Magnolia spp.

There’s a lot to love about spring, but arguably no other tree marks the coming sunny days of late spring like magnolias.

They’re one of the first trees to offer up a floral display, and if you pair them with another early bloomer like redbuds or flowering cherries, your yard can be a riot of color long before the rest of the world comes to life.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

Unlike some of the other early-blooming trees, certain magnolias can have a repeat flush of blossoms in the late summer. They’re the gift that keeps on giving! Others wait until spring is underway to put forth their flowers.

Some are even evergreen and give your space some much-needed greenery when most of the other plants around them are tucked in for a long winter’s nap.

I distinctly remember the first time I saw a magnolia tree. The giant flowers, thick petals, and dream-like colors made me certain the tree was fake. I asked my mom why she didn’t have any fake trees in our yard, since she had plenty of artificial greenery indoors.

I still look closely at magnolias when I walk by them because I’m not entirely convinced that those picture-perfect blossoms on a fully covered tree aren’t somehow all a mirage. They just look too good to be real.

Admittedly, when I inhale the intense fragrance, take a nibble on the pickled petals, or use a few branches to liven up my interior, the illusion becomes a bit more real for me.

Whether you want to add magnolias to your garden or just learn how to care for some existing trees, we’re going to cover the following to help you fully understand these prehistoric plants:

What You’ll Learn

Caring for magnolias isn’t all that difficult, but they do require a little bit of extra love if you want them to look their best.

Part of that is knowing when it’s the right time to plant feed, and prune them.

Don’t worry, we’ve got you. Let’s sort out what you should know!

Cultivation and History

Magnolias are trees and shrubs in the Magnolia genus. Since the 1990s, biologists have been able to use DNA to help them determine how to classify the plants, so their classifications have been shifting around a bit from their historical organization.

Lately, scientists have settled on a few subgenera: Magnolia, Yulania, and Gynopodium, with 12 sections and 13 subsections. All told, there are over 240 species.

Typically, magnolias grow in USDA Hardiness Zones 6 to 10, but you can find some that will grow outside of these regions.

If you don’t mind the limited selection, you can grow magnolias in every state in the US, all the way down to Zone 3 and up to the more tropical areas in Zones 11 and 12.

We’re talking Alaska to Hawaii. But those in Zones 6 to 10 will have a much broader range of options.

These eye-catching trees and shrubs are also fairly adaptable to different soil conditions, so long as the soil is well-draining. Ideally, the pH can range anywhere from 7.4 to 8.4. But slightly outside of that range is fine as long as it’s neutral to alkaline.

Like ferns, magnolias are one of those plants that we consider truly ancient. They were around long before humans, when dinosaurs were browsing around for nibbles.

They were among the first flowering plants, around even before bees were buzzing around.

We know from fossil records that magnolias have been on Earth for over 100 million years.

They used to be found pretty much everywhere across Asia, Europe, and North and South America. Now, they only grow indigenously in China, Japan, and North and South America.

On top of being around through some pretty exciting parts of the Earth’s prehistoric development, magnolias have been a part of human history for a long, long while.

In China, we know the magnolia has been cultivated since at least 600 AD because there are records of them in Buddhist temple gardens.

The flower buds have been in use even longer in Chinese medicine, with evidence that M. biondii, M. denudata, and M. liliflora were all part of traditional Chinese medicine from 2,000 years ago.

The first recorded mention of the magnolia in Western history was among the Aztecs in the 1400s, who called the tree Eloxochitl, specifically the deciduous species M. dealbata.

Magnolia flowers don’t have true petals. We’ll refer to them as petals in this guide because that’s the most familiar way of talking about them, but they’re actually tepals.

This is the term used when the outer parts of the blossom are undifferentiated, so they can’t easily be classified as either petals or sepals.

By the way, sepals are the plant part that typically protects the petal. So in other words, tepals are like an all-in-one petal and sepal.

Magnolia Tree Propagation

Whether you (or a generous neighbor) have a tree that you love and want to make more of, or you’re buying an exciting new cultivar, there are many ways to add more magnolia goodness to your yard.

Planting seeds, taking cuttings, air layering, or buying a young plant are all viable options.

From Seed

After those characteristic flowers fade, magnolia trees form large, cone-like fruits called follicles.

When the follicles open up, you’ll find a bunch of (usually) red seeds covered in a hard shell with a waxy skin.

Collect these seeds and put them in water for 48 hours to soften up the shell.

Once that shell has softened up a little to reveal its soft insides, grab each one and squeeze the end. Aim the other end of the pod toward a bowl because that inner seed is going to shoot out like a bullet.

Once you’ve shot out as many seeds as you need, place them on a paper towel or cotton cloth and let them dry out for 48 hours.

Now it’s time to stratify. Put the seeds in moist sand or vermiculite and seal them in a jar or bag. Place the container in the refrigerator for at least three months or up to four months. Keep the medium moist.

Once the seeds germinate and the radicle emerges, plant them directly outdoors. After four months have passed, even if the radicle hasn’t emerged, you need to plant.

Alternatively, if you live somewhere where the temperatures will be below 39°F for at least three months, you can plant them directly outdoors in the soil in the fall and skip the stratifying step.

Regardless of whether you do it in the spring or fall, when you plant the seeds, find an area with the right sun exposure and then prep the soil.

You want to prepare the area so that the seedling has the ideal growing conditions for the first few years.

As the tree matures, it will outgrow any of your early efforts to amend the soil, but you can give your tree the right start by providing it with loose, rich, well-draining soil.

Work in lots of well-rotted compost to improve both clay and sandy soil.

Plant the seeds no deeper than an inch and keep the soil moist as the seedling emerges from the soil and grows.

Once the tree is about a foot tall, you can relax a little and let the top inch or two of soil dry out between watering.

Remember that not all magnolia seeds will grow true. Hybrids may be sterile, or the resulting plant might be totally different from the parent.

Read more about growing from seed here.

From Cuttings

Softwood cuttings take well and this is a reliable way to reproduce a magnolia you love, since seeds won’t always grow true.

In the spring, as new growth is emerging on the tree, take a six- to nine-inch cutting of soft, green growth. Take twice as many cuttings as you think you’ll need because you never know what will happen. If you’re hoping to propagate one new tree, take two cuttings.

Stick the cut ends in a jar of water as you work so the cuttings don’t dry out.

Fill one six-inch pot for each cutting that you want to grow and fill it with four parts potting mix combined with one part rice hulls.

If you’ve never used rice hulls before, they are a sustainable alternative to vermiculite or perlite, and help soil retain water as well as improving drainage.

Arbico Organics carries quarter, half, or one cubic foot bags if you’d like to grab some for your propagating and growing adventures.

Take a pencil or chopstick and poke a hole in the medium in the center of each pot. Then, take a cutting and strip all the leaves from the bottom half. Cut the bottom of the cutting at a 45 degree angle and dip the end in rooting hormone.

Insert the cutting into the hole you made so that about two or three inches of stem is buried in the medium. Firm the medium up around it.

Water the medium well so that it’s moist (not soggy!) and place the cuttings in an area with bright, indirect light.

Place a cloche or clear plastic bag over the cutting. You might need to prop it up with a chopstick or stick or something because you don’t want the plastic to touch the cutting. Maintain moisture.

Over the next few months, the cutting will begin to develop roots.

You can tell because new leaves will form and if you give the cutting a gentle tug, it won’t come out of the soil. At that point, move it to a spot in direct sunlight for about four hours per day, and remove the plastic.

Continue to keep the soil moist until it’s ready to transplant a few weeks before the first predicted frost date in the fall or after the last predicted frost date in the spring.

A week before you intend to plant, harden the young trees off by taking them outside and placing them in the area where you will eventually plant them for one hour. Then, bring them back inside.

The next day, take them out for two hours before bringing them back in. Add an hour each day for the next five days.

Transplanting Saplings

Hundreds of thousands of magnolia babies are sold by nurseries every year. Chances are, if magnolias can grow in your area, you’ll find them at your local nursery.

Deciduous types should be planted in the fall or winter in mild climates when they’re dormant. Evergreen types should be planted in the spring.

Once you bring your new addition home, size up the root ball or container and dig a hole twice as wide and just a touch deeper.

Unwrap the roots or remove the tree from the pot. If necessary, brush off the soil to expose just the top of the roots. Gently loosen any roots that are tangled or twisted up.

Place the tree in the hole you made so that the roots you exposed at the top are sitting slightly above the soil line and fill in around the roots with soil. You want about 10 percent of the rootball to be above the soil line.

Water well and allow the soil to settle a little. You’ll probably need to add a bit more soil as it settles.

Apply a thin layer of shredded hardwood bark mulch over the roots for protection.

Via Air Layering

I love air layering. You get to grow a new tree without the risk of seeds not germinating or cuttings failing. Worst case scenario, you’ll just have to unwrap your air layering and try again.

Do this in the spring after the blooms have started to fade. Slice into some hard wood – not young, green wood – using a clean knife to remove the top layer of the bark.

You want a branch that’s at least as thick as a pencil. You should cut through the bark and cambium, and about an inch in length.

Dip a cotton swab in rooting hormone and wipe it onto the wound. Moisten some sphagnum moss and wrap a two-inch-thick layer of it around the cut and all the way around the branch.

Wrap clear plastic around the moss and seal both ends with rubber bands, twist ties, or electrical tape. Every week or so, crack open the plastic and make sure the moss is moist. Mist with water if it isn’t.

After a few weeks, you should start to see some roots growing in the moss. Once you do, go ahead and cut off the branch just below the layering. Remove the plastic, loosen up the roots, and trim off as much of the stem below the roots as you can.

Plant in the soil as you would a sapling.

How to Grow Magnolia Trees

In my opinion, the first consideration when planting anything should be the light exposure.

You’ll never be able to grow a sun lover in heavy shade, but you can always adjust the soil or moisture to adapt to your particular species.

With that in mind, for most species, full sunlight or partial sun is best. Basically, if you can give your magnolia at least four hours or so of direct light, you’re in good shape.

Of course, it depends on what species you’re growing, but most are pretty adaptable and if you live somewhere hot and dry, they’ll even appreciate some shade.

I’ll confess, I grew one magnolia in full shade. It didn’t start that way, but as the trees around it matured, it swiftly became darker and darker where it was growing. Eventually, it was exposed to about an hour of direct-ish sunlight each day.

While it was pretty leggy, it still bloomed every year. I had to support it with a complex system of ropes to keep it in a shape I liked, because it kept wanting to reach for the sun, but it was still blossoming and filling out with foliage despite my poor planning.

If you live somewhere hot and dry, a little shade will be welcome. If you’re somewhere cool and moist, full sun is totally fine.

Once the plant is established, it can tolerate a wide range of soil moisture, as well. Magnolias can even tolerate some drought once established.

Having said that, they do best in moist but well-draining soil. Generally, the plants need about three gallons of water per week for each inch of trunk diameter.

If you live in a dry climate, you might need to add a bit more, while those in cool climates might need to reduce this amount.

An easy way to tell what your trees need is to use a soil moisture meter or stick your finger in the soil. If it feels like a well-wrung-out sponge, it’s good. You don’t want it any wetter than that.

An established tree can handle drying out in the top few inches of soil between watering, but young trees should stay moist.

Magnolias have fairly brittle branches, and the flowers can also be ravaged by heavy winds, so you want to plant them somewhere protected from strong winds.

Starting just after the blossoms fade, begin fertilizing once per month until fall with a 10-10-10 NPK liquid fertilizer. Water it into the soil following the manufacturer’s directions.

Something like Covington Liquid Fertilizer is just right because it has the right balance of nutrients and comes in large enough containers that you can treat your tree multiple times.

Amazon carries 32-ounce containers of concentrate.

Growing Tips

- Plant in full or partial sun.

- Protect from wind.

- Soil should remain moist, though mature trees can tolerate some drought.

- Fertilize monthly during the late spring and summer.

Pruning and Maintenance

In general, you should avoid pruning unless absolutely necessary. The older a magnolia tree gets, the less it will tolerate any pruning.

When necessary, you should prune your magnolia trees to provide shape, remove dead or diseased parts, and to correct poor growth.

Evergreen types should be pruned in spring after flowering, and deciduous types should be pruned in early fall. Pruning at the right time helps lessen the amount of bleeding.

Prune out any vertical water spouts back to the main branch. Water spouts are vigorously growing, upright branches that emerge from the dormant nodes on branches.

You should also get rid of any broken or damaged branches. Feel free to prune a bit to improve the shape by taking off branches that look out of balance and any clusters of crossing, rubbing branches.

If the tree needs a lot of work due to neglect, do it gradually over several years. No need to rush the process.

Refresh mulch every year in the spring and heap on a bit of extra to protect the roots in the fall.

Depending on the species, a late frost can kill your flowers. So if you have a small shrub or tree, toss some frost cloth over the plant if an unexpected late frost is in the forecast.

Magnolia Cultivars to Select

There are hundreds of magnolia cultivars. Basically, if you can imagine it, someone has probably bred it.

We have a guide to the most popular and reliable options for the home gardener (coming soon!), so give that a look if you want to learn even more about the different species, hybrids, and cultivars.

Another excellent way to make your selection is to head to a local nursery. I’m not talking about one of those big box stores.

Those stores usually carry a few well-known names suitable to a wide range of climates rather than ones that are ideally suited to your area.

A local nursery will likely have some insight into which magnolias will do best in your region and they’ll probably carry several. They might even have tips to share on the ideal time to plant and early care for your specific region.

Star (M. stellata), saucer (M. x soulangeana), southern (M. grandiflora), and sweetbay (M. virginiana) are the most popular species in North America.

Having said that, there are a few cultivars that have withstood the test of time and that you can find just about anywhere. They’re adaptable, reliable options that are suitable for a large range of USDA Hardiness Zones.

‘Royal Star’ is a M. stellata cultivar that’s hardy in Zones 4 to 9.

It has a naturally oval-shaped growth habit with a height of about 20 feet. It flowers a few weeks after the typical star magnolia and lasts a bit longer.

The blooms are where this magnolia really stands out. They’re large and pure white with a star-like shape. The overall effect is of a tree covered in star-like fireworks celebrating the arrival of spring.

I think this one is a stellar option for anyone looking to give their first magnolia a try. Start the festivities by grabbing a two- to three-foot tree at Fast Growing Trees.

‘Ann’ is a hybrid developed by the National Arboretum with four-inch, bright reddish-purple and white, chalice-shaped blossoms.

It blooms a few weeks later than many other types, which means it avoids surprise late frosts that can destroy an early floral display.

More of a shrub, it won’t grow taller than 12 feet and has a pleasant round shape. Bring home #1, #3 multi-stem, or #5 multi-stem containers from Nature Hills Nursery.

Some magnolias have a dedicated following thanks to their solid reputations. Good old evergreen ‘D.D. Blanchard’ is one of them.

It’s a tall southern cultivar, growing up to 70 feet, with a columnar shape at just 30 feet wide. It’s hardy in Zones 7 to 9, so only the lucky gardeners in these areas can enjoy it.

Starting in mid-spring and through early summer, the tree is covered in large, cup-shaped, pure white blossoms made up of thick petals. It’s the classic southern magnolia.

If you like using magnolias for cut flowers, you’d be hard-pressed to find a better option.

Just picture a few three-foot branches in a clear vase showing off the rust and green leaves topped with the picture-perfect blossoms at the tip.

Nab one for your garden (and home display) at Nature Hills Nursery. They carry #3 containers.

As an aside, if you’re interested in eating the flowers at all, the color of the blossoms gives you a general indication of the flavor.

All magnolia flowers have a slight ginger-cardamom flavor, though it can be strong in some flowers and downright mild in others.

Lighter-colored petals tend to be milder and darker ones tend to be stronger.

Managing Pests and Disease

Some people complain that magnolias are prone to problems. Others find them to be downright tough, hardly ever requiring any help.

The reality is that if you’re growing your magnolia tree in the ideal environment, you’re unlikely to experience problems.

But the more you try to shoehorn a tree into the wrong environment, the more likely you are to encounter pests and diseases, and the more likely they are to damage your plant.

That’s often true of any plant, but it’s especially true with magnolias. They’re adaptable and strong, but they can only be pushed so far.

Regardless of whether your plant is in the perfect spot or one that’s a bit more challenging, here are the most common pests and problems you might run into:

Herbivores

For the most part, it’s the birds that will be drawn to your magnolias. They’re a favorite of our winged friends. But ungulates might occasionally present a problem.

Deer and Elk

Despite what you may have heard, ungulates will eat magnolias. They’ll snack on the petals, leaves, and soft, young wood. I’ve seen it with my own eyes.

But they don’t often cause serious damage, and mature trees are pretty much impervious.

You’ll sometimes see these trees sold as deer resistant because deer and elk won’t pick them over other things. But they will take a bite.

If you worry about deer eating your young trees or even breaking those tender branches, check out or guide on how to protect your garden from deer.

Insects

Like we said, if your plant is in the right environment for the species and it’s kept generally healthy, pests aren’t likely to be a problem.

If they are, they usually won’t do much damage. But that doesn’t mean you can just sit back and relax. You’ll want to be aware of the following:

Aphids

Aphids are sap-sucking insects that use their sucking mouthparts to feed on trees and plants.

They’re a common pest on all kinds of different plants and they seem to be especially fond of magnolias. At least, they are in my neck of the woods.

They’ll rarely cause serious problems for your plant, though they can spread disease and the honeydew that they leave behind can make sitting in the shade of your tree a sticky, unpleasant experience.

If you’ve never dealt with aphids before, our guide can walk you through the process of identifying and eradicating these pests.

Scale

Like aphids, scale are another common problem on all kinds of different plants.

They’re sometimes mistaken for a disease rather than a pest because they can be flat or fuzzy, resembling fungus or bumps on the bark of the tree.

And like aphids, they use their sucking mouthparts to feed on the sap from the tree.

There are many species of scale that feed on magnolias, including cottony cushion (Icerya purchasi), calico (Eulecanium cerasorum), magnolia (Neolecanium cornuparvum), tulip tree (Toumeyella liriodendron), false oleander (Pseudaulacapis cockerelli), and Japanese maple scale (Lopholeucaspis japonica).

It doesn’t really matter which species is eating your tree. They all cause weakness and defoliation. And they can also spread disease.

Check out our guide to managing scale to figure out what to do about them.

Insecticides don’t work very well, and there aren’t a ton of predators that can puncture their waxy protective coating, so it takes some effort to eradicate them. But there are things you can do.

Yellow Poplar Weevils

East of the Rockies, yellow poplar weevils, also known as magnolia leafminers (Odontopus calceatus), are a common pest.

The small, black beetles hide out in leaf litter under the trees before emerging in spring to lay eggs on the undersides of the tree’s leaves.

After they hatch in mid-spring, the larvae feed on the leaves and buds of magnolias, and while this might sound like a largely cosmetic issue, a large infestation can cause misshapen growth, defoliation, and weakened trees, making them prone to breakage and collapse.

Of course, this kind of damage is more common in young trees, but it can happen in older, well-established trees as well.

The good news is, this pest has lots of natural enemies. Parasitoid wasp species including Catolaccus hunteri, Habrocytus piercei, Horismenus fraternus, Zagrammosoma multilineatum, and Scambus hispae will all harm the beetles and larvae, either through feeding or parasitic activity.

A healthy garden will usually have lots of these helpful friends, and if you don’t, it’s often a sign that you need to work on your biodiversity and soil health.

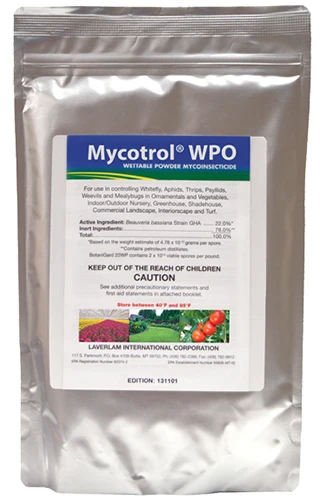

You don’t have to rely on beneficial insects alone, though. A product that contains the fungus Beauveria bassiana will kill the larvae.

Mycotrol WPO is packed full of these spores for effective pest control. It comes in one-pound bags filled with powder that you mix with water and use as a spray on your infested magnolias.

If you don’t already have this handy worm and grub killer around, grab some at Arbico Organics.

Disease

There are a lot of diseases that can potentially impact magnolias, but only a few that are relatively common.

Bacterial leaf scorch, canker diseases, and leaf spot are potential problems, but these are the ones to really watch for:

Crown Gall

Caused by the bacteria Agrobacterium tumefaciens, crown gall causes masses to grow at the base of the plant just above the soil. These galls can be quite large and unsightly.

Anything that can cause an opening in the bark, from insect feeding to nicking your tree with an edger, can allow the bacteria to sneak in. Prevention is your best route because the available treatment options aren’t fantastic.

Try to be careful not to damage the bark, keep pests away, and go over any new plants to look for galls before you introduce them into your garden.

When you see galls forming, you might be able to cut out the growth. Otherwise, you’ll need to pull the tree and solarize the soil to sterilize it or you risk spreading the bacteria to other plants in your garden.

Powdery Mildew

Similar to the disease that you’ll commonly see on squash and melons, powdery mildew causes matte white patches on both sides of magnolia leaves. It’s caused by the fungus Erysiphe magnifica and is becoming increasingly common.

As the season progresses, the leaves will begin to drop from the trees. Eventually, by late summer, trees can be entirely defoliated.

If you catch it early, you can clip off any infected leaves and dispose of them in the garbage (not the compost). You should also do a little pruning to improve air circulation.

Rake up any leaves in the fall to prevent the fungus from overwintering and re-infecting the plant in the following year.

Finally, spray the tree with neem oil once every two weeks as long as symptoms are present.

Neem oil is one of those things that you should keep around because it’s so useful for lots of things, including controlling common pests and various diseases.

If you don’t have some already, pick up some neem oil from Bonide. It’s available from Arbico Organics in a quart- or gallon-size ready-to-use spray, or pints of concentrate.

Wetwood

If you grow elms, poplars, or magnolias, at some point, you’ll probably bump up against wetwood.

It’s a bacterial infection caused by pathogens in the Clostridium, Bacillus, Enterobacter, Klebsiella, and Pseudomona genera.

Typically, it hides away inside the tree until a buildup of gasses forces liquid outside of the tree, where you can see and smell it. This oozing liquid can attract flies, beetles, and other insects.

Wetwood, also called slime flux, probably won’t kill a tree, but it will cause its health and vigor to weaken over time, leaving it susceptible to other problems. If you can prune off the infected area, go for it.

Otherwise, just support your tree with the care described in this guide and it can still live a good, long time.

Wood Rot

Wood rot is just a general term for several diseases that can cause the wood to rot. It’s typically caused by fungi or bacteria.

There are several types that can cause problems: white rot results in soft, spongy tissue, brown rot causes dry, flaky tissue, and soft rot causes the material to break down.

If you see mushrooms growing on your tree, that’s often a sign that rot is happening. Armillaria mellea, as well as species of Ganoderma, Pleurotus, and Trametes are all common fungi to watch for.

If you have any sort of rot without oozing liquid showing on the tree, or branches breaking off with a soft center, you have wood rot.

Wood rot is most common in older trees, and it often seriously impacts the tree. One that is seriously rotting is weak and becomes dangerous because it can fall over at any time.

Treatment varies depending on the fungus, but most of the time, once you see symptoms, it’s best to remove the tree.

Best Uses for Magnolia Trees

Depending on whether you’re growing a shrub, dwarf, or massive tree, these plants can be used in a variety of ways. You can find teeny-tiny bonsai magnolias, massive shade trees, and everything in between.

Evergreen shrubs can be hedges or living fences, dwarf trees are marvelous in containers, and some of the smaller species are the perfect anchor for the rest of your garden.

Magnolias are closely related to buttercups, so I like to make a cheeky little nod to the relationship and plant buttercups around my trees.

If you want to use the flowers in food, you have even more options. As a general rule, white flowers are more citrusy and floral and generally mild.

Pink petals have the classic ginger-cardamom flavor. Darker colors tend to be more bitter and strong.

I went on a bit of a taste-testing journey recently, and I found that Loebners (M. x loebneri) usually had the most classic, pleasant flavor. Kewensis magnolias (M. x kewensis) were mild and tasted like orange and ginger.

I also found that every Southern magnolia I tried had a mild but interesting flavor ranging from mild lemon to spicy orange. All of them had an undercurrent of citrus.

And it’s not just the petals that are edible. The inner follicles are also edible. Pickle them or chop them up and use them as you would petals.

All magnolia species are edible, but you should always test a small amount before diving all the way in to ensure that you don’t have an allergy or sensitivity.

I think pickled magnolia petals are incredible. Pickling releases the ginger flavor and reduces the bitterness.

To make your own, fill a pint jar with washed, unpacked petals. Fill the rest of the jar with rice wine vinegar or apple cider vinegar, two tablespoons of sugar, and two teaspoons of salt.

Screw on the lid and gently agitate the jar. Let it sit in the refrigerator, agitating daily for a week.

At that point, it’s ready to eat straight out of the jar or, better yet, as a topping for salads, sandwiches, and crostini.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Evergreen and deciduous trees and shrubs | Flower/Foliage Color: | Pink, purple, white, yellow /green |

| Native to: | North and South America, Japan, China | Maintenance: | Moderate |

| Hardiness (USDA Zones): | 3-12 | Tolerance | Some drought when established, some shade |

| Bloom Time: | Spring, summer | Soil Type: | Loose, rich |

| Exposure: | Full to partial sun | Soil pH: | 7.4-8.4 |

| Time to Maturity: | Up to 30 years, depending on species | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Spacing: | 5-20 feet, depending on species | Attracts: | Birds, bees, butterflies |

| Planting Depth: | 10 percent of root ball above soil (saplings), 1 inch (seeds) | Companion Planting: | Bluebells, buttercups, daffodils, ferns, hellebores, hostas, periwinkle |

| Height: | Up to 120 feet | Avoid Planting With: | Plants that need dry soil and full sun |

| Spread: | Up to 40 feet | Family: | Magnoliaceae |

| Growth Rate: | Slow | Genus: | Magnolia |

| Water Needs: | Moderate | Species: | Gynopodium, Magnolia, Yulania |

| Common Pests and Diseases: | Aphids, deer, elk, scale, yellow poplar weevils; crown mold, powdery mildew, wetwood, wood rot | Varieties: | Acuminata, ashei, denudata, figo, grandiflora, kobus, liliiflora, loebneri, macrophylla, salicifolia, sargentiana, soulangeana, stellata, virginiana |

We’re Mad for Magnificent Magnolias

Whether yours is a petite shrub or a towering tree, whether it pops out first thing in spring or saves its display for a little later, the one thing they all have in common is that magnolias are magnificent.

They’re unlike anything else out there. Perhaps the biggest challenge in growing them is stopping at just one or two.

I can’t wait to hear about your magnolia journey. Did you inherit one with a new home? Are you bringing a baby back from the nursery? Where will you be growing it? Share with us in the comments.

Of course, magnolias can’t carry all the weight in a garden. Well, they’re so commanding that maybe they can!

But still, you’ll probably want a few other ornamental landscape trees to add to the mix, right? If so, consider checking out the following guides:

Hi Kristine, I knew you through the “Hydrangeas Podcast”. As you can notice I am new in this chapter of gardening.

My problem now is a Magnolia I have just planted 10 days ago and it has started to present different problems that I can’t identify – see the pics – can you give me some indications on what to do. Please.

As I mention with the Hydrangeas, I live 40 miles North of Houston, TX, and we must have a lot of mildew.

Hi Miguel, please could you try uploading your pictures again, they have not shown up here and I’m not able to retrieve them. Thanks!

I have had three magnolias in my yard for years and in the spring they have always leafed out at the same time, speed, and size. This year one is doing what they’ve always done, the middle one is growing at a smaller rate, speed and size-leaf wise, and the third is doing the same slow growth, only even slower, but the top half of the third tree is still not leafing out. I’m at a loss as to what is happening. Any ideas? Help? Information?

Hi Laura, I’d be happy to help, but the symptoms that you describe could be caused by a number of things. How is your soil drainage and moisture? Have you had a particularly wet, cold, or dry winter? What is the sun exposure like on each of the trees? Do you see any signs of insect or disease if you examine the trees closely? Things like a sticky coating on the leaves, fuzzy growth, lumps or bumps on the stem? Also, feel free to send some images along with more details and that could help me narrow down the issue.

Ms. Lofgren, thank you so much for your website and posts. They are fantastic to read! I inherited a Magnolia Ann that I am still learning how to care for. I am in zone 9 and as of this day am finding success with growth considering a lot of sun over 100 degrees as of late. I have one plant growing from a cutting and several growing from seedlings. It’s July in zone 9, should I plant them in the location I wish for the largest one to grow or wait until fall as it appears to suggest? I am… Read more »

Hi Ricardo, I’m so glad to hear that our guides are useful for you! I would wait for the fall to transplant. Moving plants during the heat really stresses them, and while they might be fine, the risk of shock or even death is higher than during cooler times of the year. It sounds like you have a fantastic set-up and the potting medium sounds great for your needs. My biggest piece of advice is to listen to the plants. If they look happy and are growing, you’re doing things right, and it sounds like you’re nailing it!