Surprise, spring has come early!

Okay, I wish. But we can make it seem like spring is already here by forcing branches to bloom early indoors – even when it’s still the dead of winter outside.

Winter is undeniably a humdrum time of year for the flower lover in many regions. Sure, you can buy cut arrangements of greenhouse flowers to bring a little color indoors year-round, but what fun is that?

Outdoors, there is a world of color just waiting to burst forth. While it will happen naturally when spring arrives, we can hurry the process along.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

Just about any spring-flowering species can make a beautiful display for your home, so if you have access to any of the recommended trees and shrubs that we’ll cover here, you can make this process work for you.

Here’s what we’ll discuss to help make it happen:

What You’ll Learn

Ready for spring? Me too! Let’s get to forcing those blooms.

The Best Species to Force

Not all flowering trees and bushes can be forced to blossom indoors. While certain species just lend themselves to the process better than others, some species aren’t capable of being forced for one reason or another.

That said, if you have a woody bush or tree that sends out blossoms in the spring before it leafs out, you can try forcing it. Some might not work, but you aren’t really out much if the cuttings that you’ve taken don’t bloom, beyond a little time.

Some species are far easier to force than others, so we’re here to help give you a head-start in the planning department.

Broadly speaking, you can assume that flowering trees that later produce edible fruits or nuts will generally be the most difficult to force, and these will take the longest.

Ornamental flowering shrubs, on the other hand, tend to be the easiest and quickest, while fruit- or nut-producing shrubs fall somewhere in the middle.

Here are some recommended species to try out:

Almond

We’re not talking about the tree that is grown for its nuts here, but rather, the ornamental Prunus triloba var. multiplex.

If you’re lucky, you’ll see the beautiful pink flowers in just a few weeks, but it can take up to six weeks for cuttings to bloom indoors, so don’t lose hope if they don’t pop out right away.

By the way, you can force the edible almond species to bloom too, but it’s more difficult, and the blossoms are less showy. There’s nothing wrong with working with what you’ve got in the winter though, right?

Apple

Edible apples (Malus domestica) have petite blossoms that pop out in about three weeks. They’re moderately easy to force.

If you do your apple tree pruning in the late winter, you can use the trimmed branches for forcing. Waste not, want not!

Beech

You’re probably thinking this seems like a weird choice since beech trees (Fagus spp.) don’t produce your typical blossoms. But that doesn’t mean they aren’t beautiful.

Forced beech branches send out rosettes of green leaves that are just as pretty as any flower. And the foliage should start popping out in four weeks.

Birch

Like pussy willows, birches (Betula spp.) are worth forcing for their fuzzy catkins.

Paper birches (B. papyrifera) and silver birches (B. pendula) are particularly lovely. Depending on the species, the catkins can take about four weeks to emerge.

Buckeye

Ohio buckeyes (Aesculus glabra) produce white, pink, or cream blossoms on long panicles.

These will take about five weeks to force.

Cherry

You can force edible cherry trees (Prunus spp.), but ornamental cherries (P. campanulata, P. incisa, P. jamasakura, P. serrulata, P. sargentii, P. spachiana, and P. speciosa) have larger, fuller blossoms.

Either way, it will take about four weeks to see results.

Crabapple

Crabapples (Malus spp.) aren’t super easy to force, but the flowers are so pretty that it’s worth taking the chance.

These species take about four weeks to fully open.

Deutzia

Deutzia species produce beautiful clusters of pink and white blossoms.

They’re also easy to force and start blooming after about three weeks.

Dogwood

There are several dogwood species that have lovely flowers and all of them are easy to force, including Cornelian (Cornus mas), flowering (C. florida), and red-twig dogwood (C. sericea).

Red-twig and flowering dogwoods take five weeks to open, while Cornelian dogwood takes just two.

Learn more about dogwood here.

Fothergilla

Witch alders (Fothergilla gardenii) have frilly white blossoms that are extremely easy to encourage to open indoors.

You should see blossoms in about three weeks.

Forsythia

This is an iconic choice for forcing for a reason. Forsythia species force reliably, they’re one of the first to bud out in the spring, and the blossoms are striking with their intense yellow coloring.

Plus, it only takes one week to see the results of your work.

Honeysuckle

One of the easiest to force, with honeysuckles (Lonicera spp.), you’ll have blossoms in just three weeks.

Bush honeysuckle (L. tatarica) works better than vining species since you need to take woody growth, not green, pliable growth.

Horse Chestnut

The horse chestnut tree (Aesculus hippocastanum) is a bit more challenging to force, but the results are striking. Flowers are bright pink with reddish tones.

It takes at least five weeks to see blossoms, so plan ahead.

Lilac

Lovely lilacs (Syringa spp.) not only look good with their pretty purple blossoms, but they smell incredible. Start them in the late winter and in four weeks you’ll be enjoying the sensory experience.

Don’t be discouraged if the flowers don’t ever open fully. Sometimes the buds form and begin to open but stop before they open completely. They’ll still look pretty in a vase though.

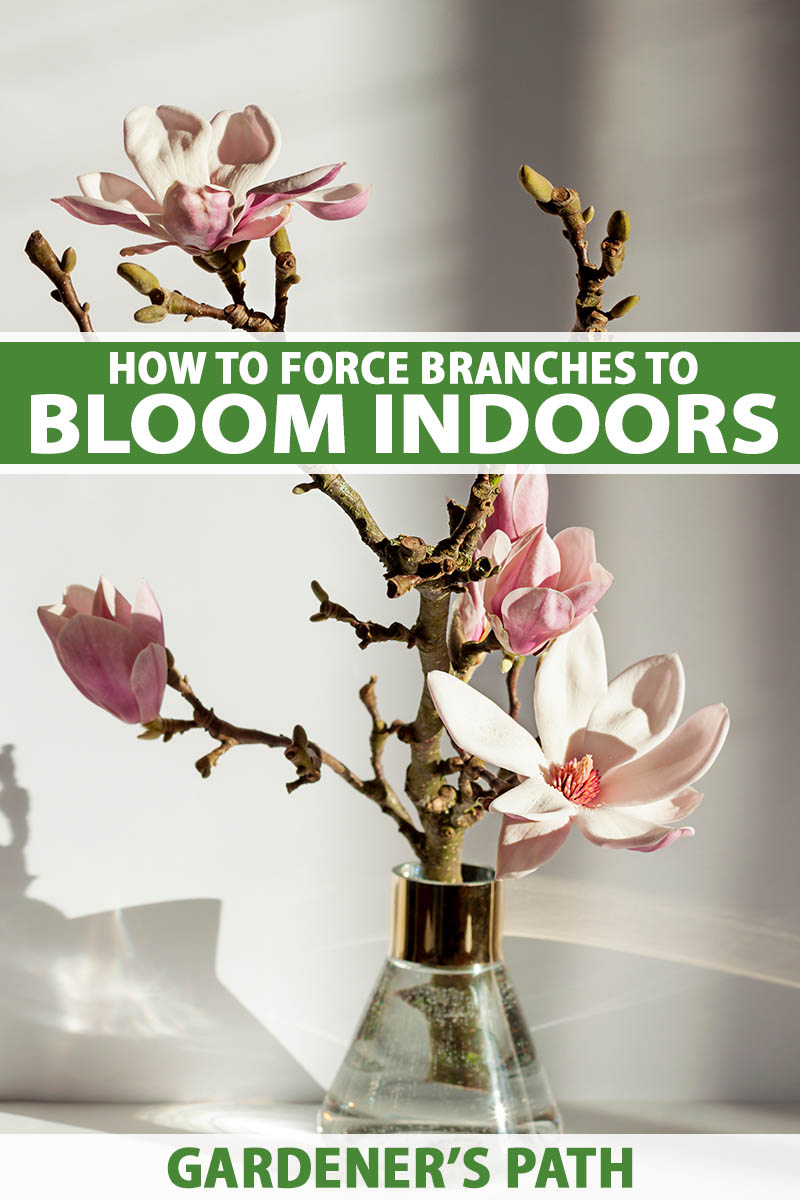

Magnolia

The magnolia tree (Magnolia spp.) isn’t quite as reliable as some of the shrubs on this list, but my goodness, it’s worth the effort.

After three weeks, if all goes well, the big, fragrant flowers should be fully open.

Maple

Technically you can force any maple species, but red maple (Acer rubrum) is the easiest and has the best flowers.

Flowers should open in about two weeks.

Pear

You can certainly force edible pears, but flowering pears (Pyrus calleryana) work best.

Flowers should open in about three weeks, but it can take longer.

Redbud

If you’re new to forcing branches, Cercis canadensis is an excellent species to start with. Two weeks and you’ll be drowning in pretty pink petals.

Other species work well, too, but they take a bit longer to emerge and can be a bit less reliable.

Find more info on redbud trees here.

Spicebush

Northern spicebush (Lindera benzoin) takes just two weeks to bloom and it is extremely easy to force the clusters of tiny yellow flowers to emerge.

Any species of spicebush can be forced, but common spicebush, as L. benzoin is also known, is the showiest and easiest to find.

Spirea

Spirea species feature dense clusters of white or pink flowers.

Blooms should take about four weeks to emerge.

Quince

Flowering quince trees (Chaenomeles spp.) take four weeks to open.

Any species works, but Japanese (C. japonica) works best.

Willow

Pussy willows (Salix spp.) don’t flower, but they send up little gray, furry catkins.

Any type of willow can be forced, so use whatever you have available nearby. These are easy and reliable species to force, with results in just two weeks, on average.

Find tips on growing willow trees here.

Wisteria

Wisteria species are stunning with their heavy, hanging clusters of flowers.

They take just three weeks to open.

Read more about wisteria care here.

Witch Hazel

Witch hazel (Hamamelis spp.) often grows wild, but you can find shrubs cultivated in yards or available to purchase at nurseries.

The distinct yellow, orange, or red flowers emerge in about three weeks.

Learn more about witch hazel care here.

When to Force Branches and Identifying Buds

As much as we may want to, you usually can’t start forcing branches in the early winter.

This is because most species need to experience a period of dormancy at a certain temperature to form buds. Temperatures usually need to be below freezing for around six weeks, though this can vary.

Magnolias, for instance, don’t need to experience a certain period of weather below freezing to bud, but fruit trees like apples and pears do.

You can try forcing branches as early as January in some regions and with some species, but most species will need to wait until February or even March. This, of course, varies according to region and species. For instance, forsythia might start sending out buds in January in one state, and February in another.

You don’t need to count back from the typical blossom opening time to determine when to start cutting branches.

In other words, if the species blooms in mid-April and takes four weeks to open, you don’t necessarily have to wait to take the cuttings until mid-March. Most species can actually be forced much earlier than that, so long as the buds are swelling.

The right time to force a plant is after the buds are starting to swell. Once they are, you can get to work.

So get out there, and take a look! The buds are usually shaped like teardrops, with some being pointier and more elongated, and others more thick and round. Leaf buds are usually more pointy while flower buds are more round, though this isn’t always the case.

Color isn’t a reliable indicator, since some young leaves emerge in shades of pink, yellow, or red rather than being green.

Not sure what you’re dealing with? Take a sharp knife and cut a bud in half.

If it’s a leaf bud, you’ll see little leafy bits inside. If it’s a flower bud, you’ll see itty-bitty flower parts, including petals, stamens, stigmas, filaments, and other parts.

Pussy willows will have a bit of tightly-packed gray fuzz inside, and species forced for their leaves will have tiny, distinct leaves that can be teased apart.

This is also a good way to tell if the plant is far along enough in the budding process to take a cutting. If you cut open a bud and don’t see any distinguishable parts inside, it’s too early.

Choose a day with weather that is above freezing to remove branches to bring indoors. Frozen branches are brittle, and they might crack or break rather than cutting away cleanly. This also eases the transition from outdoors to inside conditions.

By the way, if you head out into any public areas to cut your branches, be sure to check on the regulations governing the removal of plant material first.

How to Cut Branches

When choosing branches to bring inside, look for ones that are about as thick around as a chopstick, and that are long and straight. You can also pick branches that have a curved shape if that’s the look you’re going for.

While you can make an interesting display using branches that are all the same length, displays with pieces of varying lengths usually look better because they’re more dynamic and visually appealing.

Don’t choose broken or diseased-looking branches, and make sure each section you choose has visible swollen buds.

Be sure to also consider the shape of the plant you’re leaving behind. If you run outside in a snowstorm and blindly snip off a bunch of branches from one side of a shrub, you’re going to end up with a pretty lopsided display come spring.

You shouldn’t take cuttings from branches that were trimmed in the previous year either. That’s because most species form the best buds on the previous year’s growth, or something older.

To take a cutting, use a sharp, clean pair of clippers or secateurs and cut just above a bud or joint. You should take pieces that are at least 12 inches in length.

Immediately place the branches in warm water, or bring the cuttings inside and cut them again just before placing them in water.

You don’t want the ends to seal up or callus over, preventing them from taking up water. Instead, you want to put branches with freshly cut ends directly in the water.

Make each cut at an angle so the bottom doesn’t sit flush against the base of the container, which can also block water uptake.

You can also bruise the cut ends by crushing them slightly with a hammer. This is more useful for wood that is brittle or dense, such as lilac wood. Alternatively, you can cut a quarter-inch-deep cross in the base to improve water uptake.

You should remove any buds that are going to be sitting under the water. You can usually just rub these off, but larger ones might need to be sliced off with a sharp knife.

How to Force Branches

Place the cuttings in a vase, pitcher, or other tall container filled with lukewarm water. The branches should be submerged by at least a quarter, but no more than a third.

To avoid fungi or bacterial growth, add a teaspoon of bleach per gallon of water. You should also change the water every few days.

Do not place the container in direct sun. The light exposure should be indirect but bright. A location next to a window covered with a sheer curtain is ideal.

Temperatures should be around 60 to 70°F throughout the day and night, in order to produce flowers.

Winter air inside the home can be dry, so it helps to mist the branches once or twice a day.

If you don’t see any of the buds starting to increase in size or opening up slightly after two weeks, this is an indication that something went wrong. Try cutting a few more branches and start again.

Also, note that the closer a species is to opening naturally outdoors, the faster the buds should open indoors.

Troubleshooting Problems

If your buds don’t open, something obviously didn’t go as it should. Don’t let yourself become frustrated, because it happens to even the most experienced bud forcer.

While you can always try again, you want to know what you did wrong so you don’t make the same mistake the next time, right?

Having said that, it can be hard to tell exactly what went wrong unless there are obvious symptoms, such as fungus forming on the branches.

Common problems include cutting too early, disease pathogens such as fungi or bacteria in the water, too much sun or heat exposure, or cut ends that developed a seal before you put them in water.

Make sure you don’t take any cuttings until the buds have formed and are starting to swell. Remember, you can cut one open to see what’s happening inside.

Change the water frequently and put a small amount of bleach in to help prevent bacteria and fungi from infecting your cutting. A tablespoon per gallon of water will do.

Keep the cuttings out of direct sun and away from heat vents.

Finally, make sure you put each cutting straight into warm water, or make a fresh cut once you bring the cuttings inside and are ready to put them in water.

Maintaining Your Blossoms

Once the blossoms, leaves, or catkins have opened, temperatures should be kept somewhere between 50 and 70°F.

Cooler temperatures will help to extend bloom times. If you have room in your refrigerator, you can even place the flowering branches upright in a vase of water in the fridge overnight or at other times when they are not being displayed. This is an excellent way to keep cut flowers that are fully opened fresh for longer periods.

Keep the branches in cold water and feel free to add a splash of vodka or a floral preservative to the water instead of bleach to help extend the life of the blossoms. Either way, stop adding bleach in the water once the blossoms have opened.

Don’t place the container in direct sunlight, and try to keep it in a cool area, if possible. Remember, the cooler the temps are, the longer the blossoms will last.

Mist the blossoms once or twice a day to extend their life and keep them looking fresh longer.

Change the water every few days, and add fresh vodka or flower preservative each time.

It’s Time to Bring Spring Early

If you’re like me, you become antsy for some color and greenery once winter has really settled in.

After the holidays are over and I know there are still months of winter to go, I start craving some garden joy. That’s when I get excited to head outside and check to see if any of my trees or shrubs are ready for forcing.

What kind of species do you plan to force? Feel free to tell us in the comments below. Pictures are always welcome too!

Looking for a little more early spring color? Read some of our other guides next, starting with these: