Wisteria spp.

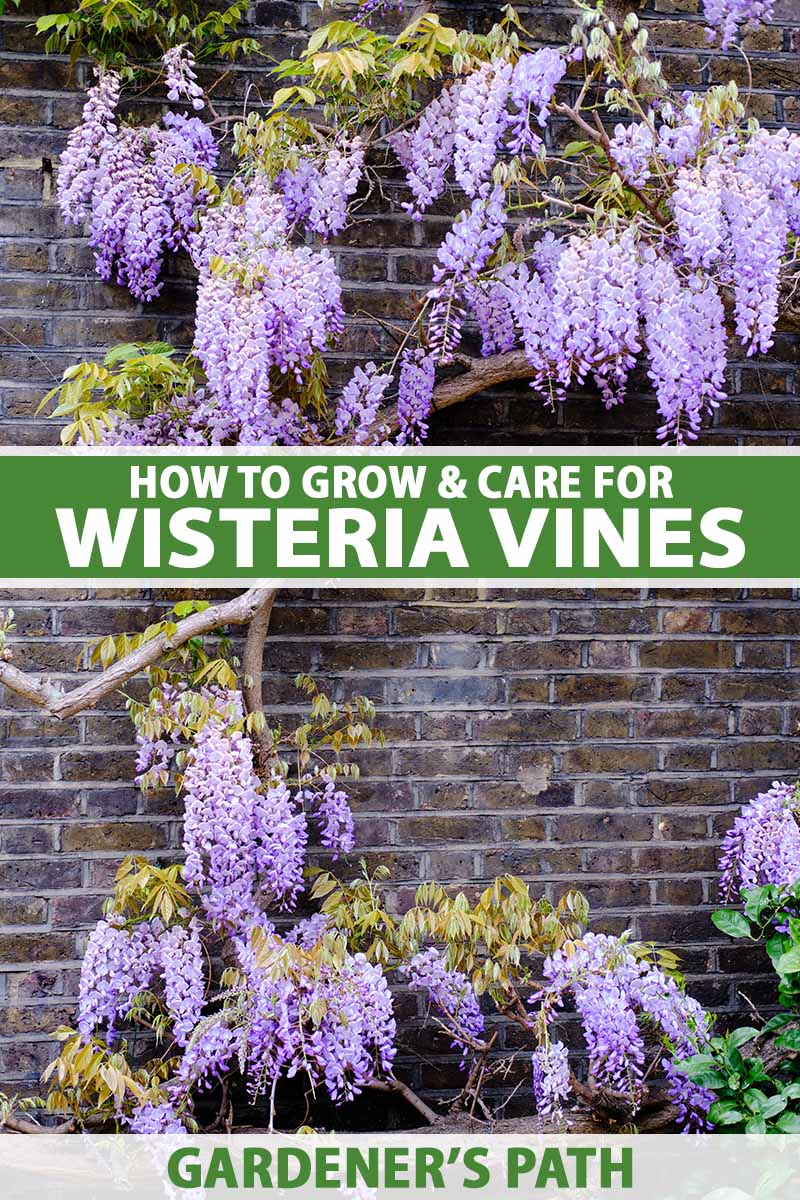

Can we talk about wisteria for a minute? I mean, a vine in full bloom is like something straight out of a fairy tale.

The long, vibrant clusters of blossoms and the ancient-looking wood draping across an arbor or old wall make it pretty impossible not to feel impressed.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

I bet even if it was a total pain in the rear to raise that people would still be making a go at it. It’s not challenging at all, though. In fact, it might be a little too easy.

So easy that it sometimes grows where we don’t want it.

But these days, we have less invasive options available that still look every bit as striking, and they’re just as simple to plant and raise.

If you want to help yours look its best (without it taking over the planet), let’s dive into the wild and wonderful world of wisteria. Here’s what you can expect in this guide:

What You’ll Learn

Growing wisteria is sometimes more of a matter of figuring out how to keep it under control rather than encouraging it to grow.

Don’t worry, we’ll go over that, too. Here we go!

Cultivation and History

There are four common species of wisteria that you’ll find in home gardens.

These are American (W. frutescens) Kentucky (W. macrostachya), Chinese (W. sinensis), and Japanese (W. floribunda).

The different species can all look extremely similar, with pinnate leaves, long panicles of blossoms, and woody stems that can each grow up to 25 feet long.

Those clusters of blossoms are called racemes, and they can be up to 24 inches long in colors like white, pink, blue, and a variety of purple hues.

After the flowers fade, seed pods form. These pods can help you determine whether you have an Asian species, which have hairy pods, or an American species, which have smooth pods.

Asian types also bloom when the plant is bare whereas American types bloom after the plants have leafed out.

Be aware that though they’re stunning and easy to fall in love with, they can be invasive.

Plus, you might think that a vine will look lovely growing up a column on your patio, but over the years, the trunk can become so massive that it will topple the support it’s growing on.

And wisteria vines growing up trees are likely to eventually smother and kill them.

Wisteria Propagation

Before you can start enjoying the view, you need to put your plants in the ground.

Most people opt to buy a little plant at a nursery, and this is definitely the quickest and easiest way to go. But you can also propagate seeds, use air layering, or take cuttings from existing plants.

Whichever method you choose, once you’re ready to transplant in the ground, prepare the soil well by working in lots of well-rotted compost at least a foot deep and two feet wide.

From Seed

Propagating from seed is an exercise in patience. It might be 15 years before you’ll see flowers.

But part of the joy of gardening is being able to nurture a plant from a dry seed to a massive, thriving specimen.

Keep in mind that if you harvest your own seeds, you can’t be sure what you’ll get. Many hybrids don’t grow true or they may be sterile.

You can either buy seeds or pluck them off your existing plants. If you go the latter route, wait until the pods have turned brown and dry. At that point, you can snip them off the plant and cut them open to reveal the seeds.

To cut them, think of a pea pod. You want to make a slit down that seam without cutting all the way through and potentially damaging the seeds inside.

Store the seeds until the following spring. You’ll sow them a few weeks before the last predicted frost date.

Whether purchased or harvested yourself, when it’s planting time, soak them in warm water for 24 hours. The water will cool over time, but don’t worry about warming it back up.

After 24 hours, pull out the seeds and nick them with a metal file or nail clippers to break through that hard outer coating.

Sow the seeds an inch deep and at least 10 feet apart in prepared soil, moisten the soil, and keep it moist until the plants have become well established.

From Cuttings

Propagating seeds takes a long time, and you can’t always be sure of what you will get.

Cuttings, on the other hand, mature faster, and you can accurately reproduce the parent plant with this type of cloning.

To take a cutting, wait until the plant has stopped blooming and take a six-inch piece of soft, new growth. Remove all of the foliage from the bottom half of the cutting and dip the cut end in a rooting hormone.

Place the cutting in moist potting soil in a container that’s at least five inches across. Tent a plastic bag over the cutting to help preserve moisture. Place the cutting in bright, indirect light and keep the soil moist.

Once new growth has started emerging, you’ll know that roots have started growing underground. Wait until at least four new leaves have formed before removing the tent.

Keep the plant watered and give it a few hours of direct light each day until fall rolls around.

Now you can harden the plant off by taking it outside to a sunny but protected area for an hour.

Take it back inside and do the same thing the next day, adding an hour. Do this for a week and your rooted cutting will be ready to transplant.

Make sure to put the plant in the ground a few weeks before the first predicted frost date in your region.

Air Layering

Before you head outside to start your work, grab yourself some clear plastic to wrap around the layering, some moist sphagnum moss, a sharp knife, and some twist ties, electrical tape, or twine to seal the package.

You also want to have some opaque white plastic like a plastic shopping bag.

After the flowers are finished, find a mature branch at least as thick as a pencil and clear away the leaves from a six-inch section.

At one of the leaf nodes where a leaf was growing, peel away some bark to expose the inner green cambium layer.

You might need to use a sharp knife to make a slice in the outer layer to release a piece that is about a half-inch wide and two inches long.

Sometimes I’m able to just peel the bark if there’s a loose bit I can get my fingernails around, but sometimes it takes some careful cutting.

Spray some water and sprinkle a little rooting hormone onto the exposed bit.

Now, wrap the sphagnum moss around the branch. You want it to be about two inches thick. Cover it in plastic wrap and seal the ends.

Cover the whole package with opaque plastic. This protects the moss from drying out or overheating.

Your job now is to check the moss every week or so and make sure it’s still moist. If it starts to dry out, get in there with a spray bottle and wet it.

Eventually – we’re talking four or five months later – you’ll start to see roots growing in the moss. It’s time to be excited!

In the fall, cut the branch away from the parent plant just below the root growth and remove all of the moss. Transplant in the ground as you would a purchased plant.

Transplanting Purchased Plants

Purchased plants will become established more quickly than those propagated using any of the other methods mentioned here, so if you’re in a hurry, there’s no better way.

Dig a hole twice as wide and as deep as the pot that the plant is growing in.

Grab your plant and remove it from the pot. Wisterias aren’t huge fans of being transplanted, so do it carefully and try not to disturb the roots.

Place the plant in the ground and fill in around it with soil. You want the root ball to sit as deep as it was in the container.

Firm up the soil and water it in. If the soil settles, add a bit more.

If you’re planting multiple vines, place them 10 feet apart.

How to Grow Wisteria Vines

Chinese wisteria will tolerate shade better than other species, and it might even require shade in hot, southern climates.

Other species and hybrids should be planted in full sun. In too much shade wisteria plants will absolutely not bloom – they’re temperamental that way.

It’s particularly important to keep the soil moist when the plants are blooming and to avoid letting the soil become too dry when the flower buds are forming.

Otherwise, the vines can handle some drought. The goal should be to add moisture whenever you stick your finger into the soil and it feels dry up to your second knuckle.

Add water at the soil level. Don’t water on the leaves, or you risk inviting disease.

Wisteria is a true vine, and it will climb up anything it’s close to.

If you place a trellis against a wall, it will eventually snake behind the trellis and pull it from the wall. It will sneak into your roof, rip apart a wood fence, or weigh down a plastic arbor.

I’m telling you, this stuff needs a strong support structure and one that you don’t mind getting a little beat up.

Don’t plant wisteria against your house unless you’re willing to do the work to keep it under control. It can lift up your roof shingles, clog your rain gutters, and sneak behind window trim.

Don’t have the right situation? Train it as a tree.

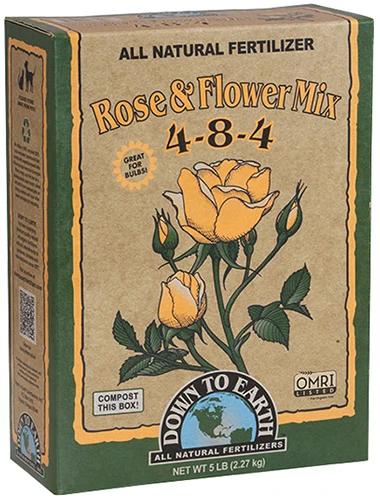

Wisteria fixes nitrogen in the soil, so you don’t want to use a high-nitrogen fertilizer. Look for a low-nitrogen, high-phosphorus fertilizer. Many flower-specific fertilizers have this formulation.

For instance, Down to Earth’s Rose & Flower Mix is low in nitrogen and potassium and high in phosphorus. It’s perfect for wisteria plants and, yes, roses.

Down to Earth Rose & Flower Mix

Snag some at Arbico Organics in one-, five-, or 15-pound biodegradable boxes.

If your plant isn’t blooming well, you might want to increase the phosphorus if you live in an area that is typically deficient.

When the pH is too high, it can cause iron chlorosis, so try to maintain a slightly acidic to neutral soil pH between 6.0 and 7.0.

Chlorosis caused by an iron deficiency makes leaves turn pale green or yellow between the green veins. This weakens the plant, but it’s a simple fix if you correct the pH.

Not sure if your soil is acidic or alkaline? Check the pH with a soil test.

Growing Tips

- Water when the top two inches of soil has dried out.

- Most species need full sun.

- Provide sturdy support if you grow wisteria as a climber.

Pruning and Maintenance

Pruning is one of the keys to growing beautiful wisteria. Do it wrong, and you’ll be disappointed. Do it right, and you’ll be treated to a stunning display.

Blooms are produced on new growth, so if you prune in the spring, you run the risk of ruining that year’s show.

Pruning also helps keep an over-exuberant plant under control, helps light reach the interior of the plant so it doesn’t become sparse, and keeps everything looking nice and tidy.

Pruning should be done in both summer after the blossoms are gone, and in winter when the plant is completely dormant and has no foliage.

Summer pruning is done with the goal of tidying the plant up and opening up the exterior to allow light in. Prune off some of the newer exterior growth back to the main branch it’s growing off of.

Prune back any excessively long offshoots, leaving two or three leaf buds. Make your cuts just in front of a leaf bud to encourage attractive branching.

You can prune all of the new growth back by about half to encourage bushier growth. Cut back any suckers that are within a foot of the ground.

If you don’t remove some of this new growth, the plant will become overgrown with foliage rather than blossoms.

In the winter, remove any dead, diseased, or damaged branches. Then, provide the plant some shape, taking off any oddly shaped or strangely growing branches. Prune back the branches that you pruned in the summer a few more inches.

An established wisteria almost can’t be over-pruned. I’ve literally chopped them off at the ground level, and the plant sent new shoots up from the roots that I hadn’t pulled out. That’s partly what makes them capable of being invasive.

Of course, you don’t want to prune hard unless you have a truly unruly plant.

Try not to remove more than half of the plant at a time to preserve its health, and even less for more recently established vines.

Training should be done as the new, soft growth emerges.

You can allow the plant to do its thing in terms of where it grows, but if you want to guide it, you can tape or tie down new growth where you want it to go.

Just be sure to remove each tie as the branch it’s holding starts to expand and harden.

Wisteria Cultivars to Select

If you live in an area of North America where wisteria tends to become invasive, you should choose an American species or cultivar.

Not only is there less risk of a native plant becoming invasive, but these bloom more readily and easily.

In the past, American species weren’t as popular because the panicles are smaller, but new cultivars are every bit as showy as their Asian counterparts.

Here are some of the most popular options:

‘Betty Matthews’ is also known as Summer Cascade.

It can grow up to 20 feet long but, as a Kentucky species (W. macrostatchya) cultivar, it’s mild-mannered enough not to become invasive or tear apart your house.

It’s cold hardy down to Zone 4 and was less prone to freeze damage than other wisterias in trials.

It has showy racemes up to nine inches long with petals in hues of lavender, blue, and white.

Summer Cascade ‘Betty Matthews’

Nature Hills Nursery has bare root plants if this option sounds like something you’re looking for.

‘Blue Moon’ is another super hardy plant growing down to Zone 4.

It’s a Kentucky cultivar that features lavender-blue flowers on foot-long racemes on a 25-foot vine.

’Blue Moon’ is not content to bloom and be done, though. It will return for a second and third show in the spring and summer.

Bring the moon down to your earth by snagging a live plant in a quart, two-gallon, or two- to three-foot option at Fast Growing Trees.

For a change of pace, ‘Alba’ is a white cultivar with nine-inch-long racemes on a 15-foot-tall plant.

Don’t confuse the W. frutescens cultivar of this name with the W. floribunda one. The latter is much more aggressive and fast-growing.

Want More Options?

For a full guide to the many different exciting cultivars and hybrids, take a peek at our roundup, “17 of the Best Wisteria Varieties.”

Managing Pests and Disease

Deer and other herbivores won’t bug wisteria, but pests like aphids and scale will.

There are a few diseases that will pop by now and then, too. A well-pruned and properly placed vine is far less prone to problems than one that is stuck in less than ideal conditions.

Insects

The insects that feed on wisteria usually won’t destroy your plant. But they can cause unsightly damage and they spread disease. Here are the most common pests:

Aphids

Aphids are the most common pest on wisteria, and if you ignore the fact that they can spread diseases, they’re really not a big deal.

They might turn a few leaves yellow and make a bit of a mess with their honeydew excrement, but a mature vine can withstand them pretty well.

There are many species of aphids that will feed on wisteria, including green peach aphids (Myzus persicae) and rosy apple aphids (Dysaphis plantaginea).

Regardless of which kind is making itself home in your vines, they can all be tackled in the same way with some basic techniques, which we outline in our guide to managing aphid infestations.

Japanese Beetles

When you have an infestation of Japanese beetles (Popillia japonica), it’s easy to tell.

They chew through the leaves of plants, leaving holes in between the veins that can make the foliage look like lace. It might actually be kind of pretty if it wasn’t so annoying…

As with aphids, a mature vine won’t have any trouble withstanding an infestation.

But if they bother you or you have a young plant, visit our guide to Japanese beetle control to learn how to eliminate them.

Leaf Miners

Leaf miners are tiny worms in the Coleoptera, Diptera, Hymenoptera, and Lepidoptera orders.

They’ll chew little tunnels inside a leaf like they’re mining for gold, leaving strange maze-like discoloration on the outside.

If these tiny pests make themselves at home in the foliage of your plants, it’s not the end of the world. They won’t kill your wisteria.

Still, they can be challenging to deal with if you want them out of your yard.

If you’re facing a miner battle, read our guide for tips.

Disease

Wisteria isn’t typically prone to diseases. When one does occur, it usually won’t kill your plant.

It helps to be aware of what to look for so you can take any steps necessary to eliminate a problem. Watch for these:

Crown Gall

A lot of gardeners don’t realize that crown gall is a disease.

It looks like a funky growth, but it’s actually caused by the bacteria Agrobacterium tumefaciens rather than just a strange growth habit.

These growths are tumors caused by the bacteria and, I don’t know how to break this to you, but they’re really bad news.

The disease itself might not kill your wisteria, but it looks unattractive and reduces the plant’s vigor. You can prune the symptomatic stems off, but the bacteria is still in there, biding its time.

Look for lumpy growths on any of the above-ground wood.

There’s no known cure. It’s best to remove any plants that are infected because they can spread the bacteria to other plants, some of which might not be able to withstand an infection as well as wisteria does.

If you pull a plant, don’t put anything else there for the next two years.

Leaf Spot

If you notice yellow, white, or brown spotting on the foliage of your plant, it’s likely leaf spot.

Caused by the fungi Phyllosticta wisteriae and Septoria wisteriae, it’s not deadly and you don’t need to do anything to treat it except pruning off the infected areas.

Avoid leaf spot by keeping your plant well pruned and by watering at the soil level rather than on the leaves.

Best Uses for Wisteria Flowers

The woody vines of wisteria can be an extremely versatile option in the garden.

Obviously, they’re lovely as vining specimens climbing over a (sturdy!) trellis or other support. Or you can use them as a privacy hedge. I dare you to find me a traditional hedge that looks as beautiful as wisteria in bloom.

They make effective privacy barriers, and with the right planning, they can even help shade your windows from glaring afternoon sun.

While it takes a little extra work, you can also grow wisteria in the form of a tree.

To make it easy, just buy a premade tree and maintain the shape as it grows.

You can pick up a ready-made option at Fast Growing Trees. They have one- to two- or two- to three-foot options.

Fruit trees might be the traditional choice for espalier, but wisteria vines can be pretty incredible trained up a wall.

Just remember to be thoughtful about where you place yours and to maintain it well.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Flowering perennial vine | Flower/Foliage Color: | White, pink, purple/green |

| Native to: | Asia, North America | Maintenance: | High |

| Hardiness (USDA Zones): | 4-9 | Water Needs: | Moderate |

| Bloom Time/Season: | Spring, summer | Tolerance: | Drought |

| Exposure: | Full to partial sun | Soil Type: | Loamy |

| Time to Maturity: | Up to 15 years from seed | Soil pH: | 6.0-7.0 |

| Spacing: | 10 feet | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Planting Depth: | 1 inch (seeds), same depth as container (transplants) | Attracts: | Bees, birds, butterflies, hummingbirds, other pollinators |

| Height: | Up to 30 feet | Uses: | Specimen, climber, espalier, tree |

| Spread: | Up to 20 feet | Family: | Fabaceae |

| Growth Rate: | Moderate to fast | Genus: | Wisteria |

| Common Pests and Diseases: | Aphids, Japanese beetles, leaf miners; crown gall, leaf spot | Species: | Floribunda, frutescens, macrostachya, sinensis |

Make the Most of Wild, Wonderful Wisteria

Done right, there’s nothing like wisteria. You couldn’t dream up a more fantastical plant. It’s really unlike anything else.

Done wrong, it’s a real menace, smashing through fences and roof shingles like the Hulk.

But there’s no reason why you have to battle with your vine. With the right variety and the tips in this guide, I hope you’ve found your way to a harmonious garden.

How are you growing your wisteria? Are you training it as a tree? Looping it over an arbor? Fill us in on all the details in the comments section below.

If you’re looking for some more vines for your yard, check out the following guides next:

Hello,

I have two lovely Blue Moon wisterias on my patio. They are very healthy and beautiful, but the seed/pod dropping is intolerable. I have seeds sprouting everywhere, and boy are they tough to dig out once they get started! I am to the point of dispair, and plan to kill these two lovelies (while I tearfully apologize to them!) They are 7 years old, climbing on my patio covering15 feet wide each, blossom profusely and smell great! It pains me to think about doing them in, but the mess is unbearable. I wonder if I take one out, will the remaining one still blossom and produce pods? Or must I kill them both to be rid of the problem? They are in planters with other plants, and I cannot pull them out (it would take a tractor to do it!) or easily cut them. The trunks are wonderfully entwined around themselves, and quite a work of art. I would like to leave them in place, and perhaps poison them. (It hurts me to even say this!) I’m thinking of injecting roundup into the trunk. Any thoughts on how to commit this murder? I li