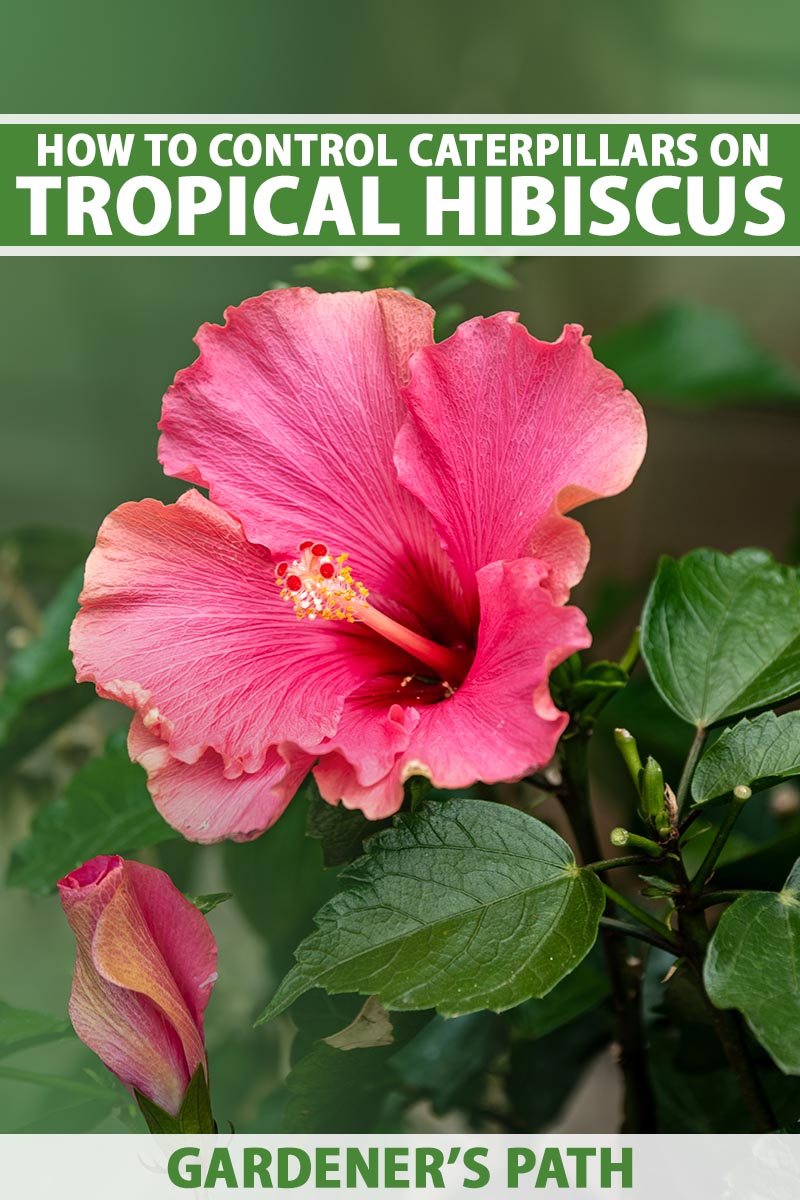

Keeping a tropical hibiscus healthy and safe from pests can be a challenge.

Whether this tropical beauty is included in your landscaping plans or you’re already growing one, there are a few specific pests that you should be on the lookout for in addition to the common garden culprits, depending on your location – and it’s not necessarily because of the damage they may cause to these semi-woody shrubs or small trees.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

Some can be a nuisance because of their ability to inflict a painful sting, which in some cases may require medical attention. Maybe bees or wasps come to mind, but in fact, the insect pests I’m referring to are caterpillars.

Like many garden specimens, tropical hibiscus plants may also suffer damage from aphids, scale insects, mealybugs, and whiteflies – you can learn more about these common pests in our guides.

In this guide, we’ll go over the caterpillars you need to be on the lookout for and discuss how to handle them if you find them, so they don’t become a bigger problem. Here’s the list of potential suspects:

Common Caterpillar Pests That Target Tropical Hibiscus

I’ve always been a fan of caterpillars because of the beautiful, beneficial moths and butterflies that they become.

When my kids were younger, we often collected the ones that become amazing adults, like hummingbird, luna, and polyphemus moths, as well as monarchs, so they could watch them form a cocoon or chrysalis and emerge.

A lot of kids – and pets! – enjoy the sometimes colorful, fluttery butterflies and moths, or wiggly, fuzzy larvae, and many are eager to pick up or touch them on sight.

We learned quickly to exercise caution in my family when we interacted with unknown caterpillar species because of a sting that one of our neighbors suffered – but up until then, I had no idea that caterpillars could sting!

After this, I taught my toddlers that some caterpillars are “fuzzy no-touches” and that helped them to understand to stay away.

Obviously, if you’ve got children, pets, or vulnerable adults in your home who don’t know this either, the presence of these insects can definitely become concerning.

Fortunately, knowing ahead of time what to expect and what these species look like can aid in identification to keep everyone safe – including your plants.

Common Caterpillar Pests That Target Tropical Hibiscus

As I mentioned, this list includes only the moths, caterpillars, and larvae that are often or exclusively found on tropical hibiscus species, cultivars, and hybrids.

Signs of damage from larvae can look like defoliation; shot holes through leaves or jagged, chewed margins; eggs typically deposited in clusters on the underside of leaves; and curled, dead, or dying leaves, sometimes with silky threads present.

Cocoons may also be visible in some instances.

It might be easy to dislike these larvae because of the danger they can pose, but it’s important to remember that they have no insidious intentions. Any insect that is capable of stinging does so only in self-defense.

If we steer clear, they won’t do us any harm.

Note that, outside the United States, other moth species are commonly found on hibiscus, such as Xanthodes transversa, aka the transverse or hibiscus caterpillar.

Most of these species don’t pose a serious risk to your plants, and the ones that do rarely cause enough damage to worry about. They will pupate and then fly or flutter off as adults soon enough.

If necessary, the best way to rid your shrub of a large infestation is to spray the foliage with a product containing Bacillus thuringiensis kurstaki (Btk), a beneficial bacterium that lives in the soil.

The advantage of using Btk is that it does not kill beneficial insects. However, it needs to be applied early in the pests’ life cycle to be effective.

Bonide’s Thuricide contains Btk and it’s available from Arbico Organics in quart- or gallon-sized ready-to-spray bottles, or as concentrate.

You can also use neem oil or insecticidal soap, but do so with caution to avoid dousing the blossoms. Both of these substances can also kill pollinators, so use them sparingly.

Bonide Neem Oil can be purchased in pint, quart, or gallon containers from Arbico Organics.

Monterey insecticidal Soap is also available from Arbico Organics in 32-ounce ready-to-spray bottles.

And, if you’d like to collect the larvae to observe their pupation and grand entrance as adults with wings, I recommend a mesh habitat such as this Pop-up Insect and Butterfly Habitat in a large, 24-inch size, available from Amazon.

Pop-up Insect and Butterfly Habitat

Just be sure to include a branch and some foliage for a food source.

For more information on general planting and caretaking for tropical hibiscus, see our complete growing guide.

1. Io Moth

The Io moth (Automeris io), also known as the peacock moth, is adorable by most people’s standards.

The yellow and brownish-pink coloration and two to-three-inch wingspan of the females of the species make them a favorite for those who enjoy finding and identifying lepidopteran insects.

I personally find them to be beautiful and fascinating, and you might soon agree with me.

This species belongs to the Saturniidae family, along with other well-known species such as the luna moth (Actias luna), polyphemus moth (Antheraea polyphemus), and atlas moth (Attacus atlas).

Both the brighter females and the darker males exhibit coloration known as a “startle feature,” which is a pattern of two blue and black circles on the underwings that resemble two open eyes.

This pattern is intended to deter predation – when the moth feels defensive, it’ll part its forewings to reveal these “eyes” to scare off potential predators.

Adults mate and lay eggs only once, in clusters on the undersides of leaves. These generally hatch between May and July. The eggs are under two millimeters in size and may be yellow or green, and exhibit a black dot on top.

Their natural range extends across the entire Eastern Seaboard of the United States, and into Canada and Mexico.

But this cute, fuzzy little moth produces larvae that are capable of delivering a painful sting in self-defense, if handled.

That sting leaves lingering pain and swelling when the fragile, hollow spines on the caterpillars’ back break off and become embedded in the skin.

The spines are concealed inside feathery protrusions which are connected to venomous glands. A sting can cause pain for as long as eight hours.

Caterpillars exhibit aposematic, or deterrent, coloration. They start off yellow and mature to bright green, with white or yellowish and brown or reddish-colored stripes along either side of their bodies.

As they grow, they molt and shed their previous skin, leaving a brown, shriveled remnant behind.

Adult moths have no functional mouth, so they don’t eat or cause any damage to plants, but the caterpillars can pack away quite a bit of material as they grow through several instars, or phases of molting.

When the caterpillars reach maturity, they weave papery cocoons in which to pupate, using dead leaves as camouflage. They’ll remain inside for one to three weeks in most cases, but in very arid regions or drought conditions, they may stay inside for over a year.

If you find one of these fellows defoliating your plants, you could try to relocate it while wearing gloves and using a spade or other garden tool to gently transport it without coming into direct contact.

If you’d like to allow them to complete their transformation into those adorable moths, however, you could let them stay put and warn others not to touch them.

2. Saddleback Moth

Next on our list of “look but don’t touch” creatures is the saddleback moth caterpillar, Acharia stimulea. This species belongs to the Limacodid family, also known as the slug moths.

This moth is an unextraordinary, small, brown specimen with folded wings that you might not even notice fluttering by. The caterpillar, however, is unmistakable, and if you accidentally touch one, probably unforgettable too.

These have a massive range, so you might see them anywhere along the Eastern Seaboard between New England and Florida, or as far west as western Texas northward to western Indiana. These little guys get around.

In warmer climates, light green, translucent eggs may be laid at any time of year. In temperate zones, they’re more likely to be found in spring and summer. This is a species that deposits eggs on the upper side of leaves.

The caterpillars have brown to black faces and rears broken by a large “saddle” of bright, lime green with a white-lined brown circle in the middle.

This aposematic coloration is designed to keep the larvae camouflaged under foliage and warn potential predators of danger.

Mature caterpillars only reach about three-quarters of an inch before they build their cocoons, so it’s easy to overlook them if they’re not out in the open.

It can be hard to tell if they’re coming or going because of the two fuzzy protrusions on their heads and rears.

Those protrusions, which resemble strange antennae, are covered in feathery spines that may look cute from a distance, but they can deliver a painful sting and a small dose of venom when broken.

Spines that break off under the skin will continue to cause irritation, and the venom injected into the skin can cause tissue damage and a sore, red rash. If you do happen to be stung by a caterpillar of this species, it’s best to promptly seek medical attention.

In fact, these are known specifically for their stinging capabilities rather than for any defoliation or damage they may cause to plants.

They’re also known for being a commonly chosen depository for beneficial braconid wasps, which lay their eggs on the backs of the larvae. The eggs hatch inside the caterpillar where they’ll parasitize and consume it.

Thick gloves and a garden tool might help you to safely lift the caterpillar for relocation elsewhere while avoiding contact.

Otherwise, leave it alone and let nature take its course if you’re not concerned that children or pets will be too curious to stay away.

3. Hibiscus Leaf Moth

While the presence of this caterpillar can be inconvenient due to its need to feed on foliage, the hibiscus leaf moth, Rusicada privata, is at least not venomous like the first two we covered.

This moth hasn’t received much attention among specialists to date, so there is little information about it available. We know that it’s rust to brown in color, just under an inch long, and mainly appears in the eastern part of the United States and some parts of Asia.

When their wings are folded, they tend to have an arrowhead-like shape, and they mainly mobilize in the evening. Their eggs hatch in late spring to early summer, and the larvae almost exclusively feed on hibiscus foliage.

You may see a curled leaf with silky threads holding it together when they’re present on plants. This encloses the pupa, which the moth will typically emerge from within one to three months.

Since they are not dangerous, these insects can be relocated by hand if found. It can be a little tricky to identify them because they can range in color from green to brown or almost black, but they have a yellow or orange spot behind their heads that might help.

If there are only a couple present, they can strip a few leaves but won’t kill your shrub, so they can be left in place.

Otherwise, you could relocate them in cases of a larger infestation, but since members of the mallow family are their primary food source, they may not survive.

4. Mallow or Hibiscus Sawfly

Last on our list is the mallow sawfly, Atomacera decepta. Rather than simply nibbling on leaves, this species, which is not a moth, tends to make shot-like holes in the leaves and can cause quite a bit of damage.

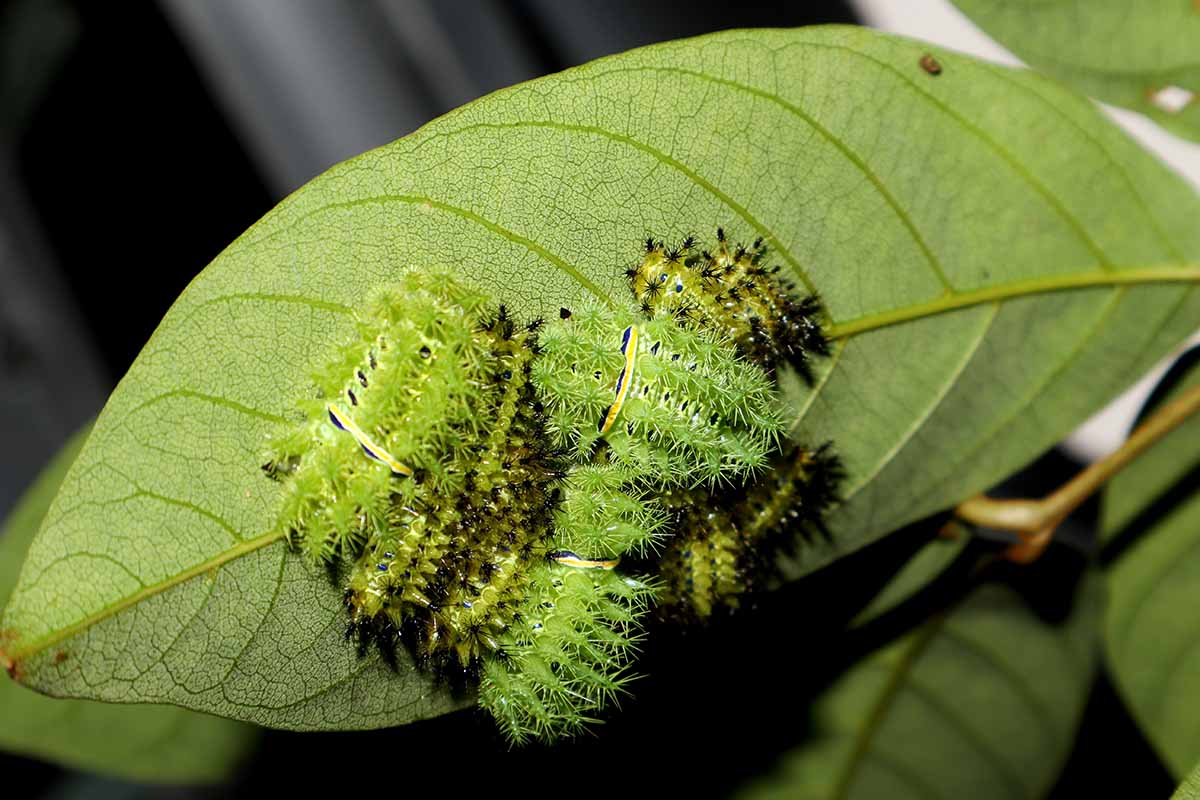

Unlike true caterpillars, the larvae of the sawfly have more legs and a wider head and thoracic section, so you can pretty easily tell the difference. The half-inch-long larvae are light green, and their heads are black.

Adult sawflies belong to the wasp family, and are generally under a half inch in length, so they’re tricky to spot.

They’re usually jet black, with a rust or orange V-shaped spot behind their heads, two small antennae, and flat, clear wings. They move quickly but they are not capable of stinging.

Adults lay eggs in the spring and the larvae hatch between May and October. Eggs are laid inside leaf tissue, so you may see a section of tiny, raised blisters on a leaf.

You can remove the leaf, press the eggs between your fingers, and discard it if you don’t want to deal with the larvae after they hatch out.

Once they hatch, several larvae tend to gang up on each leaf, chewing holes through it rather quickly. Sometimes the damage is severe enough to skeletonize leaves, which can lead to some die-off.

After the larvae have had their fill, they pupate in hard, rust-colored cocoons on the underside of leaves. They then hatch into adults that tend to stay with the same plant to continue the life cycle.

Unwelcome Guests, Unexpected Consequences

Don’t get caught heading to urgent care with a sting that could have been avoided. Keep an eye out for the species on this list that can cause injury and steer clear of them.

If they’re causing more damage to your tropical hibiscus than expected, such as in the case of a large infestation, turn to Btk, neem oil, or insecticidal soap, which are less harmful to the environment than harsh chemicals.

We’d love to know if you’ve spotted any of these caterpillars on your plants. Were you able to observe any emerging as adult moths? What other types of insects have you seen visiting your tropical hibiscus? Leave us some comments and share pictures below!

And, if you’re still looking for more information on growing hibiscus and mallows at home, check out these titles next:

I was surprised the other day to find this large 1 1/2 inch caterpillar. I asked for help from a native plants social media site and was rewarded with the name Rusicada privata – Hibiscus Leaf Caterpillar Moth. As it was found below a large Rose of Sharon, I believe this is an accurate identification. I live in coastal SE CT and have not seen this before. Thank you for the information.

See below for comments on this photo

Thanks for sharing your photo and details of the find, Jackie. We’re glad you were able to identify it!