

You can trim their branch tips to shape coffeeberries and manage their form. Pruning is best done in summer when conditions are dry, providing an environment that is not conducive to the spread of disease.

Prune away any dead or diseased branches by cutting them close to the shrub’s trunk or back to a more vital branch.

Because coffeeberries are one of few forage sources available in the fall for birds, the berries don’t go to waste! Native birds do a fantastic job keeping the ground free of berries, so you don’t have to.

Also be sure to maintain a generous layer of mulch, as mentioned in the how to grow section above.

Cultivars to Select

One of my favorite times of the year is when native plant sales happen in my area in the fall! Most perennial native plants available at nurseries have well-established root systems, because they are already at least one year old.

There are a few coffeeberry cultivars to choose from that will provide you with different size options. Below, I’ll highlight various varieties, starting with the most compact and ending with a shade-loving cultivar.

‘Little Sur,’ as the name suggests, is a small variety perfect for compact spaces. This cultivar has dark green foliage and is just three to four feet tall and wide at maturity!

‘Mound San Bruno’ is another compact variety which comes from the San Bruno Mountain area. These can be kept in a five-by-five-foot space with ease, shaped into a hedge, or allowed to create a shrubby ground cover in the garden.

This shrub grows four to six feet tall and twice as wide if allowed to attain its natural form.

‘Eve Case’ is also considered a compact cultivar. This variety grows five to eight feet tall with a similar width, and this shrub’s size can easily be maintained with pruning.

The leaves are a brighter green in comparison to those of other varieties.

‘Bonita Linda’ is a larger cultivar that does well in partial shade. It grows eight to 10 feet tall and wide, with gray-green foliage.

Managing Pests and Disease

This resilient perennial is typically subjected to very few pests and diseases in its native range.

Herbivores

You won’t experience many issues with herbivores, although deer may visit when there’s a shortage of other plants available to forage.

Deer

Deer help disperse the seeds in the wild and tend to forage more during droughts.

If you live in an area that has visiting deer, you can protect younger vulnerable plants by setting up chicken wire around them.

Insects

Once native plant species become established, they help to balance out the ecosystem. When they are young, and if the garden is new, you’ll often have to deal with more pests than beneficials.

Here are a few common types you may encounter:

Aphids

Aphids (Aphidoidea) can be found on new growth or on the undersides of leaves. They are small sap-sucking insects that puncture stems while feeding on the plant.

When they suck plant juices, they leave behind a sticky sap called honeydew that attracts ants and can lead to sooty mold growth.

An infestation can affect the plant’s growth and can usually be managed with a strong spray from the hose.

Read more about how to control and eradicate aphids here.

Whiteflies

Whiteflies (Aleyrodidae) are tiny, sap-sucking insects that can increase in number during periods of warm weather. They get their name from the white waxy covering on the wings and bodies of the adults.

Technically they are not true flies. Instead, they’re related to aphids, mealybugs, and scale. Large populations can cause yellowing of the leaves, sometimes resulting in leaf die-off.

Like aphids, they excrete honeydew that leaves a sticky residue on foliage where black sooty mold can grow.

To control populations, it can help to remove infested leaves as soon as you see them. You can also hose down the leaves.

Learn more about how to control a whitefly infestation here.

Disease

When it comes to disease, this plant sure is resistant! But there is one common disease that is associated with this plant within its native range that we will review below.

Scab

F. californica can play host to fungi which affect the appearance of leaves. Rare cases of plentiful spring rain can promote this disease, while hot and dry weather halts its spread.

Scab disease, caused by Fusicladium, Spilocaea, and Venturia species, will first appear as light spots on leaves, sometimes yellow in color. The lighter spots will turn a shade of dark olive as the disease advances, and fungal growth will appear on the undersides of leaves. They will then twist and eventually fall off.

The best solution for scab is to remove and dispose of fallen leaves. Also avoid getting the foliage wet when watering, like you would with most plants.

Pruning branches to increase air circulation helps improve growing conditions and minimizes humidity.

Best Uses

This impressive shrub sure is exceptional in many ways, from supporting slopes to providing food for wildlife when berries are scarce!

California coffeeberries are the ideal species for wildlife and pollinator gardens within their native range where they can be grown as a hedge, screen, or ground cover.

The shrub is host to ten confirmed butterfly and moth species, including the pale tiger swallowtail (Papilio eurymedon), Western sheepmoth (Hemileuca eglanterina), ceanothus silkmoth (Hyalophora euryalus), and gray hairstreak (Strymon melinus).

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Perennial shrub | Flower / Foliage Color: | Cream-yellow, lime green, off-white/dark to light green |

| Native to: | Baja California, Arizona, California, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon | Maintenance | Low |

| Hardiness (USDA Zone): | 7-10 | Tolerance: | Drought, fire |

| Bloom Time: | Late spring-early summer | Soil Type: | Chalk, clay, loam, sand |

| Exposure: | Full sun to part shade | Soil pH: | 5.0-8.0 |

| Spacing: | 10-15 feet | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Planting Depth: | 1/2 inch (seeds), depth of container (transplant) | Attracts: | Bees, butterflies, birds |

| Height: | 15 feet | Companion Planting: | Native sages, ceanothus, toyon, lemonade berry |

| Spread: | 10-15 feet | Uses: | Hedge, screen, ground cover, native plant garden, pollinator garden, slopes |

| Water Needs: | Low | Family: | Rhamnaceae |

| Time to Maturity: | 2-5 years | Genus: | Frangula |

| Common Pests and Diseases: | Aphids, whiteflies; scab | Species: | Californica |

Welcome Wildlife with a Water-Wise Plant

Growing a shrub like coffeeberry can give you some peace of mind to counterbalance the stress of fire season.

While offering some protection, these are also serene drought-tolerant ornamental plants connected to a larger ecosystem that benefits native insects and wildlife as development increases and wild spaces disappear.

It’s up to those who have the privilege to garden to incorporate native species into our landscapes, or better yet, to let them dominate our horticultural designs.

Have you grown coffeeberry from seed? Do you have an established plant in your garden that wild birds like to visit?

Who is your favorite feathered visitor? As a birder myself, I love hearing about which birds visit your growing space. Share your experiences with us in the comments below.

We must plant now for our future! If you found this guide helpful and inspiring, check out these articles next for more support in growing native plant species:

Hi Kat! I have a big Coffee Berry 8-10Ft. but it’s never had berries. I planted it roughly 10 yrs. ago and yes, I’m sure it’s a Coffee Berry. It gets a good amount of sun. It is in a row with Nine Bark and Mock Orange on either side of it. Any ideas?

Thanks!

Bonnie