Homalodisca vitripennis

The glassy-winged sharpshooter, Homalodisca vitripennis, is native to the southeastern United States and northeastern Mexico.

It belongs to the Homalodisca or sharpshooter genus of the Cicadellidae or leafhopper family and is a “true bug” in the Hemiptera order.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

A sharpshooter is a large type of leafhopper, a winged, hopping pest.

A true bug has two distinctive qualities: they have mouthparts that puncture and suck, and they are hemimetabolous, or characterized by incomplete metamorphosis.

Instead of hatching as an adult, these insects go through one or more nymph stages called “instars” before maturity.

Read on for a discussion of the glassy-winged sharpshooter.

Discover why it poses a deadly threat to over 300 crops and ornamental specimens and learn to identify and address it in your growing space.

Here’s what we’ll cover:

What You’ll Learn

Let’s begin our discussion of this notorious pest.

What Is a Glassy-Winged Sharpshooter?

A glassy-winged sharpshooter, aka GWSS, is a sapsucker that feeds primarily on plant stems rich in xylem, sap-filled tissue that carries nutrients through the roots, stems, and leaves.

Feeding alone may cause wilting in young plants, but large flora may suffer no ill effects.

So why all the fuss?

As we said, when a sapsucker feeds, it punctures and sucks. The GWSS uses a tube-like proboscis to make a hole from which it extracts sap.

Unfortunately, when it does so, it may serve as a vector for deadly plant diseases, injecting bacterial pathogens that it harbors in its body known as Xylella fastidiosa into its unsuspecting victims.

GWSS breeds on approximately 100 different host plants, feeds on over 300 different plant species, and not only hops, but flies a distance of three to 16 feet.

It is a force to be reckoned with, infecting nursery plants sold in the commercial market, public plantings, and private landscapes like a botanical Typhoid Mary.

X. fastidiosa affects over 500 crops and ornamental plants, including: almond, avocado, bird of paradise, blueberry, brush holly, cherry, cottonwood, crape myrtle, eucalyptus, euonymus, hibiscus, peach, pittosporum, plum, lavender, macadamia, maple, oak, olive, pecan, rosemary, and sunflower.

Multiple strains cause incurable diseases including alfalfa dwarf disease, almond leaf scorch, Pierce’s disease in grapevines, citrus variegated chlorosis, and oleander leaf scorch.

GWSS has severely impacted commercial growers in California. In 1989, eggs were detected on nursery plants and X. fastidiosa has been wreaking havoc in vineyards since the 1990s.

Identification

Some leafhoppers are tiny, like the red and blue candy-striped Graphocephala coccinea, which measures about 3/10 of an inch long (6.7 to 8.4 millimeters).

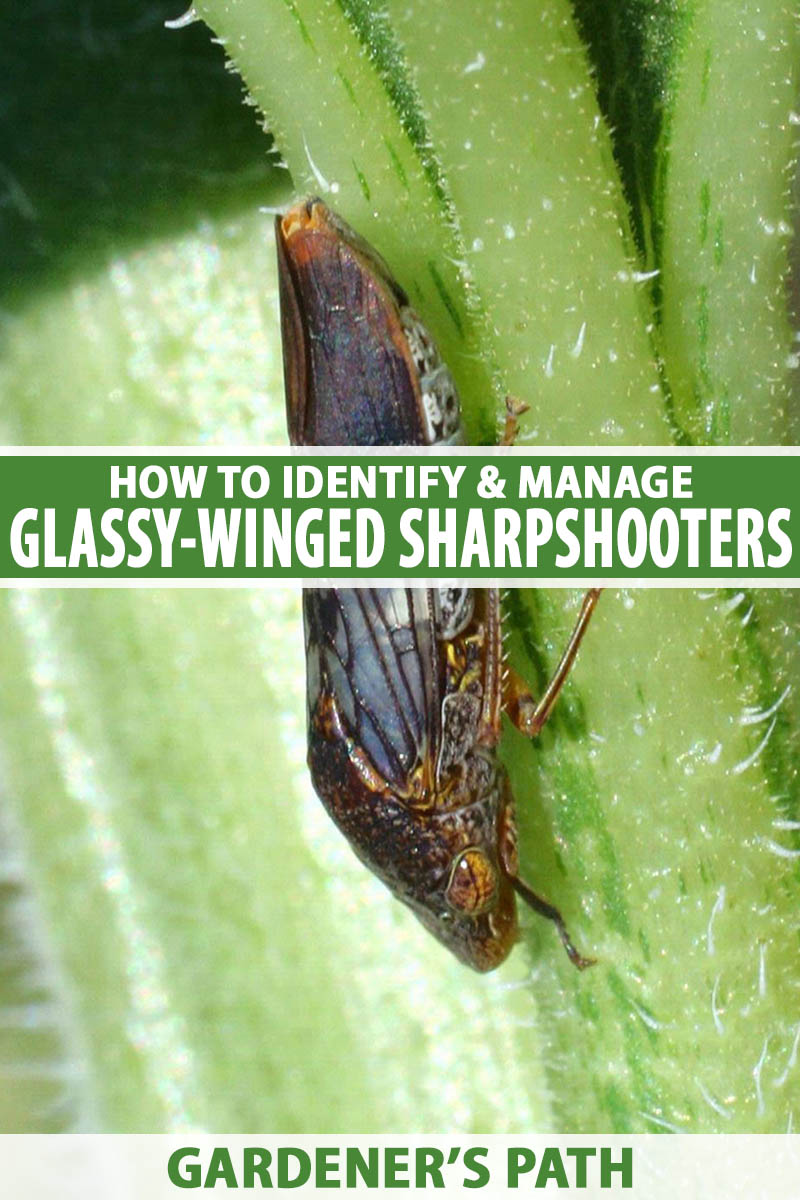

Sharpshooters, on the other hand, are large species. An adult GWSS measures half an inch (13 millimeters) from head to wingtip and is easier to see.

Adults of the species have brown to black bodies. There are cream to yellow spots on the head and back that help to distinguish it from other leafhoppers.

Adult wings range from clear and red-veined to clear with no veining, fading with age.

Females may have chalk-like white spots on their backs.

Nymphs resemble adults and range from one-tenth of an inch to approximately half an inch long. They have bulging gray eyes and blotchy green-gray bodies and may be wingless or winged.

Biology and Life Cycle

Following mating in the spring and summer, females lay between one and 27 eggs on the undersides of leaves.

They look like a green blister and are covered in white secretions called brochosomes. They turn brown before hatching, leaving telltale scars in the foliage where the nymphs are born.

Newborn nymphs feed on tender main stems and leaf stems or petioles. They grow wings as they mature.

GWSS adults and nymphs consume 100 to 300 times their dry body weight in xylem juices daily and excrete large quantities of liquid called “leafhopper rain.”

As it evaporates, the excreta leaves a whitewash-like residue wherever it has been deposited. You may even notice it on your car.

There are generally two generations of GWSS per year.

Adults winter over in wooded areas, citrus trees, ornamental plants, and weeds, slowing their activity to partial or “incomplete” hibernation and re-emerging the following spring.

Organic Control Methods

While GWSS feeding may not cause extensive damage, the transmission of disease-causing bacteria will likely destroy both crops and ornamental species.

The following environmentally-friendly control methods can help you avoid and manage this pest in your landscape.

Cultural

Cultural controls are of no use once the pests are in your locale. However, there are preventative measures you can take, such as:

Avoiding planting crops and ornamental species that are known to attract GWSS.

Clearing your growing area of known host plants that harbor overwintering pests, like fruit trees and weeds.

Inspecting new plants before purchase. Look for eggs and nymphs, report findings to the nursery staff, and do not purchase affected merchandise.

When selecting new trees, shrubs, herbaceous ornamentals, and edibles, choosing X. fastidiosa-resistant varieties.

Physical

Preventative physical controls such as the following may prove effective as avoidance measures and early-infestation actions:

Cultivate crops beneath floating row covers.

Inspect leaf undersides and remove and destroy those with whitish masses containing greenish eggs.

Introduce flowering insectary plants, like coriander, dill, and fennel, that attract beneficial insects like parasitic wasps.

Place netting over dwarf fruit trees and crops like blueberries.

Biological

Biological control methods use predators of GWSS to control their populations. Examples include:

Introducing co-evolved natural predators to the landscape that recognize GWSS as food.

Examples are parasitic wasps in the Cosmocomoidea genus, including C. ashmeadi, C. fasciatus, C. morrilli, C. morgani, C. triguttatus, and C. walkerjonesi. These “parasitoids” lay eggs among those of GWSS and do not prey upon beneficial insects.

Other beneficial GWSS predators are assassin bugs, lacewings, praying mantises, and spiders.

Following the latest developments involving the use of entomopathogenic fungi, like P. formicarum and M. anisopliae, that can destroy GWSS.

Monitoring the progress of a new chimeric protein treatment making headlines in the grape industry that would allow commercial growers to avoid using chemicals and removing affected plants.

Staying tuned for further study on whether or not mimicking the vibrational mating sounds of competitive males can disrupt mating and reduce insect populations.

Organic Pesticides

While the diseases spread via GWSS feeding are incurable, it may be possible to reduce a pest population with a non-chemical approach. You might:

Apply a pyrethrin-containing product, like Pyganic, to the foliage and stems. This natural pesticide is derived from chrysanthemums.

It paralyzes the nervous system of adults and nymphs. Find it at Arbico Organics.

Treat plants with horticultural oil or neem oil, a natural pesticide made from neem tree seeds, which impair the breathing and feeding of adults and nymphs.

Apply a product containing acetamiprid to the foliage. It kills adults and nymphs and prevents hatching. This organic pesticide targets sapsuckers and blocks the spread of oleander leaf scorch.

Install yellow sticky cards without pheromones, attraction chemicals emitted during mating. GWSS does not give off these chemicals and is not drawn to them.

Hopping adults and nymphs that land and stick there no longer pose a threat, and traps can also be used to monitor populations.

Chemical Pesticide Control

There are chemical controls for GWSS, but contact is toxic to pets, people, and beneficial insects, negatively impacting biodiversity.

They are more likely to be the choice of commercial growers than the home gardener. The chief example is:

Treating the soil with systemic neonicotinoid chemicals, nicotine-like insecticides that poison pests’ nervous systems.

Two common ones are imidacloprid and thiamethoxam. They kill adults and nymphs, and when applied to the soil, can block oleander leaf scorch.

In some locations, the GWSS exhibits resistance to both chemicals, and the rotation of neonicotinoid products does nothing to inhibit the development of chemical pesticide resistance.

Steer Clear of the Sharpshooter

The glassy-winged sharpshooter poses a significant threat to hundreds of crops and ornamental species in southwestern regions of the United States.

Its sapsucking behavior can transfer bacterial X. fastidiosa to plants, putting them at risk for multiple incurable diseases.

Use caution in the home garden. Purchase plants from reputable purveyors.

Check for eggs on leaf undersides, “leafhopper rain,” and wilting young stems. Be vigilant and take immediate action to remove and dispose of affected foliage.

Proactive cultural practices and biological treatment methods are the first and often only lines of defense as the GWSS becomes increasingly resistant to neonicotinoid chemical insecticides.

This invasive pest is widespread in California, Hawaii, and the southwestern United States, where integrated pest management systems are in place to preserve commercial yields despite its ubiquitous presence.

We gardeners can report our experiences and eradication efforts to our local county extension offices to aid in monitoring populations and designing integrated pest management systems aimed at curbing the glassy-winged sharpshooter’s impact on growers in the field and at home.

Have you encountered glassy-winged sharpshooters? Let us know in the comments section below!

If you found this guide informative and would like to learn more about garden pest control, we recommend the following:

Hello, I am an amateur gardener. Don’t do much, but love plants and nature. Have a beautiful hibiscus tree in a planter that I brought in from outside for the winter last week. I live in Plano, Texas. So far, I have found five of these guys. Identified with a bug finder app with a photo. I have a mix of peppermint essential oil and water that I spray on them and they die. Hoping it won’t damage this beautiful plant. It’s about 7 feet tall and 4 feet wide. I just sprayed the plant lightly all over and on… Read more »

Hi Shani –

I understand your concern for your lovely hibiscus tree.

Moving the other plants away and inspecting daily are excellent proactive measures.

You can try any of the approaches recommended in the article.

My concern is that while the peppermint-water-tea tree oil mixture seems to be working, the danger lies in the potentially lethal plant diseases the sharpshooter can transmit to your hibiscus tree, neighboring indoor plants, and those outside in the yard.

My best advice is to contact your local agricultural extension to report the presence of the glassy-winged sharpshooter in your area and seek further advice.